Related insights

Explore related documents that you might be interested in.

Read Online

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank all the new teachers, their principals, school leaders, and mentors who shared their experiences and views with us through interviews and surveys. Thank you for giving your time and sharing your stories so that others may benefit from your successes and challenges.

We acknowledge the considerable support and expertise of the Teaching Council of Aotearoa New Zealand throughout each phase of this project.

We appreciate the support of staff in the government agencies we worked with during the project. We thank the staff from the Social Wellbeing Agency who provided us with data and analysis in a timely and comprehensive manner. We also thank staff at the Ministry of Education, Tertiary Education Commission, and the New Zealand Qualification Authority.

We thank those who provided insights and information to inform our understandings. We also thank those who reviewed drafts and provided feedback.

We acknowledge and thank all the new teachers, their principals, school leaders, and mentors who shared their experiences and views with us through interviews and surveys. Thank you for giving your time and sharing your stories so that others may benefit from your successes and challenges.

We acknowledge the considerable support and expertise of the Teaching Council of Aotearoa New Zealand throughout each phase of this project.

We appreciate the support of staff in the government agencies we worked with during the project. We thank the staff from the Social Wellbeing Agency who provided us with data and analysis in a timely and comprehensive manner. We also thank staff at the Ministry of Education, Tertiary Education Commission, and the New Zealand Qualification Authority.

We thank those who provided insights and information to inform our understandings. We also thank those who reviewed drafts and provided feedback.

Executive summary

Teachers are the most important influence on student outcomes in schools. To achieve the government’s ambition to raise student achievement, it is critical that our teaching workforce is well prepared and supported. ERO looked at how well prepared and supported our new teachers are.

ERO looked at the pathways new teachers take into teaching, and the support available for them in their first two years on the job. We heard from new teachers, as well as the principals and mentor teachers who employ and support them. We wanted find out how well prepared and supported new teachers are.

How prepared are our new teachers?

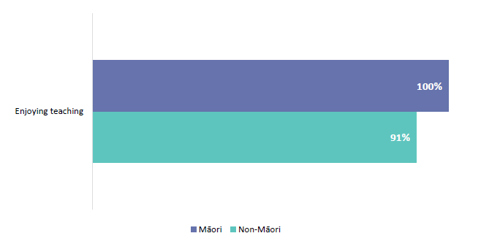

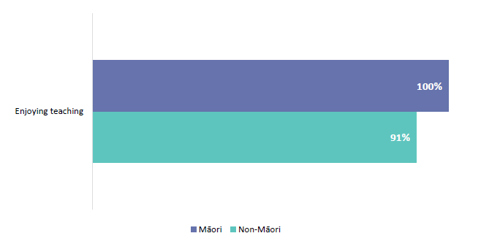

Finding 1: Nearly all new teachers enjoy teaching.

Ninety-three percent of new teachers report they enjoy teaching.

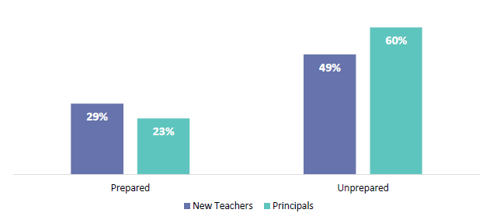

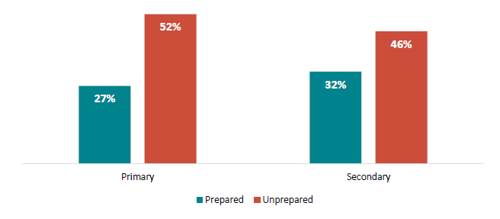

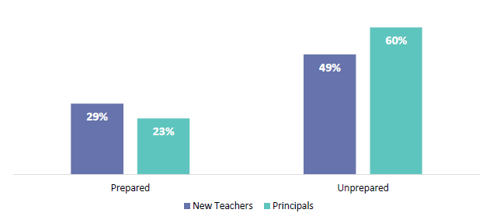

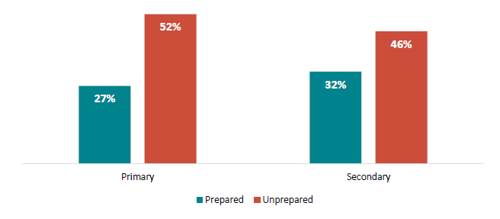

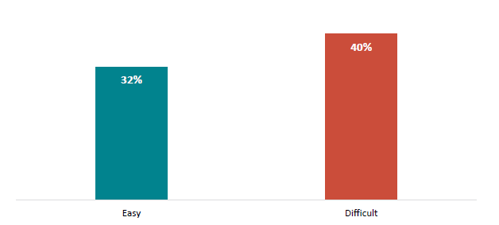

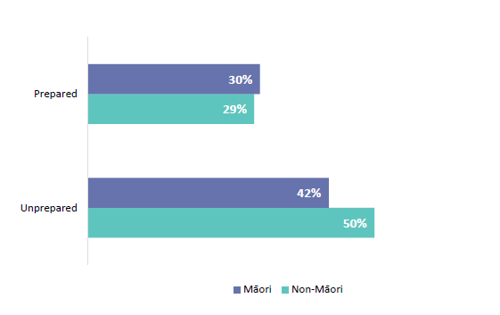

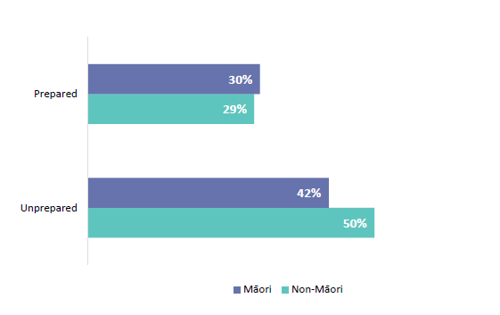

Finding 2: Nearly two thirds (60 percent) of principals report their new teachers are unprepared.

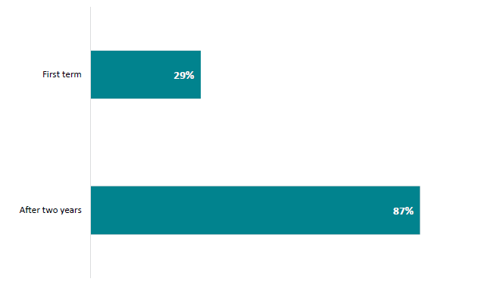

Despite being passionate about teaching, nearly half (49 percent) of new teachers report being unprepared when they started teaching. Less than a third (29 percent) report being prepared.

Many people start in new roles or professions not feeling totally prepared, but it is concerning that only one in five principals report their new teachers are prepared for the role.

New teachers are responsible for their classes and need to be able to manage different aspects of the classroom when they start teaching, so how prepared they are matters for student outcomes.

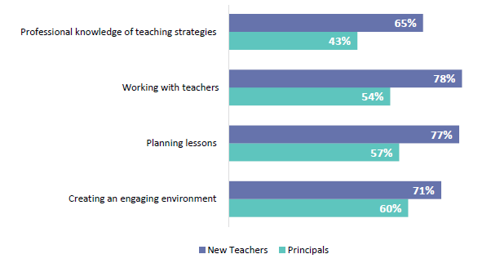

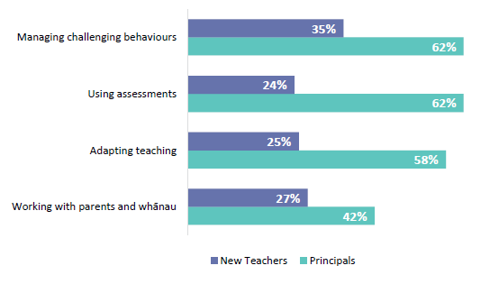

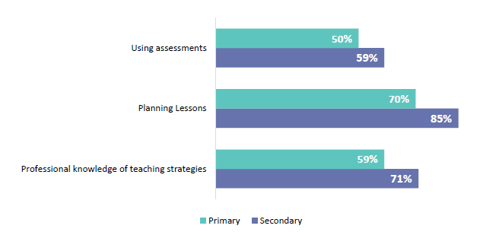

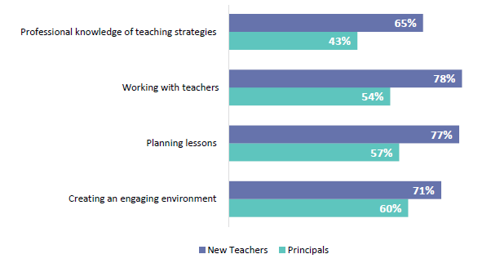

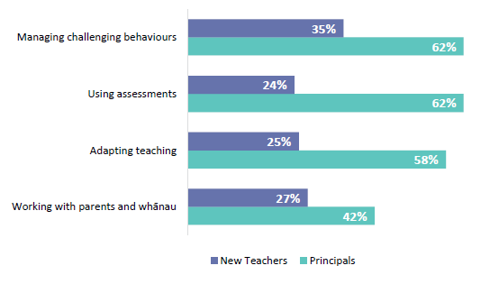

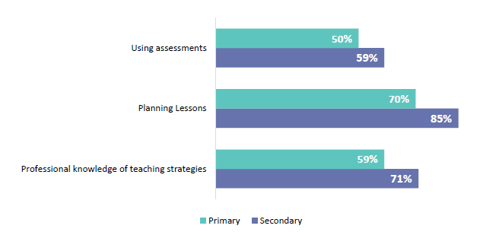

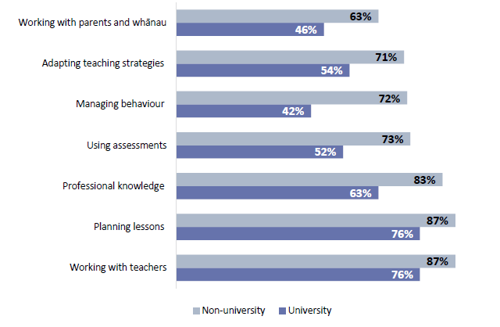

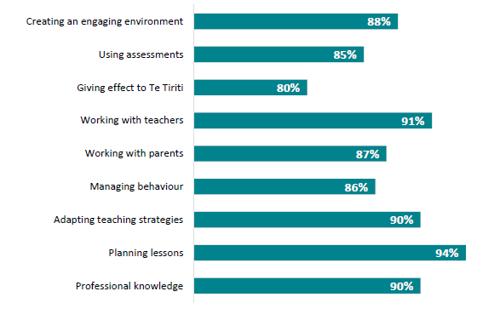

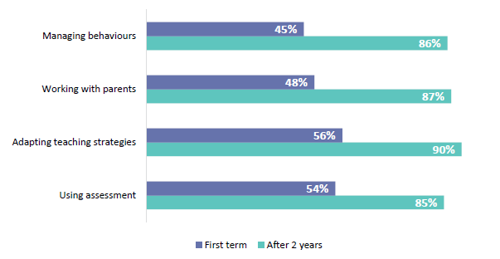

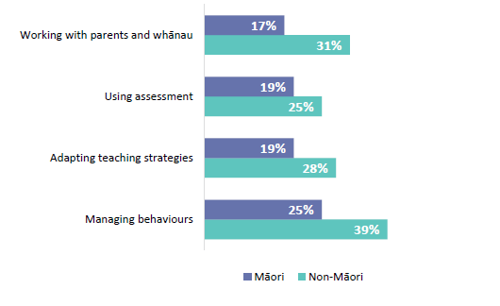

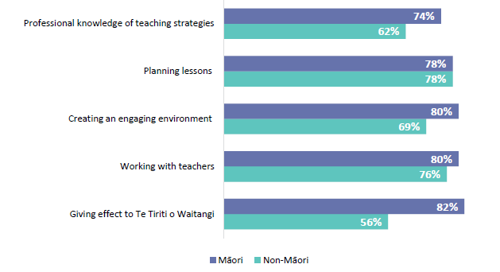

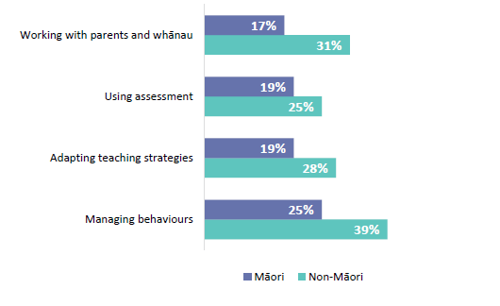

Finding 3: New teachers and principals agree new teachers are well prepared in some areas, but are least prepared in four key areas of professional practice.

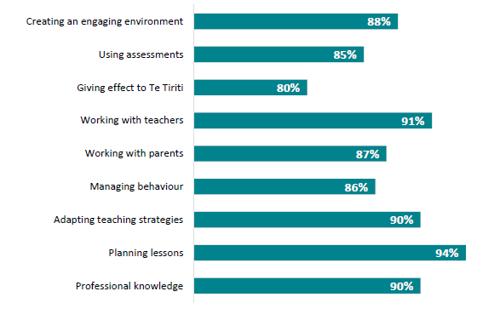

New teachers need to be prepared in a range of teaching practices. While they report being prepared in their professional knowledge of teaching strategies, working with teachers, planning lessons, and creating an engaging environment, they are least prepared for:

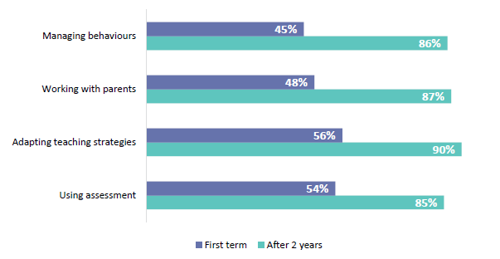

- managing challenging behaviour (35 percent of new teachers report they were not capable in their first term teaching)

- working with parents (27 percent of new teachers report they were not capable in their first term teaching)

- adapting teaching to different students (25 percent of new teachers report they were not capable in their first term teaching)

- using assessments (particularly in primary where 32 percent of new primary teachers report they were not capable in their first term teaching).

This is very concerning, given the level of behaviour issues in our classrooms, and the need to increase the use of assessment.

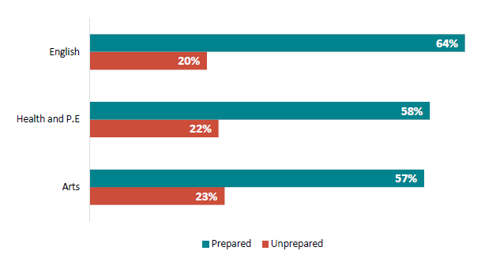

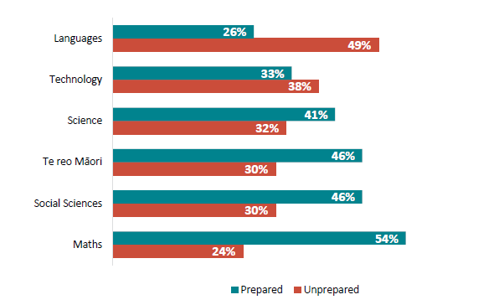

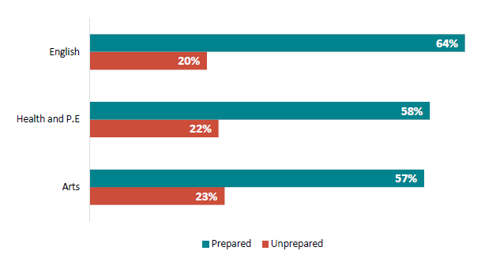

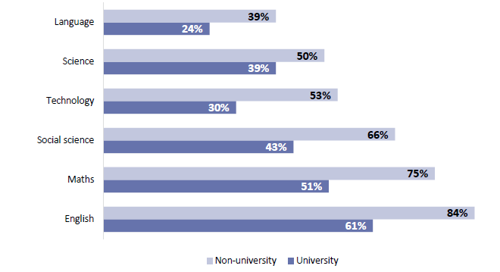

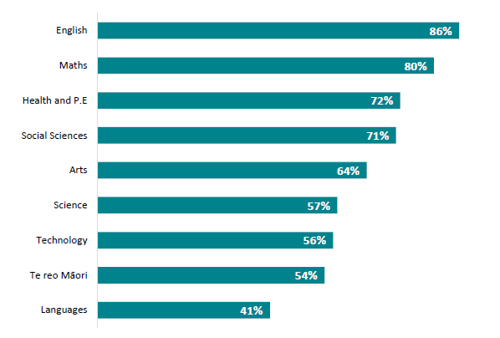

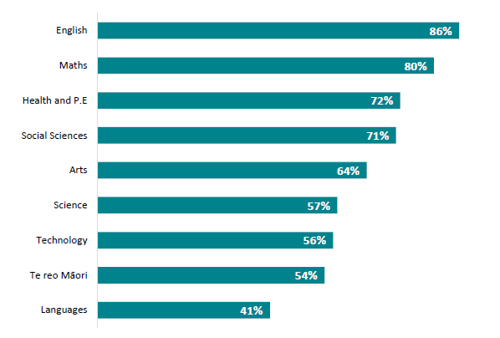

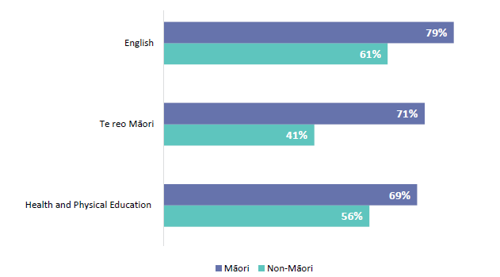

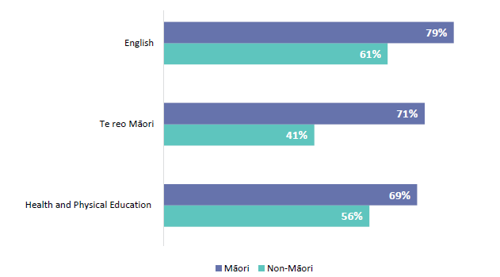

Finding 4: Primary school teachers have to teach many subjects, but new primary school teachers report not being prepared to teach all subjects when they start teaching.

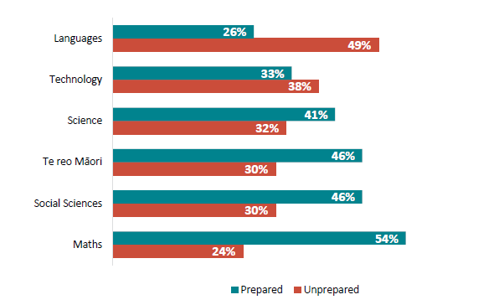

While they report being prepared to teach English, health and physical education, and the arts, they are less prepared to teach in five subject areas. In their first term:

- forty-nine percent of new teachers report being unprepared to teach languages

- thirty-eight percent of new teachers report being unprepared to teach technology

- thirty-two percent report being unprepared to teach science

- thirty percent of new teachers report being unprepared to teach te reo Māori

- twenty-four percent report being unprepared to teach maths.

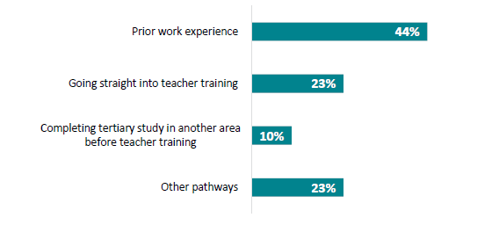

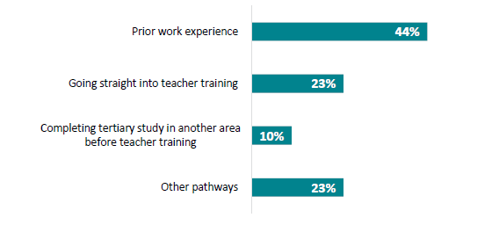

What are new teachers’ pathways into teaching?

Finding 5: Over a quarter of new teachers find their initial teacher education ineffective.

Although half of new teachers (50 percent) reported they found their initial teacher education (ITE) effective, over a quarter (28 percent) described it as ineffective. Those who found it ineffective also report being unprepared for teaching.

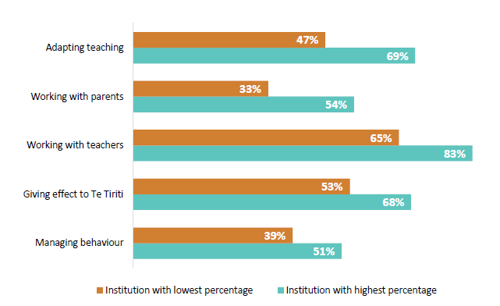

Finding 6: Qualification type does not make a difference to how prepared new teachers are. But there is a significant difference in new teachers’ preparedness based on where they studied.

For graduates from universities, there is a range in how prepared they were. University graduates’ overall preparedness ranges from 20 percent to 34 percent prepared overall.

University graduates’ capability in their first term for different practice areas also varies significantly. For example, 51 percent of graduates from one university report being capable to manage behaviour in their first term, but only 39 percent of graduates from another university reported they were.

Finding 7: Graduates from non-university providers are twice as likely to report being prepared.

Graduates from non-university providers (including wānanga, Polytechnics/Institutes of Technology and Private Training Establishments) report being more prepared than those from universities. Overall, 26 percent of university graduates overall felt prepared, compared to 54 percent of non-university graduates.

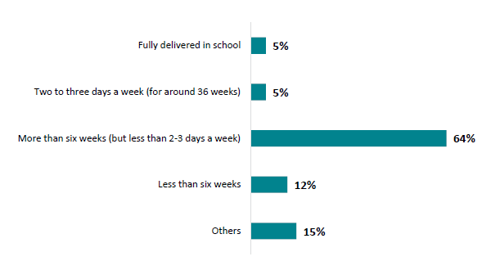

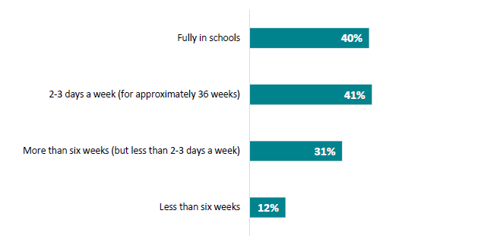

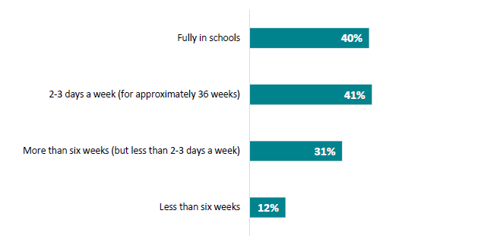

Finding 8: New teachers who receive more time in the classroom during their teacher education report being more prepared.

School placements while studying provide student teachers opportunities to observe real classroom situations, and gradually take charge of teaching with close support and feedback. We found:

- new teachers who spend two or more days per week in schools report being more prepared in their first term teaching

- many new teachers face logistic or financial challenges completing their school placements, as they often have to move away from where they are studying.

What are the characteristics that support new teachers?

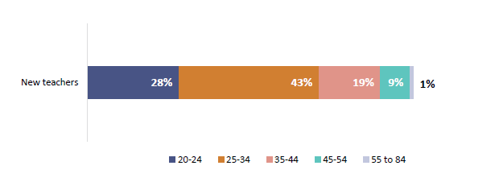

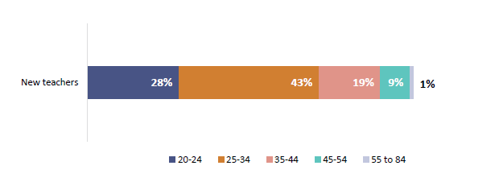

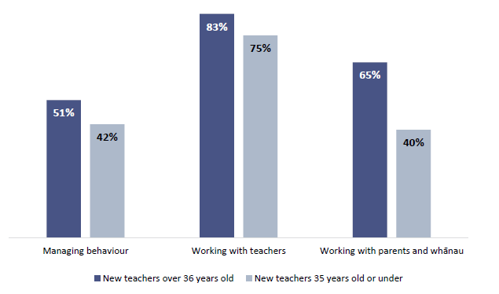

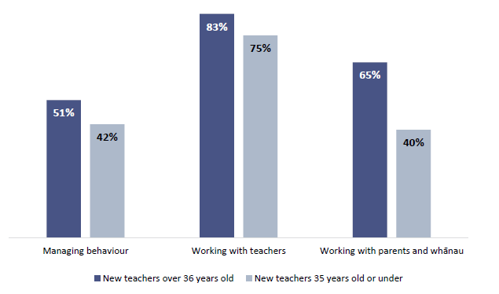

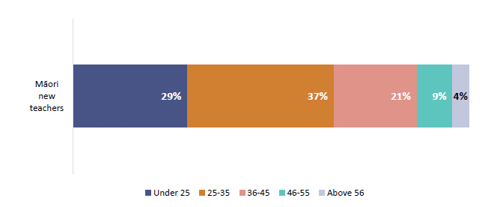

Finding 9: Older new teachers report being more prepared to work with parents and whānau, and manage behaviour.

- Just over half (51 percent) of older new teachers report being prepared to manage behaviour in their first term, compared to 42 percent of younger new teachers.

- Nearly two-thirds (65 percent) of new teachers who are 36 years old or older report being prepared to work with parents and whānau in their first term teaching. Only two-fifths (40 percent) of younger new teachers report being prepared to do this.

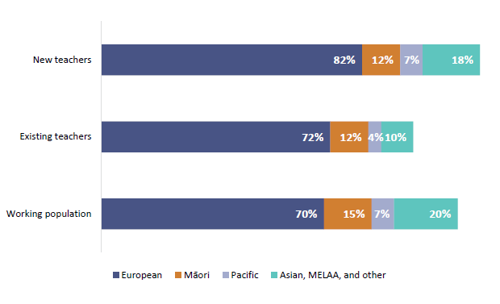

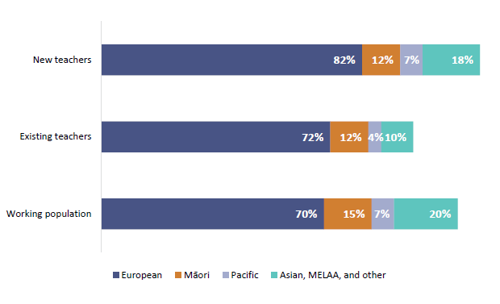

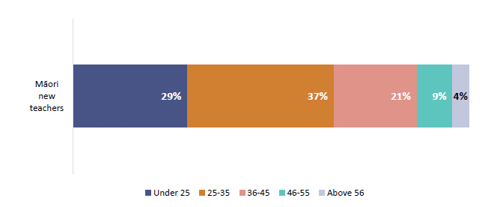

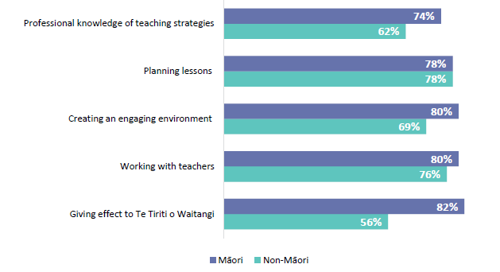

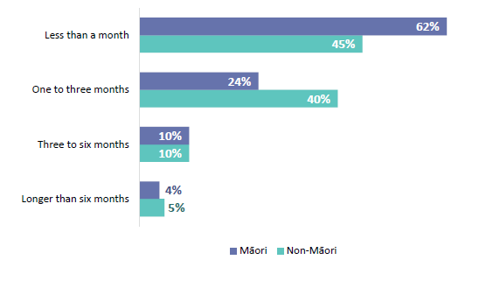

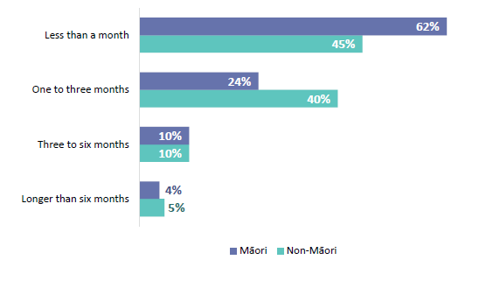

Finding 10: Māori new teachers report being more prepared in several key areas. They are also one and a half times as likely to stay in the profession.

Key differences for Māori new teachers are set out below.

- Fifty-nine percent of Māori new teachers report being capable managing behaviour in their first term, compared to 42 percent of non-Māori new teachers.

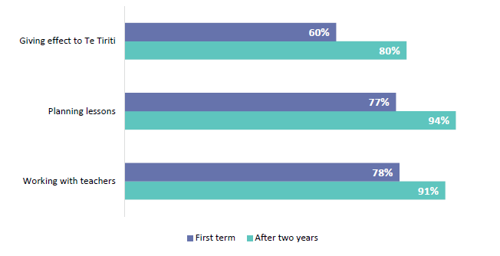

- Eighty-two percent of Māori new teachers report being capable giving effect to te Tiriti o Waitangi, compared to 56 percent of non-Māori new teachers.

- Māori new teachers are more likely to stay in teaching for five years or longer.

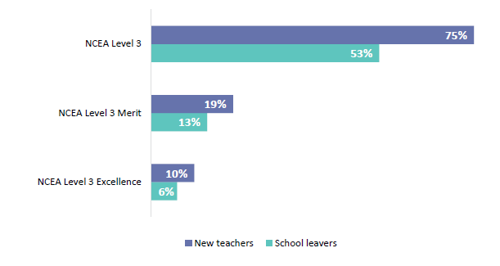

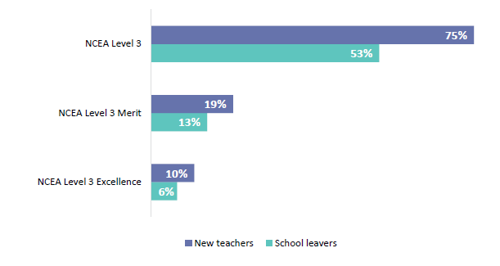

Finding 11: Teachers who achieved an excellence endorsement in NCEA Level 3 are twice as likely to stay in teaching.

New teachers are high achievers, and this matters.

- Ten percent of new teachers achieve NCEA Level 3 with an excellence endorsement. This is almost double the proportion of school leavers overall (6 percent).

- Teachers who achieved Excellence in NCEA Level 3 are twice as likely to stay in teaching for five years or longer.

What supports on-the-job learning?

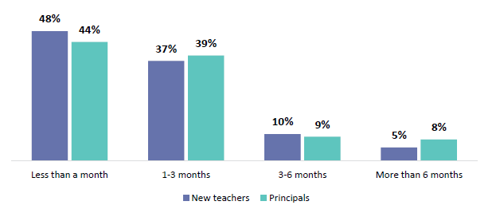

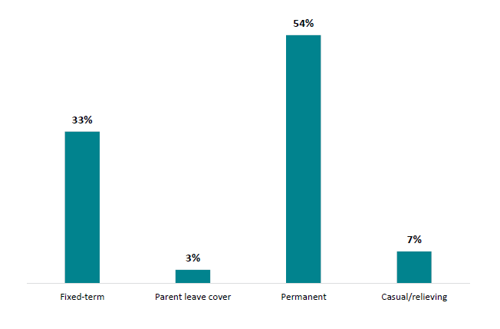

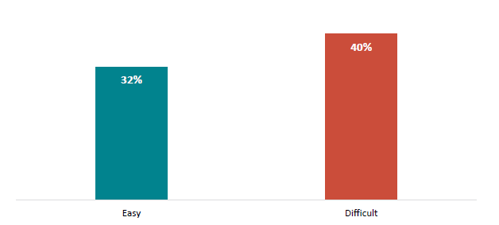

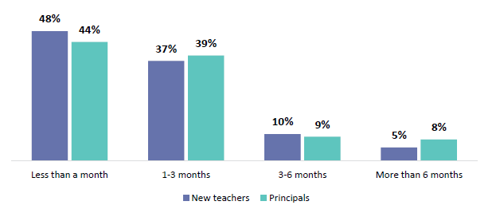

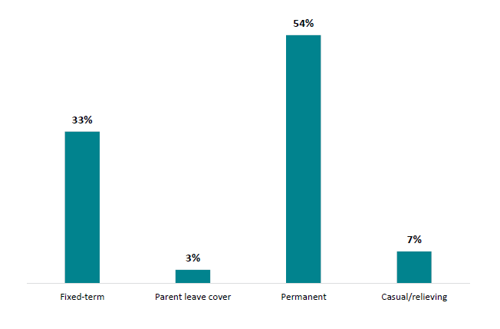

Finding 12: New teachers often lack job security. One in three new teachers are employed on fixed term employment agreements. In primary schools this is half of new teachers.

- Thirty-three percent of new teachers are on fixed term employment agreements.

- Forty-nine percent of primary school new teachers are on fixed term employment agreements.

- New teachers on fixed term employment agreements may have limited experiences of support, and lack stability of employment.

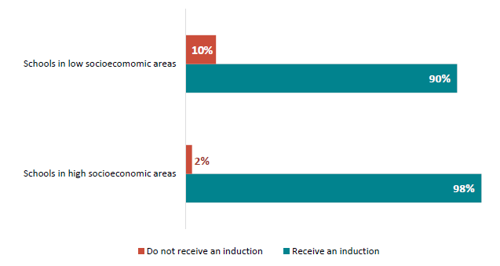

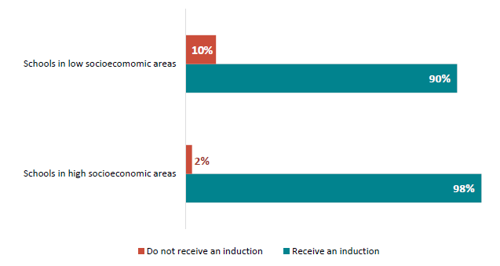

Finding 13: When they start their first job, most new teachers receive an induction. Not all inductions are good, and new teachers in schools in low socioeconomic communities are less likely to receive an induction.

- Ninety-eight percent of new teachers in schools in high socioeconomic areas receive an induction, compared to 90 percent in low socioeconomic areas.

- Fifty-four percent of new teachers find their introduction to school policies as part of their induction effective, but 17 percent of new teachers find their induction ineffective.

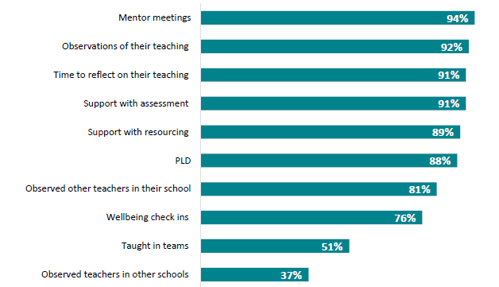

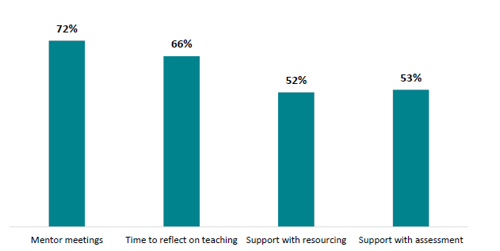

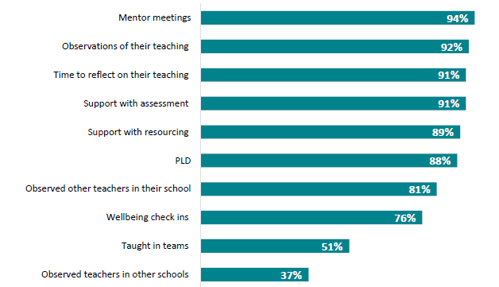

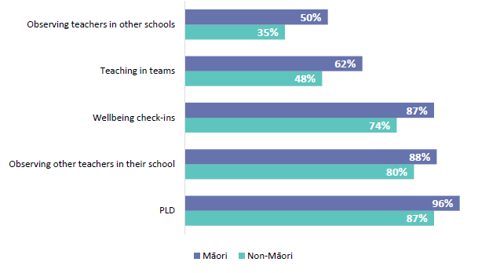

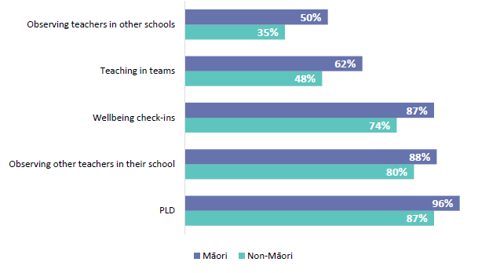

Finding 14: New teachers receive a large range of support.

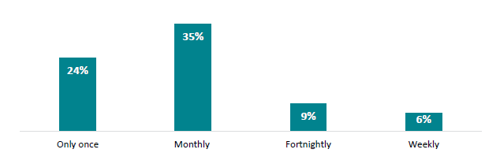

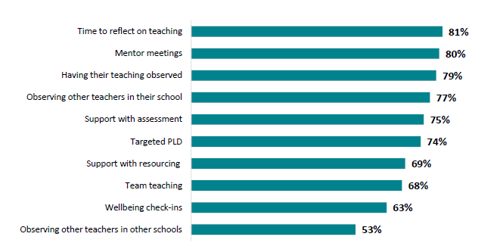

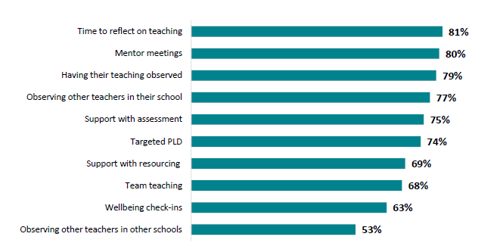

Schools invest in supporting their new teachers. More than 90 percent of new teachers receive mentor meetings, have their teaching observed, and have time to reflect on their teaching.

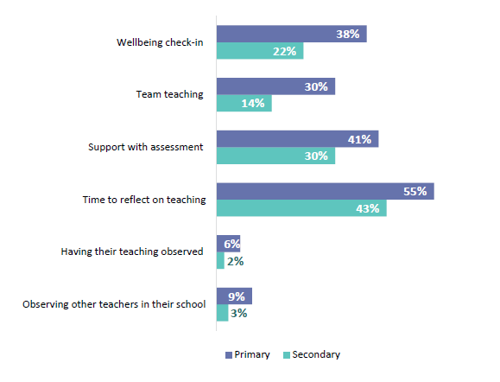

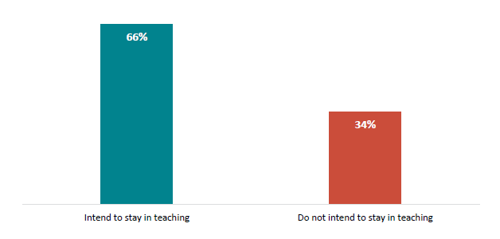

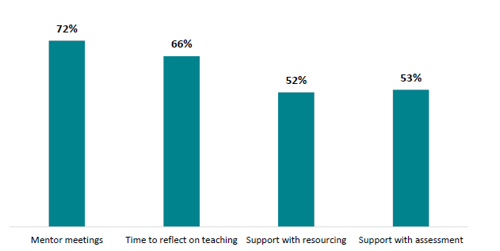

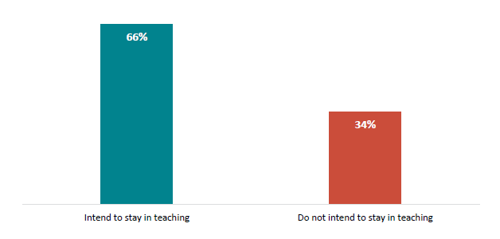

Finding 15: Support for new teachers matters for their wellbeing, and intentions to stay in the role.

New teachers who receive wellbeing check-ins are two times more likely to see themselves in teaching for the next five years.

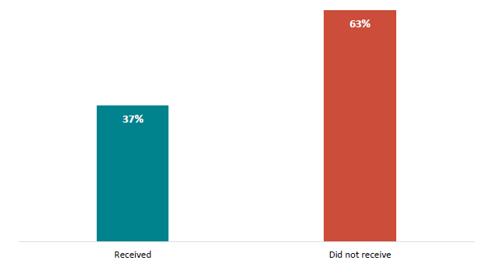

Finding 16: New teachers need to have more time observing other teachers (in their own or other schools).

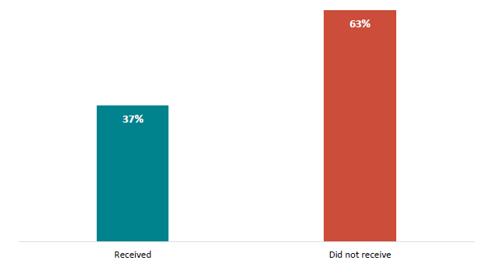

- Only 37 percent of new teachers observe teachers in other schools.

- This is concerning, given we found observing other teachers (alongside having time to reflect on their own teaching) makes the biggest difference in new teachers’ reported capability.

- New teachers who observe others are two times more likely to say they feel capable overall.

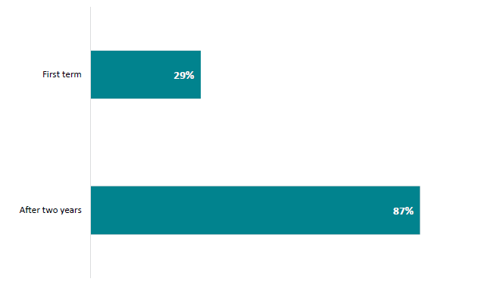

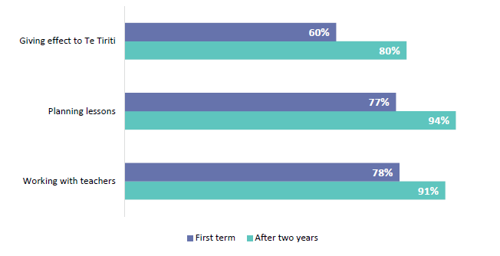

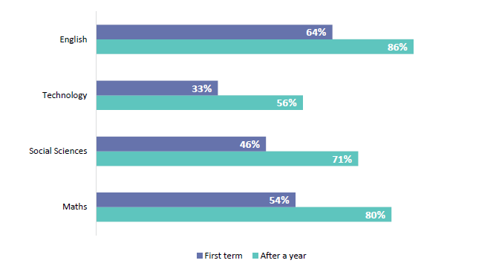

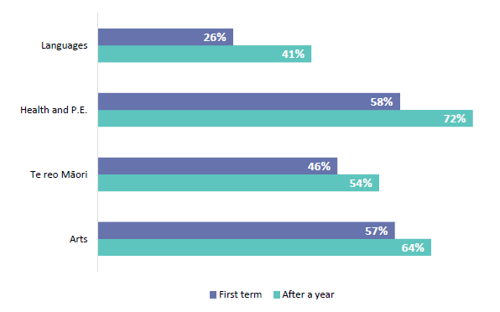

Finding 17: New teachers learn quickly on the job, but after two years, not all new teachers are confident in their practice.

Teachers develop their capability through their first two years’ teaching.

- Managing behaviour and working with parents and whānau are areas where new teachers reported the biggest improvement in confidence from the first term of teaching. However, after two years, one in 10 new teachers report they are still not capable in these areas.

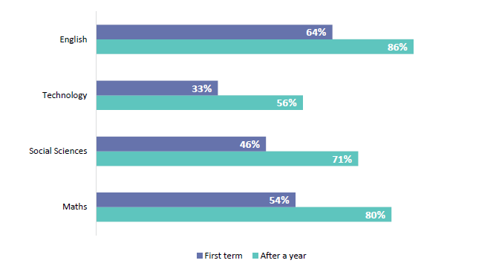

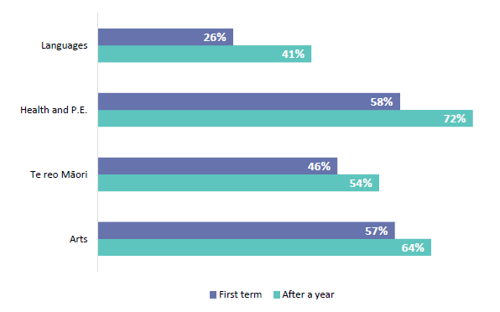

- In primary schools, after one year in the job, teachers’ confidence improves in all subjects, but:

- nine percent are still not confident in teaching maths

- thirteen percent are not confident in teaching science

- fifteen percent are not confident in teaching technology.

What do we need to do?

Based on these 17 key findings, ERO has identified three areas that require action to help ensure new teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand’s English-medium schools are set up to succeed.

- Action Area 1: Attract new teachers who are most likely to have the skills and characteristics to succeed in teaching.

- Action Area 2: Strengthen ITE programmes, focusing on the areas new teachers are least prepared.

- Action Area 3: Provide more structured support for new teachers in their first two years.

Conclusion

New teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand have a big influence on student outcomes. Ensuring they are set up to succeed is critical for them, their students, and the teaching profession. New teachers would benefit from stronger initial teacher education programmes and more structured support in their first two years teaching.

ERO’s recommendations are designed to better prepare and support new teachers as they enter the profession.

Teachers are the most important influence on student outcomes in schools. To achieve the government’s ambition to raise student achievement, it is critical that our teaching workforce is well prepared and supported. ERO looked at how well prepared and supported our new teachers are.

ERO looked at the pathways new teachers take into teaching, and the support available for them in their first two years on the job. We heard from new teachers, as well as the principals and mentor teachers who employ and support them. We wanted find out how well prepared and supported new teachers are.

How prepared are our new teachers?

Finding 1: Nearly all new teachers enjoy teaching.

Ninety-three percent of new teachers report they enjoy teaching.

Finding 2: Nearly two thirds (60 percent) of principals report their new teachers are unprepared.

Despite being passionate about teaching, nearly half (49 percent) of new teachers report being unprepared when they started teaching. Less than a third (29 percent) report being prepared.

Many people start in new roles or professions not feeling totally prepared, but it is concerning that only one in five principals report their new teachers are prepared for the role.

New teachers are responsible for their classes and need to be able to manage different aspects of the classroom when they start teaching, so how prepared they are matters for student outcomes.

Finding 3: New teachers and principals agree new teachers are well prepared in some areas, but are least prepared in four key areas of professional practice.

New teachers need to be prepared in a range of teaching practices. While they report being prepared in their professional knowledge of teaching strategies, working with teachers, planning lessons, and creating an engaging environment, they are least prepared for:

- managing challenging behaviour (35 percent of new teachers report they were not capable in their first term teaching)

- working with parents (27 percent of new teachers report they were not capable in their first term teaching)

- adapting teaching to different students (25 percent of new teachers report they were not capable in their first term teaching)

- using assessments (particularly in primary where 32 percent of new primary teachers report they were not capable in their first term teaching).

This is very concerning, given the level of behaviour issues in our classrooms, and the need to increase the use of assessment.

Finding 4: Primary school teachers have to teach many subjects, but new primary school teachers report not being prepared to teach all subjects when they start teaching.

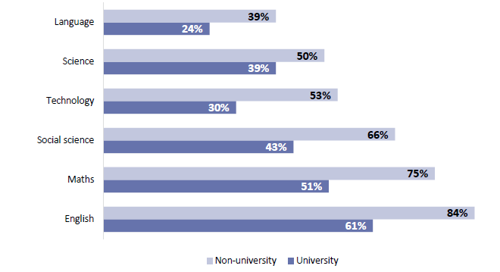

While they report being prepared to teach English, health and physical education, and the arts, they are less prepared to teach in five subject areas. In their first term:

- forty-nine percent of new teachers report being unprepared to teach languages

- thirty-eight percent of new teachers report being unprepared to teach technology

- thirty-two percent report being unprepared to teach science

- thirty percent of new teachers report being unprepared to teach te reo Māori

- twenty-four percent report being unprepared to teach maths.

What are new teachers’ pathways into teaching?

Finding 5: Over a quarter of new teachers find their initial teacher education ineffective.

Although half of new teachers (50 percent) reported they found their initial teacher education (ITE) effective, over a quarter (28 percent) described it as ineffective. Those who found it ineffective also report being unprepared for teaching.

Finding 6: Qualification type does not make a difference to how prepared new teachers are. But there is a significant difference in new teachers’ preparedness based on where they studied.

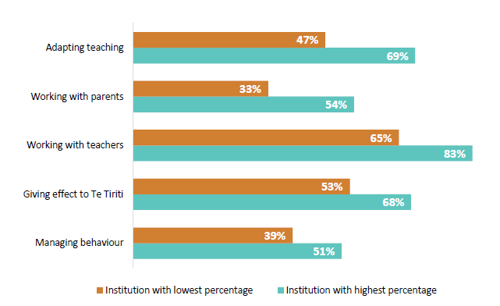

For graduates from universities, there is a range in how prepared they were. University graduates’ overall preparedness ranges from 20 percent to 34 percent prepared overall.

University graduates’ capability in their first term for different practice areas also varies significantly. For example, 51 percent of graduates from one university report being capable to manage behaviour in their first term, but only 39 percent of graduates from another university reported they were.

Finding 7: Graduates from non-university providers are twice as likely to report being prepared.

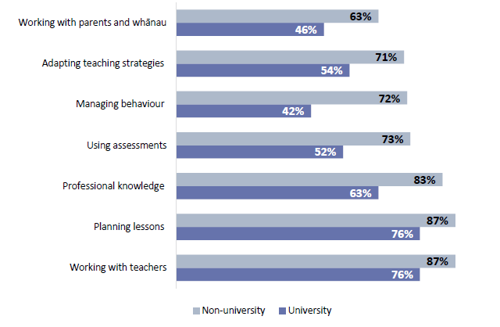

Graduates from non-university providers (including wānanga, Polytechnics/Institutes of Technology and Private Training Establishments) report being more prepared than those from universities. Overall, 26 percent of university graduates overall felt prepared, compared to 54 percent of non-university graduates.

Finding 8: New teachers who receive more time in the classroom during their teacher education report being more prepared.

School placements while studying provide student teachers opportunities to observe real classroom situations, and gradually take charge of teaching with close support and feedback. We found:

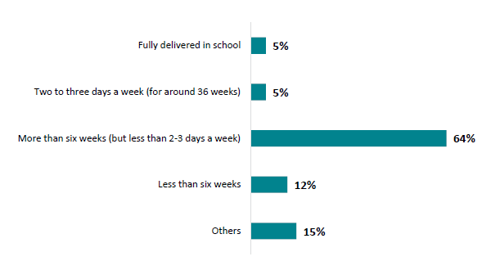

- new teachers who spend two or more days per week in schools report being more prepared in their first term teaching

- many new teachers face logistic or financial challenges completing their school placements, as they often have to move away from where they are studying.

What are the characteristics that support new teachers?

Finding 9: Older new teachers report being more prepared to work with parents and whānau, and manage behaviour.

- Just over half (51 percent) of older new teachers report being prepared to manage behaviour in their first term, compared to 42 percent of younger new teachers.

- Nearly two-thirds (65 percent) of new teachers who are 36 years old or older report being prepared to work with parents and whānau in their first term teaching. Only two-fifths (40 percent) of younger new teachers report being prepared to do this.

Finding 10: Māori new teachers report being more prepared in several key areas. They are also one and a half times as likely to stay in the profession.

Key differences for Māori new teachers are set out below.

- Fifty-nine percent of Māori new teachers report being capable managing behaviour in their first term, compared to 42 percent of non-Māori new teachers.

- Eighty-two percent of Māori new teachers report being capable giving effect to te Tiriti o Waitangi, compared to 56 percent of non-Māori new teachers.

- Māori new teachers are more likely to stay in teaching for five years or longer.

Finding 11: Teachers who achieved an excellence endorsement in NCEA Level 3 are twice as likely to stay in teaching.

New teachers are high achievers, and this matters.

- Ten percent of new teachers achieve NCEA Level 3 with an excellence endorsement. This is almost double the proportion of school leavers overall (6 percent).

- Teachers who achieved Excellence in NCEA Level 3 are twice as likely to stay in teaching for five years or longer.

What supports on-the-job learning?

Finding 12: New teachers often lack job security. One in three new teachers are employed on fixed term employment agreements. In primary schools this is half of new teachers.

- Thirty-three percent of new teachers are on fixed term employment agreements.

- Forty-nine percent of primary school new teachers are on fixed term employment agreements.

- New teachers on fixed term employment agreements may have limited experiences of support, and lack stability of employment.

Finding 13: When they start their first job, most new teachers receive an induction. Not all inductions are good, and new teachers in schools in low socioeconomic communities are less likely to receive an induction.

- Ninety-eight percent of new teachers in schools in high socioeconomic areas receive an induction, compared to 90 percent in low socioeconomic areas.

- Fifty-four percent of new teachers find their introduction to school policies as part of their induction effective, but 17 percent of new teachers find their induction ineffective.

Finding 14: New teachers receive a large range of support.

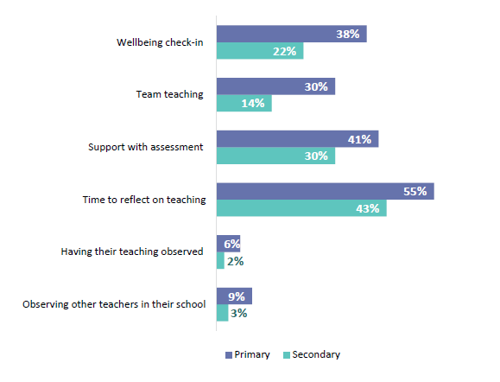

Schools invest in supporting their new teachers. More than 90 percent of new teachers receive mentor meetings, have their teaching observed, and have time to reflect on their teaching.

Finding 15: Support for new teachers matters for their wellbeing, and intentions to stay in the role.

New teachers who receive wellbeing check-ins are two times more likely to see themselves in teaching for the next five years.

Finding 16: New teachers need to have more time observing other teachers (in their own or other schools).

- Only 37 percent of new teachers observe teachers in other schools.

- This is concerning, given we found observing other teachers (alongside having time to reflect on their own teaching) makes the biggest difference in new teachers’ reported capability.

- New teachers who observe others are two times more likely to say they feel capable overall.

Finding 17: New teachers learn quickly on the job, but after two years, not all new teachers are confident in their practice.

Teachers develop their capability through their first two years’ teaching.

- Managing behaviour and working with parents and whānau are areas where new teachers reported the biggest improvement in confidence from the first term of teaching. However, after two years, one in 10 new teachers report they are still not capable in these areas.

- In primary schools, after one year in the job, teachers’ confidence improves in all subjects, but:

- nine percent are still not confident in teaching maths

- thirteen percent are not confident in teaching science

- fifteen percent are not confident in teaching technology.

What do we need to do?

Based on these 17 key findings, ERO has identified three areas that require action to help ensure new teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand’s English-medium schools are set up to succeed.

- Action Area 1: Attract new teachers who are most likely to have the skills and characteristics to succeed in teaching.

- Action Area 2: Strengthen ITE programmes, focusing on the areas new teachers are least prepared.

- Action Area 3: Provide more structured support for new teachers in their first two years.

Conclusion

New teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand have a big influence on student outcomes. Ensuring they are set up to succeed is critical for them, their students, and the teaching profession. New teachers would benefit from stronger initial teacher education programmes and more structured support in their first two years teaching.

ERO’s recommendations are designed to better prepare and support new teachers as they enter the profession.

About this report

Teachers have one of the biggest influences on students’ outcomes. Ensuring that teachers are well set up to begin their career is important for them, their students, and for the teaching profession. New teachers require a good grounding in what works for teaching and learning, an opportunity to apply this in practical contexts, and support to develop and grow.

This report looks at the pathways aspiring teachers take to begin their journey in schools, how this helps them be prepared, and how they are supported to grow and improve in their first two years of teaching. By looking at their experiences and drawing on evidence from research, we can learn how we can better prepare and support new teachers.

This evaluation was commissioned by the Chief Review Officer, in partnership with the Teaching Council of Aotearoa New Zealand (the Teaching Council).

The Teaching Council is the professional body for teachers in early childhood education, primary, and secondary schooling. They promote the quality of teaching practice by registering teachers, setting and maintaining professional standards, and ensuring teachers are competent and fit to practice. ERO worked in partnership with the Teaching Council, who provided advice and guidance throughout this project.

The Education Review Office (ERO) is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early learning services, schools, and kura. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports schools to provide quality education for Aotearoa New Zealand’s learners. ERO last reviewed new teachers’ preparation and confidence to teach in 2017.

|

New teachers are sometimes described as ‘Beginning teachers’ or ‘PCTs’ (Provisionally Certificated Teachers). In this report, we use ‘new teachers’ to describe teachers who did their initial teacher education in Aotearoa New Zealand, and are in their first two years of teaching. Many of the new teachers in this report studied during the Covid-19 pandemic, and were graduates from initial teacher education programmes approved under the previous Initial Teacher Education Programme Approval Requirements (updated in 2019). |

This report describes what we found about pathways and supports for new teachers as they move into the role and in their first two years. We highlight the experiences of teachers, as well as the experiences of mentor teachers and principals who employ new teachers at their schools. We describe what pathways and supports look like, the impact these have on new teachers’ preparedness when they first start teaching, and their capability while in the role. We also suggest areas for improvement regarding pathways and support.

What we looked at

This evaluation looked at pathways and supports for new teachers in their first two years in the profession. We wanted to answer the question:

- How do we ensure that new teachers are set up to succeed?

To deliver on this, we designed an evaluation to answer four key questions about new teachers.

- How prepared do new teachers report being when they start to teach?

- How do pathways into teaching impact how teachers report their preparedness?

- How does their reported capability improve on the job?

- What support on the job has the most impact on improving teachers’ reported capabilities?

We looked at aspects of professional practice and teachers’ subject expertise.

Where we looked

This report focuses on teachers who hold a Provisional Practising Certificate and are in their first two years of teaching at a school. In this period, they receive an induction and mentoring programme within their school. We looked at new teachers across Aotearoa New Zealand English-medium state and state‑integrated primary, intermediate, and secondary schools.

How we found out about pathways and supports for new teachers

We have taken a mixed-methods approach to deliver breadth and depth in this evaluation. We built our understanding of pathways and supports for new teachers through:

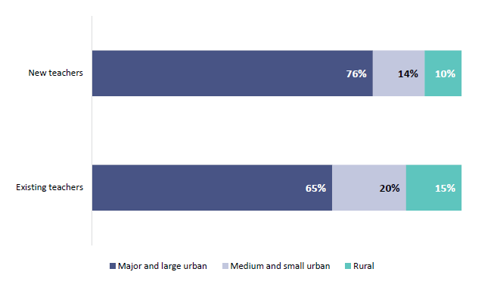

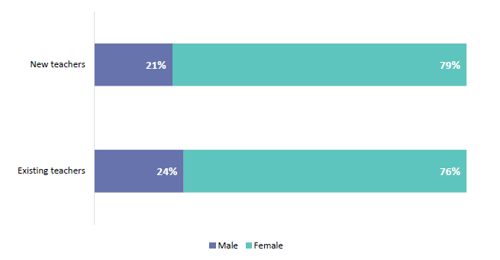

- a survey of 751 new teachers – nearly 10 percent of all Provisionally Certificated Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand, and representative of their ethnicity, gender, and schools

- a survey of 278 principals at schools that employ new teachers – 12 percent of schools, and representative of schools

- interviews with 23 new teachers from different school settings, school leaders from four schools, and four mentor teachers

- data from the Ministry of Education, the Teaching Council, and StatsNZ’s Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI)

- a literature review of the local and international evidence around pathways and support that prepare new teachers

- interviews with experts at the Teaching Council and the Ministry of Education.

When we discuss how prepared, capable and confident new teachers are, we draw on the reports of new teachers themselves, as well as school principals. Throughout this report, we focus on new teachers in English-medium state and state-integrated schools.

Report structure

This report is divided into seven parts.

- Part 1 sets out the process to become a new teacher. We explain the pathways into teaching, and the systems and processes that support new teachers. We look at what has changed, and how Aotearoa New Zealand compares to other countries.

- Part 2 describes who our new teachers are, and the pathways they take into teaching. We look at what we mean by ‘new teachers’, and what this group looks like compared to the overall teacher workforce. We cover the qualifications they complete, where they study, their experiences of Professional Experience Placement (placement), and the broader life experiences they bring to the role.

- Part 3 focuses on how well-prepared new teachers report being overall, as well as for individual components of practice. We also explore what makes a difference in how prepared new teachers are.

- Part 4 sets out how well new teachers are supported in their first two years. We share their experiences through finding a job, induction, and the ongoing supports they receive. We explore which supports make the biggest difference to teachers’ capability and confidence, and their thoughts about staying in the profession.

- Part 5 describes how well teachers learn on the job, from when they start as teachers, through their first two years of employment.

- Part 6 focuses on how things are for Māori new teachers. We describe their pathways, reported preparedness, and support they receive.

- Part 7 sets out our key findings and recommendations for action.

Teachers have one of the biggest influences on students’ outcomes. Ensuring that teachers are well set up to begin their career is important for them, their students, and for the teaching profession. New teachers require a good grounding in what works for teaching and learning, an opportunity to apply this in practical contexts, and support to develop and grow.

This report looks at the pathways aspiring teachers take to begin their journey in schools, how this helps them be prepared, and how they are supported to grow and improve in their first two years of teaching. By looking at their experiences and drawing on evidence from research, we can learn how we can better prepare and support new teachers.

This evaluation was commissioned by the Chief Review Officer, in partnership with the Teaching Council of Aotearoa New Zealand (the Teaching Council).

The Teaching Council is the professional body for teachers in early childhood education, primary, and secondary schooling. They promote the quality of teaching practice by registering teachers, setting and maintaining professional standards, and ensuring teachers are competent and fit to practice. ERO worked in partnership with the Teaching Council, who provided advice and guidance throughout this project.

The Education Review Office (ERO) is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early learning services, schools, and kura. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports schools to provide quality education for Aotearoa New Zealand’s learners. ERO last reviewed new teachers’ preparation and confidence to teach in 2017.

|

New teachers are sometimes described as ‘Beginning teachers’ or ‘PCTs’ (Provisionally Certificated Teachers). In this report, we use ‘new teachers’ to describe teachers who did their initial teacher education in Aotearoa New Zealand, and are in their first two years of teaching. Many of the new teachers in this report studied during the Covid-19 pandemic, and were graduates from initial teacher education programmes approved under the previous Initial Teacher Education Programme Approval Requirements (updated in 2019). |

This report describes what we found about pathways and supports for new teachers as they move into the role and in their first two years. We highlight the experiences of teachers, as well as the experiences of mentor teachers and principals who employ new teachers at their schools. We describe what pathways and supports look like, the impact these have on new teachers’ preparedness when they first start teaching, and their capability while in the role. We also suggest areas for improvement regarding pathways and support.

What we looked at

This evaluation looked at pathways and supports for new teachers in their first two years in the profession. We wanted to answer the question:

- How do we ensure that new teachers are set up to succeed?

To deliver on this, we designed an evaluation to answer four key questions about new teachers.

- How prepared do new teachers report being when they start to teach?

- How do pathways into teaching impact how teachers report their preparedness?

- How does their reported capability improve on the job?

- What support on the job has the most impact on improving teachers’ reported capabilities?

We looked at aspects of professional practice and teachers’ subject expertise.

Where we looked

This report focuses on teachers who hold a Provisional Practising Certificate and are in their first two years of teaching at a school. In this period, they receive an induction and mentoring programme within their school. We looked at new teachers across Aotearoa New Zealand English-medium state and state‑integrated primary, intermediate, and secondary schools.

How we found out about pathways and supports for new teachers

We have taken a mixed-methods approach to deliver breadth and depth in this evaluation. We built our understanding of pathways and supports for new teachers through:

- a survey of 751 new teachers – nearly 10 percent of all Provisionally Certificated Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand, and representative of their ethnicity, gender, and schools

- a survey of 278 principals at schools that employ new teachers – 12 percent of schools, and representative of schools

- interviews with 23 new teachers from different school settings, school leaders from four schools, and four mentor teachers

- data from the Ministry of Education, the Teaching Council, and StatsNZ’s Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI)

- a literature review of the local and international evidence around pathways and support that prepare new teachers

- interviews with experts at the Teaching Council and the Ministry of Education.

When we discuss how prepared, capable and confident new teachers are, we draw on the reports of new teachers themselves, as well as school principals. Throughout this report, we focus on new teachers in English-medium state and state-integrated schools.

Report structure

This report is divided into seven parts.

- Part 1 sets out the process to become a new teacher. We explain the pathways into teaching, and the systems and processes that support new teachers. We look at what has changed, and how Aotearoa New Zealand compares to other countries.

- Part 2 describes who our new teachers are, and the pathways they take into teaching. We look at what we mean by ‘new teachers’, and what this group looks like compared to the overall teacher workforce. We cover the qualifications they complete, where they study, their experiences of Professional Experience Placement (placement), and the broader life experiences they bring to the role.

- Part 3 focuses on how well-prepared new teachers report being overall, as well as for individual components of practice. We also explore what makes a difference in how prepared new teachers are.

- Part 4 sets out how well new teachers are supported in their first two years. We share their experiences through finding a job, induction, and the ongoing supports they receive. We explore which supports make the biggest difference to teachers’ capability and confidence, and their thoughts about staying in the profession.

- Part 5 describes how well teachers learn on the job, from when they start as teachers, through their first two years of employment.

- Part 6 focuses on how things are for Māori new teachers. We describe their pathways, reported preparedness, and support they receive.

- Part 7 sets out our key findings and recommendations for action.

Part 1: What is the process to become a new teacher?

Aotearoa New Zealand needs good teachers to enable all students to achieve. Teaching is a profession that needs a high level of skill to do well. As our population grows and the teaching workforce ages, demand for new teachers is high. It is therefore important that every school has well-qualified, diverse, and competent teachers to ensure students have the best possible learning outcomes.

To become a teacher in Aotearoa New Zealand, prospective teachers undertake Initial Teacher Education (ITE) and gain a teaching qualification through an approved provider. A wide range of programmes, providers, and qualifications are available.

After registering to become a new teacher, they are issued a Provisional Practising Certificate. During this provisional period they receive a range of support and are expected to progress towards demonstrating the Standards for the Teaching Profession.

The Standards for the Teaching Profession| Ngā Paerewa are made up of six standards that describe what high quality teaching practice looks like. The Standards is issued by the Teaching Council and apply to all teachers. Teachers need to demonstrate they meet the Standards to be certificated by the Teaching Council to teach.

This section sets out:

- why ERO focused on new teachers

- how you become a new teacher in Aotearoa New Zealand

- the systems and supports for new teachers

- how Aotearoa New Zealand compares to other countries’ teacher education pathways

- what we mean by being ‘prepared to teach’.

1) Why has ERO focused on new teachers?

The teaching role is complex.

The teaching role in schools is complex, and there are many demands on teachers. Teachers need to be able to draw on their professional knowledge of teaching strategies to plan and deliver lessons in a way that engages students. They need to use what they know about learners, including from assessment, understanding of their parents and culture, and knowing about any disabilities or impairments, to adapt the way they apply these strategies. Alongside this, teachers have to manage classroom behaviour, work with parents and whānau, and other school staff.

We have a significant need to strengthen the quality of teaching in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Student achievement in Aotearoa New Zealand is a concern. Recent PISA results show an overall downward trend in student achievement in maths, reading and science since 2006.(1) Aotearoa New Zealand’s national performance monitoring study (the National Monitoring Study of Student Achievement, NMSSA) also shows declining achievement in English,(2) but no significant changes in maths(3) or science.(4)

Although NMSSA shows achievement staying steady for maths and science, and most Year 4 students are achieving at or above the curriculum level, significantly fewer Year 8 students achieve at the expected level (42 percent in maths, and only 20 percent in science).

Around one in 10 children in Aotearoa New Zealand are disabled. Unfortunately, ERO found in 2022 that over half of school teachers lack confidence in teaching disabled learners.(5) A recent ERO report also shows disruptive behaviour in classrooms is increasing, and this has a negative impact on students’ learning.(6) Ensuring we have teachers that demonstrate effective practice is essential if we are to make the improvements needed.

We have an ageing teaching workforce, and demand for teachers will increase in the next five years.

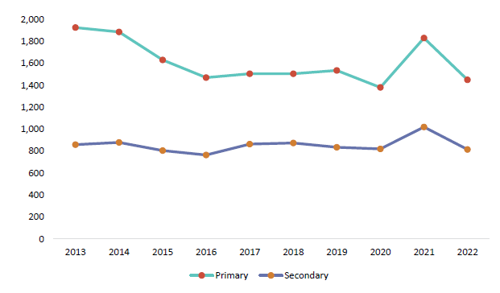

Our teaching workforce is ageing. There were 72,950 teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand primary and secondary schools in 2022. Nearly 30 percent of these teachers are 55-years-old or older.

The Ministry of Education (the Ministry) predicts that, although demand for primary teachers will decrease into 2025, demand for secondary teachers will grow. If the retention rate and intake of teachers continues to be low, there will be a shortage of up to 620 secondary school teachers. The Ministry also anticipates an ongoing need to grow supply in some subjects and in certain parts of the country(7).

(The teacher demand and supply data has limitations in that specific areas of needs cannot be definitively identified, for example, demand and supply in different regions.)

The Government has a strong focus on improving student outcomes.

The Government’s ‘Teaching the basics brilliantly’ plan for education places a stronger focus on ensuring best practice, building off evidence, and calls for stronger rigour in classroom teaching. To do this, the Government draws on research from the last two decades, into the science of teaching and learning.(8)

The Government education plan signals a shift to a more strongly knowledge rich curriculum with learning less likely being left to chance, and places an increasing emphasis on ‘subject specific pedagogies’ rather than general pedagogical approaches.

To deliver on this, initial teacher education needs to prepare new teachers to be at the forefront of the changes.

Teachers are the most important in-school contributor to student outcomes.

Effective and high-quality teaching has a large impact on student outcomes.(9)(10) Research has found that students starting out at a similar level of achievement could be as many as 53 percentiles apart after three years, depending on the capabilities of their teacher.(11)

There is increasing international evidence about what effective preparation for teaching involves. New teachers learn from observing high quality teaching, receiving frequent and useful feedback, and interacting with a collaborative teaching community. For some, the quality of their placement experience makes the difference between passing and failing a course,(12) and their future success as teachers.

Initial teacher education alone cannot make the transformation to teaching and learning we need, to see the improvements we want. It is important that all parts of the education system work effectively to deliver a high-quality teaching workforce, and high-quality teaching and learning in our classrooms. Ensuring new teachers are confident and well-equipped to teach is an important contributing component to this.

2) How do you become a new teacher in Aotearoa New Zealand?

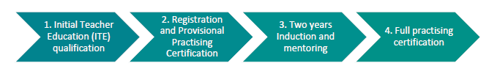

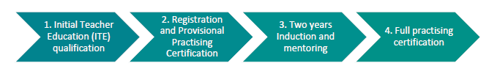

There are four steps to becoming a teacher in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Teachers must complete an ITE qualification before they can register as a teacher. They then complete a two-year programme of induction and mentoring, before being eligible for full certification as a teacher.

a) What are the components of ITE?

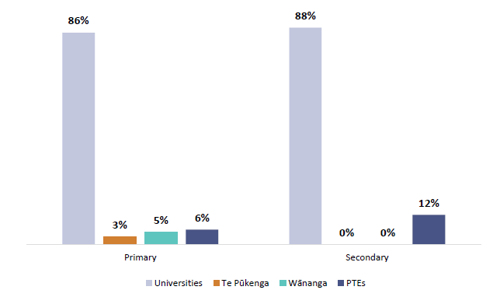

There are 87 different ITE programmes, available from 25 approved providers.(13) These providers include universities, institutes of technology, polytechnics, wānanga, and private training establishments. The full list of providers is included in Appendix 2.

Providers need to meet requirements to be approved. These have recently been strengthened and development is continuing.

Standards for the Teaching ProfessionThe Standards for the Teaching Profession were developed by the Education Council (now the Teaching Council of Aotearoa New Zealand) in 2017 and apply to all practising teachers. They are made up of six standards that describe “the essential professional knowledge in practice and professional relationships and values required for effective teaching” to be used in any setting. The six standards are set out below. 1. Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership: demonstrate commitment to tangata whenuatanga and Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership in Aotearoa New Zealand. 2. Professional learning: use inquiry, collaborative problem-solving, and professional learning to improve professional capability to impact on the learning and achievement of all learners. 3. Professional relationships: establish and maintain professional relationships and behaviours focused on the learning and wellbeing of each learner. 4. Learning-focused culture: develop a culture that is focused on learning, and is characterised by respect, inclusion, empathy, collaboration, and safety. 5. Design for learning: design learning based on curriculum and pedagogical knowledge, assessment information and an understanding of each learner’s strengths, interests, needs, identities, languages, and cultures. 6. Teaching: teach and respond to learners in a knowledgeable and adaptive way to progress their learning at an appropriate depth and pace. The Code of Professional Responsibility sets out the standards of conduct and integrity expected of everyone in the teaching profession. |

Following our report in 2017, the Teaching Council updated the requirements for ITE provision to become the Initial Teacher Education Programme Approval, Monitoring and Review Requirements (the requirements) in 2019. The requirements increased the number of days for practicum placement and changes to compulsory assessment to ensure “all newly qualified teachers [are] equipped for their first teaching role and have the skills to continue to learn and adapt their practice to meet future challenges.”(14)

The ITE requirements include:

- candidates meeting specific entry requirements for admission into ITE, including competency in literacy and numeracy

- development of student teachers’ capability in te reo Māori

- a requirement of 80 days (16 weeks) in school teaching practice for one-year and two-year programmes, and 120 days (24 weeks) for three-year or longer programmes

- graduating students must be successful in their assessment against the assessment framework. This is linked to authentic practice situations and includes 10 to 15 Key Teaching Tasks (KTTs), aligned to the Standards for the Teaching Profession, and a final Culminating Integrative Assessment(15)

- processes for monitoring and review, national moderation, audits, and special reviews

- authentic partnership between ITE providers and schools to deliver a programme for their student teachers. This is intended to address the gap between theory and practice.(16)

ITE providers must design their programme content to meet these requirements. Providers had until 1 January 2022 to apply for approval under these updated requirements. A programme approval panel established by the Teaching Council reviews the programme before it can be approved.

ITE graduates are expected to be able to meet the Teaching Standards, with support. The Key Teaching Tasks (KTTs) are tasks that graduating teachers are expected to be capable of carrying out on day one of a teaching job. Currently, these are developed by the ITE providers, and may vary between providers. The Teaching Council is looking to develop a set of core or compulsory KTTs. This could include specific expectations in relation to literacy and numeracy teaching, relevant for the sub-sector they will be teaching in.

ITE providers partner with schools to support new teachers’ education and development. Most commonly, the partnership is around supporting students’ practical experience in schools (or early childhood services). Some providers continue to work with their graduates as they begin their first job in schools by providing tailored professional development or networking opportunities.

Placement

Placements are blocks of time assigned to student teachers to gain teaching experience in a school to build their confidence and competence for when they begin their teaching.

Associate teachers are appointed in schools to support the learning and assessment of student teachers and there is provision in teachers’ collective employment agreement to recognise this additional work. There is no required process or accreditation to become an associate teacher, it is at the discretion of the school leader.

For each placement, they work with their associate teacher (the regular teacher for the class) to practise their skills and apply their knowledge to make links between theory and practice in real teaching contexts.

While the minimum placement duration is set out by the Teaching Council, placement can look different, depending on ITE providers and different programmes.

The impact of Covid-19

In 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic, the Teaching Council made temporary changes to ITE requirements, including:

- up to a 25 percent reduction of required in-school placements

- graduates from ITE affected by a reduction in placements were eligible for an ‘enhanced induction and mentoring programme’, funded by the Ministry of Education and delivered through the University of Auckland

- removal of the requirement for ‘blocks’ of four to six weeks of consecutive placements

- ITE providers could apply to replace placements with ‘alternative practical experiences’ that count towards the placement requirements.

We do not know when the teachers involved in this research completed their ITE.

We estimate approximately four in five new teachers are likely to have had their ITE impacted by Covid-19. Most of these new teachers were completing Bachelor’s qualifications. This means that their placements were shortened or moved online. This is important for how prepared new teachers reported they were as they came into teaching.

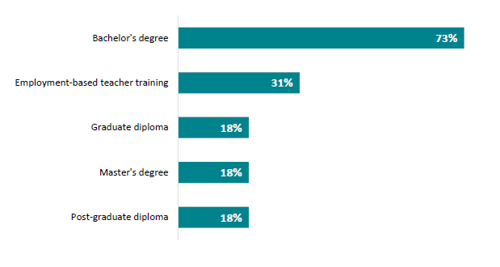

a) What and where can new teachers study?

bhe 25 ITE providers include seven universities and 18 non-university providers, offering 87 programmes approved by the Teaching Council.(17)

Table 1: ITE qualification options

|

Degree Type |

Length of full-time study |

Aotearoa New Zealand Qualifications Framework Level |

|

Bachelor of Education / Bachelor of Teaching |

3 years |

Level 7 |

|

Graduate Diploma of Teaching |

1 year |

Level 7 |

|

Post-graduate Diploma of Teaching |

1 year or 2-year employment-based programme (e.g. Ako Mātātupu - Teach First NZ) |

Level 8 |

|

Master of Teaching and Learning |

2 years |

Level 9 |

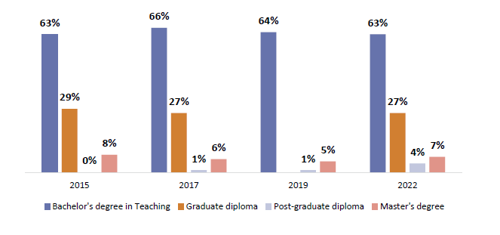

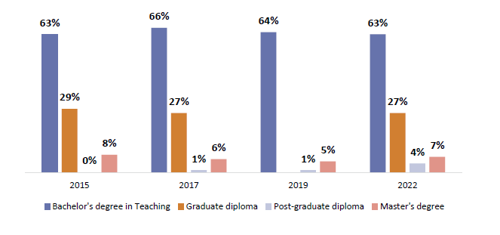

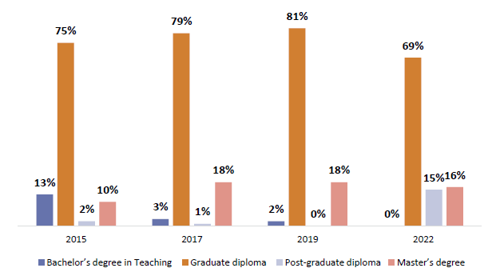

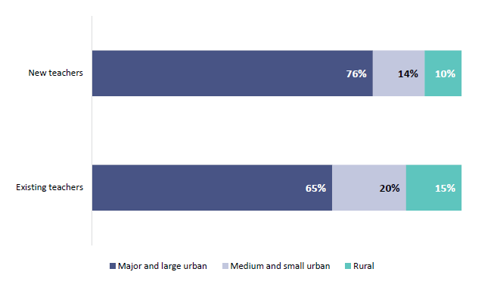

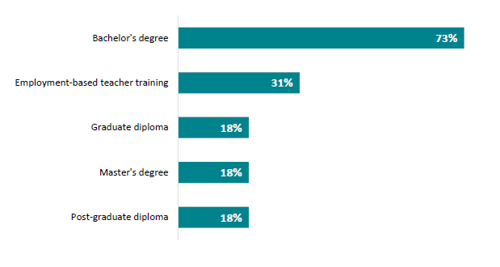

For primary school teachers, the most common pathway into teaching is to complete a three‑year Bachelor’s degree in teaching. Other pathways are a one-year graduate diploma or post-graduate diploma, or a two-year Master’s degree. The post-graduate diploma pathway became available in 2017, and the Master’s degree for primary teaching has been available since 2014. [Education Counts]

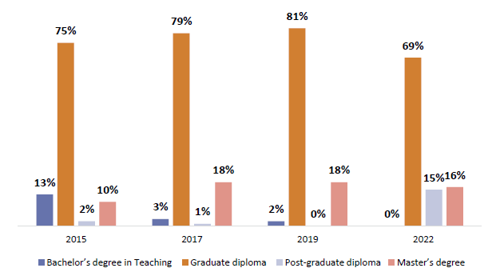

Becoming a secondary teacher requires completing a specialist subject degree at Bachelor level or higher and then a one-year or two-year post graduate teaching qualification. There have been no enrolments in a Bachelor Degree in teaching for secondary teachers since 2019.

Some aspiring teachers study at universities or other tertiary providers like polytechnics, wānanga, or private training establishments (explained in Part 3), and undertake employment‑based(18) or field-based ITE. In employment-based ITE, aspiring teachers learn while being employed by a host school as a member of staff holding a Limited Authority to Teach: Teaching Council of New Zealand. (Limited Authority to Teach enables people without teaching qualifications to teach in positions where there is a need for specialist skills or skills in short supply. It is not a type of practising certificate nor for registered teachers or permanent employment. LAT teachers do not need to have a supervisor. )They may continue to work in the same school on completion of their ITE, as a Provisionally Certificated Teacher. In field-based ITE, the student teacher does not need to be employed at a school.

The main employment-based programme in Aotearoa New Zealand is Ako Mātātupu - Teach First NZ.(19) It provides financial assistance for those people wanting to teach who would have found it difficult financially to study full time.

Ako Mātātupu Teach First NZ offers enrolled students an opportunity to work towards a post-Graduate Diploma in Secondary Teaching while being employed in a secondary school. The programme is two years, rather than one year like other diplomas.

c) How does the registration and certification process work?

Provisional certification

Graduates of ITE programmes register as a teacher with the Teaching Council and apply for a Provisional Practising Certificate, allowing them to teach in a school in Aotearoa New Zealand (‘Provisionally Certificated Teachers’). They need to provide evidence of:

- completing an approved programme

- a commitment to the expectations in the Code of Professional Responsibility (Ngā Tikanga Matatika | The Code is a set of aspirations for professional behaviour, It reflects the expectations teachers and society place on the profession. It is binding on all teachers)

- a commitment to practice te reo and tikanga Māori

- a satisfactory police vet, which includes confirmation of identity.

Holding a Provisional Practising Certificate means that teachers can meet the standards for the teaching profession with support. New teachers can hold the Provisional Practising Certificate for a maximum of five years, though the induction and mentoring period is only two years.

Monitoring progress

Provisionally Certificated Teachers, their mentors, and professional leaders keep a record of progress and evidence of meeting the Standards for the Teaching Profession. The principal monitors the progress of the new teacher and, at the end of the induction and mentoring programme, professional leaders attest to their ability to meet the standards to support an application for a full practising certificate. The Teaching Council decides on issuing full practising certificates for new teachers based on the evidence and judgements supplied by the school.

3) What are the systems and supports for new teachers?

There is a range of support provided for new teachers to develop their capability for the first two years as they begin their career.

After gaining a teaching qualification, graduates apply for a teaching position, through which they complete their provisional period of two years. As Provisionally Certificated Teachers, they complete a structured programme of induction and mentoring, and if they meet the conditions, qualify for a range of supports to develop their capability towards the Standards for the Teaching Profession.(20)

(A Provisional Practising Certificate is issued or renewed for three years and designed to be held for a maximum of five years. Teachers are expected to complete induction and mentoring and gain a full practising certificate within this timeframe. Applying for a Tōmua | Provisional Practising Certificate :: Teaching Council of Aotearoa New Zealand)

(The Teaching of Council is currently reviewing Induction and Mentoring requirements to ensure all new teachers have access to good quality programmes)

Table 2: Elements of support

|

Elements of support |

Who provides this |

What it looks like |

|

Beginning Teacher Allowance (for classroom release time) |

MOE provides to schools for each new teacher they are employing for a minimum of 0.5 full-time teacher equivalent (FTTE).

|

This allowance helps schools release new teachers from teaching duties for the equivalent of one day a week in their first year, and for a half day each week for their second year. Release time allows new teachers to undertake a range of professional learning activities. |

|

Induction and Mentoring programme |

The school employer/professional leader should ensure a formal induction programme is available to each new teacher throughout their first two years. |

This programme provides support for new teachers at the school where they work to meet the Standards. A comprehensive induction programme includes: · welcoming and introducing a new teacher to the context in which they will work · ongoing professional development and support from a range of sources · access to external professional networks · educative mentoring. |

|

Mentor teacher support |

Mentor teachers, who are fully certificated and experienced teachers, plan and supervise an individualised learning programme with a new teacher. The Ministry provides a mentor teacher allowance to assigned mentors. |

Teachers are assigned a mentor, usually within the new teacher’s school or from a nearby school. (If a mentor is not available at their school, for example in small schools, a fully certificated teacher from the local community.) Mentor teachers are selected by the school leader. There is no minimum standard or accreditation for fully certificated teachers to be nominated as mentor teachers. Mentor teachers work closely with new teachers to provide support and supervision for the duration of provisional certification.(21) |

|

Professional learning and development |

A range of internal and external providers or colleagues, driven by the Induction and Mentoring programme. |

Professional learning and development is part of the induction and mentoring, includes formal and informal opportunities for: · observing other teachers and learners in another setting · discussions with other teachers such as senior staff, support staff, specialist classroom teachers or specialist education services · becoming familiar with the teaching resources, records, school policies and procedures · going to courses and meetings inside and outside the school · reflecting on professional learning and applying it to teaching practice. |

|

Other supports

|

Professional leaders and colleagues. |

Professional leaders and colleagues undertake regular wellbeing check-ins of their new teachers and address any concerns raised in a timely way. Professional leaders monitor the progress of the new teacher and examine evidence of meeting the Standards to support teachers to obtain a Full Practising Certificate. |

4) How does Aotearoa New Zealand compare to other countries?

The system to train and support new teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand is comparable to the systems in United Kingdom (UK), Australia, Japan, and Singapore in several ways. These include:

- attracting candidates into teaching

- setting entry requirements for entering ITE

- ensuring quality delivery of ITE programmes

- certifying and hiring new teachers

- supporting new teachers

- fully certifying new teachers

- retaining teachers.

There are some differences on specific requirements for entering ITE and obtaining teaching certification, as well as specific provisions and structure of support. While there is some variation between the different states in Australia, and countries in the United Kingdom (UK) the areas that our system is different from other countries are:

- entry requirements for entering ITE are higher than the UK, but lower than Singapore

- we have a much greater number of ITE providers than Singapore, but fewer than the UK and Australia

- we require more in-classroom practice time than Australia and Singapore, but less than the UK

- we consider graduation from ITE as a criterion to issue provisional certification for new teachers. Some territories in Australia and Japan require additional assessments of teachers’ capability, apart from their ITE graduation, before certifying new teachers

- there is a similar level support for new teachers, but a less structured induction and mentoring programme

- there is a similar process to fully certify teachers, but is less strict than England. In England, new teachers can only go through induction once. If they fail induction, they are not able to move to full registration and be employed in state-run schools.

Table 3 further explains these points of differences.

Table 3: System to train and support new teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand, compared to other countries

|

Process |

Aotearoa New Zealand |

Examples from other OECD countries |

|

Attracting applicants into teaching |

1. Teach NZ scholarships are aimed at attracting teachers into specific areas where there are shortages. In 2023, these were targeted at applicants who: · are planning to teach Science, Technology, or Maths · are planning to teach in ECE or secondary schools · are Māori, Pasifika or planning to teach in bilingual or immersion settings · are from diverse ethnic backgrounds · have previously worked in schools, e.g. teacher aides · are high achieving Māori and Pacific students (the Kupe scholarships). 2. The Secondary School Onsite Training Programme is an alternative pathway to teaching for aspiring secondary teachers. It pays fees and a stipend and aims at attracting career changers into teaching.

|

UK, Australia, and Singapore use scholarships to attract the highest calibre of students in to teaching. Government funded bursaries in the UK target teachers who have quality undergraduate or post graduate degrees. Bursaries are higher for students who have postgraduate degrees in STEM subject or languages. There are also bursaries for undergraduate education study if the teacher also studies mathematics or physics at the same time.(22) Australia has scholarships for high achieving school leavers, mid‑career professionals who want to transition to teaching, and people from diverse backgrounds (including first nations teachers, teachers who have English as a second language, disabled teachers, and teachers from rural, remote, and poorer communities).(23) Singapore pays scholarships to the highest achieving school leavers, including paying to study education in overseas universities.(24) |

|

Number of ITE providers |

There are 87 different ITE programmes, available from 25 different providers. |

In Singapore, all teachers complete either a diploma or degree course at the country’s National Institute of Education at Nanyang Technological University.(25) There are 170 providers accredited to deliver ITE in the UK,(26) and 367 programmes across 48 providers in Australia.(27) |

|

Entry requirements into ITE |

To enter ITE, candidates need to attain University Entrance (UE), which includes minimum 14 credits at NCEA Level 3, 10 credits at NCEA Level 2 or above for Literacy, 10 credits at NCEA Level 1 or above for Numeracy. In 2022, around half of secondary school graduates achieved UE. Those over 20 years of age and without UE need to demonstrate to a provider’s satisfaction that they are able to study at a tertiary level. Some ITE providers have numeracy and literacy tests in place that candidates must pass prior to entry. |

In the UK, the minimum requirement is a Grade 4 in GCSE examinations in English and Maths. Additionally, those who teach students aged three to 11 need a Grade 4 in GCSE examinations in a science subject. In 2022, around three-quarters of secondary school graduates achieved Grade 4 in GCSE.(28) In Singapore, ITE entrants are often selected from the top 30 percent of the secondary school graduating class.(29) |

|

Professional experience placement requirements |

In New Zealand, the minimum placement required is 80 days (16 weeks) for one-year programmes and 120 days (24 weeks) for three or more-year programmes. |

Australia requires 60 days (12 weeks) for one-year programme and 80 days (16 weeks) for three-year programmes.(30) Singapore requires a minimum of 50 days (10 weeks) for one-year programmes and 110 days (22 weeks) for four-year teaching programmes.(31) The UK requires at least 120 days (24 weeks) for one- to three-year programmes, and at least 160 days (32 weeks) for a four-year programme.(32) |

|

Certifying new teachers |

ITE providers ensure that their graduates meet the teaching standards, to award students with a teaching qualification. The Teaching Council provides Provisional Practising Certification based on this qualification. |

In Japan, the Board of Education (BOE) in each province is responsible for certifying teachers. Besides their teaching qualification, the Board hires teachers through an examination process, which includes a written examination, a practical examination, and interviews. There is a one-year probation period for new teachers.(33) In some states and territories in Australia such as in Queensland, several ITE providers complement their qualification with the Graduate Teacher Performance Assessment (GTPA). This assessment is based on the national teacher standards in an “interrelated, authentic way”. This assessment is delivered by the Higher Education Institution; it acts to set a common, established standard in teacher quality across participating institutions.(34) |

|

Induction and mentoring |

New teachers participate in a two-year school-based induction and mentoring programme before being fully certified. Induction and mentoring are designed by the school, and the Teaching Council only provides guidance. The provision of 0.2 release time is given for teachers in their first year of teaching and 0.1 release for their second year of teaching. |

In Japan, the induction period is one year. The Board of Education in each prefecture, who hires new teachers, organises induction training for all new teachers. New teachers receive induction at a base institution, with one assigned supervisor.(35) In England, the induction period is two years. Schools need to assign two roles to support new teachers. There are also organisations (called ‘appropriate bodies’) to independently quality assure the induction at schools. They ensure new teachers receive support and guidance and have regular observation and written feedback on their teaching.(36) |

|

Obtaining a full teaching certificate |

Professional leaders recommend to the Teaching Council whether teachers can be fully certificated, based on evidence from their induction period. Teachers also have to meet ‘satisfactory teaching experience’ requirements. This means they need to have an uninterrupted period of employment of two years in the previous five years. |

In Australia, the requirement for full registration is generally consistent across the country, including a required number of days teaching and a portfolio of evidence of teaching capability. However, the detailed requirement varies across states or territories. For example, Victoria requires 80 teaching days over two years, while Queensland requires 200 teaching days over five years. Teachers themselves collect the portfolio of evidence and a school-based panel assessed that evidence. They recommend teachers to full registration to the relevant authority of that state or territory.(37) In the UK, new teachers can only go through induction once. There are two formal assessments in the middle and at the end of the induction period to demonstrate they meet the Teachers’ Standards. The induction tutors and appropriate bodies oversees the formal assessments. The Teaching Regulation Agency (a central government agency) keeps records of the assessment decision. If new teachers are assessed as failing the induction, they cannot lawfully be employed as a teacher in most state-run schools.(38) |

|

Retaining teachers |

1. The Ministry of Education supports new teachers with the BeTTER jobs programme, which matches new or returning teachers with schools experiencing recruitment or retention challenges. Teachers receive $10,000 over two years of employment and schools receive $20,000 over two years. 2. Voluntary Bonding Scheme (VBS) encourages teachers to teach in certain areas of need by providing them with a stipend. |

In Australia, teachers receiving scholarships in ITE are bonded to the profession for the same length of time they studied.(39) In Singapore, recipients of scholarships are bonded to the profession for a period of four to six years.(40) |

5) What do we mean by ‘prepared to teach’?

When new teachers are prepared to teach, they are equipped with the essential knowledge and skills they need to be effective teachers. They can draw on this to maximise outcomes for their students.

The Teaching Council requirements for ITE programme approval state that the programme must be ‘structured in such a way, and contain such core elements, that ensures that graduates are able to demonstrate that they meet the Standards (in a supported environment)’.(41)

Research shows that new teachers’ performance in the classroom is positively linked to their feelings of preparedness. When new teachers feel prepared, this has a positive impact on a range of student outcomes including their learning motivation and involvement in class activities, achievement, and personal management skills, like efforts shown when faced with challenges.(42)

When we talk about new teachers feeling ‘prepared to teach’, we are talking about how confident new teachers are in their ability to do what is required of them as teachers. Teachers’ perception of their own preparedness is the measure used in studies such as the TALIS (2018). We break this down into their readiness in a range of professional practice areas and subject areas (illustrated in Table 4 below). We used the six standards and components of effective teaching standards from the Teaching Council’s Standards for the Teaching Profession to identify the professional practices. The curriculum also has competencies that are expected to be taught.

Table 4: Professional practice and subject knowledge areas

|

Professional practice areas |

Subject knowledge (primary only) |

|

1. Professional knowledge of teaching strategies 2. Planning lessons 3. Adapting teaching strategies for learners 4. Using assessments to inform teaching 5. Managing classroom behaviour 6. Working with parents and whānau 7. Creating an engaging environment 8. Working with other teachers and teacher aides 9. Giving effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi in teaching |

1. English 2. Te reo Māori 3. The arts 4. Health and physical education 5. Teaching languages 6. Mathematics and statistics 7. Science 8. Social sciences 9. Technology

|

Conclusion

There are several steps involved in becoming a new teacher in Aotearoa New Zealand. The key aspects include gaining a teaching qualification, completing an ITE programme at an approved provider, followed by completing a two-year provisional practice period in schools.

The ITE programme and the provisional period are designed to avoid theory and practice being separated. Both phases involve elements of assessment to ensure new teachers are competent and can meet the professional standards. New teachers continue to learn and develop their skills in teaching throughout the provisional period, and their professional leader attests to their suitability for full certification as a teacher.

New teachers’ feeling of preparedness is linked to how well they teach. New teachers’ confidence in their preparation has a positive impact on student outcomes in their class.

Aotearoa New Zealand needs good teachers to enable all students to achieve. Teaching is a profession that needs a high level of skill to do well. As our population grows and the teaching workforce ages, demand for new teachers is high. It is therefore important that every school has well-qualified, diverse, and competent teachers to ensure students have the best possible learning outcomes.

To become a teacher in Aotearoa New Zealand, prospective teachers undertake Initial Teacher Education (ITE) and gain a teaching qualification through an approved provider. A wide range of programmes, providers, and qualifications are available.

After registering to become a new teacher, they are issued a Provisional Practising Certificate. During this provisional period they receive a range of support and are expected to progress towards demonstrating the Standards for the Teaching Profession.

The Standards for the Teaching Profession| Ngā Paerewa are made up of six standards that describe what high quality teaching practice looks like. The Standards is issued by the Teaching Council and apply to all teachers. Teachers need to demonstrate they meet the Standards to be certificated by the Teaching Council to teach.

This section sets out:

- why ERO focused on new teachers

- how you become a new teacher in Aotearoa New Zealand

- the systems and supports for new teachers

- how Aotearoa New Zealand compares to other countries’ teacher education pathways

- what we mean by being ‘prepared to teach’.

1) Why has ERO focused on new teachers?

The teaching role is complex.

The teaching role in schools is complex, and there are many demands on teachers. Teachers need to be able to draw on their professional knowledge of teaching strategies to plan and deliver lessons in a way that engages students. They need to use what they know about learners, including from assessment, understanding of their parents and culture, and knowing about any disabilities or impairments, to adapt the way they apply these strategies. Alongside this, teachers have to manage classroom behaviour, work with parents and whānau, and other school staff.

We have a significant need to strengthen the quality of teaching in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Student achievement in Aotearoa New Zealand is a concern. Recent PISA results show an overall downward trend in student achievement in maths, reading and science since 2006.(1) Aotearoa New Zealand’s national performance monitoring study (the National Monitoring Study of Student Achievement, NMSSA) also shows declining achievement in English,(2) but no significant changes in maths(3) or science.(4)

Although NMSSA shows achievement staying steady for maths and science, and most Year 4 students are achieving at or above the curriculum level, significantly fewer Year 8 students achieve at the expected level (42 percent in maths, and only 20 percent in science).

Around one in 10 children in Aotearoa New Zealand are disabled. Unfortunately, ERO found in 2022 that over half of school teachers lack confidence in teaching disabled learners.(5) A recent ERO report also shows disruptive behaviour in classrooms is increasing, and this has a negative impact on students’ learning.(6) Ensuring we have teachers that demonstrate effective practice is essential if we are to make the improvements needed.

We have an ageing teaching workforce, and demand for teachers will increase in the next five years.

Our teaching workforce is ageing. There were 72,950 teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand primary and secondary schools in 2022. Nearly 30 percent of these teachers are 55-years-old or older.

The Ministry of Education (the Ministry) predicts that, although demand for primary teachers will decrease into 2025, demand for secondary teachers will grow. If the retention rate and intake of teachers continues to be low, there will be a shortage of up to 620 secondary school teachers. The Ministry also anticipates an ongoing need to grow supply in some subjects and in certain parts of the country(7).

(The teacher demand and supply data has limitations in that specific areas of needs cannot be definitively identified, for example, demand and supply in different regions.)

The Government has a strong focus on improving student outcomes.

The Government’s ‘Teaching the basics brilliantly’ plan for education places a stronger focus on ensuring best practice, building off evidence, and calls for stronger rigour in classroom teaching. To do this, the Government draws on research from the last two decades, into the science of teaching and learning.(8)

The Government education plan signals a shift to a more strongly knowledge rich curriculum with learning less likely being left to chance, and places an increasing emphasis on ‘subject specific pedagogies’ rather than general pedagogical approaches.

To deliver on this, initial teacher education needs to prepare new teachers to be at the forefront of the changes.

Teachers are the most important in-school contributor to student outcomes.

Effective and high-quality teaching has a large impact on student outcomes.(9)(10) Research has found that students starting out at a similar level of achievement could be as many as 53 percentiles apart after three years, depending on the capabilities of their teacher.(11)

There is increasing international evidence about what effective preparation for teaching involves. New teachers learn from observing high quality teaching, receiving frequent and useful feedback, and interacting with a collaborative teaching community. For some, the quality of their placement experience makes the difference between passing and failing a course,(12) and their future success as teachers.

Initial teacher education alone cannot make the transformation to teaching and learning we need, to see the improvements we want. It is important that all parts of the education system work effectively to deliver a high-quality teaching workforce, and high-quality teaching and learning in our classrooms. Ensuring new teachers are confident and well-equipped to teach is an important contributing component to this.

2) How do you become a new teacher in Aotearoa New Zealand?

There are four steps to becoming a teacher in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Teachers must complete an ITE qualification before they can register as a teacher. They then complete a two-year programme of induction and mentoring, before being eligible for full certification as a teacher.

a) What are the components of ITE?

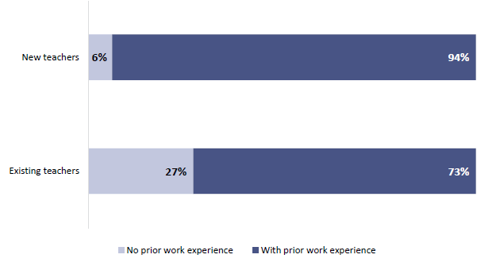

There are 87 different ITE programmes, available from 25 approved providers.(13) These providers include universities, institutes of technology, polytechnics, wānanga, and private training establishments. The full list of providers is included in Appendix 2.