Our featured insights

Read Online

Summary

This guide sets out the key practices for leaders to support the effective implementation of the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy. It shares the insights of what works well and what things to consider when implementing this policy. These insights draw on the established evidence around cell phone use in classrooms and the effective strategies being used by schools in Aotearoa New Zealand. The guide provides practical actions school leaders can take, and links to other useful resources and tools.

This guide sets out the key practices for leaders to support the effective implementation of the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy. It shares the insights of what works well and what things to consider when implementing this policy. These insights draw on the established evidence around cell phone use in classrooms and the effective strategies being used by schools in Aotearoa New Zealand. The guide provides practical actions school leaders can take, and links to other useful resources and tools.

Introduction to this good practice guide

Cell phone use can have a big impact on our students. New Zealand is one of many countries working to limit cell phone use in schools. This guide sets out four effective practices for school leaders to implement the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy in their school, as required by the Government. This guide also shares early insights about what works well in schools, gathered from ERO’s review of the implementation of the current cell phone policy.

Cell phone use can have a big impact on our students. New Zealand is one of many countries working to limit cell phone use in schools. This guide sets out four effective practices for school leaders to implement the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy in their school, as required by the Government. This guide also shares early insights about what works well in schools, gathered from ERO’s review of the implementation of the current cell phone policy.

What does this guide cover?

Managing student phone use can help New Zealand tackle some of the big problems facing our students. In particular, it can help improve achievement and behaviour, and reduce the risk of harm from social media.

Education Review Office (ERO), from the report Do not disturb: A review of removing cell phones from New Zealand’s classrooms (2025)

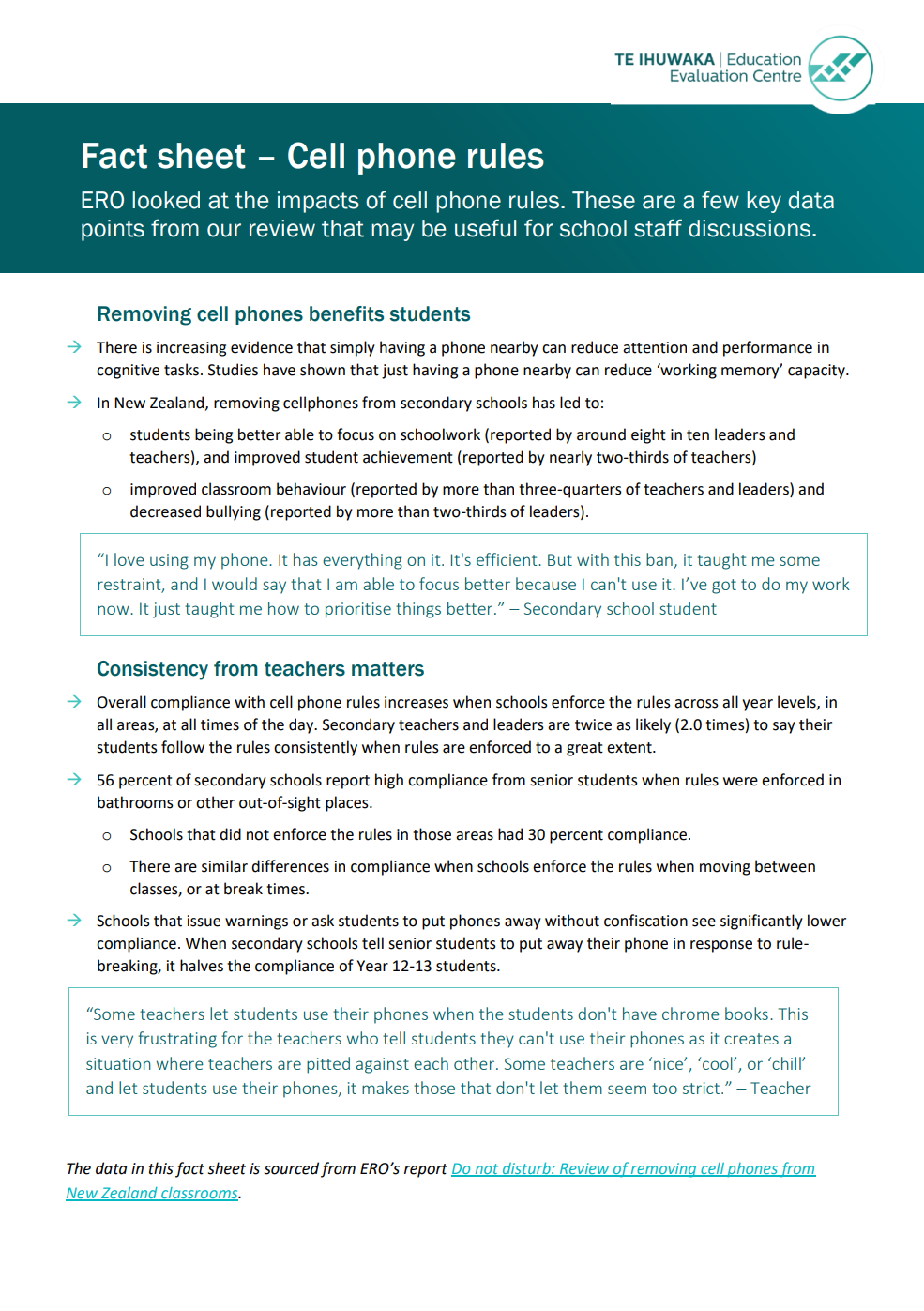

Globally, there is an increasing recognition of the harm that student phone use in schools can cause, such as distracting students from learning, and reducing their social interaction. There is also increasing evidence that simply having a phone nearby can reduce attention and performance in cognitive tasks. Policies like cell phone bans can help mitigate distractions, but effective enforcement and other strategies are needed for focused learning environments.

In 2024, the Government introduced the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy in New Zealand schools. School leaders have used a range of strategies to implement the policy, and have also encountered some challenges. This guide draws from what we learnt from schools in New Zealand, as well as the established evidence base, focusing on practices and actions that work. It also provides practical examples from schools around the country.

DID YOU KNOW?

New Zealand students reported the fifth highest level of distraction due to digital devices in recent PISA results (2022). Almost half (46 percent) of students get distracted using digital devices in every or most maths lessons.

Managing student phone use can help New Zealand tackle some of the big problems facing our students. In particular, it can help improve achievement and behaviour, and reduce the risk of harm from social media.

Education Review Office (ERO), from the report Do not disturb: A review of removing cell phones from New Zealand’s classrooms (2025)

Globally, there is an increasing recognition of the harm that student phone use in schools can cause, such as distracting students from learning, and reducing their social interaction. There is also increasing evidence that simply having a phone nearby can reduce attention and performance in cognitive tasks. Policies like cell phone bans can help mitigate distractions, but effective enforcement and other strategies are needed for focused learning environments.

In 2024, the Government introduced the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy in New Zealand schools. School leaders have used a range of strategies to implement the policy, and have also encountered some challenges. This guide draws from what we learnt from schools in New Zealand, as well as the established evidence base, focusing on practices and actions that work. It also provides practical examples from schools around the country.

DID YOU KNOW?

New Zealand students reported the fifth highest level of distraction due to digital devices in recent PISA results (2022). Almost half (46 percent) of students get distracted using digital devices in every or most maths lessons.

Who is this guide for?

This guide is intended to support school leaders to effectively implement ‘Phones Away for the Day’ in their school. It is designed to provide practical guidance, so school leaders can effectively implement this policy requirement. It will also be of interest to school boards and classroom teachers, who contribute to effective policy implementation in schools.

This guide is intended to support school leaders to effectively implement ‘Phones Away for the Day’ in their school. It is designed to provide practical guidance, so school leaders can effectively implement this policy requirement. It will also be of interest to school boards and classroom teachers, who contribute to effective policy implementation in schools.

How to use this guide

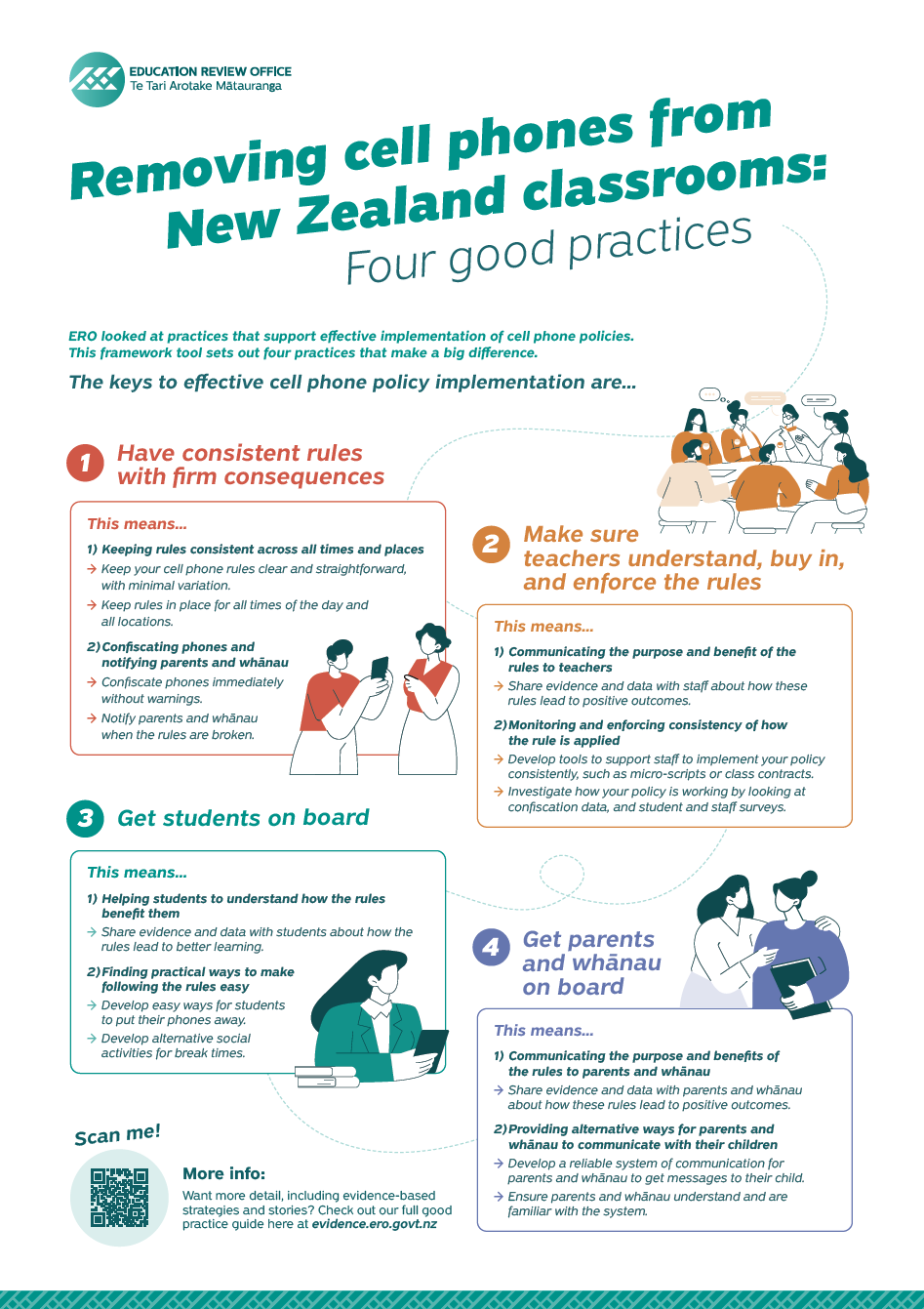

This guide outlines four practice areas that have proven successful for schools in New Zealand to implement their ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policies:

1) Have consistent rules with firm consequences

2) Make sure teachers understand, buy in, and enforce the rules

3) Get students on board

4) Get parents and whānau on board

Each of the practices are supported by real-life examples and reflective questions to support high-quality implementation of the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy.

DID YOU KNOW?

Most secondary teachers (77 percent) and leaders (78 percent) say the new cell phone policy has improved student behaviour in the classroom.

This good practice guide is supported by findings from ERO’s national review report Do not disturb: Review of removing cell phones from New Zealand’s classrooms and acts as a companion resource. You can find the full report here.

This guide outlines four practice areas that have proven successful for schools in New Zealand to implement their ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policies:

1) Have consistent rules with firm consequences

2) Make sure teachers understand, buy in, and enforce the rules

3) Get students on board

4) Get parents and whānau on board

Each of the practices are supported by real-life examples and reflective questions to support high-quality implementation of the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy.

DID YOU KNOW?

Most secondary teachers (77 percent) and leaders (78 percent) say the new cell phone policy has improved student behaviour in the classroom.

This good practice guide is supported by findings from ERO’s national review report Do not disturb: Review of removing cell phones from New Zealand’s classrooms and acts as a companion resource. You can find the full report here.

Summary of key practices

Have consistent rules with firm consequences

We can ensure that we have consistent rules with firm consequences by:

1) Keeping rules consistent across all times and places

2) Confiscating phones and notifying parents and whānau

Make sure teachers understand, buy in, and enforce the rules

We can ensure that teachers understand, buy in, and enforce the rules by:

1) Communicating the purpose and benefit of the rules to teachers

2) Monitoring and enforcing consistency of how the rule is applied

Get students on board

We can get students on board by:

1) Helping students to understand how ‘Phones Away for the Day’ benefits them

2) Finding practical ways to make following the rules easy

Get parents and whānau on board

We can get parents and whānau on board by:

1) Communicating the purpose and benefits of the rules to parents and whānau

2) Providing alternative ways for parents and whānau to communicate with their children

Have consistent rules with firm consequences

We can ensure that we have consistent rules with firm consequences by:

1) Keeping rules consistent across all times and places

2) Confiscating phones and notifying parents and whānau

Make sure teachers understand, buy in, and enforce the rules

We can ensure that teachers understand, buy in, and enforce the rules by:

1) Communicating the purpose and benefit of the rules to teachers

2) Monitoring and enforcing consistency of how the rule is applied

Get students on board

We can get students on board by:

1) Helping students to understand how ‘Phones Away for the Day’ benefits them

2) Finding practical ways to make following the rules easy

Get parents and whānau on board

We can get parents and whānau on board by:

1) Communicating the purpose and benefits of the rules to parents and whānau

2) Providing alternative ways for parents and whānau to communicate with their children

1 - Have consistent rules with firm consequences

It’s best to keep phone rules simple, clear, and consistent. When this approach is combined with firm consequences, schools see high compliance.

Why do consistent rules and firm consequences matter?

Consistency is key to get a rule to stick. When rules are predictable and widely-held, everyone is on the same page. There is more consistent enforcement from teachers and higher compliance from students. In our review we found that many schools apply the rule differently across times of the day, physical spaces, and year levels, but we found that having a consistent approach matters. Consistency increases effective implementation.

DID YOU KNOW?

Currently only just over half (53 percent) of secondary school students consistently follow their school’s phone rules.

How can you support your school to have consistent rules with firm consequences?

School leaders can do this by:

1) keeping rules consistent across all times and places

2) confiscating phones and notifying parents and whānau.

It’s best to keep phone rules simple, clear, and consistent. When this approach is combined with firm consequences, schools see high compliance.

Why do consistent rules and firm consequences matter?

Consistency is key to get a rule to stick. When rules are predictable and widely-held, everyone is on the same page. There is more consistent enforcement from teachers and higher compliance from students. In our review we found that many schools apply the rule differently across times of the day, physical spaces, and year levels, but we found that having a consistent approach matters. Consistency increases effective implementation.

DID YOU KNOW?

Currently only just over half (53 percent) of secondary school students consistently follow their school’s phone rules.

How can you support your school to have consistent rules with firm consequences?

School leaders can do this by:

1) keeping rules consistent across all times and places

2) confiscating phones and notifying parents and whānau.

1) Keeping rules consistent across all times and places

When students know that the cell phone rule is applied inconsistently, they are more likely to try to find ways to use their phones. Most primary schools apply a consistent rule across all year levels and times of the day, whereas some secondary schools have different rules. These rules can change across times of the day, areas of the school, and age groups. ‘Phones Away for the Day’ requires all students to have their phones away for the entire day, including break times. Enforcing the policy during break times can be challenging in secondary settings when students still have access to their cell phones. Developing ways to enforce ‘Phones Away for the Day’ during break times is important for consistency.

Enforcing the rules across more areas in the school results in higher compliance from secondary students. For instance, just over a third (35 percent) of secondary schools that enforce the rules in less than half of places have high compliance from senior students. In contrast, just over six in ten schools (62 percent) that enforce rules across four or more places – such as classrooms, hallways, school trips, bathrooms, and break times – see high compliance from secondary students.

“The students are sneaky – they use their phones all the time, like in bathrooms and in class time, but the teachers never catch them.”

- STUDENT

“…As soon as there is a relief teacher or a change of day structure (sports days etc.), the phones rules are not implemented properly.”

- BOARD MEMBER

“The guidance from the school is clear. However, it is not enforced consistently in different classes. Also, the school policy is no phones ‘in class’ rather than no phones ‘during the school day’. I think this approach to no phones ‘in class’ makes it harder for my child to keep off their phone in class… If school was ‘no phone at school’ then the impulse to be on their phone at school would be less/the habit would not be there…”

- PARENT/WHĀNAU

Designing a ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy for your school that minimises variability in the way cell phones are accessed and used is key to achieving high compliance.

DID YOU KNOW?

Around nine in ten primary (93 percent) and secondary teachers (88 percent) report that having consistent rules across year levels helps.

1) Keeping rules consistent across all times and places

When students know that the cell phone rule is applied inconsistently, they are more likely to try to find ways to use their phones. Most primary schools apply a consistent rule across all year levels and times of the day, whereas some secondary schools have different rules. These rules can change across times of the day, areas of the school, and age groups. ‘Phones Away for the Day’ requires all students to have their phones away for the entire day, including break times. Enforcing the policy during break times can be challenging in secondary settings when students still have access to their cell phones. Developing ways to enforce ‘Phones Away for the Day’ during break times is important for consistency.

Enforcing the rules across more areas in the school results in higher compliance from secondary students. For instance, just over a third (35 percent) of secondary schools that enforce the rules in less than half of places have high compliance from senior students. In contrast, just over six in ten schools (62 percent) that enforce rules across four or more places – such as classrooms, hallways, school trips, bathrooms, and break times – see high compliance from secondary students.

“The students are sneaky – they use their phones all the time, like in bathrooms and in class time, but the teachers never catch them.”

- STUDENT

“…As soon as there is a relief teacher or a change of day structure (sports days etc.), the phones rules are not implemented properly.”

- BOARD MEMBER

“The guidance from the school is clear. However, it is not enforced consistently in different classes. Also, the school policy is no phones ‘in class’ rather than no phones ‘during the school day’. I think this approach to no phones ‘in class’ makes it harder for my child to keep off their phone in class… If school was ‘no phone at school’ then the impulse to be on their phone at school would be less/the habit would not be there…”

- PARENT/WHĀNAU

Designing a ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy for your school that minimises variability in the way cell phones are accessed and used is key to achieving high compliance.

DID YOU KNOW?

Around nine in ten primary (93 percent) and secondary teachers (88 percent) report that having consistent rules across year levels helps.

2) Confiscating phones and notifying parents and whānau

Schools that apply stronger consequences when students do not follow the rules see a higher level of compliance. Secondary students are twice as likely to follow the rules consistently when schools strictly monitor and enforce the rules. In primary schools, students are three times more likely to be consistently compliant.

We heard from our key informants that schools with strong foundational policies around behaviour or attendance tend to have strong uptake and enforcement of the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy. Similarly, we heard that strong leadership drives effective implementation, with careful planning to mitigate non-compliance in out-of-sight places.

Secondary schools that respond to rule-breaking with stronger consequences appear to have higher levels of compliance. When schools confiscate phones and notify parents and whānau, students are more likely to comply.

DID YOU KNOW?

Secondary schools that confiscate phones have higher compliance from senior secondary students. Just under four in ten schools (39 percent) have high compliance from Year 12-13 students who use the consequence, compared to just over two in ten schools (21 percent) that do not.

DID YOU KNOW?

Parent and whānau notification increases the likelihood of secondary students’ compliance by 1.5 times.

A softer approach to rule-breaking appears to be less effective for senior students. Schools that only issue warnings, or ask students to put phones away without confiscation, see significantly lower compliance. Less than half as many senior students follow the rules.

DID YOU KNOW?

Secondary schools that immediately confiscate phones as a consequence not only have better compliance, they are almost twice as likely to report that behaviour (2.0 times), focus (2.1 times), and achievement (1.9 times) improves.

2) Confiscating phones and notifying parents and whānau

Schools that apply stronger consequences when students do not follow the rules see a higher level of compliance. Secondary students are twice as likely to follow the rules consistently when schools strictly monitor and enforce the rules. In primary schools, students are three times more likely to be consistently compliant.

We heard from our key informants that schools with strong foundational policies around behaviour or attendance tend to have strong uptake and enforcement of the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy. Similarly, we heard that strong leadership drives effective implementation, with careful planning to mitigate non-compliance in out-of-sight places.

Secondary schools that respond to rule-breaking with stronger consequences appear to have higher levels of compliance. When schools confiscate phones and notify parents and whānau, students are more likely to comply.

DID YOU KNOW?

Secondary schools that confiscate phones have higher compliance from senior secondary students. Just under four in ten schools (39 percent) have high compliance from Year 12-13 students who use the consequence, compared to just over two in ten schools (21 percent) that do not.

DID YOU KNOW?

Parent and whānau notification increases the likelihood of secondary students’ compliance by 1.5 times.

A softer approach to rule-breaking appears to be less effective for senior students. Schools that only issue warnings, or ask students to put phones away without confiscation, see significantly lower compliance. Less than half as many senior students follow the rules.

DID YOU KNOW?

Secondary schools that immediately confiscate phones as a consequence not only have better compliance, they are almost twice as likely to report that behaviour (2.0 times), focus (2.1 times), and achievement (1.9 times) improves.

Real-life example: Removing students’ access to phones in a secondary school environment

Removing students’ access to phones has a high impact on compliance. We see this blanket approach used widely across the primary sector where there is a much higher compliance rate. In one medium-sized urban secondary school, they have achieved the same impact by using magnetic pouches. Students start the day in their form class, and their teacher supervises the students locking their phones into pouches. High powered magnets are mounted in lock boxes around the school and are unlocked at the end of the day. Students can release their phones themselves as they leave the school grounds. This school’s leader describes the difference between pre cell phone policy and post as “chalk and cheese”. They have seen less phone use and a greater uptake of lunchtime activities.

Another medium-sized urban secondary school uses magnetic pouches for confiscating phones during class and break times. This school purchases two magnetic pouches for all staff members. When staff are on duty at break times, they have their magnetic pouches with them. If they see that a student has their phone out, they place the phone inside the pouch, seal it, and return the pouch to the student. At the end of the day, the student goes to the office to release their phone. The office staff record the infringement and return the magnetic pouch to the teacher’s pigeon hole (pouches are numbered so they know which teacher has made the confiscation). Teachers use the same process for confiscating phones in their classrooms. This means the school is not liable for confiscated phones, as the student holds on to their phone.

Real-life example: Developing a system of increasing consequences

In many of the schools we talked to, leaders, teachers, and students described having a system of increasing consequences to respond to cell phone use. We heard that this ensures that responses are consistent and fair.

At one large urban secondary school, leaders have developed a system that focuses on increasing consequences. The first strike is a verbal warning from the classroom teacher. After that, the phone is confiscated and sent to the main office for the student to collect at the end of the day. This strike is recorded in the school’s student management system. Office staff track the number of confiscations and alert the dean and parents and whānau when students reach their next strike. If students continue to have their phone confiscated, they have a meeting with their parents and whānau and a member of the senior leadership team to find a way forward.

We heard that this approach is effective because it helps students understand the consequences of their actions and gives them multiple opportunities to practice effective self-management.

Real-life example: Removing students’ access to phones in a secondary school environment

Removing students’ access to phones has a high impact on compliance. We see this blanket approach used widely across the primary sector where there is a much higher compliance rate. In one medium-sized urban secondary school, they have achieved the same impact by using magnetic pouches. Students start the day in their form class, and their teacher supervises the students locking their phones into pouches. High powered magnets are mounted in lock boxes around the school and are unlocked at the end of the day. Students can release their phones themselves as they leave the school grounds. This school’s leader describes the difference between pre cell phone policy and post as “chalk and cheese”. They have seen less phone use and a greater uptake of lunchtime activities.

Another medium-sized urban secondary school uses magnetic pouches for confiscating phones during class and break times. This school purchases two magnetic pouches for all staff members. When staff are on duty at break times, they have their magnetic pouches with them. If they see that a student has their phone out, they place the phone inside the pouch, seal it, and return the pouch to the student. At the end of the day, the student goes to the office to release their phone. The office staff record the infringement and return the magnetic pouch to the teacher’s pigeon hole (pouches are numbered so they know which teacher has made the confiscation). Teachers use the same process for confiscating phones in their classrooms. This means the school is not liable for confiscated phones, as the student holds on to their phone.

Real-life example: Developing a system of increasing consequences

In many of the schools we talked to, leaders, teachers, and students described having a system of increasing consequences to respond to cell phone use. We heard that this ensures that responses are consistent and fair.

At one large urban secondary school, leaders have developed a system that focuses on increasing consequences. The first strike is a verbal warning from the classroom teacher. After that, the phone is confiscated and sent to the main office for the student to collect at the end of the day. This strike is recorded in the school’s student management system. Office staff track the number of confiscations and alert the dean and parents and whānau when students reach their next strike. If students continue to have their phone confiscated, they have a meeting with their parents and whānau and a member of the senior leadership team to find a way forward.

We heard that this approach is effective because it helps students understand the consequences of their actions and gives them multiple opportunities to practice effective self-management.

Reflective questions:

- How consistent is our cell phone policy across all year levels, times of day, and school spaces? What variability might be undermining student compliance?

- Are the consequences for breaking the cell phone rules clearly defined, predictable, and consistently enforced by all staff? How do we know?

- What foundational policies (e.g., behaviour, attendance) already support a culture of compliance with important rules? How can we leverage these to strengthen phone rule enforcement?

- How can we strategically plan for and monitor ‘out-of-sight’ spaces and times where non-compliance is more likely to occur?

Reflective questions:

- How consistent is our cell phone policy across all year levels, times of day, and school spaces? What variability might be undermining student compliance?

- Are the consequences for breaking the cell phone rules clearly defined, predictable, and consistently enforced by all staff? How do we know?

- What foundational policies (e.g., behaviour, attendance) already support a culture of compliance with important rules? How can we leverage these to strengthen phone rule enforcement?

- How can we strategically plan for and monitor ‘out-of-sight’ spaces and times where non-compliance is more likely to occur?

2 - Make sure teachers understand, buy in, and enforce the rules

Ensuring all staff are supporting and applying the cell phone rules in the same way is essential for smooth implementation of the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy.

Why does making sure teachers understand, buy in, and enforce the rules matter?

Schools that have high compliance with the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy report a range of positive outcomes. These include students’ increased focus in the classroom and greater participation in breaktime activities. Primary schools, where students have fewer teacher changes throughout the day, have less variability in the way the rule is applied, which contributes to their higher compliance.

In secondary schools, when teachers have a shared approach to supporting the cell phone rules, student achievement, ability to focus on schoolwork, and classroom behaviour improves, and bullying reduces. Consistent teacher enforcement is key to successful implementation of the policy.

DID YOU KNOW?

When secondary teachers support the school’s cell phone rules to a great extent, schools are over twice as likely (2.2 times) to see improvements in students’ ability to focus on schoolwork. Similarly, with teachers’ support, schools are over one and a half times more likely (1.7 times) to report that student achievement has improved.

DID YOU KNOW?

In primary schools, students are three times as likely (3.1 times) to have high compliance when rules are enforced strictly.

How can you support your teachers to understand, buy in, and enforce the rules?

School leaders scan do this by:

1) communicating the purpose and benefit of the rules to teachers

2) monitoring and enforcing consistency of how the rule is applied.

Ensuring all staff are supporting and applying the cell phone rules in the same way is essential for smooth implementation of the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy.

Why does making sure teachers understand, buy in, and enforce the rules matter?

Schools that have high compliance with the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy report a range of positive outcomes. These include students’ increased focus in the classroom and greater participation in breaktime activities. Primary schools, where students have fewer teacher changes throughout the day, have less variability in the way the rule is applied, which contributes to their higher compliance.

In secondary schools, when teachers have a shared approach to supporting the cell phone rules, student achievement, ability to focus on schoolwork, and classroom behaviour improves, and bullying reduces. Consistent teacher enforcement is key to successful implementation of the policy.

DID YOU KNOW?

When secondary teachers support the school’s cell phone rules to a great extent, schools are over twice as likely (2.2 times) to see improvements in students’ ability to focus on schoolwork. Similarly, with teachers’ support, schools are over one and a half times more likely (1.7 times) to report that student achievement has improved.

DID YOU KNOW?

In primary schools, students are three times as likely (3.1 times) to have high compliance when rules are enforced strictly.

How can you support your teachers to understand, buy in, and enforce the rules?

School leaders scan do this by:

1) communicating the purpose and benefit of the rules to teachers

2) monitoring and enforcing consistency of how the rule is applied.

1) Communicating the purpose and benefit of the rules to teachers

The evidence is clear that students benefit from an environment that has a high compliance with the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy. The evidence is also clear that rules are easier to enforce and sustain in an environment where all teachers are applying it in the same way. Students are more likely to perceive the rules as unfair – and to perceive their teachers negatively – when not all teachers are working in the same way. It is important to share this data with teachers, so they understand the need for a cohesive and consistent approach.

“Some teachers let students use their phones when the students don’t have chrome books. This is very frustrating for the teachers who tell students they can’t use their phones as it creates a situation where teachers are pitted against each other. Some teachers are ‘nice’, ‘cool’, or ‘chill’ and let students use their phones, it makes those that don’t let them seem too strict.”

- TEACHER FACT SHEET FOR TEACHERS

Want some key data points to share with teachers?

Click here for a printable one-pager: fact sheet

1) Communicating the purpose and benefit of the rules to teachers

The evidence is clear that students benefit from an environment that has a high compliance with the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy. The evidence is also clear that rules are easier to enforce and sustain in an environment where all teachers are applying it in the same way. Students are more likely to perceive the rules as unfair – and to perceive their teachers negatively – when not all teachers are working in the same way. It is important to share this data with teachers, so they understand the need for a cohesive and consistent approach.

“Some teachers let students use their phones when the students don’t have chrome books. This is very frustrating for the teachers who tell students they can’t use their phones as it creates a situation where teachers are pitted against each other. Some teachers are ‘nice’, ‘cool’, or ‘chill’ and let students use their phones, it makes those that don’t let them seem too strict.”

- TEACHER FACT SHEET FOR TEACHERS

Want some key data points to share with teachers?

Click here for a printable one-pager: fact sheet

2) Monitoring and enforcing consistency of how the rule is applied

Teachers consistently told us they welcomed the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy, as it strengthens and legitimises their existing efforts to limit phone use and improve student focus. Before the requirement, many schools had localised rules in place, but enforcement was often undermined by inconsistent support from parents and whānau or leadership. We heard that national policies can help reduce conflict between teachers and students over phone use when teachers are supported to implement the policy consistently. Minimising the variations in the way the policy is applied, and keeping it straightforward for staff, contributes to this.

Monitoring how the policy is being applied within your school context ensures a greater level of consistency, which reduces the potential frustrations that staff and students face.

DID YOU KNOW?

Secondary students are twice as likely (2.0 times) to follow the rules consistently when schools strictly monitor and enforce the rules.

When secondary schools enforce the rules to a great extent, they are almost twice as likely (1.8 times) to see improvements in student behaviour in the classroom and reduced bullying (1.9 times).

2) Monitoring and enforcing consistency of how the rule is applied

Teachers consistently told us they welcomed the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy, as it strengthens and legitimises their existing efforts to limit phone use and improve student focus. Before the requirement, many schools had localised rules in place, but enforcement was often undermined by inconsistent support from parents and whānau or leadership. We heard that national policies can help reduce conflict between teachers and students over phone use when teachers are supported to implement the policy consistently. Minimising the variations in the way the policy is applied, and keeping it straightforward for staff, contributes to this.

Monitoring how the policy is being applied within your school context ensures a greater level of consistency, which reduces the potential frustrations that staff and students face.

DID YOU KNOW?

Secondary students are twice as likely (2.0 times) to follow the rules consistently when schools strictly monitor and enforce the rules.

When secondary schools enforce the rules to a great extent, they are almost twice as likely (1.8 times) to see improvements in student behaviour in the classroom and reduced bullying (1.9 times).

Real-life example: Embedding your cell phone rules into your school values and ways of working

One large secondary school in a diverse urban environment got staff on board by connecting their ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy to Tier One of their positive culture for learning programme (PC4L). This culture was developed in line with the school values, and the cell phone policy was implemented as part of this larger body of work. Staff have received professional development on how to create this consistent culture across the school and how they will set and maintain these expectations. This has helped the policy to stay ‘on top’ for staff. They have clearly documented these expectations as their ‘way of working’ and staff understand that everyone is responsible for working together to achieve this.

Real-life example: Embedding your cell phone rules into your school values and ways of working

One large secondary school in a diverse urban environment got staff on board by connecting their ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy to Tier One of their positive culture for learning programme (PC4L). This culture was developed in line with the school values, and the cell phone policy was implemented as part of this larger body of work. Staff have received professional development on how to create this consistent culture across the school and how they will set and maintain these expectations. This has helped the policy to stay ‘on top’ for staff. They have clearly documented these expectations as their ‘way of working’ and staff understand that everyone is responsible for working together to achieve this.

Reflective questions:

How clearly have we communicated the purpose and positive impacts of the cell phone policy to our teaching staff? Have we built collective buy-in?

Would it help to share clear evidence with teachers, about the impacts of cell phone use in schools? ERO has prepared a printable fact sheet here: fact sheet

To what extent is the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy being applied consistently by all teachers? Are their differences across year levels or departments? How do we know?

How are we supporting teachers to implement the policy confidently and cohesively? Would it be useful to discuss or model useful ways to talk to students about the rule?

Reflective questions:

How clearly have we communicated the purpose and positive impacts of the cell phone policy to our teaching staff? Have we built collective buy-in?

Would it help to share clear evidence with teachers, about the impacts of cell phone use in schools? ERO has prepared a printable fact sheet here: fact sheet

To what extent is the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy being applied consistently by all teachers? Are their differences across year levels or departments? How do we know?

How are we supporting teachers to implement the policy confidently and cohesively? Would it be useful to discuss or model useful ways to talk to students about the rule?

Discussion points for staff meetings

We found that sharing evidence of impact with teachers is an effective motivator to change their practice. Below is some key research that may be useful to share with staff:

Why is teacher support important?

- When secondary teachers support the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy to a ‘great extent’, schools are over twice as likely (2.2 times) to see improvements in students’ ability to focus on schoolwork, and one and a half times more likely (1.7 times) to report that student achievement has improved.

- Strong teacher enforcement is key to improving student outcomes. Student behaviour in the classroom and bullying both improve with strong enforcement.

- Secondary teachers and leaders are twice as likely (2.0 times) to say their students follow the rules consistently when rules are enforced to a great extent.

- Simply telling Year 12-13 students to put phones away halves (0.5 times) their compliance.

Discussion points for staff meetings

We found that sharing evidence of impact with teachers is an effective motivator to change their practice. Below is some key research that may be useful to share with staff:

Why is teacher support important?

- When secondary teachers support the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy to a ‘great extent’, schools are over twice as likely (2.2 times) to see improvements in students’ ability to focus on schoolwork, and one and a half times more likely (1.7 times) to report that student achievement has improved.

- Strong teacher enforcement is key to improving student outcomes. Student behaviour in the classroom and bullying both improve with strong enforcement.

- Secondary teachers and leaders are twice as likely (2.0 times) to say their students follow the rules consistently when rules are enforced to a great extent.

- Simply telling Year 12-13 students to put phones away halves (0.5 times) their compliance.

How do cell phones in classrooms impact learning?

- There is increasing evidence that simply having a phone nearby can reduce attention and performance in cognitive tasks. Studies have shown that just having a phone nearby can reduce ‘working memory’ capacity.

- Cell phone ownership among young people in New Zealand is high. Almost all (97 percent) 15-year-olds in New Zealand have their own phone.

- Distraction due to digital devices, such as cell phones, is a problem in classrooms around the world, but is a particular problem in New Zealand. The 2022 PISA results show New Zealand to be ranked fifth in the world for students being distracted by digital devices in maths classes.

- In New Zealand, this was notably higher, with almost a half (46 percent) of students distracted by digital devices during every or most of their maths lessons in 2022.

How do cell phones in classrooms impact learning?

- There is increasing evidence that simply having a phone nearby can reduce attention and performance in cognitive tasks. Studies have shown that just having a phone nearby can reduce ‘working memory’ capacity.

- Cell phone ownership among young people in New Zealand is high. Almost all (97 percent) 15-year-olds in New Zealand have their own phone.

- Distraction due to digital devices, such as cell phones, is a problem in classrooms around the world, but is a particular problem in New Zealand. The 2022 PISA results show New Zealand to be ranked fifth in the world for students being distracted by digital devices in maths classes.

- In New Zealand, this was notably higher, with almost a half (46 percent) of students distracted by digital devices during every or most of their maths lessons in 2022.

Managing the use of phones for learning purposes

When using cell phones for learning purposes, it is important that teachers take steps to manage them well so that students only have access to the phones for the duration of the specific learning task.

There is still an expectation that phones are away most of the time. Schools should still require students to use essential devices such as calculators, rather than rely on their phones. If recording work is an everyday activity, then schools should look to how they provide recording equipment so that students do not have to have their cell phones available every lesson.

“At times, we do allow students to use their phones in class for a specific task. The teacher must link it to the lesson learning objective and display a poster outside their classroom to signal to others who may be walking past that phones are being used in a controlled way.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL LEADER

“The students in my class will have to ask for the phone to be used and explain to me what they’re needing to do with it. They might be working on marketing… and so they’ll be accessing an Instagram page that they’ve created for a product. But again, that all has to be authorised beforehand.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHER

Managing the use of phones for learning purposes

When using cell phones for learning purposes, it is important that teachers take steps to manage them well so that students only have access to the phones for the duration of the specific learning task.

There is still an expectation that phones are away most of the time. Schools should still require students to use essential devices such as calculators, rather than rely on their phones. If recording work is an everyday activity, then schools should look to how they provide recording equipment so that students do not have to have their cell phones available every lesson.

“At times, we do allow students to use their phones in class for a specific task. The teacher must link it to the lesson learning objective and display a poster outside their classroom to signal to others who may be walking past that phones are being used in a controlled way.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL LEADER

“The students in my class will have to ask for the phone to be used and explain to me what they’re needing to do with it. They might be working on marketing… and so they’ll be accessing an Instagram page that they’ve created for a product. But again, that all has to be authorised beforehand.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHER

Managing exemptions

It is important that schools develop clear processes for managing exemptions for students who need to access their cell phones for medical or learning support needs – and to communicate these processes to teachers. Just over a quarter of staff reported that they did not know if their school allowed exemptions for health reasons (26 percent). Just under four in ten (38 percent) teachers did not know if their school allowed exemptions for students with disabilities or specific learning needs.

“I’ve seen teachers that fail to understand, even if the kids have been given the exemption… particularly for neurodiversity…”

- BOARD MEMBER

We heard that exemptions work best when students are given ‘exemption cards’ that they can produce as evidence of their exemption. This means that teachers are not required to remember who has exemptions, or to log on somewhere during a lesson or during duty to check. Relieving teachers also find it easier to manage exemptions when students carry exemption cards with them. Ensuring that staff are aware of the exemption policy is critical for these students.

“We have around about 90 students on our exemption list. Because that list is so large, it’s really difficult for teachers to track who has the exemption and who doesn’t. So, you might get to know that if it’s a regular class. But if there’s a reliever in there, or if the kids are moving between one venue and another on a large campus and a teacher walks past, it’s difficult.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL LEADER

Managing exemptions

It is important that schools develop clear processes for managing exemptions for students who need to access their cell phones for medical or learning support needs – and to communicate these processes to teachers. Just over a quarter of staff reported that they did not know if their school allowed exemptions for health reasons (26 percent). Just under four in ten (38 percent) teachers did not know if their school allowed exemptions for students with disabilities or specific learning needs.

“I’ve seen teachers that fail to understand, even if the kids have been given the exemption… particularly for neurodiversity…”

- BOARD MEMBER

We heard that exemptions work best when students are given ‘exemption cards’ that they can produce as evidence of their exemption. This means that teachers are not required to remember who has exemptions, or to log on somewhere during a lesson or during duty to check. Relieving teachers also find it easier to manage exemptions when students carry exemption cards with them. Ensuring that staff are aware of the exemption policy is critical for these students.

“We have around about 90 students on our exemption list. Because that list is so large, it’s really difficult for teachers to track who has the exemption and who doesn’t. So, you might get to know that if it’s a regular class. But if there’s a reliever in there, or if the kids are moving between one venue and another on a large campus and a teacher walks past, it’s difficult.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL LEADER

3 - Get students on board

Students are more likely to support the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy when they understand the evidence and reasons behind the rules. Creating an environment where the rules are understood and easy to follow leads to successful implementation of the policy.

Why does getting students on board matter? There is better compliance when students understand the reasons and evidence behind the cell phone rules. Students benefit when teachers take practical steps to support them to easily follow the rules, and spend time making sure students have a clear understanding of the reasons behind the rules and how the rule benefits them. Students who see the rules as fair and reasonable report higher positive outcomes than students who perceive the rules as unfair.

DID YOU KNOW?

Three in ten students (30 percent) who break the rules do so because they don’t agree with them, or think the rules are unfair.

How can you get students on board?

School leaders can do this by:

1) helping students understand how ‘Phones Away for the Day’ benefits them

2) finding practical ways to make following the rules easy.

Students are more likely to support the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy when they understand the evidence and reasons behind the rules. Creating an environment where the rules are understood and easy to follow leads to successful implementation of the policy.

Why does getting students on board matter? There is better compliance when students understand the reasons and evidence behind the cell phone rules. Students benefit when teachers take practical steps to support them to easily follow the rules, and spend time making sure students have a clear understanding of the reasons behind the rules and how the rule benefits them. Students who see the rules as fair and reasonable report higher positive outcomes than students who perceive the rules as unfair.

DID YOU KNOW?

Three in ten students (30 percent) who break the rules do so because they don’t agree with them, or think the rules are unfair.

How can you get students on board?

School leaders can do this by:

1) helping students understand how ‘Phones Away for the Day’ benefits them

2) finding practical ways to make following the rules easy.

1) Helping students to understand how ‘Phones Away for the Day’ benefits them

There is an increasing evidence base showing that the presence of cell phones leads to distraction in the classroom and impacts working memory, which is critical for learning. Data also shows that social media use, usually accessed via phones, has negative impacts on student wellbeing. Sharing data like this with students can help them understand why the rule is in place: that it’s not an arbitrary rule, it’s about their learning and wellbeing. Even though the policy is now mandatory, it’s still important to reinforce the purpose behind it. Students are less likely to perceive the rule as unfair when they understand the evidence.

Schools can build and maintain student buy-in by revisiting the ‘why?’ and embedding the policy into school culture through assemblies and classroom discussions. Helping students understand how responsible phone use can support their learning can then be used to sustain momentum, ensure consistent application, and strengthen long-term support.

“The value of a secondary school education is not effectively communicated to this generation of students. To them, the consequence of breaking the rule is getting their phone confiscated, not how it impacts their education or wellbeing.”

- PARENT/WHĀNAU OF SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENT

DID YOU KNOW?

Around eight in ten leaders (85 percent) and teachers (79 percent) say that students understanding the purpose of the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy helps them to implement the rules. We found in secondary schools when students understood the purpose of the rules to a great extent, leaders and teachers were one and a half times more likely (1.6 times) to report a high level of compliance.

1) Helping students to understand how ‘Phones Away for the Day’ benefits them

There is an increasing evidence base showing that the presence of cell phones leads to distraction in the classroom and impacts working memory, which is critical for learning. Data also shows that social media use, usually accessed via phones, has negative impacts on student wellbeing. Sharing data like this with students can help them understand why the rule is in place: that it’s not an arbitrary rule, it’s about their learning and wellbeing. Even though the policy is now mandatory, it’s still important to reinforce the purpose behind it. Students are less likely to perceive the rule as unfair when they understand the evidence.

Schools can build and maintain student buy-in by revisiting the ‘why?’ and embedding the policy into school culture through assemblies and classroom discussions. Helping students understand how responsible phone use can support their learning can then be used to sustain momentum, ensure consistent application, and strengthen long-term support.

“The value of a secondary school education is not effectively communicated to this generation of students. To them, the consequence of breaking the rule is getting their phone confiscated, not how it impacts their education or wellbeing.”

- PARENT/WHĀNAU OF SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENT

DID YOU KNOW?

Around eight in ten leaders (85 percent) and teachers (79 percent) say that students understanding the purpose of the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy helps them to implement the rules. We found in secondary schools when students understood the purpose of the rules to a great extent, leaders and teachers were one and a half times more likely (1.6 times) to report a high level of compliance.

2) Finding practical ways to make following the rules easy

There are steps school leaders can take to make following the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy easier for students. This starts with thinking about the reasons students might be tempted to break the rule (for example wanting to check digital timetables, be in contact with parents and whānau, or feeling socially disconnected or bored during break times) and considering practical ways to mitigate those reasons. Addressing key issues for students, such as having channels of alternative communication in place between them and home and providing phone-free activities for them during school breaks, makes it easier to comply with the cell phone rules.

DID YOU KNOW?

Just under six in ten secondary students (59 percent), and just under four in ten primary students (39 percent), break the rules to stay connected with the family.

2) Finding practical ways to make following the rules easy

There are steps school leaders can take to make following the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy easier for students. This starts with thinking about the reasons students might be tempted to break the rule (for example wanting to check digital timetables, be in contact with parents and whānau, or feeling socially disconnected or bored during break times) and considering practical ways to mitigate those reasons. Addressing key issues for students, such as having channels of alternative communication in place between them and home and providing phone-free activities for them during school breaks, makes it easier to comply with the cell phone rules.

DID YOU KNOW?

Just under six in ten secondary students (59 percent), and just under four in ten primary students (39 percent), break the rules to stay connected with the family.

Real-life example: Engaging students in cell phone expectations

One large urban full primary school began the year by asking students to reflect on the purpose of learning devices and asking students what ‘reasonable use’ looked like. Students contributed to setting the parameters of use and had a say in the wording of the policy. This helped set the tone for the year and reinforced the idea that the policy was about supporting learning, not just enforcing rules.

Real-life example: Encouraging breaktime activities to help students stay engaged

Some schools found that offering structured activities during break times helps reduce phone use, by keeping students engaged and socially connected. Leaders told us that this approach was especially effective in areas of the school that were less supervised or where students were more likely to disengage.

One urban secondary school invested in a range of equipment for use at lunchtimes. This included table tennis tables, volleyball equipment, and basketball hoops. Their teacher in charge of house activities organised lunchtime house competitions to get students engaged. They also made music equipment available and have Lego sets that can be issued from the library. Duty teachers report a significant reduction in lunchtime device use.

“Leadership have really led from the get-go… In breaks, lunch, in those danger periods I guess, for taking your phone out, they strategically organised sport and activities and clubs and really got behind it… That was led by leadership and pretty organised stuff.”

- EDUCATIONAL LEADER

Students also recognise the value of having more to do during breaks. Several note that boredom was a key reason they reached for their phones, and that having fun, inclusive activities helps make the rule easier to follow.

“Fun activities because lots of students use their phone because of boredom.”

- STUDENT

“Allowing safe spaces for kids who struggle with not having friends to go or activities for them to do that you don’t need a group of people for, [like] not board games.”

- STUDENT

By creating engaging, inclusive breaktime options, schools help students stay connected and active – making it easier to follow the rules and reducing the temptation to use phones during the school day.

Real-life example: Providing practical solutions to remove reliance on cell phones

In response to student feedback, some schools also made practical changes to reduce reliance on phones for everyday tasks. For example, instead of asking students to take photos of their timetables or check them on their phones, schools returned to printing and distributing paper copies.

“Sometimes I need to use my phone to check my timetable between classes.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENT

Some schools have spare calculators and computers available for students who don’t own these devices or who forget them. This prevents these students needing to access their phones.

We heard that these small but intentional shifts help reduce the need for students to use their phones during the day, while reinforcing the message that learning (and not screen time) is the priority while they are at school.

Real-life example: Engaging students in cell phone expectations

One large urban full primary school began the year by asking students to reflect on the purpose of learning devices and asking students what ‘reasonable use’ looked like. Students contributed to setting the parameters of use and had a say in the wording of the policy. This helped set the tone for the year and reinforced the idea that the policy was about supporting learning, not just enforcing rules.

Real-life example: Encouraging breaktime activities to help students stay engaged

Some schools found that offering structured activities during break times helps reduce phone use, by keeping students engaged and socially connected. Leaders told us that this approach was especially effective in areas of the school that were less supervised or where students were more likely to disengage.

One urban secondary school invested in a range of equipment for use at lunchtimes. This included table tennis tables, volleyball equipment, and basketball hoops. Their teacher in charge of house activities organised lunchtime house competitions to get students engaged. They also made music equipment available and have Lego sets that can be issued from the library. Duty teachers report a significant reduction in lunchtime device use.

“Leadership have really led from the get-go… In breaks, lunch, in those danger periods I guess, for taking your phone out, they strategically organised sport and activities and clubs and really got behind it… That was led by leadership and pretty organised stuff.”

- EDUCATIONAL LEADER

Students also recognise the value of having more to do during breaks. Several note that boredom was a key reason they reached for their phones, and that having fun, inclusive activities helps make the rule easier to follow.

“Fun activities because lots of students use their phone because of boredom.”

- STUDENT

“Allowing safe spaces for kids who struggle with not having friends to go or activities for them to do that you don’t need a group of people for, [like] not board games.”

- STUDENT

By creating engaging, inclusive breaktime options, schools help students stay connected and active – making it easier to follow the rules and reducing the temptation to use phones during the school day.

Real-life example: Providing practical solutions to remove reliance on cell phones

In response to student feedback, some schools also made practical changes to reduce reliance on phones for everyday tasks. For example, instead of asking students to take photos of their timetables or check them on their phones, schools returned to printing and distributing paper copies.

“Sometimes I need to use my phone to check my timetable between classes.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENT

Some schools have spare calculators and computers available for students who don’t own these devices or who forget them. This prevents these students needing to access their phones.

We heard that these small but intentional shifts help reduce the need for students to use their phones during the day, while reinforcing the message that learning (and not screen time) is the priority while they are at school.

Reflective questions:

- How well have we communicated the reasons and evidence behind the cell phone rules to our students? Do they understand the benefits?

- How are we embedding the policy into our everyday school culture? Are we regularly revisiting the ‘why’ with students to maintain buy-in and momentum?

- Are we responding to the key reasons our students would be tempted to break the rules? What practical steps have we taken to make it easy for students to follow the policy? Are there further actions we could take?

Reflective questions:

- How well have we communicated the reasons and evidence behind the cell phone rules to our students? Do they understand the benefits?

- How are we embedding the policy into our everyday school culture? Are we regularly revisiting the ‘why’ with students to maintain buy-in and momentum?

- Are we responding to the key reasons our students would be tempted to break the rules? What practical steps have we taken to make it easy for students to follow the policy? Are there further actions we could take?

4 - Get parents and whānau on board

Successful implementation of ‘Phones Away for the Day’ relies on parent and whānau buy-in and support. Parents and whānau are more supportive when they understand the reasons behind the policy and have clear alternative communication channels.

Why does getting parents and whānau on board matter?

Support from parents and whānau is essential for getting ‘Phones Away for the Day’ implemented. When parents and whānau are intentional about not undermining the cell phone rules, and actively support the school policy, students are more likely to comply. In our review, we found that parents and whānau sometimes undermine the policy by contacting their children during class time.

How can you get parents and whānau on board?

School leaders can do this by:

1) communicating the purpose and benefits of the rules to parents and whānau

2) providing alternative ways for parents and whānau to communicate with their children.

Successful implementation of ‘Phones Away for the Day’ relies on parent and whānau buy-in and support. Parents and whānau are more supportive when they understand the reasons behind the policy and have clear alternative communication channels.

Why does getting parents and whānau on board matter?

Support from parents and whānau is essential for getting ‘Phones Away for the Day’ implemented. When parents and whānau are intentional about not undermining the cell phone rules, and actively support the school policy, students are more likely to comply. In our review, we found that parents and whānau sometimes undermine the policy by contacting their children during class time.

How can you get parents and whānau on board?

School leaders can do this by:

1) communicating the purpose and benefits of the rules to parents and whānau

2) providing alternative ways for parents and whānau to communicate with their children.

1) Communicating the purpose and benefits of the rules to parents and whānau

We found that parents and whānau contacting students directly during the school day was a common barrier, particularly in schools where students keep their phones with them. Teachers noted that this undermines enforcement and creates confusion. For parents and whānau to support the cell phone rules, they need to understand the impact that cell phones have on learning and wellbeing outcomes for their children. It can be useful to take the time to frame the policy with parents and whānau in terms of how it benefits students. This prevents parents and whānau from seeing the rule as punitive.

“Some parents are enablers… For them it’s not important ‘I need to contact my kid at any time’ – well, no you don’t – there’s an office phone here at school like there was in our time… Some parents were the early users of cell phones and are equally addicted as their kids are.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL LEADER

“So, I think letting parents know that they are part of the solution as well as part of the problem, is probably the way to go.”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL LEADER

DID YOU KNOW?

Just under nine in ten school leaders (89 percent) find parent and whānau support helpful in implementing the cell phone rules.

DID YOU KNOW?

Just under three in ten (29 percent) parents and whānau agree that “the phone ban has made me feel concerned about not being able to contact my child during the school day.”

1) Communicating the purpose and benefits of the rules to parents and whānau

We found that parents and whānau contacting students directly during the school day was a common barrier, particularly in schools where students keep their phones with them. Teachers noted that this undermines enforcement and creates confusion. For parents and whānau to support the cell phone rules, they need to understand the impact that cell phones have on learning and wellbeing outcomes for their children. It can be useful to take the time to frame the policy with parents and whānau in terms of how it benefits students. This prevents parents and whānau from seeing the rule as punitive.

“Some parents are enablers… For them it’s not important ‘I need to contact my kid at any time’ – well, no you don’t – there’s an office phone here at school like there was in our time… Some parents were the early users of cell phones and are equally addicted as their kids are.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL LEADER

“So, I think letting parents know that they are part of the solution as well as part of the problem, is probably the way to go.”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL LEADER

DID YOU KNOW?

Just under nine in ten school leaders (89 percent) find parent and whānau support helpful in implementing the cell phone rules.

DID YOU KNOW?

Just under three in ten (29 percent) parents and whānau agree that “the phone ban has made me feel concerned about not being able to contact my child during the school day.”

2) Providing alternative ways for parents and whānau to communicate with their children

We heard that the biggest barrier for parents and whānau to following the cell phone rules is concern around not being able to get in contact with their child. Although many parents and whānau support the policy’s intent, they have not developed alternative communication systems that would make it easy to stay compliant with the cell phone rules.

We heard that it’s important for parents and whānau to have confidence and peace of mind that they can get important information to their children when they need to. Developing an effective channel of communication for parents and whānau, and ensuring they are fully aware of how it works, is vital for effective implementation of the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy.

“We live out of the city and travel arrangements change frequently and need to be communicated. I email her, but she doesn’t always get her emails if she’s not on her laptop.”

- PARENT/WHĀNAU

DID YOU KNOW?

Six in ten (60 percent) parents and whānau with secondary-aged children who break the rules say it’s because their child wants to stay connected with them or other family.

2) Providing alternative ways for parents and whānau to communicate with their children

We heard that the biggest barrier for parents and whānau to following the cell phone rules is concern around not being able to get in contact with their child. Although many parents and whānau support the policy’s intent, they have not developed alternative communication systems that would make it easy to stay compliant with the cell phone rules.

We heard that it’s important for parents and whānau to have confidence and peace of mind that they can get important information to their children when they need to. Developing an effective channel of communication for parents and whānau, and ensuring they are fully aware of how it works, is vital for effective implementation of the ‘Phones Away for the Day’ policy.

“We live out of the city and travel arrangements change frequently and need to be communicated. I email her, but she doesn’t always get her emails if she’s not on her laptop.”

- PARENT/WHĀNAU

DID YOU KNOW?

Six in ten (60 percent) parents and whānau with secondary-aged children who break the rules say it’s because their child wants to stay connected with them or other family.

Real-life example: Using experts to help parents and whānau understand why the rules are important

Some schools take proactive steps to help parents and whānau understand the reasons behind restricting phone use during school hours. Leaders told us that framing parents and whānau as part of the solution can help build shared responsibility and support for the policy.

Messages about cell phone use can be brought into wider discussions around cyber safety and social media. A primary school leader reflected on their school’s efforts to support cyber safety, including hosting several sessions with external facilitators. These sessions encouraged parents and whānau to reflect on their own decisions around phone use and helped them better understand the school’s approach.

“It’s parents who buy them [cell phones]. We’ve run a number of cyber safety meetings this year. We’ve had [a facilitator] come up and do this work with our people – very impactful, hard hitting to parents in terms of, ‘Why are you giving them phones?’ I’ve had a lot of good feedback from parents about it. I think what it has done is it’s… been helpful because they then can understand why we say the phones are not available during school hours. They understand that we have our own system, which we can monitor, and that we have no way of monitoring what parents are putting into their hands.”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL LEADER

Parents and whānau not on board?

To support schools to get parents and whānau on board, ERO has prepared a two-pager that shares key benefits of removing cell phones, and what they can do to help - including not messaging their children during class. Download a copy here: parent and whānau insights

Real-life example: Developing effective channels of communication with parents and whānau

We heard from many leaders that having a clear, reliable system in place helps reduce the need for direct phone contact and gives parents and whānau confidence that their messages will be passed on. These could be around things like school pick-ups or after school commitments.

One school strengthened its communication channels by making the school office the central point of contact. Staff record and relay messages to students promptly, and parents and whānau are reassured that this process works. The school also increased its use of digital channels for information-sharing with parents and whānau, such as Facebook and the school app, to keep parents and whānau informed about schedules, changes, and reminders.

Teachers note that students can still contact parents and whānau through their laptops if needed. But their emphasis is on reducing unnecessary interruptions and reinforcing the purpose of the policy.

“If it’s urgent, I contact the student centre who relays the information.”

- PARENT/WHĀNAU

“There is a system whereby parents ring the school, and messages get sent to the child.”

- PARENT/WHĀNAU

Real-life example: Using experts to help parents and whānau understand why the rules are important

Some schools take proactive steps to help parents and whānau understand the reasons behind restricting phone use during school hours. Leaders told us that framing parents and whānau as part of the solution can help build shared responsibility and support for the policy.

Messages about cell phone use can be brought into wider discussions around cyber safety and social media. A primary school leader reflected on their school’s efforts to support cyber safety, including hosting several sessions with external facilitators. These sessions encouraged parents and whānau to reflect on their own decisions around phone use and helped them better understand the school’s approach.

“It’s parents who buy them [cell phones]. We’ve run a number of cyber safety meetings this year. We’ve had [a facilitator] come up and do this work with our people – very impactful, hard hitting to parents in terms of, ‘Why are you giving them phones?’ I’ve had a lot of good feedback from parents about it. I think what it has done is it’s… been helpful because they then can understand why we say the phones are not available during school hours. They understand that we have our own system, which we can monitor, and that we have no way of monitoring what parents are putting into their hands.”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL LEADER

Parents and whānau not on board?

To support schools to get parents and whānau on board, ERO has prepared a two-pager that shares key benefits of removing cell phones, and what they can do to help - including not messaging their children during class. Download a copy here: parent and whānau insights

Real-life example: Developing effective channels of communication with parents and whānau

We heard from many leaders that having a clear, reliable system in place helps reduce the need for direct phone contact and gives parents and whānau confidence that their messages will be passed on. These could be around things like school pick-ups or after school commitments.

One school strengthened its communication channels by making the school office the central point of contact. Staff record and relay messages to students promptly, and parents and whānau are reassured that this process works. The school also increased its use of digital channels for information-sharing with parents and whānau, such as Facebook and the school app, to keep parents and whānau informed about schedules, changes, and reminders.

Teachers note that students can still contact parents and whānau through their laptops if needed. But their emphasis is on reducing unnecessary interruptions and reinforcing the purpose of the policy.

“If it’s urgent, I contact the student centre who relays the information.”

- PARENT/WHĀNAU

“There is a system whereby parents ring the school, and messages get sent to the child.”

- PARENT/WHĀNAU

Reflective questions:

- How clearly and consistently have we communicated the purpose and benefits of the cell phone rules to parents and whānau?

- How are we addressing common concerns from parents and whānau that may unintentionally undermine the policy?

- Are we actively engaging parents and whānau as partners in supporting the cell phone policy, rather than just informing them of the rules?

- What steps have we taken to build parent and whānau confidence in our communication systems and policy implementation? Do we know if they have concerns about our processes?

Reflective questions:

- How clearly and consistently have we communicated the purpose and benefits of the cell phone rules to parents and whānau?

- How are we addressing common concerns from parents and whānau that may unintentionally undermine the policy?

- Are we actively engaging parents and whānau as partners in supporting the cell phone policy, rather than just informing them of the rules?

- What steps have we taken to build parent and whānau confidence in our communication systems and policy implementation? Do we know if they have concerns about our processes?

Case study: A school-wide reset of cell phone expectations

A large secondary school of 2000 students in a diverse urban setting

Faced with widespread cell phone use across all areas of the school, staff at this school were highly motivated to change the culture of phone use. The senior leadership team introduced a cell phone policy and ways of working that ensured a cohesive and sustained approach to implementing change. Their approach demonstrates how it is possible to embed a new set of expectations around cell phone use. A combination of clearly defined rules, consistent enforcement, practical solutions, and monitoring systems has seen a dramatic shift in cell phone use.

Keeping rules consistent across all times and places