Related insights

Explore related documents that you might be interested in.

Read Online

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank all the disabled children, parents and whānau, kaiako, service leaders, and others who shared their experiences, views, and insights through interviews, group discussions, and surveys. We thank you for giving your time, and for sharing your knowledge and experiences so openly and whole-heartedly.

We also thank the key academics, and staff from the Ministry of Education and New Zealand Teaching Council, who participated in interviews and for their support in delivering this evaluation.

We want to acknowledge and thank the members of the Expert Advisory Group who shared their knowledge and wisdom in guiding this evaluation. The members were:

- Frances Anderson, Senior Disability Rights Advisor, Human Rights Commission

- Professor Mere Berryman, ONZM, Waikato University

- Dr Taima Fagaloa

- Matt Frost, Principal Advisor, Lived Experience (on secondment to Whaikaha: Ministry of Disabled People)

- Kerry McBride, Service Manager, Ministry of Education

- Pauline Melham, Senior Advisor, Office for Disability Issues, Whaikaha

- Professor Missy Morton, University of Auckland

- Dr Tracy Rohan, Principal Advisor Learning Support, Ministry of Education Canterbury

- Dr Gill Rutherford, Otago University

- Lorna Sullivan, NZOM

- Frian Wadia, MNZM

We acknowledge and thank all the disabled children, parents and whānau, kaiako, service leaders, and others who shared their experiences, views, and insights through interviews, group discussions, and surveys. We thank you for giving your time, and for sharing your knowledge and experiences so openly and whole-heartedly.

We also thank the key academics, and staff from the Ministry of Education and New Zealand Teaching Council, who participated in interviews and for their support in delivering this evaluation.

We want to acknowledge and thank the members of the Expert Advisory Group who shared their knowledge and wisdom in guiding this evaluation. The members were:

- Frances Anderson, Senior Disability Rights Advisor, Human Rights Commission

- Professor Mere Berryman, ONZM, Waikato University

- Dr Taima Fagaloa

- Matt Frost, Principal Advisor, Lived Experience (on secondment to Whaikaha: Ministry of Disabled People)

- Kerry McBride, Service Manager, Ministry of Education

- Pauline Melham, Senior Advisor, Office for Disability Issues, Whaikaha

- Professor Missy Morton, University of Auckland

- Dr Tracy Rohan, Principal Advisor Learning Support, Ministry of Education Canterbury

- Dr Gill Rutherford, Otago University

- Lorna Sullivan, NZOM

- Frian Wadia, MNZM

Executive summary

Quality early childhood education (ECE) affects how well disabled children do at school and in life – from academic achievement and earning potential, to health and wellbeing.

The Education Review Office (ERO), in partnership with the Human Rights Commission (HRC) and the Office for Disability Issues (ODI), looked at how well the education system is supporting disabled children in early childhood education. We found that too many disabled children are excluded from ECE and, while many services provide safe and nurturing environments, we need to strengthen teaching practices. This report describes what we found and what is needed to significantly improve education for these priority learners.

Participation in high-quality ECE positively impacts a range of education and life outcomes including health, wellbeing, academic achievement, and earning potential. High‑quality ECE supports children to develop the social, emotional, communication, cognitive, and motor skills which enable them to thrive. A focused, intentional approach to developing these skills is particularly critical for disabled children as it sets the foundation for their future learning and engagement with others. Research shows that the greater the participation in ECE, the greater its impact.

Disabled children and young people have the same rights to enrol and receive education as other learners. To thrive, they need to be able to enrol in and access early childhood education, be fully included in all aspects, and have the curriculum adapted to their needs. Like all learners, they need to receive quality teaching, in supportive environments, and with strong partnerships between their kaiako and their parents and whānau.

This study looked at the quality and inclusiveness of education provision for disabled children in early childhood education. It answers four key questions:

- How well are disabled children doing?

- What is the quality and inclusiveness of education provision (including teaching practice)?

- How strong are the system enablers that support more inclusive and higher quality education?

- What key actions could lead to improved outcomes for disabled learners?

How well are disabled children doing?

Disabled children enjoy ECE, feel safe and that they belong. We found disabled children are participating and enjoying ECE. Most parents and whānau believe their child feels loved and cared for, and that they belong at their service.

Disabled children are being excluded from enrolling and fully participating. We found a significant number of parents and whānau are being discouraged from enrolling their disabled child, and are asked to keep their disabled child home for specific activities. Kaiako also lack confidence about including disabled children in some activities.

We do not know how well disabled children are progressing. We found many services lack information showing how well disabled children are progressing, and do not communicate children’s next steps with their parents and whānau.

Children with complex needs are doing less well. Children with complex needs experience exclusion more than their disabled peers with less complex needs. Kaiako are less likely to discuss children’s learning with their parents and whānau. Parents and whānau of children with complex needs are less likely to report their child feels safe and that they belong.

Which areas of education for disabled children could be strengthened?

We found many committed early childhood services, and a range of good practice in providing education and support for disabled children. But we also found four areas that could be strengthened.

- Kaiako are not confident teaching disabled children, and struggle to access support to help them develop. Kaiako confidence in teaching disabled children is low. A third of kaiako do not feel confident enough to deliver a curriculum that is inclusive of disabled children. Targeted professional learning and development, and experience supporting disabled children, improves kaiako confidence. Accessing development and capability-building support is an ongoing challenge.

- Partnerships with whānau need to be more focused on their child’s learning. Discussions with parents and whānau often focus on what has happened during the day rather than how learning is progressing. Parents and whānau are often not aware of how well their child is progressing. Only two-thirds of parents and whānau are satisfied with their involvement in developing and reviewing their child’s Individual Learning Plan (ILP), a critical component of a disabled child’s learning support.

- Services need to have a better understanding of how well disabled children are progressing, and how good their provision is. Many services do not have good information about how well they are providing for disabled children, and many lack focus on this important group. Forty-one percent of leaders reported provision for disabled children is rarely or never a focus of internal evaluation. We also found that service leaders are much more positive about the quality of provision for disabled children than parents/whānau or kaiako, further highlighting the lack of clarity on quality of provision.

- Transitions from ECE to schools are not working as well as entry into ECE. Transitions from ECE into school settings are not working well. Nearly a quarter of parents and whānau are not satisfied with how their child is supported when transitioning to school. Communication with and the sharing of information between ECEs, support services, and teachers is a challenge. The need to re-establish the case for their child’s need for support, and navigating the system, is also a challenge for parents and whānau.

Recommendations

Early childhood education is still not delivering for all disabled children and improvements are needed. Based on this study, we have identified four areas to raise the quality and inclusiveness of education for disabled children in early childhood education.

|

Area 1: To strengthen prioritisation of disabled children in ECEs, and accountability for how well they are doing

|

|

Area 2: To build leaders’ and teachers’ capabilities to teach and support disabled children

|

|

Area 3: To empower disabled children’s parents and whānau by increasing their understanding of their education rights, how to raise concerns or complaints, or how to get someone to advocate on their behalf

|

|

Area 4: To improve the coordination of supports for disabled children, and pathways from ECE to schools

|

Conclusion

Together, these recommendations have the potential to significantly improve education experiences and outcomes for disabled learners. Improving education for these learners can dramatically improve their lives and life course. It will take coordinated and focused work across the relevant agencies to take these recommendations forward and ensure change occurs. We recommend agencies report to Ministers on progress in July 2023.

Quality early childhood education (ECE) affects how well disabled children do at school and in life – from academic achievement and earning potential, to health and wellbeing.

The Education Review Office (ERO), in partnership with the Human Rights Commission (HRC) and the Office for Disability Issues (ODI), looked at how well the education system is supporting disabled children in early childhood education. We found that too many disabled children are excluded from ECE and, while many services provide safe and nurturing environments, we need to strengthen teaching practices. This report describes what we found and what is needed to significantly improve education for these priority learners.

Participation in high-quality ECE positively impacts a range of education and life outcomes including health, wellbeing, academic achievement, and earning potential. High‑quality ECE supports children to develop the social, emotional, communication, cognitive, and motor skills which enable them to thrive. A focused, intentional approach to developing these skills is particularly critical for disabled children as it sets the foundation for their future learning and engagement with others. Research shows that the greater the participation in ECE, the greater its impact.

Disabled children and young people have the same rights to enrol and receive education as other learners. To thrive, they need to be able to enrol in and access early childhood education, be fully included in all aspects, and have the curriculum adapted to their needs. Like all learners, they need to receive quality teaching, in supportive environments, and with strong partnerships between their kaiako and their parents and whānau.

This study looked at the quality and inclusiveness of education provision for disabled children in early childhood education. It answers four key questions:

- How well are disabled children doing?

- What is the quality and inclusiveness of education provision (including teaching practice)?

- How strong are the system enablers that support more inclusive and higher quality education?

- What key actions could lead to improved outcomes for disabled learners?

How well are disabled children doing?

Disabled children enjoy ECE, feel safe and that they belong. We found disabled children are participating and enjoying ECE. Most parents and whānau believe their child feels loved and cared for, and that they belong at their service.

Disabled children are being excluded from enrolling and fully participating. We found a significant number of parents and whānau are being discouraged from enrolling their disabled child, and are asked to keep their disabled child home for specific activities. Kaiako also lack confidence about including disabled children in some activities.

We do not know how well disabled children are progressing. We found many services lack information showing how well disabled children are progressing, and do not communicate children’s next steps with their parents and whānau.

Children with complex needs are doing less well. Children with complex needs experience exclusion more than their disabled peers with less complex needs. Kaiako are less likely to discuss children’s learning with their parents and whānau. Parents and whānau of children with complex needs are less likely to report their child feels safe and that they belong.

Which areas of education for disabled children could be strengthened?

We found many committed early childhood services, and a range of good practice in providing education and support for disabled children. But we also found four areas that could be strengthened.

- Kaiako are not confident teaching disabled children, and struggle to access support to help them develop. Kaiako confidence in teaching disabled children is low. A third of kaiako do not feel confident enough to deliver a curriculum that is inclusive of disabled children. Targeted professional learning and development, and experience supporting disabled children, improves kaiako confidence. Accessing development and capability-building support is an ongoing challenge.

- Partnerships with whānau need to be more focused on their child’s learning. Discussions with parents and whānau often focus on what has happened during the day rather than how learning is progressing. Parents and whānau are often not aware of how well their child is progressing. Only two-thirds of parents and whānau are satisfied with their involvement in developing and reviewing their child’s Individual Learning Plan (ILP), a critical component of a disabled child’s learning support.

- Services need to have a better understanding of how well disabled children are progressing, and how good their provision is. Many services do not have good information about how well they are providing for disabled children, and many lack focus on this important group. Forty-one percent of leaders reported provision for disabled children is rarely or never a focus of internal evaluation. We also found that service leaders are much more positive about the quality of provision for disabled children than parents/whānau or kaiako, further highlighting the lack of clarity on quality of provision.

- Transitions from ECE to schools are not working as well as entry into ECE. Transitions from ECE into school settings are not working well. Nearly a quarter of parents and whānau are not satisfied with how their child is supported when transitioning to school. Communication with and the sharing of information between ECEs, support services, and teachers is a challenge. The need to re-establish the case for their child’s need for support, and navigating the system, is also a challenge for parents and whānau.

Recommendations

Early childhood education is still not delivering for all disabled children and improvements are needed. Based on this study, we have identified four areas to raise the quality and inclusiveness of education for disabled children in early childhood education.

|

Area 1: To strengthen prioritisation of disabled children in ECEs, and accountability for how well they are doing

|

|

Area 2: To build leaders’ and teachers’ capabilities to teach and support disabled children

|

|

Area 3: To empower disabled children’s parents and whānau by increasing their understanding of their education rights, how to raise concerns or complaints, or how to get someone to advocate on their behalf

|

|

Area 4: To improve the coordination of supports for disabled children, and pathways from ECE to schools

|

Conclusion

Together, these recommendations have the potential to significantly improve education experiences and outcomes for disabled learners. Improving education for these learners can dramatically improve their lives and life course. It will take coordinated and focused work across the relevant agencies to take these recommendations forward and ensure change occurs. We recommend agencies report to Ministers on progress in July 2023.

About this report

Te Whāriki – The Early Childhood Curriculum is the core document supporting the delivery of quality early childhood education in Aotearoa New Zealand. The curriculum was refreshed in 2017, strengthening its focus on inclusion for all children. Five years on, ERO sees strong, inclusive practice in many aspects of early childhood education. This report looks at the quality and inclusiveness of education for disabled children in English medium early childhood services, and how it can be improved.

ERO is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early learning services, kura, and schools. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports learners’ outcomes – in this case, we are looking at education for disabled children in early childhood education services.

This report describes what we found about the quality and inclusiveness of education for disabled children in early childhood services.[a] It highlights the strengths and weaknesses of education provision, and suggests areas for improvement.

The voices of disabled children’s parents and whānau are an important element of this report. We include their experiences of their child’s participation, learning and outcomes, and how teaching practices impact on disabled children’s learning and lives.

We partnered with experts

For this evaluation, ERO partnered with the Human Rights Commission (HRC) and the Office for Disability Issues (ODI) to pool our collective expertise and independent advisory roles.

The Human Rights Commission is Aotearoa New Zealand’s national human rights institution. It is independent of Government and monitors the progress Aotearoa New Zealand is making towards the realisation of human rights. The Disability Rights Commissioner sits within the Human Rights Commission, and has a broad mandate to protect and promote the rights of disabled New Zealanders.

The Office for Disability Issues is focused on helping Aotearoa New Zealand work towards being a non-disabling society. It supports the implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) and the New Zealand Disability Strategy.

We also worked closely with an Expert Advisory Group with a range of expertise, including lived experience of disability, academics, practitioners, and agency officials.

ERO regularly evaluates the quality of education for disabled learners

As part of ERO’s mandate, we undertake national evaluations on education for disabled learners in schools and early childhood services. Disabled children are a priority group in all of ERO’s early childhood evaluations. Our last national report on the quality of provision for disabled children in early childhood education (ECE) was published in 2012. This latest report builds on ERO’s previous studies by investigating the quality of provision and outcomes for disabled children in greater detail, and draws on a wider range of voices.

This report is one of two focusing on provision of education for disabled learners, from early childhood through to secondary school

ERO, HRC, and ODI wanted to know if disabled children, from early childhood through to the end of secondary school, are receiving quality education. This report shares what we learnt about provision for children in English medium early childhood education settings. Its companion report shares what we learnt about provision for learners in English medium state and state-integrated schools.

The two companion evaluations have been designed to ask the same big questions, consider similar groups of learners, and are based on the same principles. The definitions for what ‘good’ looks like are also similar.

What we looked at

This evaluation looked at the quality and inclusiveness of education for disabled children in ECE. We answered four key questions:

- How well are disabled children doing?

- What is the quality and inclusivity of early childhood education provision (including teaching practice) for disabled children?

- How strong are the system enablers that support more inclusive and higher quality education?

- What key actions could lead to improved outcomes for disabled children?

This report focuses on education provision. However, although the following areas are important aspects of quality education provision for disabled children, we did not evaluate the quality of:

- needs assessment regarding health support

- early identification

- early intervention programmes

- specialist providers.

Where we looked

We focused our investigation on English medium early childhood services. To ensure we captured a range of experiences across a variety of learning contexts, ERO included kindergartens, education and care services, home-based services, and Playcentres in this evaluation.

How we evaluated education provision

We have taken a robust, mixed-methods approach to deliver breadth and depth in this evaluation.

To understand how good education is for disabled children we gathered information in multiple ways:

- surveys with 118 responses from parents/whānau

- surveys of 130 kaiako[b] and 291 service leaders

- site visits and observations of teaching and learning at nine services

- in-depth interviews with leaders, kaiako, and parents/whānau at 22 services, and with leaders and kaiako at an additional two services

- interviews with eight Governing Organisation[c] leaders

- interviews with key experts, practitioners, and agencies supporting inclusive education.

Further details of the methods we used are in Appendix 1.

How this fits with other work

This report provides up-to-date information on the quality of provision for disabled children in ECE services, and informs future provision, including the Ministry of Education’s Highest Needs Review.

Report structure

This report has 11 parts.

- Part 1 sets out who disabled learners are, and the system that supports their education.

- Part 2 explains why early childhood education is important for disabled children, and what drives good outcomes.

- Part 3 shares our findings about education experiences and outcomes for disabled children in ECE.

- Part 4 outlines the differences in experiences and outcomes for different groups of disabled children.

- Part 5 describes the quality of education and care provision for disabled children.

- Part 6 details the differences in provision between different types of services.

- Part 7 shares the experiences and quality of provision for Māori disabled children.

- Part 8 shares the experiences and quality of provision for Pacific disabled children.

- Part 9 explores the system that supports provision for disabled children in ECE.

- Part 10 details our key findings, and areas for action.

- Part 11 sets out the next steps to drive improvement for disabled children in ECE.

Te Whāriki – The Early Childhood Curriculum is the core document supporting the delivery of quality early childhood education in Aotearoa New Zealand. The curriculum was refreshed in 2017, strengthening its focus on inclusion for all children. Five years on, ERO sees strong, inclusive practice in many aspects of early childhood education. This report looks at the quality and inclusiveness of education for disabled children in English medium early childhood services, and how it can be improved.

ERO is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early learning services, kura, and schools. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports learners’ outcomes – in this case, we are looking at education for disabled children in early childhood education services.

This report describes what we found about the quality and inclusiveness of education for disabled children in early childhood services.[a] It highlights the strengths and weaknesses of education provision, and suggests areas for improvement.

The voices of disabled children’s parents and whānau are an important element of this report. We include their experiences of their child’s participation, learning and outcomes, and how teaching practices impact on disabled children’s learning and lives.

We partnered with experts

For this evaluation, ERO partnered with the Human Rights Commission (HRC) and the Office for Disability Issues (ODI) to pool our collective expertise and independent advisory roles.

The Human Rights Commission is Aotearoa New Zealand’s national human rights institution. It is independent of Government and monitors the progress Aotearoa New Zealand is making towards the realisation of human rights. The Disability Rights Commissioner sits within the Human Rights Commission, and has a broad mandate to protect and promote the rights of disabled New Zealanders.

The Office for Disability Issues is focused on helping Aotearoa New Zealand work towards being a non-disabling society. It supports the implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) and the New Zealand Disability Strategy.

We also worked closely with an Expert Advisory Group with a range of expertise, including lived experience of disability, academics, practitioners, and agency officials.

ERO regularly evaluates the quality of education for disabled learners

As part of ERO’s mandate, we undertake national evaluations on education for disabled learners in schools and early childhood services. Disabled children are a priority group in all of ERO’s early childhood evaluations. Our last national report on the quality of provision for disabled children in early childhood education (ECE) was published in 2012. This latest report builds on ERO’s previous studies by investigating the quality of provision and outcomes for disabled children in greater detail, and draws on a wider range of voices.

This report is one of two focusing on provision of education for disabled learners, from early childhood through to secondary school

ERO, HRC, and ODI wanted to know if disabled children, from early childhood through to the end of secondary school, are receiving quality education. This report shares what we learnt about provision for children in English medium early childhood education settings. Its companion report shares what we learnt about provision for learners in English medium state and state-integrated schools.

The two companion evaluations have been designed to ask the same big questions, consider similar groups of learners, and are based on the same principles. The definitions for what ‘good’ looks like are also similar.

What we looked at

This evaluation looked at the quality and inclusiveness of education for disabled children in ECE. We answered four key questions:

- How well are disabled children doing?

- What is the quality and inclusivity of early childhood education provision (including teaching practice) for disabled children?

- How strong are the system enablers that support more inclusive and higher quality education?

- What key actions could lead to improved outcomes for disabled children?

This report focuses on education provision. However, although the following areas are important aspects of quality education provision for disabled children, we did not evaluate the quality of:

- needs assessment regarding health support

- early identification

- early intervention programmes

- specialist providers.

Where we looked

We focused our investigation on English medium early childhood services. To ensure we captured a range of experiences across a variety of learning contexts, ERO included kindergartens, education and care services, home-based services, and Playcentres in this evaluation.

How we evaluated education provision

We have taken a robust, mixed-methods approach to deliver breadth and depth in this evaluation.

To understand how good education is for disabled children we gathered information in multiple ways:

- surveys with 118 responses from parents/whānau

- surveys of 130 kaiako[b] and 291 service leaders

- site visits and observations of teaching and learning at nine services

- in-depth interviews with leaders, kaiako, and parents/whānau at 22 services, and with leaders and kaiako at an additional two services

- interviews with eight Governing Organisation[c] leaders

- interviews with key experts, practitioners, and agencies supporting inclusive education.

Further details of the methods we used are in Appendix 1.

How this fits with other work

This report provides up-to-date information on the quality of provision for disabled children in ECE services, and informs future provision, including the Ministry of Education’s Highest Needs Review.

Report structure

This report has 11 parts.

- Part 1 sets out who disabled learners are, and the system that supports their education.

- Part 2 explains why early childhood education is important for disabled children, and what drives good outcomes.

- Part 3 shares our findings about education experiences and outcomes for disabled children in ECE.

- Part 4 outlines the differences in experiences and outcomes for different groups of disabled children.

- Part 5 describes the quality of education and care provision for disabled children.

- Part 6 details the differences in provision between different types of services.

- Part 7 shares the experiences and quality of provision for Māori disabled children.

- Part 8 shares the experiences and quality of provision for Pacific disabled children.

- Part 9 explores the system that supports provision for disabled children in ECE.

- Part 10 details our key findings, and areas for action.

- Part 11 sets out the next steps to drive improvement for disabled children in ECE.

Part 1: Who are disabled children and what is the system that supports their education?

Participation in high-quality ECE positively impacts education and life outcomes, such as health, wellbeing, and earning potential. High-quality ECE supports children to develop the social, emotional, communication, cognitive, and motor skills which enable them to thrive. This is particularly critical for disabled children as it sets the foundation for their future learning and engagement with others. Research shows that the greater the participation in ECE, the greater its impact.

Early childhood education has traditionally taken an inclusive approach that is welcoming of disabled children. Te Whāriki – The Early Childhood Curriculum explicitly describes the expectation to include “children with diversity of ability and learning needs.”[1]

In this section, we describe what we mean by “disabled children”. We also provide a brief overview of the support they receive for their early childhood education.

Who are disabled children?

Disabled children are defined in this report as all children with significant needs for ongoing support and adaptations or accommodations to enable them to thrive in education.

We use the term “disabled children” as it is consistent with the New Zealand Disability Strategy[d] which defines disability as something that happens when people with impairments face barriers in society. This is referred to as the social model of disability, which is embodied in the United Nations Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD).

Disabled children are a highly diverse group. Examples include children with:

- physical impairments (such as Cerebral Palsy, Muscular Dystrophy) and have significant challenges, for example, walking or climbing steps

- intellectual or cognitive impairments caused by genetic disorders (such as Down Syndrome, Fragile X Syndrome, Prader-Willi Syndrome) and have significant challenges, for example, learning things at ECE

- sensory impairments (such as deafblind, blind, low vision, deaf, and hard of hearing) and have significant challenges, for example, seeing or hearing

- neurodiverse learning needs (such as those relating to dyslexia, dyspraxia, and autism spectrum disorder) and have significant challenges, for example, managing their emotions or relating to others.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, it is estimated that 11 percent of children aged under 15 years are disabled.[2] There is a higher rate of disability amongst Māori; the disability rate for Māori children is estimated to be 14 percent, compared to 11 percent for all children.[3]

There are clear expectations for inclusion for disabled children in ECE

Expectations for inclusion of disabled children are clearly laid out in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (the UNCRPD).

Under the UNCRPD, all children, including disabled children, have the right to education without discrimination and on the basis of equal opportunity. They may not be discriminated against through enrolment or exclusion from learning opportunities or activities. Aotearoa New Zealand ratified the UNCRPD in 2008.

This means the education system must be inclusive. An inclusive education system is one that accommodates all learners, whatever their abilities or requirements, and at all levels, including ECE.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s early childhood curriculum – Te Whāriki (2017) – is explicit about inclusion for children with additional needs or disability.[4]

While there are high expectations for disabled children’s inclusion, participation is not compulsory – families can choose not to enrol their children in ECE. Many ECE providers are private businesses, and children’s attendance at ECE is not fully funded.

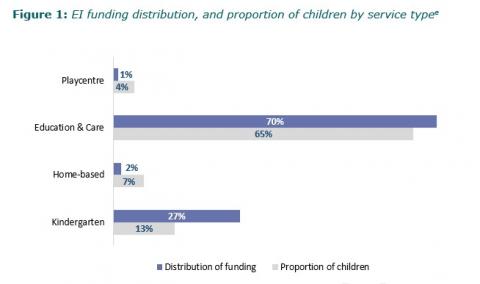

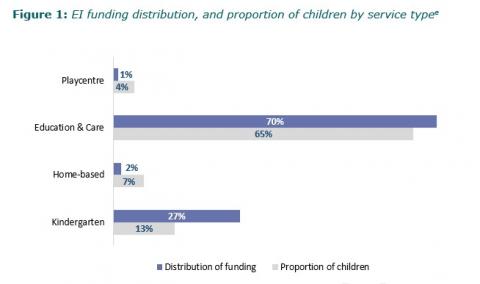

There is limited system level information on disabled children in ECE

There is currently very limited data on disabled learners across the education system. This is particularly so for the ECE sector, as there is no national reporting mechanism or requirement to provide information on disabled children. Consequently, we have had to rely on data for those who receive Early Intervention (EI) funding to get some understanding on the participation of these learners.

From this data we know that, of the 190,348 children enrolled in ECE in Aotearoa New Zealand, a proportion are assigned 6,252 Early Intervention (EI) funding units. Although this provides some insight into the number of children receiving government support, funding units is not an accurate indication of how many disabled children there are, or how many attend an ECE service. This is because not every disabled child receives EI funding, and for those children who do receive funding, one child may receive several funding units, depending on the complexity and/or intensity of their needs. EI funding is therefore an indication of support needed rather than the number of disabled children enrolled in ECE[5].

Figure 1: EI funding distribution, and proportion of children by service type[e]

Where are disabled children and how do they move between settings?

Disabled children are enrolled in a wide range of services. In this report, we evaluated how well things were going for disabled children across four different service types.

- Education and care services: These cover a diverse range of services including standalone services, and services that are part of a large network of services under a single organisation. These may be community-based or private, and include different organising philosophies such as Montessori or Rudolf Steiner.

- Kindergartens: These are state funded and run on a non-profit model. Their operating hours typically align with schools, including term breaks. These services use 100 percent qualified teachers, and unqualified teaching assistants or aides. Most kindergartens enrol children aged over two years.

- Home-based networks: Early childhood education is provided in a home setting rather than a centre. An educator provides education and care for up to four children aged from birth to five years.

- Playcentres: These services run a non-profit model and rely on parent volunteers. This type of service has a special licensing agreement with the Ministry of Education which enables them to run sessions with adults (usually parents) who hold Playcentre-specific qualifications.

There is little difference between which service types disabled and non-disabled children attend, although there is a slightly higher proportion of disabled children in centre-based care.[f], [6] Ministry of Education (MoE) data shows around 13 percent of children receiving funding for early intervention services are not in any early childhood service.

How are disabled children supported?

Targeted support

The Ministry of Education provides targeted support for disabled children through the Early Intervention Service (EIS).[7] In some areas, Child Development Teams also provide support.[8] This support is available for children who qualify, whether they are enrolled in an ECE service or not. Children do not need a formal diagnosis to access EI support, and parents or kaiako can request it. EIS and Child Development Teams are government funded.

EIS providers work with parents, whānau, and kaiako to develop plans for children’s participation and learning. In some cases, this might involve targeted training to give whānau and kaiako strategies to support the child’s learning. In others, this might involve an Education Support Worker (ESW) being funded to attend the service to offer on‑the‑ground support for the child, and for kaiako, during the day.

General support

For disabled children who do not qualify for Early Intervention support, kaiako work with their parents and whānau to understand their child’s strengths, interests, and needs. Kaiako then develop a plan with the disabled child’s parents/whānau for how to support the child’s learning and development in the service.

ECE services may also apply to the Ministry of Education for equity funding to support disabled children under:

- funding for special needs (disabled children)

- funding for languages and cultures other than English (including sign language).[9]

Services may choose how they use their equity funding based on which children and purposes they have received it for. Service leaders must report annually to parents and the community on how they use the equity funding.

Participation in high-quality ECE positively impacts education and life outcomes, such as health, wellbeing, and earning potential. High-quality ECE supports children to develop the social, emotional, communication, cognitive, and motor skills which enable them to thrive. This is particularly critical for disabled children as it sets the foundation for their future learning and engagement with others. Research shows that the greater the participation in ECE, the greater its impact.

Early childhood education has traditionally taken an inclusive approach that is welcoming of disabled children. Te Whāriki – The Early Childhood Curriculum explicitly describes the expectation to include “children with diversity of ability and learning needs.”[1]

In this section, we describe what we mean by “disabled children”. We also provide a brief overview of the support they receive for their early childhood education.

Who are disabled children?

Disabled children are defined in this report as all children with significant needs for ongoing support and adaptations or accommodations to enable them to thrive in education.

We use the term “disabled children” as it is consistent with the New Zealand Disability Strategy[d] which defines disability as something that happens when people with impairments face barriers in society. This is referred to as the social model of disability, which is embodied in the United Nations Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD).

Disabled children are a highly diverse group. Examples include children with:

- physical impairments (such as Cerebral Palsy, Muscular Dystrophy) and have significant challenges, for example, walking or climbing steps

- intellectual or cognitive impairments caused by genetic disorders (such as Down Syndrome, Fragile X Syndrome, Prader-Willi Syndrome) and have significant challenges, for example, learning things at ECE

- sensory impairments (such as deafblind, blind, low vision, deaf, and hard of hearing) and have significant challenges, for example, seeing or hearing

- neurodiverse learning needs (such as those relating to dyslexia, dyspraxia, and autism spectrum disorder) and have significant challenges, for example, managing their emotions or relating to others.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, it is estimated that 11 percent of children aged under 15 years are disabled.[2] There is a higher rate of disability amongst Māori; the disability rate for Māori children is estimated to be 14 percent, compared to 11 percent for all children.[3]

There are clear expectations for inclusion for disabled children in ECE

Expectations for inclusion of disabled children are clearly laid out in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (the UNCRPD).

Under the UNCRPD, all children, including disabled children, have the right to education without discrimination and on the basis of equal opportunity. They may not be discriminated against through enrolment or exclusion from learning opportunities or activities. Aotearoa New Zealand ratified the UNCRPD in 2008.

This means the education system must be inclusive. An inclusive education system is one that accommodates all learners, whatever their abilities or requirements, and at all levels, including ECE.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s early childhood curriculum – Te Whāriki (2017) – is explicit about inclusion for children with additional needs or disability.[4]

While there are high expectations for disabled children’s inclusion, participation is not compulsory – families can choose not to enrol their children in ECE. Many ECE providers are private businesses, and children’s attendance at ECE is not fully funded.

There is limited system level information on disabled children in ECE

There is currently very limited data on disabled learners across the education system. This is particularly so for the ECE sector, as there is no national reporting mechanism or requirement to provide information on disabled children. Consequently, we have had to rely on data for those who receive Early Intervention (EI) funding to get some understanding on the participation of these learners.

From this data we know that, of the 190,348 children enrolled in ECE in Aotearoa New Zealand, a proportion are assigned 6,252 Early Intervention (EI) funding units. Although this provides some insight into the number of children receiving government support, funding units is not an accurate indication of how many disabled children there are, or how many attend an ECE service. This is because not every disabled child receives EI funding, and for those children who do receive funding, one child may receive several funding units, depending on the complexity and/or intensity of their needs. EI funding is therefore an indication of support needed rather than the number of disabled children enrolled in ECE[5].

Figure 1: EI funding distribution, and proportion of children by service type[e]

Where are disabled children and how do they move between settings?

Disabled children are enrolled in a wide range of services. In this report, we evaluated how well things were going for disabled children across four different service types.

- Education and care services: These cover a diverse range of services including standalone services, and services that are part of a large network of services under a single organisation. These may be community-based or private, and include different organising philosophies such as Montessori or Rudolf Steiner.

- Kindergartens: These are state funded and run on a non-profit model. Their operating hours typically align with schools, including term breaks. These services use 100 percent qualified teachers, and unqualified teaching assistants or aides. Most kindergartens enrol children aged over two years.

- Home-based networks: Early childhood education is provided in a home setting rather than a centre. An educator provides education and care for up to four children aged from birth to five years.

- Playcentres: These services run a non-profit model and rely on parent volunteers. This type of service has a special licensing agreement with the Ministry of Education which enables them to run sessions with adults (usually parents) who hold Playcentre-specific qualifications.

There is little difference between which service types disabled and non-disabled children attend, although there is a slightly higher proportion of disabled children in centre-based care.[f], [6] Ministry of Education (MoE) data shows around 13 percent of children receiving funding for early intervention services are not in any early childhood service.

How are disabled children supported?

Targeted support

The Ministry of Education provides targeted support for disabled children through the Early Intervention Service (EIS).[7] In some areas, Child Development Teams also provide support.[8] This support is available for children who qualify, whether they are enrolled in an ECE service or not. Children do not need a formal diagnosis to access EI support, and parents or kaiako can request it. EIS and Child Development Teams are government funded.

EIS providers work with parents, whānau, and kaiako to develop plans for children’s participation and learning. In some cases, this might involve targeted training to give whānau and kaiako strategies to support the child’s learning. In others, this might involve an Education Support Worker (ESW) being funded to attend the service to offer on‑the‑ground support for the child, and for kaiako, during the day.

General support

For disabled children who do not qualify for Early Intervention support, kaiako work with their parents and whānau to understand their child’s strengths, interests, and needs. Kaiako then develop a plan with the disabled child’s parents/whānau for how to support the child’s learning and development in the service.

ECE services may also apply to the Ministry of Education for equity funding to support disabled children under:

- funding for special needs (disabled children)

- funding for languages and cultures other than English (including sign language).[9]

Services may choose how they use their equity funding based on which children and purposes they have received it for. Service leaders must report annually to parents and the community on how they use the equity funding.

Part 2. What sort of education provision drives good outcomes for disabled children in ECE?

Participation in high-quality early childhood education positively impacts children – both in their education and their longer-term life outcomes. It is critical that disabled children experience a focused, intentional approach to their early learning and development as this sets the foundation for all their future learning and engagement with others.

This section explains the importance of ECE for disabled children, and what learning outcomes matter. We then set out what quality inclusive education looks like for disabled children in ECE based on the best evidence from Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally.

Why is ECE important for disabled children?

International research tells us that participation in quality ECE lays a strong foundation for better education and life outcomes later, particularly for children who experience more challenges.[10]Although all children benefit from ECE’s impacts on neurological, linguistic, and social and emotional skills development, benefits are particularly impactful for disabled children.[11] Quality ECE for disabled children supports critical outcomes such as the development of sense of belonging, participation in learning and social activities, and relationships – all of which support academic learning and wellbeing.[12]

What outcomes matter for disabled children?

Te Whāriki sets out the outcomes ECE seeks to achieve for all learners, including disabled children. The 20 learning outcomes sit across five learning area strands:[13]

|

Strand |

Aim |

|

Wellbeing | Mana atua |

The health and wellbeing of the child is protected and nurtured. |

|

Belonging | Mana whenua |

Children and their families feel a sense of belonging. |

|

Contribution | Mana tangata |

Opportunities for learning are equitable, and each child’s contribution is valued. |

|

Communication | Mana reo |

The languages and symbols of children’s own and other cultures are promoted and protected. |

|

Exploration | Mana aotūroa |

The child learns through active exploration of the environment. |

The full list of outcomes is in Appendix 3.

What are the components of quality ECE for disabled children?

To understand what quality, inclusive education looks like for disabled children, we carried out an extensive review of Aotearoa New Zealand and international literature on best practice evidence. We then worked with an Expert Advisory Group of people with lived experience of disability, academics, practitioners, and agency officials to identify four key components of quality, inclusive education practice.

|

Components of quality, inclusive education practice |

|

For each component of quality, inclusive practice we used the literature evidence base to define what good looks like, and a four-point scale for judging provision. Indicators for culturally responsive factors like working with whānau and prioritising Te Tiriti o Waitangi, were embedded throughout the components.

Much of the Aotearoa New Zealand literature we drew on was from Māori academics. Our indicators and judgements are therefore also informed by mātauranga Māori concepts of disability.

The next sections explain what each component covers. The full rubric we used to judge quality against each component can be found in Appendix 2.

-

Effective leadership and strong expectations for inclusion of disabled children

Informed and committed leadership is essential. The knowledge and beliefs held by leaders, combined with the culture they promote, have a fundamental influence on how welcomed and valued disabled children and their parents and whānau feel, and on disabled children’s education outcomes. Leaders include centre managers, pedagogical leaders and senior teachers/kaiako.

From the evidence base on best practice, we identified the following aspects of leadership as most important.

- Clear expectations: Do leaders set clear expectations for equity and inclusion, wellbeing, and achievement for disabled children?

- Planning for and prioritising disabled children’s success: Do leaders prioritise disabled children’s success when making plans for the service?

- Welcoming culture and values: Do leaders promote a culture that values disabled children and their whānau?

- Alignment of policies and practices: Do leaders ensure policies and practices align, and are underpinned by a vision for inclusion and equity?

- Information used to strengthen practice: Do leaders use information effectively to promote better inclusive practices and greater equity of outcomes for disabled children?

-

Quality teaching

Quality, intentional teaching plays a critical role in creating equity in engagement, progress, and achievement for disabled children.

A responsive curriculum in ECE involves both planned and spontaneous learning experiences. Kaiako should draw on up-to-date knowledge of how children learn and develop, and understand the service’s philosophy, to bring these to life in their teaching practice. Kaiako are expected to use assessment information and a wide range of teaching strategies to respond effectively to the different ways in which children learn.[14]

We identified the following elements as important when considering the quality of curriculum, teaching, and assessment for disabled children.

- Responsive curriculum: Do kaiako adapt the learning programme in response to disabled children’s strengths, interests and needs, language, culture, and identity?

- Intentional teaching practice: Do kaiako adapt their teaching practice to ensure disabled children are able to fully participate in learning?

- Culturally responsive teaching for Māori disabled children: Do kaiako ensure that, while the curriculum is bicultural for all children, they work with Māori children’s parents and whānau to understand what success looks like for them?

- Assessment: Do kaiako use appropriate assessment to understand what disabled children know and can do, and identify potential next steps for learning?

- Inclusive social and emotional environment: Do kaiako support children’s social and emotional learning to promote their wellbeing and participation?

-

Inclusive, accessible environments

Physical access to buildings, playgrounds, and excursions is essential for disabled children to feel fully included in the life of the service.

We identified two aspects of the physical environment as being important for ensuring inclusive provision for disabled children.

- Accessible spaces: Are physical environments designed to support safe, mana‑enhancing, and barrier-free access to learning and social opportunities for disabled children?

- Specialised resources and adaptations: Are appropriate resources and equipment available to support full participation of disabled children in all activities and are designated spaces available to support self-regulation?

-

Strong, learning-focused partnerships with parents and whānau

Parents and whānau are a child’s first and most important teachers and have a vital role to play in helping them learn. Parents and whānau know their child better than anyone – their strengths, interests and needs, the ways they approach new and different things, and how they learn.[15]

We identified the following learner and parent and whānau engagement practices to be most important for disabled children.

- Educationally-focused engagement: Do kaiako, leaders, and parents/whānau have strong relationships, which underpin learning-focused partnerships, to support disabled children’s learning and success, including through developing and reviewing their child’s individual learning plan?

- Whānau agency: Is parent and whānau agency encouraged, for example through codesigning service policies for disabled children, and providing feedback on provision for disabled children?

What enables services to provide quality, inclusive education for disabled children?

Services need support to provide quality, inclusive education for disabled children. Our analysis identified five key enablers, set out in the following table. For each one we identified themes for what needs to be in place at a structural and/or system level, for quality, inclusive practice for disabled children to occur.

|

System-level enablers supporting services to provide quality, inclusive education for disabled children |

|

-

High expectations for inclusion and equity for disabled children

Based on comparative international education systems and policy research,[16] and Aotearoa New Zealand’s obligations to Te Tiriti o Waitangi, we identified the following aspects of strong system-level expectations.

- Clear expectations are set: Do education legislation, policies, and plans articulate clear expectations for inclusion and equity in education for disabled children?

- Expectations are understood: Do kaiako and leaders have a clear understanding of the expectations and what they mean for their practice?

- Expectations are acted on: Do service leaders and kaiako have a clear understanding of the education system’s expectations for inclusion, and enact the expectations?

-

Workforce capability and capacity

Workforce in the ECE context includes kaiako, leaders, education support workers and other specialists involved in designing and delivering support for disabled children.

International research suggests a focus on education for disabled children is required in Initial Teacher Education (ITE), specialist training programmes, and ongoing professional learning. This would support the education workforce to plan responsive learning opportunities to improve disabled children’s engagement and learning.

When considering the skills and confidence of the ECE workforce, we explored two areas.

- Kaiako confidence and capability: Do kaiako have the skills and confidence needed to deliver quality and inclusive education for disabled children?

- Ongoing learning: Are kaiako and learning support staff supported to improve their skills in education practice for disabled children?

-

Inter-agency collaboration

Evidence shows countries that report better outcomes for disabled people have system-level alignment of policies across government departments, and agencies work together to achieve the goals of inclusion and equity in education.[17] Sharing information and knowledge for better collaboration and coordination of services improves efficiencies in how support is delivered and optimises the use of available resources.

When evaluating the quality of collaboration to support high-quality provision for disabled children, we considered:

- Collaboration with support services: Do services have timely access to support agencies, and do they work well together?

- Collaboration with other ECE services and schools: How well do agencies and ECE services work together to provide support for kaiako, children, and their parents/whānau?

-

Good transitions

Transitions are a crucial time for all learners, but for disabled children they are critical to their engagement and success in learning in new environments. Flexible transition plans, responsive to the needs of the individual disabled child and their whānau, need to be developed in partnership with all the agencies and organisations involved.

We explored how well coordinated entry into ECE was, as well as the quality of transitions between ECE and schools.

- Entry into ECE: Is disabled children’s entry into ECE well planned, coordinated, and responsive to their individual needs?

- Through or between ECE services: Are disabled children's transitions between rooms in a service or between different ECE services well-planned, coordinated, and responsive to individual needs?

- Transitions from ECE to schools: Is the transition from ECE to school well planned, coordinated, and responsive to individual disabled learners? Do agencies and educational institutions communicate and work well together to support the learner and their whānau?

-

System monitoring, evaluation, and accountability

The importance of gathering data for this group of learners at a national level has been emphasised in international literature. The Global Education Monitoring Report (2020) identified the shortage of data on disabled learners at a national level, and the impact this has on evidence-informed policy development in the jurisdictions covered. The issue of invisibility of disabled learners, poor benchmarks for monitoring progress or effectiveness of inclusive education programmes, and its link to poor monitoring of outcomes for disabled learners, has been highlighted in multiple international reports.

When identifying the scope of system monitoring, evaluation, and accountability, we considered three key areas.

- Data is collected: Is relevant data about participation, engagement, and achievement of all disabled children effectively and systematically collected and analysed nationally?

- Evidence is used: Are evidence and insights from data used to inform policies and plans?

- The system is held accountable: Are services and agencies held accountable for the inclusion of disabled children and the quality of provision they receive?

Conclusion

Inclusive education for disabled children needs to be planned for and supported. This section set out key elements of quality education for disabled children in ECE. The next section describes the outcomes we found for disabled children in ECE, followed by the elements of provision that led to those outcomes.

Participation in high-quality early childhood education positively impacts children – both in their education and their longer-term life outcomes. It is critical that disabled children experience a focused, intentional approach to their early learning and development as this sets the foundation for all their future learning and engagement with others.

This section explains the importance of ECE for disabled children, and what learning outcomes matter. We then set out what quality inclusive education looks like for disabled children in ECE based on the best evidence from Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally.

Why is ECE important for disabled children?

International research tells us that participation in quality ECE lays a strong foundation for better education and life outcomes later, particularly for children who experience more challenges.[10]Although all children benefit from ECE’s impacts on neurological, linguistic, and social and emotional skills development, benefits are particularly impactful for disabled children.[11] Quality ECE for disabled children supports critical outcomes such as the development of sense of belonging, participation in learning and social activities, and relationships – all of which support academic learning and wellbeing.[12]

What outcomes matter for disabled children?

Te Whāriki sets out the outcomes ECE seeks to achieve for all learners, including disabled children. The 20 learning outcomes sit across five learning area strands:[13]

|

Strand |

Aim |

|

Wellbeing | Mana atua |

The health and wellbeing of the child is protected and nurtured. |

|

Belonging | Mana whenua |

Children and their families feel a sense of belonging. |

|

Contribution | Mana tangata |

Opportunities for learning are equitable, and each child’s contribution is valued. |

|

Communication | Mana reo |

The languages and symbols of children’s own and other cultures are promoted and protected. |

|

Exploration | Mana aotūroa |

The child learns through active exploration of the environment. |

The full list of outcomes is in Appendix 3.

What are the components of quality ECE for disabled children?

To understand what quality, inclusive education looks like for disabled children, we carried out an extensive review of Aotearoa New Zealand and international literature on best practice evidence. We then worked with an Expert Advisory Group of people with lived experience of disability, academics, practitioners, and agency officials to identify four key components of quality, inclusive education practice.

|

Components of quality, inclusive education practice |

|

For each component of quality, inclusive practice we used the literature evidence base to define what good looks like, and a four-point scale for judging provision. Indicators for culturally responsive factors like working with whānau and prioritising Te Tiriti o Waitangi, were embedded throughout the components.

Much of the Aotearoa New Zealand literature we drew on was from Māori academics. Our indicators and judgements are therefore also informed by mātauranga Māori concepts of disability.

The next sections explain what each component covers. The full rubric we used to judge quality against each component can be found in Appendix 2.

-

Effective leadership and strong expectations for inclusion of disabled children

Informed and committed leadership is essential. The knowledge and beliefs held by leaders, combined with the culture they promote, have a fundamental influence on how welcomed and valued disabled children and their parents and whānau feel, and on disabled children’s education outcomes. Leaders include centre managers, pedagogical leaders and senior teachers/kaiako.

From the evidence base on best practice, we identified the following aspects of leadership as most important.

- Clear expectations: Do leaders set clear expectations for equity and inclusion, wellbeing, and achievement for disabled children?

- Planning for and prioritising disabled children’s success: Do leaders prioritise disabled children’s success when making plans for the service?

- Welcoming culture and values: Do leaders promote a culture that values disabled children and their whānau?

- Alignment of policies and practices: Do leaders ensure policies and practices align, and are underpinned by a vision for inclusion and equity?

- Information used to strengthen practice: Do leaders use information effectively to promote better inclusive practices and greater equity of outcomes for disabled children?

-

Quality teaching

Quality, intentional teaching plays a critical role in creating equity in engagement, progress, and achievement for disabled children.

A responsive curriculum in ECE involves both planned and spontaneous learning experiences. Kaiako should draw on up-to-date knowledge of how children learn and develop, and understand the service’s philosophy, to bring these to life in their teaching practice. Kaiako are expected to use assessment information and a wide range of teaching strategies to respond effectively to the different ways in which children learn.[14]

We identified the following elements as important when considering the quality of curriculum, teaching, and assessment for disabled children.

- Responsive curriculum: Do kaiako adapt the learning programme in response to disabled children’s strengths, interests and needs, language, culture, and identity?

- Intentional teaching practice: Do kaiako adapt their teaching practice to ensure disabled children are able to fully participate in learning?

- Culturally responsive teaching for Māori disabled children: Do kaiako ensure that, while the curriculum is bicultural for all children, they work with Māori children’s parents and whānau to understand what success looks like for them?

- Assessment: Do kaiako use appropriate assessment to understand what disabled children know and can do, and identify potential next steps for learning?

- Inclusive social and emotional environment: Do kaiako support children’s social and emotional learning to promote their wellbeing and participation?

-

Inclusive, accessible environments

Physical access to buildings, playgrounds, and excursions is essential for disabled children to feel fully included in the life of the service.

We identified two aspects of the physical environment as being important for ensuring inclusive provision for disabled children.

- Accessible spaces: Are physical environments designed to support safe, mana‑enhancing, and barrier-free access to learning and social opportunities for disabled children?

- Specialised resources and adaptations: Are appropriate resources and equipment available to support full participation of disabled children in all activities and are designated spaces available to support self-regulation?

-

Strong, learning-focused partnerships with parents and whānau

Parents and whānau are a child’s first and most important teachers and have a vital role to play in helping them learn. Parents and whānau know their child better than anyone – their strengths, interests and needs, the ways they approach new and different things, and how they learn.[15]

We identified the following learner and parent and whānau engagement practices to be most important for disabled children.

- Educationally-focused engagement: Do kaiako, leaders, and parents/whānau have strong relationships, which underpin learning-focused partnerships, to support disabled children’s learning and success, including through developing and reviewing their child’s individual learning plan?

- Whānau agency: Is parent and whānau agency encouraged, for example through codesigning service policies for disabled children, and providing feedback on provision for disabled children?

What enables services to provide quality, inclusive education for disabled children?

Services need support to provide quality, inclusive education for disabled children. Our analysis identified five key enablers, set out in the following table. For each one we identified themes for what needs to be in place at a structural and/or system level, for quality, inclusive practice for disabled children to occur.

|

System-level enablers supporting services to provide quality, inclusive education for disabled children |

|

-

High expectations for inclusion and equity for disabled children

Based on comparative international education systems and policy research,[16] and Aotearoa New Zealand’s obligations to Te Tiriti o Waitangi, we identified the following aspects of strong system-level expectations.

- Clear expectations are set: Do education legislation, policies, and plans articulate clear expectations for inclusion and equity in education for disabled children?

- Expectations are understood: Do kaiako and leaders have a clear understanding of the expectations and what they mean for their practice?

- Expectations are acted on: Do service leaders and kaiako have a clear understanding of the education system’s expectations for inclusion, and enact the expectations?

-

Workforce capability and capacity

Workforce in the ECE context includes kaiako, leaders, education support workers and other specialists involved in designing and delivering support for disabled children.

International research suggests a focus on education for disabled children is required in Initial Teacher Education (ITE), specialist training programmes, and ongoing professional learning. This would support the education workforce to plan responsive learning opportunities to improve disabled children’s engagement and learning.

When considering the skills and confidence of the ECE workforce, we explored two areas.

- Kaiako confidence and capability: Do kaiako have the skills and confidence needed to deliver quality and inclusive education for disabled children?

- Ongoing learning: Are kaiako and learning support staff supported to improve their skills in education practice for disabled children?

-

Inter-agency collaboration

Evidence shows countries that report better outcomes for disabled people have system-level alignment of policies across government departments, and agencies work together to achieve the goals of inclusion and equity in education.[17] Sharing information and knowledge for better collaboration and coordination of services improves efficiencies in how support is delivered and optimises the use of available resources.

When evaluating the quality of collaboration to support high-quality provision for disabled children, we considered:

- Collaboration with support services: Do services have timely access to support agencies, and do they work well together?

- Collaboration with other ECE services and schools: How well do agencies and ECE services work together to provide support for kaiako, children, and their parents/whānau?

-

Good transitions

Transitions are a crucial time for all learners, but for disabled children they are critical to their engagement and success in learning in new environments. Flexible transition plans, responsive to the needs of the individual disabled child and their whānau, need to be developed in partnership with all the agencies and organisations involved.

We explored how well coordinated entry into ECE was, as well as the quality of transitions between ECE and schools.

- Entry into ECE: Is disabled children’s entry into ECE well planned, coordinated, and responsive to their individual needs?

- Through or between ECE services: Are disabled children's transitions between rooms in a service or between different ECE services well-planned, coordinated, and responsive to individual needs?

- Transitions from ECE to schools: Is the transition from ECE to school well planned, coordinated, and responsive to individual disabled learners? Do agencies and educational institutions communicate and work well together to support the learner and their whānau?

-

System monitoring, evaluation, and accountability

The importance of gathering data for this group of learners at a national level has been emphasised in international literature. The Global Education Monitoring Report (2020) identified the shortage of data on disabled learners at a national level, and the impact this has on evidence-informed policy development in the jurisdictions covered. The issue of invisibility of disabled learners, poor benchmarks for monitoring progress or effectiveness of inclusive education programmes, and its link to poor monitoring of outcomes for disabled learners, has been highlighted in multiple international reports.

When identifying the scope of system monitoring, evaluation, and accountability, we considered three key areas.

- Data is collected: Is relevant data about participation, engagement, and achievement of all disabled children effectively and systematically collected and analysed nationally?

- Evidence is used: Are evidence and insights from data used to inform policies and plans?

- The system is held accountable: Are services and agencies held accountable for the inclusion of disabled children and the quality of provision they receive?

Conclusion

Inclusive education for disabled children needs to be planned for and supported. This section set out key elements of quality education for disabled children in ECE. The next section describes the outcomes we found for disabled children in ECE, followed by the elements of provision that led to those outcomes.

Part 3: What are the education experiences and outcomes for disabled children?

Most parents report their disabled child has a sense of belonging at their service and enjoys attending, but not all services are welcoming of disabled children. Unfortunately, a significant number of disabled children are still being discouraged from enrolling, and asked to stay home when their peers participate in certain activities.

This section describes disabled children’s experiences of participation, learning, and wellbeing at ECE and what their parents said about their experiences.

How we gathered information

To understand disabled children’s experiences and outcomes, we asked parents and whānau about their child’s experiences in ECE. In both an online survey and a set of interview questions we asked about their child’s:

- participation

- learning

- wellbeing and sense of belonging.

We also visited a selection of ECE centres and observed how these children were supported. More details about the survey and interviews are set out in Appendix 1.

What we found: An overview

Disabled children are still experiencing exclusion. A significant number of parents have been discouraged from enrolling their disabled child. Some parents have been asked to keep their disabled child home when their peers are undertaking specific activities, such as excursions.

It is unclear how well disabled children’s learning is progressing. There is a lack of information, both at a service and system level, about how well disabled children are learning and progressing. Assessment tends to show what children have done, rather than what they have learnt.

Disabled children enjoy ECE and feel they belong. The belonging, safety and comfort of most disabled children is effectively supported at the service they are attending, and most children enjoy attending.

-

Participation

This section shares what ERO learnt about:

a) disabled children’s experiences enrolling in an ECE service

b) their inclusion once enrolled.

a) Enrolment

Disabled children are being excluded from enrolling in ECE services

ECE services should not discriminate against children with additional learning needs (including disabled children) in their enrolment policies and practices.[18] Despite this, we heard from many parents that not all centres are welcoming of them and their child. They have been discouraged from enrolling, and in many cases, refused enrolment. Over one in four parents we surveyed (26 percent) have been discouraged from enrolling their disabled child at one or more services (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Discouraged from enrolling in a service: Parents survey

When we spoke to parents about their enrolment experiences, we heard they often have to approach a large number of services before they are able to find one that will enrol their child. One parent told us they had either been refused or had limits put on their child’s inclusion from an estimated 30 ECE services.

She explained that, even after going through a long enrolment process with her eldest child who also has additional learning needs, she still had significant challenges with her youngest: