Related information

Read Online

Summary

To support greater student engagement and achievement, from the beginning of Term 2, 2024, school boards and kura were required to ensure that students do not use cell phones during the school day. ERO’s review of the implementation of this policy shows there have been positive impacts to students’ focus and achievement as well as a reduction in bullying. This summary provides an overview of the findings and recommendations of ERO’s full report Do not disturb: A review of removing cell phones from New Zealand’s classrooms.

To support greater student engagement and achievement, from the beginning of Term 2, 2024, school boards and kura were required to ensure that students do not use cell phones during the school day. ERO’s review of the implementation of this policy shows there have been positive impacts to students’ focus and achievement as well as a reduction in bullying. This summary provides an overview of the findings and recommendations of ERO’s full report Do not disturb: A review of removing cell phones from New Zealand’s classrooms.

Managing student cell phone use is one way New Zealand can address some of the key challenges facing young people. It can support better learning, improve behaviour, and reduce the risks associated with social media. To help students stay focused on learning, a new policy was introduced in Term 2, 2024 – students are required to keep their phones away during the school day. School boards and kura are responsible for putting this into practice. This summary shares what’s working well, what the impact has been, and explores how we can continue to build on this progress.

Managing student cell phone use is one way New Zealand can address some of the key challenges facing young people. It can support better learning, improve behaviour, and reduce the risks associated with social media. To help students stay focused on learning, a new policy was introduced in Term 2, 2024 – students are required to keep their phones away during the school day. School boards and kura are responsible for putting this into practice. This summary shares what’s working well, what the impact has been, and explores how we can continue to build on this progress.

ERO found that nearly all schools have adopted the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy, although only around half of secondary students are consistently following the rules. Despite this, the policy is already making a difference – students are showing greater focus, academic performance is improving, and bullying is decreasing. Schools that consistently enforce their rules with firm consequences, and have strong support from teachers, students, and families, are seeing even greater benefits. In these schools, students are not only more likely to follow the rules, but also show more improvement in achievement, wellbeing, and behaviour.

ERO found that nearly all schools have adopted the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy, although only around half of secondary students are consistently following the rules. Despite this, the policy is already making a difference – students are showing greater focus, academic performance is improving, and bullying is decreasing. Schools that consistently enforce their rules with firm consequences, and have strong support from teachers, students, and families, are seeing even greater benefits. In these schools, students are not only more likely to follow the rules, but also show more improvement in achievement, wellbeing, and behaviour.

Why does cell phone use in classrooms matter?

Restricting student cell phone use in schools has the potential to significantly enhance both academic achievement and wellbeing. It can lead to improved concentration, better behaviour, and higher levels of achievement. It also helps mitigate risks associated with excessive social media use, exposure to harmful content, and cyberbullying. In response to these concerns, many jurisdictions – including New Zealand – have introduced policies to limit or completely ban student phone use during school hours.

What requirements have been put in place?

The Government prohibited student use of cell phones during the school day from Term 2, 2024. This requirement applies to all students enrolled in state and state-integrated schools, with some exceptions. School boards and kura are responsible for putting the rules in place

and enforcing them.

Restricting student cell phone use in schools has the potential to significantly enhance both academic achievement and wellbeing. It can lead to improved concentration, better behaviour, and higher levels of achievement. It also helps mitigate risks associated with excessive social media use, exposure to harmful content, and cyberbullying. In response to these concerns, many jurisdictions – including New Zealand – have introduced policies to limit or completely ban student phone use during school hours.

What requirements have been put in place?

The Government prohibited student use of cell phones during the school day from Term 2, 2024. This requirement applies to all students enrolled in state and state-integrated schools, with some exceptions. School boards and kura are responsible for putting the rules in place

and enforcing them.

Finding 1: Encouragingly, nearly all schools have a ‘Phones Away for the Day’ rule.

- We consistently heard from board members, school leaders, teachers, students, and parents and whānau, that rules had been put in place at their schools

- Over half (54 percent) of secondary schools have made changes to their rules compared to just five percent of primary2 schools.

“So starting from Term 1, they were quite lenient at first because they wanted us to settle into not using this device that you’ve had all this time, especially for senior students. And then from Term 2 and Term 3, if they saw a phone, it was instantly taken away.”

- SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENT

- We consistently heard from board members, school leaders, teachers, students, and parents and whānau, that rules had been put in place at their schools

- Over half (54 percent) of secondary schools have made changes to their rules compared to just five percent of primary2 schools.

“So starting from Term 1, they were quite lenient at first because they wanted us to settle into not using this device that you’ve had all this time, especially for senior students. And then from Term 2 and Term 3, if they saw a phone, it was instantly taken away.”

- SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENT

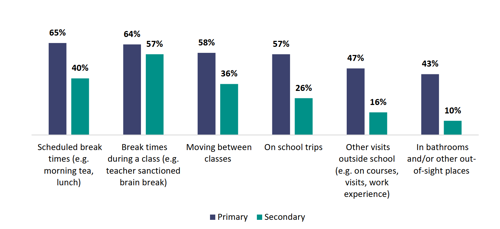

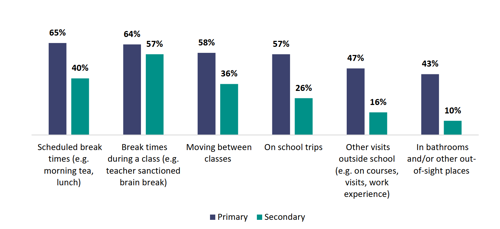

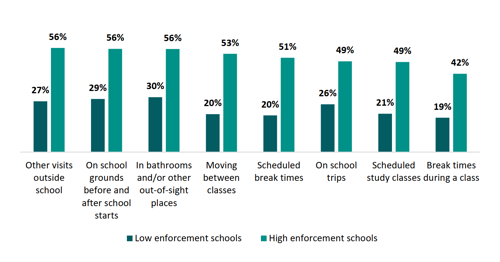

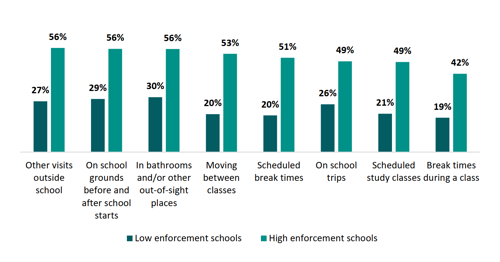

Finding 2: Nearly all schools have rules prohibiting phone use at school at all times of the day, but there are large variations in when and where teachers enforce the rules.

- Over nine in ten (94 percent) schools ban phone use during the day and most (95 percent) have the same rules across year levels.

- Enforcement happens in class but not so much between classes – 57 percent of teachers report they aren’t strictly enforcing the rules during scheduled breaks (e.g., morning tea), and 61 percent report they aren’t when students move between classes.

Figure 1: Percentage of teachers reporting when and where they aren’t strictly monitoring and enforcing phone rules

- Over nine in ten (94 percent) schools ban phone use during the day and most (95 percent) have the same rules across year levels.

- Enforcement happens in class but not so much between classes – 57 percent of teachers report they aren’t strictly enforcing the rules during scheduled breaks (e.g., morning tea), and 61 percent report they aren’t when students move between classes.

Figure 1: Percentage of teachers reporting when and where they aren’t strictly monitoring and enforcing phone rules

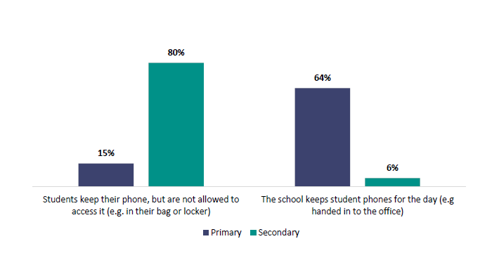

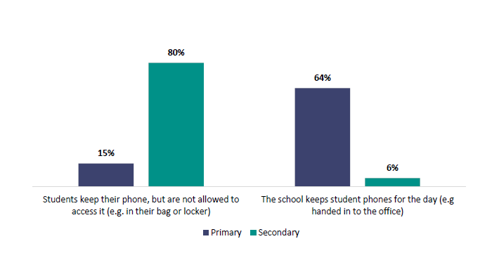

Finding 3: What ‘Phones Away for the Day’ looks like is very different between primary and secondary schools. Secondary schools let students keep their phones with them more, and monitor and enforce less. Primary schools store students’ phones more and enforce more.

- Most secondary schools let students keep their phones during the school day – eight in ten (80 percent) do, compared to about one in seven (15 percent) primary schools.

- Almost two-thirds (64 percent) of primary schools store students’ phones compared to just six percent of secondary schools. Primary school leaders told us that it was relatively easy for them to deal with collecting student phones because they have smaller school rolls and

fewer students with phones. This also meant that they could monitor student phone use more easily and respond to issues promptly.

“So being a primary school, we don’t allow them at all. We have a lock box that students are required to put their phones into in the morning when they arrive at school. And they can collect them at the end of the day.”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL LEADER

Figure 2: Percentage of leaders reporting where students’ phones should be during the school day, by school type

- Secondary teachers are also less strict – during scheduled break times, only four in ten (40 percent) secondary teachers strictly monitor phone use, compared to nearly two-thirds (65 percent) of primary teachers.

“I’ve got over 100 teachers so it can be hard to ensure consistency. I’d say there’s real consistency INSIDE the classroom, but OUTSIDE the classroom there’s only 10 to 12 of my people on duty at any one time.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL LEADER

Figure 3: Percentage of teachers reporting when and where they monitor and enforce phone rules ‘to a great extent’, by school type

- Most secondary schools let students keep their phones during the school day – eight in ten (80 percent) do, compared to about one in seven (15 percent) primary schools.

- Almost two-thirds (64 percent) of primary schools store students’ phones compared to just six percent of secondary schools. Primary school leaders told us that it was relatively easy for them to deal with collecting student phones because they have smaller school rolls and

fewer students with phones. This also meant that they could monitor student phone use more easily and respond to issues promptly.

“So being a primary school, we don’t allow them at all. We have a lock box that students are required to put their phones into in the morning when they arrive at school. And they can collect them at the end of the day.”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL LEADER

Figure 2: Percentage of leaders reporting where students’ phones should be during the school day, by school type

- Secondary teachers are also less strict – during scheduled break times, only four in ten (40 percent) secondary teachers strictly monitor phone use, compared to nearly two-thirds (65 percent) of primary teachers.

“I’ve got over 100 teachers so it can be hard to ensure consistency. I’d say there’s real consistency INSIDE the classroom, but OUTSIDE the classroom there’s only 10 to 12 of my people on duty at any one time.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL LEADER

Figure 3: Percentage of teachers reporting when and where they monitor and enforce phone rules ‘to a great extent’, by school type

Finding 4: Both primary and secondary schools in low socio-economic communities are less strict in enforcing the rules, but in primary they store student phones more.

- In primary, more schools in low socio-economic communities collect student phones – 86 percent do so compared to 60 percent in higher socio-economic communities.

- But enforcement is weaker across schools in lower socio-economic communities – for example 52 percent enforce phone rules during scheduled breaks, compared to 64 percent in schools in higher socio-economic communities. This may be due to limited resources,

stronger reliance on phones for family connection, or a focus on maintaining relationships over strict rule compliance.

- In primary, more schools in low socio-economic communities collect student phones – 86 percent do so compared to 60 percent in higher socio-economic communities.

- But enforcement is weaker across schools in lower socio-economic communities – for example 52 percent enforce phone rules during scheduled breaks, compared to 64 percent in schools in higher socio-economic communities. This may be due to limited resources,

stronger reliance on phones for family connection, or a focus on maintaining relationships over strict rule compliance.

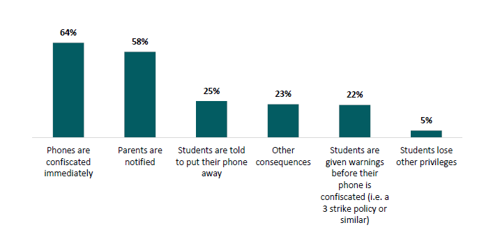

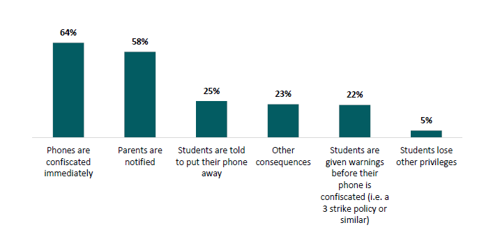

Finding 5: When students break the phone rules, schools most commonly confiscate student phones and notify parents.

- Over six in ten (64 percent) schools immediately confiscate phones when they are used inappropriately and over half (58 percent) notify parents when students break the phone use rules.

Figure 4: Percentage of leaders reporting how schools respond when students break phone rules

- Secondary schools are twice as likely to give warnings before they confiscate phones (33 percent) compared to primary schools (16 percent).

- Leaders, teachers, and students often described having a series of stepped consequences such as warnings, confiscation of the phone, then detention (in secondary schools), followed by stand-downs for persistent rule-breaking.

“We have a step system in place that escalates based on how many times a student has had their phone confiscated (warning – detentions – whānau meetings etc.).”

- LEADER

- Over six in ten (64 percent) schools immediately confiscate phones when they are used inappropriately and over half (58 percent) notify parents when students break the phone use rules.

Figure 4: Percentage of leaders reporting how schools respond when students break phone rules

- Secondary schools are twice as likely to give warnings before they confiscate phones (33 percent) compared to primary schools (16 percent).

- Leaders, teachers, and students often described having a series of stepped consequences such as warnings, confiscation of the phone, then detention (in secondary schools), followed by stand-downs for persistent rule-breaking.

“We have a step system in place that escalates based on how many times a student has had their phone confiscated (warning – detentions – whānau meetings etc.).”

- LEADER

Finding 6: While most secondary schools allow phone exemptions for health, disability, and learning needs, some students may not be getting the support they need. A quarter of schools do not offer exemptions for learning support reasons, and over a quarter of teachers are unaware of their school’s exemption policies.

- Regulations require schools to provide phone exemptions for disabled students and students with health and learning support needs. We heard from board members across all school types that they typically delegate decisions about the use of student exemptions to their principals in practice.

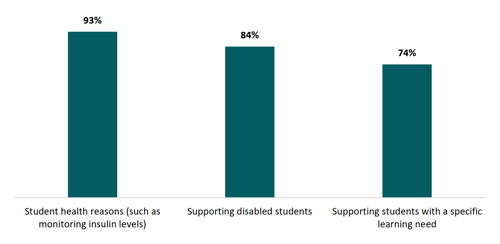

- Most secondary schools allow health exemptions (93 percent) and for disabled students (84 percent), but a quarter (26 percent) do not offer exemptions for students with specific learning needs.

Figure 5: Percentage of secondary leaders reporting they allow exemptions for health, disability, or specific learning needs

- Even where exemptions are available, over a quarter (26 percent) of teachers are unaware of their school’s exemption policies or which students they apply to. We also heard that the variety of exemptions can be difficult to manage, especially in large settings where tracking

exemptions can be difficult.

“…We have around 90 students on our exemption list. Because that list is so large, it’s really difficult for teachers to track who has the exemption and who doesn’t... So you might get to know that if it’s a regular class. But if there’s a reliever in there or if the kids are moving between one venue and another on a large campus and a teacher

walks past, it’s difficult.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL LEADER

- Regulations require schools to provide phone exemptions for disabled students and students with health and learning support needs. We heard from board members across all school types that they typically delegate decisions about the use of student exemptions to their principals in practice.

- Most secondary schools allow health exemptions (93 percent) and for disabled students (84 percent), but a quarter (26 percent) do not offer exemptions for students with specific learning needs.

Figure 5: Percentage of secondary leaders reporting they allow exemptions for health, disability, or specific learning needs

- Even where exemptions are available, over a quarter (26 percent) of teachers are unaware of their school’s exemption policies or which students they apply to. We also heard that the variety of exemptions can be difficult to manage, especially in large settings where tracking

exemptions can be difficult.

“…We have around 90 students on our exemption list. Because that list is so large, it’s really difficult for teachers to track who has the exemption and who doesn’t... So you might get to know that if it’s a regular class. But if there’s a reliever in there or if the kids are moving between one venue and another on a large campus and a teacher

walks past, it’s difficult.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL LEADER

Finding 7: Only around half of secondary students consistently follow their school’s phone rules. Compliance is also lower in schools in lower socio-economic communities, and during breaks and in unsupervised areas.

How compliant are students?

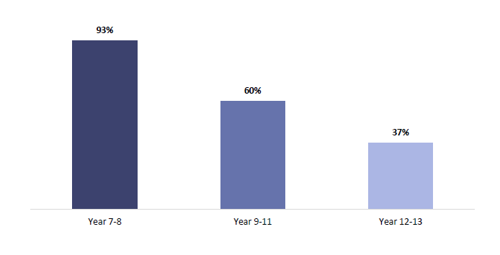

- Over nine in ten (93 percent) Year 7-8 students follow their school’s phone rules, but compliance drops as students get older, with six in ten (60 percent) Year 9-11 students and just under four in ten (37 percent) Year 12-13 students following the rules. Overall, just over half (53 percent) of secondary students (year 9-13) say they never use their phone in class.

Figure 6: Percentage of students who report they ‘never’ use their phone in class, by year level

- Over one in three students still use their phone during lunch or morning tea breaks (38 percent), in bathrooms or other out-of-sight places (36 percent), or at break times during class (34 percent).

“The students are sneaky, they use their phones all the time, like in bathrooms and in class time, but the teachers never catch them.”

- STUDENT

- Compliance is also lower in schools in low socio-economic communities. This may be linked to lower enforcement of the rules in schools in low socio-economic communities, or because more of these students break the rules to stay connected with their family.

How compliant are students?

- Over nine in ten (93 percent) Year 7-8 students follow their school’s phone rules, but compliance drops as students get older, with six in ten (60 percent) Year 9-11 students and just under four in ten (37 percent) Year 12-13 students following the rules. Overall, just over half (53 percent) of secondary students (year 9-13) say they never use their phone in class.

Figure 6: Percentage of students who report they ‘never’ use their phone in class, by year level

- Over one in three students still use their phone during lunch or morning tea breaks (38 percent), in bathrooms or other out-of-sight places (36 percent), or at break times during class (34 percent).

“The students are sneaky, they use their phones all the time, like in bathrooms and in class time, but the teachers never catch them.”

- STUDENT

- Compliance is also lower in schools in low socio-economic communities. This may be linked to lower enforcement of the rules in schools in low socio-economic communities, or because more of these students break the rules to stay connected with their family.

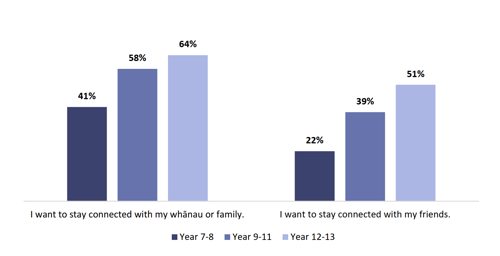

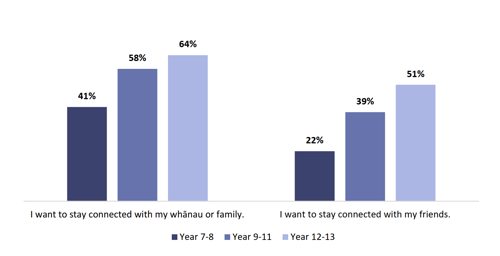

Finding 8: The top reason students break the rules is to stay connected with their family – especially older students and those from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

- Staying connected with family is the most common reason students break the rules – over half (54 percent) of rule-breakers say this is why they do it.

- This behaviour is more prevalent in schools in lower socio-economic communities, where 57 percent of rule-breakers cite staying connected with family as their reason, compared to 46 percent in schools in higher socio-economic communities.

- Older students who break the rules are more likely to do so to stay connected with family: over six in ten (64 percent) of Year 12-13 students who break the rules do so, compared to just two in ten (41 percent) of Year 7-8 students who break the rules.

Figure 7: Percentage of students who break the rules because they want to stay connected with their family, by year level

- Staying connected with family is the most common reason students break the rules – over half (54 percent) of rule-breakers say this is why they do it.

- This behaviour is more prevalent in schools in lower socio-economic communities, where 57 percent of rule-breakers cite staying connected with family as their reason, compared to 46 percent in schools in higher socio-economic communities.

- Older students who break the rules are more likely to do so to stay connected with family: over six in ten (64 percent) of Year 12-13 students who break the rules do so, compared to just two in ten (41 percent) of Year 7-8 students who break the rules.

Figure 7: Percentage of students who break the rules because they want to stay connected with their family, by year level

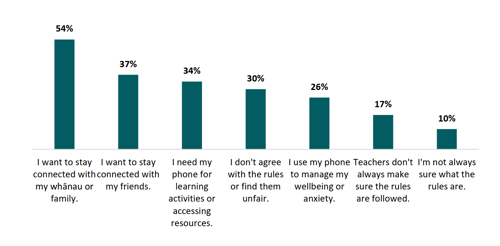

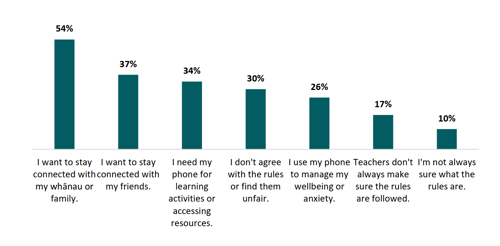

Finding 9: Students also break phone rules to connect with friends, for learning, or because they personally oppose the rules.

- Just under four in ten (37 percent) students who do not always comply with phone rules say it’s because they want to connect with friends, and a similar number (34 percent) say it’s because they need their phone for learning.

- Three in ten (30 percent) of the students who use their phone at school break the rules because they reject the rules as unfair or disagree with them. This reasoning increases with age and is more common among students in schools in lower socio-economic communities.

Figure 8: Reasons why students who break the rules do not always comply

- Just under four in ten (37 percent) students who do not always comply with phone rules say it’s because they want to connect with friends, and a similar number (34 percent) say it’s because they need their phone for learning.

- Three in ten (30 percent) of the students who use their phone at school break the rules because they reject the rules as unfair or disagree with them. This reasoning increases with age and is more common among students in schools in lower socio-economic communities.

Figure 8: Reasons why students who break the rules do not always comply

Finding 10: Parent support matters – when parents resist phone rules, students are more likely to break them.

- Most primary (89 percent) and secondary (86 percent) teachers say parent support helps them implement phone rules.

- However, in schools where parent resistance is a problem, secondary students are almost half as likely (0.6 times) to follow the rules.

- We heard that while some parents and whānau understand prohibiting phone use can reduce distractions, other parents and whānau expect to be able to reach their children, even during class time. This contact with family contributes to rule-breaking.

“…Half the time you see a kid walking across school on their phone and they’re like, ‘Oh, it’s my mum.’”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHER

- Most primary (89 percent) and secondary (86 percent) teachers say parent support helps them implement phone rules.

- However, in schools where parent resistance is a problem, secondary students are almost half as likely (0.6 times) to follow the rules.

- We heard that while some parents and whānau understand prohibiting phone use can reduce distractions, other parents and whānau expect to be able to reach their children, even during class time. This contact with family contributes to rule-breaking.

“…Half the time you see a kid walking across school on their phone and they’re like, ‘Oh, it’s my mum.’”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHER

Finding 11: There is encouraging evidence that secondary students are more focused on learning as a result of prohibiting phone use at school.

What is the impact of ‘Phones Away for the Day’?

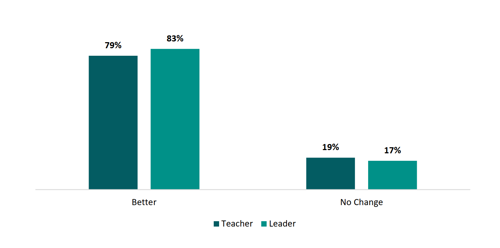

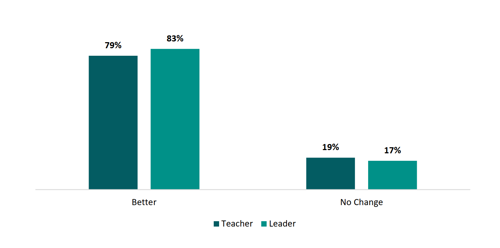

- Around eight in ten secondary leaders (83 percent) and teachers (79 percent) report prohibiting phone use at school has improved their students’ ability to focus on schoolwork.

- We heard that the policy has supported some students in developing stronger connections with their teachers and building more effective learning habits.

“…I love using my phone. It has everything on it. It’s efficient. But with this ban, it taught me some restraint and I would say that I am able to focus better because I can’t use it. I got to do my work now. It just taught me how to prioritise things better.”

- SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENT

Figure 9: Percentage of secondary teachers and leaders who say restricting phone use at school has made students’ ability to focus on schoolwork better or there was no change

What is the impact of ‘Phones Away for the Day’?

- Around eight in ten secondary leaders (83 percent) and teachers (79 percent) report prohibiting phone use at school has improved their students’ ability to focus on schoolwork.

- We heard that the policy has supported some students in developing stronger connections with their teachers and building more effective learning habits.

“…I love using my phone. It has everything on it. It’s efficient. But with this ban, it taught me some restraint and I would say that I am able to focus better because I can’t use it. I got to do my work now. It just taught me how to prioritise things better.”

- SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENT

Figure 9: Percentage of secondary teachers and leaders who say restricting phone use at school has made students’ ability to focus on schoolwork better or there was no change

Finding 12: Importantly, secondary teachers report achievement has improved since phone rules were put in place.

- The increased ability to focus in class appears to have contributed to learning, with around six in ten secondary teachers (61 percent) and leaders (58 percent) reporting student achievement has improved.

“I think so far [the rules are] positive. There’s no more of me looking at my phone in my pocket no more, neglecting my learning in the middle of classes.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENT

- The increased ability to focus in class appears to have contributed to learning, with around six in ten secondary teachers (61 percent) and leaders (58 percent) reporting student achievement has improved.

“I think so far [the rules are] positive. There’s no more of me looking at my phone in my pocket no more, neglecting my learning in the middle of classes.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENT

Finding 13: Behaviour and bullying have improved, meaning secondary teachers can spend more time teaching.

- Over three-quarters of secondary teachers (77 percent) and leaders (78 percent) say restricting cell phone use has improved student behaviour in the classroom. Over two-thirds (69 percent) of secondary leaders say that bullying has decreased. This means that teachers can spend more time on teaching and learning.

- Teachers, leaders, and board members also told us they have seen improvements in social interactions with the absence of phones during breaks.

“This has been one of the best policies the school could have implemented. The cyber bullying was at an all-time high before the policy was put in place. Now students talk to each other, and our students play.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL LEADER

Figure 10: Percentage of secondary teachers and leaders who say restricting phone use at school has reduced the frequency of bullying and improved behaviour in the classroom

- Over three-quarters of secondary teachers (77 percent) and leaders (78 percent) say restricting cell phone use has improved student behaviour in the classroom. Over two-thirds (69 percent) of secondary leaders say that bullying has decreased. This means that teachers can spend more time on teaching and learning.

- Teachers, leaders, and board members also told us they have seen improvements in social interactions with the absence of phones during breaks.

“This has been one of the best policies the school could have implemented. The cyber bullying was at an all-time high before the policy was put in place. Now students talk to each other, and our students play.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL LEADER

Figure 10: Percentage of secondary teachers and leaders who say restricting phone use at school has reduced the frequency of bullying and improved behaviour in the classroom

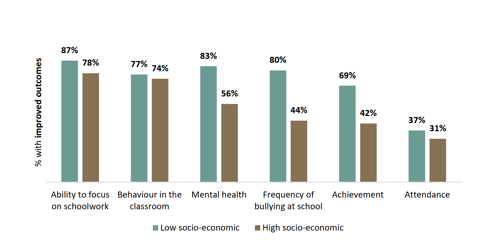

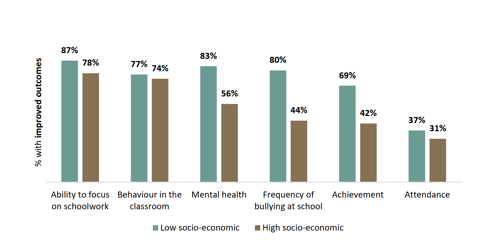

Finding 14: Encouragingly, more secondary schools in lower socio-economic communities have improved outcomes.

- Even though students in schools in low socio-economic communities comply less with the rules, they have seen bigger shifts in their outcomes than their peers in high socio-economic communities.

- Almost seven in ten (69 percent) leaders in secondary schools in low socio-economic communities said achievement improved, compared to four in ten (42 percent) in high socioeconomic communities. The same trend showed up in bullying (80 percent of schools in low socio-economic communities compared to 44 percent in high socio-economic communities), and students’ mental health (83 percent in schools in low socio-economic communities compared to 56 percent in high socio-economic communities).

- The bigger gains could be because, according to PISA data, students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds experience greater distractions from digital devices, and therefore have more room for improvement when those distractions are reduced or better managed.

Figure 11: Percentage of secondary leaders who say restricting phone use at school has improved student outcomes, by socio-economic status

- Even though students in schools in low socio-economic communities comply less with the rules, they have seen bigger shifts in their outcomes than their peers in high socio-economic communities.

- Almost seven in ten (69 percent) leaders in secondary schools in low socio-economic communities said achievement improved, compared to four in ten (42 percent) in high socioeconomic communities. The same trend showed up in bullying (80 percent of schools in low socio-economic communities compared to 44 percent in high socio-economic communities), and students’ mental health (83 percent in schools in low socio-economic communities compared to 56 percent in high socio-economic communities).

- The bigger gains could be because, according to PISA data, students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds experience greater distractions from digital devices, and therefore have more room for improvement when those distractions are reduced or better managed.

Figure 11: Percentage of secondary leaders who say restricting phone use at school has improved student outcomes, by socio-economic status

Finding 15: Pacific students benefit the most. But students who are disabled or have learning needs4 experience some negative effects.

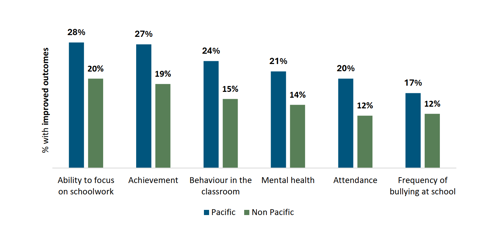

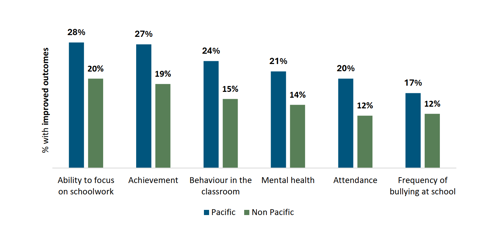

- Pacific students report greater improvements across behaviour, attendance, focus, achievement, bullying, and mental health. ERO’s recent report on attitudes to attendance found that Pacific students have shown some of the most positive attitudes towards being present and focused in school, and that this increased between 2022 and 2025.

Figure 12: Percentage of students who say restricting phone use at school has improved their outcomes, by Pacific identity

- In contrast, students that identify as disabled or having learning needs report worse outcomes – around a quarter reported worse experiences in areas like mental health (28 percent), bullying (24 percent), and focus on schoolwork (23 percent). This may be linked to the finding that not all schools offer exemptions for these students, and teachers are not always aware of the exemption rules or who they apply to.

“Due to disability being in the spectrum, my son needs his phone for anxiety support. And when he can’t use the phone, his anxiety has flared up. This is a factor for his attendance to school. School does not help with this accommodation at all.”

- PARENT/WHĀNAU

- Pacific students report greater improvements across behaviour, attendance, focus, achievement, bullying, and mental health. ERO’s recent report on attitudes to attendance found that Pacific students have shown some of the most positive attitudes towards being present and focused in school, and that this increased between 2022 and 2025.

Figure 12: Percentage of students who say restricting phone use at school has improved their outcomes, by Pacific identity

- In contrast, students that identify as disabled or having learning needs report worse outcomes – around a quarter reported worse experiences in areas like mental health (28 percent), bullying (24 percent), and focus on schoolwork (23 percent). This may be linked to the finding that not all schools offer exemptions for these students, and teachers are not always aware of the exemption rules or who they apply to.

“Due to disability being in the spectrum, my son needs his phone for anxiety support. And when he can’t use the phone, his anxiety has flared up. This is a factor for his attendance to school. School does not help with this accommodation at all.”

- PARENT/WHĀNAU

Finding 16: Six in ten (59 percent) parents have not changed how they communicate with their child while at school, and some remain worried about not being able to connect with their child during the day.

- Worryingly, almost six in ten (59 percent) parents and whānau report they have not adjusted how they communicate with their child while at school, which aligns with how many parents are still messaging their child during the day.

- Still, nearly a third (29 percent) of all parents and whānau remain concerned about not being able to contact their child during the day. Parents and whānau expressed that they were concerned because they were unable to provide support to students when issues arose at school.

“When she didn’t have a phone I struggled with comms, organising pickups, organised throughout the day. If she posted all [sport] trainings on Facebook page it would be fine.”

- PARENT/WHĀNAU

- Worryingly, almost six in ten (59 percent) parents and whānau report they have not adjusted how they communicate with their child while at school, which aligns with how many parents are still messaging their child during the day.

- Still, nearly a third (29 percent) of all parents and whānau remain concerned about not being able to contact their child during the day. Parents and whānau expressed that they were concerned because they were unable to provide support to students when issues arose at school.

“When she didn’t have a phone I struggled with comms, organising pickups, organised throughout the day. If she posted all [sport] trainings on Facebook page it would be fine.”

- PARENT/WHĀNAU

Finding 17: Clear, consistent rules and strong, consistent enforcement drives compliance.

What works and what gets in the way of ‘Phones Away for the Day’?

- Primary students are more than twice as likely (2.2 times) to be compliant when rules are consistent across year levels.

- Secondary teachers and leaders are over one and a half times as likely (1.6 times) to report a high level of student compliance when students understand the purpose of the rules.

- When rules are consistently enforced within a school, compliance increases. Secondary teachers and leaders are twice as likely (2.0 times) to say students follow the rules consistently when rules are enforced to a great extent.

“Some teachers let students use their phones when the students don’t have [devices]. This is very frustrating for the teachers who tell students they can’t use their phones as it creates a situation where teachers are pitted against each other. Some teachers are “nice”, “cool” or “chill” and let student use their phones, makes those that don’t let them seem too strict.”

- TEACHER

Figure 13: Percentage of schools where senior secondary students consistently follow the rules, in low and high enforcement schools

What works and what gets in the way of ‘Phones Away for the Day’?

- Primary students are more than twice as likely (2.2 times) to be compliant when rules are consistent across year levels.

- Secondary teachers and leaders are over one and a half times as likely (1.6 times) to report a high level of student compliance when students understand the purpose of the rules.

- When rules are consistently enforced within a school, compliance increases. Secondary teachers and leaders are twice as likely (2.0 times) to say students follow the rules consistently when rules are enforced to a great extent.

“Some teachers let students use their phones when the students don’t have [devices]. This is very frustrating for the teachers who tell students they can’t use their phones as it creates a situation where teachers are pitted against each other. Some teachers are “nice”, “cool” or “chill” and let student use their phones, makes those that don’t let them seem too strict.”

- TEACHER

Figure 13: Percentage of schools where senior secondary students consistently follow the rules, in low and high enforcement schools

Finding 19: Tougher consequences like parent notification and confiscating phones increases compliance.

- Parent notification increases the likelihood (1.5 times) of secondary students’ compliance.

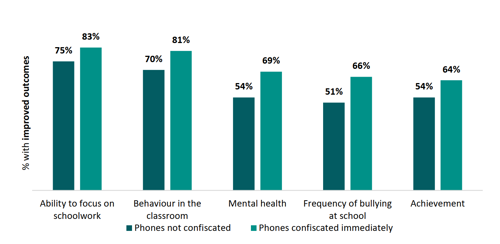

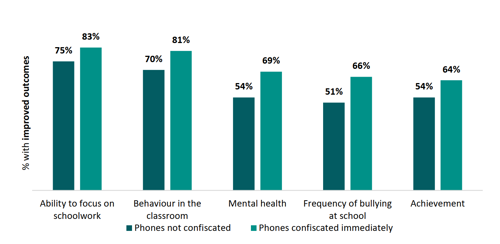

- Confiscating phones means schools are around twice as likely to report that behaviour (2.0 times), focus (2.1 times) and achievement (1.9 times) have improved.

“Parents must drive to school to collect the phone (15km from town) phones are not given back to students unless collected by a parent.”

- LEADER

Figure 15: Percentage of secondary schools that report outcomes have improved by whether phones are confiscated immediately in response to rule-breaking

- Parent notification increases the likelihood (1.5 times) of secondary students’ compliance.

- Confiscating phones means schools are around twice as likely to report that behaviour (2.0 times), focus (2.1 times) and achievement (1.9 times) have improved.

“Parents must drive to school to collect the phone (15km from town) phones are not given back to students unless collected by a parent.”

- LEADER

Figure 15: Percentage of secondary schools that report outcomes have improved by whether phones are confiscated immediately in response to rule-breaking

Finding 20: Simply telling students to put phones away reduces compliance.

- A softer approach to rule-breaking appears to be less effective for senior students and can make it worse. Regardless of other consequences used, simply telling Year 12-13 students to put phones away halves (0.5 times) their compliance.

- We heard how some students wilfully rebel against the rule, just because they were told to follow it. Whereas, ensuring students understand the rules makes a difference and was reported as helpful in implementing the rules by nine out of ten (87 percent) primary schools and almost eight out of ten (78 percent) secondary schools.

“…Like an instinct to always like reverse psychology, everything that adults tell you to do. So it’s like if they suddenly banned like bananas and we’re really [like] bananas. Everyone would be eating bananas secretly, you know? Yeah, because they’re teenagers.”

- SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENT

- A softer approach to rule-breaking appears to be less effective for senior students and can make it worse. Regardless of other consequences used, simply telling Year 12-13 students to put phones away halves (0.5 times) their compliance.

- We heard how some students wilfully rebel against the rule, just because they were told to follow it. Whereas, ensuring students understand the rules makes a difference and was reported as helpful in implementing the rules by nine out of ten (87 percent) primary schools and almost eight out of ten (78 percent) secondary schools.

“…Like an instinct to always like reverse psychology, everything that adults tell you to do. So it’s like if they suddenly banned like bananas and we’re really [like] bananas. Everyone would be eating bananas secretly, you know? Yeah, because they’re teenagers.”

- SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENT

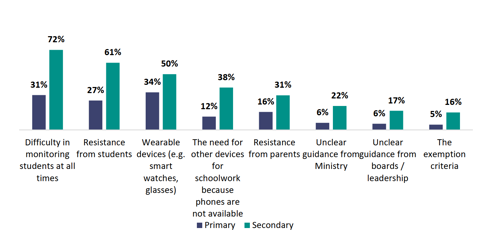

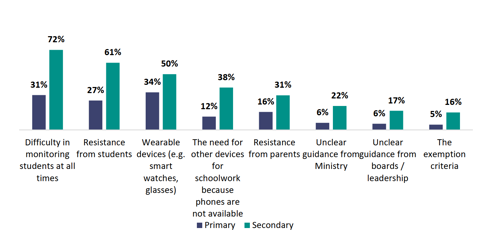

Finding 21: Implementing phone rules is easier now there is a law, but challenges like student and parent resistance, wearable devices, and inconsistent exemption use remain in secondary schools.

- In both primary and secondary schools, leaders, teachers, and key informants told us that the law has helped schools enforce phone rules, even if they already had phone rules, because it helped them respond to parent and student concerns and resistance.

“Our parents are funny about it. Especially mid- and- post Covid, there was a lot of resistance to anybody being told to do anything or to comply with anything. So this little piece of legislation or whatever we call it was an absolute blessing for us because it took it out of my hands.”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL LEADER

- However, we also heard that barriers still exist. Most secondary teachers say that the difficulty in having to monitor students and enforce the rules at all times (72 percent), student resistance (61 percent), and wearable devices (50 percent) make it difficult to implement phone rules. Three in ten (31 percent) secondary teachers say parent resistance

is also a barrier.

“It’s incredibly hard to enforce a policy across a huge campus. It’s not possible. There’s not enough staff members to do it. There’s not enough places. And it’s speaking to the policy itself, which is when you’re supposed to see the phone and then take it, log it, and then take it back to the office. It’s not, you know, logistically possible to do.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHER

“…We consider earbuds or headphones to be a natural extension of the phone, because not too many of us work without them now. But we haven’t done anything in terms of smartwatches.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL LEADER

“…It was like playing whack-a-mole, you know? Whichever service you turned off, there was something else turned on.”

- BOARD MEMBER

- There is also inconsistent understanding of rules, particularly around exemptions. One in six (16 percent) secondary teachers find the exemption criteria to be a barrier to implementing the rules.

Figure 16: Percentage of teachers reporting what makes it difficult to implement ‘Phones Away for the Day’, by school type

- In both primary and secondary schools, leaders, teachers, and key informants told us that the law has helped schools enforce phone rules, even if they already had phone rules, because it helped them respond to parent and student concerns and resistance.

“Our parents are funny about it. Especially mid- and- post Covid, there was a lot of resistance to anybody being told to do anything or to comply with anything. So this little piece of legislation or whatever we call it was an absolute blessing for us because it took it out of my hands.”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL LEADER

- However, we also heard that barriers still exist. Most secondary teachers say that the difficulty in having to monitor students and enforce the rules at all times (72 percent), student resistance (61 percent), and wearable devices (50 percent) make it difficult to implement phone rules. Three in ten (31 percent) secondary teachers say parent resistance

is also a barrier.

“It’s incredibly hard to enforce a policy across a huge campus. It’s not possible. There’s not enough staff members to do it. There’s not enough places. And it’s speaking to the policy itself, which is when you’re supposed to see the phone and then take it, log it, and then take it back to the office. It’s not, you know, logistically possible to do.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHER

“…We consider earbuds or headphones to be a natural extension of the phone, because not too many of us work without them now. But we haven’t done anything in terms of smartwatches.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL LEADER

“…It was like playing whack-a-mole, you know? Whichever service you turned off, there was something else turned on.”

- BOARD MEMBER

- There is also inconsistent understanding of rules, particularly around exemptions. One in six (16 percent) secondary teachers find the exemption criteria to be a barrier to implementing the rules.

Figure 16: Percentage of teachers reporting what makes it difficult to implement ‘Phones Away for the Day’, by school type

What have we learnt?

Lesson 1: National action to limit digital distractions in schools can improve students’ achievement and wellbeing (and help teachers teach)

- Nationwide bans can ensure action in all schools. Bans can be implemented in all schools nationally, across all school types.

- Limiting digital distractions can benefit both learning and mental health. These limits can improve student achievement, focus, behaviour, social connection, and mental health.

- Removing distractions from schools can make the biggest difference to students facing the biggest challenges. Lower socio-economic communities can see greater improvements in outcomes.

Lesson 2: There are clear actions schools can take that make the biggest difference in ensuring compliance with national rules

- Clear and consistent rules with firm consequences around phone use are essential. Consistent rules across year levels and firm consequences such as notifying parents and confiscating phones increase compliance.

- Teachers need to understand, support, and enforce the rules. When teachers support, monitor, and enforce rules around device use, student outcomes improve.

- It is key to get students and parents and whānau on board. When students and parents and whānau understand school policy, compliance and outcomes improve.

- Tougher enforcement actions are more effective with secondary students. Notifying parents and confiscating phones can increase compliance, while simply telling students to put their phones away can reduce compliance.

Lesson 3: National action on cell phones helps, but is not enough alone to remove digital distractions and the potential harm of social media

- Banning cell phones alone does not eliminate digital distractions. Half of secondary schools report that wearable devices make it difficult to enforce phone restrictions, and many schools consistently note that access to other devices, such as laptops, also poses a significant challenge.

- Stronger action may be required to properly manage risks from access to devices and social media. While the phone ban has reduced harm linked to social media – such as bullying – and improved students’ mental health, students can still access social media through other means.

Lesson 4: Parents play a key role and need to understand and back schools’ actions to remove digital distractions

- Parents do not always understand and support school rules, and this needs to be addressed. While parents support the intent of limiting digital distractions in the classroom, they have various concerns and do not always support the school rules.

- Parents have an important role to play, and when they are not supportive of school rules, student compliance is compromised. Parent resistance can be a barrier to student compliance.

Lesson 1: National action to limit digital distractions in schools can improve students’ achievement and wellbeing (and help teachers teach)

- Nationwide bans can ensure action in all schools. Bans can be implemented in all schools nationally, across all school types.

- Limiting digital distractions can benefit both learning and mental health. These limits can improve student achievement, focus, behaviour, social connection, and mental health.

- Removing distractions from schools can make the biggest difference to students facing the biggest challenges. Lower socio-economic communities can see greater improvements in outcomes.

Lesson 2: There are clear actions schools can take that make the biggest difference in ensuring compliance with national rules

- Clear and consistent rules with firm consequences around phone use are essential. Consistent rules across year levels and firm consequences such as notifying parents and confiscating phones increase compliance.

- Teachers need to understand, support, and enforce the rules. When teachers support, monitor, and enforce rules around device use, student outcomes improve.

- It is key to get students and parents and whānau on board. When students and parents and whānau understand school policy, compliance and outcomes improve.

- Tougher enforcement actions are more effective with secondary students. Notifying parents and confiscating phones can increase compliance, while simply telling students to put their phones away can reduce compliance.

Lesson 3: National action on cell phones helps, but is not enough alone to remove digital distractions and the potential harm of social media

- Banning cell phones alone does not eliminate digital distractions. Half of secondary schools report that wearable devices make it difficult to enforce phone restrictions, and many schools consistently note that access to other devices, such as laptops, also poses a significant challenge.

- Stronger action may be required to properly manage risks from access to devices and social media. While the phone ban has reduced harm linked to social media – such as bullying – and improved students’ mental health, students can still access social media through other means.

Lesson 4: Parents play a key role and need to understand and back schools’ actions to remove digital distractions

- Parents do not always understand and support school rules, and this needs to be addressed. While parents support the intent of limiting digital distractions in the classroom, they have various concerns and do not always support the school rules.

- Parents have an important role to play, and when they are not supportive of school rules, student compliance is compromised. Parent resistance can be a barrier to student compliance.

Recommendations

ERO used the findings and lessons learned to make four recommendations:

Recommendation 1: Keep the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ requirement – it is making a difference.

ERO finds that the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy is making a positive difference to student wellbeing and learning. To maintain this momentum:

- The legal requirement that schools stop students from using or accessing mobile phones while attending school should continue.

- The Ministry of Education should continue to support schools to comply with the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy.

- ERO should continue to monitor implementation and compliance as part of its regular review processes.

- Schools should ensure that teachers clearly understand the school’s rules around phone use, including any exemptions, and are confident in supporting and enforcing them.

Recommendation 2: Increase compliance of secondary students by sharing with schools the approaches that work most.

ERO’s findings indicate that compliance with the policy is less consistent in secondary schools. To improve implementation:

- Secondary schools should continue to use consequences to enforce ‘Phones Away for the Day’ and ensure high compliance across year levels and times of day.

- The Ministry of Education and ERO should provide practical support by sharing effective approaches and strategies that have led to high compliance in other schools.

- Parents should support schools by not contacting their children on cell phones during school hours.

Recommendation 3: Increase parents’ awareness of the benefits of removing cell phones (and other digital distractions) and how they can help.

ERO finds that increasing parent support can further support the success of the policy. To build stronger partnerships:

- The Ministry of Education and ERO should increase visibility of the benefits of removing digital distractions, including impacts on wellbeing and learning.

- Schools should actively engage parents and whānau to help them understand the benefits of removing cell phones, how they can support it at home, and provide alternative ways for parents to communicate with their child during the day.

Recommendation 4: Consider further action to remove other digital distractions and reduce the potential harm of social media at school – learning from the experience of other countries.

ERO’s review suggests that broader digital distractions, including social media, continue to impact student wellbeing and learning. To address this:

- The Government should consider expanding the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy to include other forms of digital distractions such as smartwatches.

- Consider ways to further reduce digital distractions by limiting or removing student access to social media during school hours.

ERO used the findings and lessons learned to make four recommendations:

Recommendation 1: Keep the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ requirement – it is making a difference.

ERO finds that the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy is making a positive difference to student wellbeing and learning. To maintain this momentum:

- The legal requirement that schools stop students from using or accessing mobile phones while attending school should continue.

- The Ministry of Education should continue to support schools to comply with the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy.

- ERO should continue to monitor implementation and compliance as part of its regular review processes.

- Schools should ensure that teachers clearly understand the school’s rules around phone use, including any exemptions, and are confident in supporting and enforcing them.

Recommendation 2: Increase compliance of secondary students by sharing with schools the approaches that work most.

ERO’s findings indicate that compliance with the policy is less consistent in secondary schools. To improve implementation:

- Secondary schools should continue to use consequences to enforce ‘Phones Away for the Day’ and ensure high compliance across year levels and times of day.

- The Ministry of Education and ERO should provide practical support by sharing effective approaches and strategies that have led to high compliance in other schools.

- Parents should support schools by not contacting their children on cell phones during school hours.

Recommendation 3: Increase parents’ awareness of the benefits of removing cell phones (and other digital distractions) and how they can help.

ERO finds that increasing parent support can further support the success of the policy. To build stronger partnerships:

- The Ministry of Education and ERO should increase visibility of the benefits of removing digital distractions, including impacts on wellbeing and learning.

- Schools should actively engage parents and whānau to help them understand the benefits of removing cell phones, how they can support it at home, and provide alternative ways for parents to communicate with their child during the day.

Recommendation 4: Consider further action to remove other digital distractions and reduce the potential harm of social media at school – learning from the experience of other countries.

ERO’s review suggests that broader digital distractions, including social media, continue to impact student wellbeing and learning. To address this:

- The Government should consider expanding the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy to include other forms of digital distractions such as smartwatches.

- Consider ways to further reduce digital distractions by limiting or removing student access to social media during school hours.

What ERO did

For this report, we collected data in Term 2, 2025. We looked at English-medium state schools with Years 7 and above. We collected responses from students, parents and whānau of students, teachers and school leaders6, and school boards. We also spoke with a range of experts and used other evidence and research to support our findings.

The findings of our review are evidenced by a range of data and analysis from:

For this report, we collected data in Term 2, 2025. We looked at English-medium state schools with Years 7 and above. We collected responses from students, parents and whānau of students, teachers and school leaders6, and school boards. We also spoke with a range of experts and used other evidence and research to support our findings.

The findings of our review are evidenced by a range of data and analysis from: