Related insights

Explore related documents that you might be interested in.

Read Online

Executive summary

Students’ mental health is strongly linked to their engagement, achievement, and school attendance. Counselling in Schools is an initiative which began in 2021 with the aim of providing evidence-based counselling support in primary, intermediate, and small secondary schools, to help young people thrive at school.

The Education Review Office looked at the effectiveness of Counselling in Schools, how well it reached the students it is targeted at, the impact it had, and some lessons for counselling programmes in the future. We found that counselling improves students’ mental health, and we also saw some encouraging signs of improved learning and wellbeing more widely.

What is Counselling in Schools?

The Counselling in Schools - Awhi Mai Awhi Atu programme (Counselling in Schools) was rolled out in primary, intermediate, and some small secondary schools. It’s available in selected schools in many regions, with a particular focus on schools with the greatest need.

Counselling in Schools involves working with community providers to develop a counselling approach that meets the needs of each school. Counselling within the programme involves a mix of individual, parent and whānau, group, and whole school sessions. The aim is to improve mental health for children and young people with mild to moderate needs, in an accessible setting – and for students who need a higher level of support, referrals are made to other services.

The Education Review Office (ERO) wanted to understand how effective Counselling in Schools has been. We evaluated it over three years. We were especially interested in:

- how well it reached the students it is targeted at

- the impact it had on students

- lessons we can learn for implementing counselling programmes in the future.

Key findings

Finding 1: Mental health needs for children and young people are rising, and it is impacting on their learning outcomes.

Worryingly, emotional distress among children is increasing. For children aged 14 or younger, it is estimated to have increased from 9 percent in 2016/17 to 13 percent in 2022/23. The ongoing impacts of Covid-19 are a likely driver.

As well as being concerning for children’s wellbeing, this also matters for their school achievement. Increased emotional distress and mental health needs have been found to significantly impact learning outcomes.

How effective was the implementation of Counselling in Schools?

Finding 2: The Counselling in Schools programme has evolved to be a mix of models that delivers mental health and social support to students.

Counselling in Schools offers a variety of types of counselling for students who need support. These are made available on the school site.

- 77 percent of Counselling in Schools sessions are individual sessions.

- 14 percent are group sessions.

- 1 percent are whole school sessions.

In schools, most referrals are made by teachers. Three in 10 of the programme’s counsellors have a counselling accreditation, six in 10 have some other accreditation (e.g., as occupational therapists), and the rest have no accreditation. Nine out of 10 Counselling in Schools counsellors are supervised by a registered counsellor. We know from international evidence that accreditation matters. A large-scale analysis of 107 studies shows that being a licensed counselling professional does make a difference to the quality of counselling – although there were benefits noted from non-licensed counsellors too. In our study, we heard that it was important to match the type of counsellor to the specific needs of the school.

How well did the programme reach the target students?

Finding 3: The programme successfully reaches primary school students in low socioeconomic areas who are in psychological distress. It reaches some groups who do not typically access counselling, such as Māori students and boys, but reaches lower numbers of Asian, Pacific, and MELAA students.

Encouragingly, the programme is reaching the students who most need support. Eight out of 10 schools where students can access Counselling in Schools are in low socio-economic areas, reflecting the programme’s aim to reach schools with higher need.

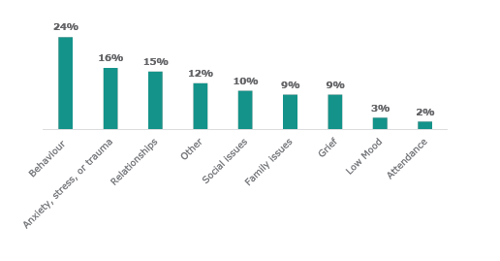

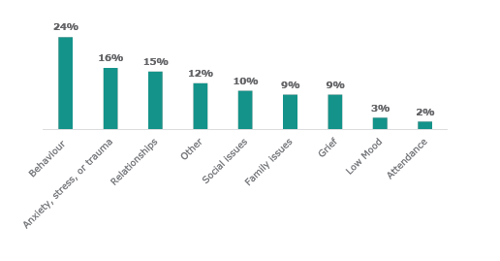

Individual students are referred to counselling for a range of reasons, including behaviour (24 percent), anxiety, stress, or trauma (16 percent), and relationships (15 percent). Seven in 10 (71 percent) students entering counselling are identified as being in distress, meaning that their pre-test mental health score represents the level of distress that is typical of those entering therapeutic services.

Māori students make up 60 percent of students receiving counselling. The proportion of Māori and NZ European/Pākehā students that access counselling is the same or higher than the school roll. But Pacific (8 percent), Asian (2 percent), and MELAA (1 percent) (Middle Eastern, Latin American, African) students are under-represented. This could mean that different approaches are needed to make sure that students of these ethnicities are being supported with mental health needs.

More boys access Counselling in Schools (55 percent) than girls (45 percent). This could be because school staff usually refer students for observable issues like behaviour (the most common referral reason), and boys are twice as likely to be referred for behaviour compared to girls.

Finding 4: The programme may not be reaching students who do not show signs of distress.

Three-quarters of referrals to counsellors are made by school staff, and one-quarter of students are referred due to their behaviour. Students are also referred for a wide range of other reasons, including grief and anxiety. ERO found that students with more hidden signs of distress are less likely to receive support, as it is harder for teachers to observe their distress.

What was the impact on students?

Finding 5: Counselling in Schools successfully reduces psychological distress for students, particularly for students who have more severe distress, and these improvements are sustained.

Encouragingly, eight in 10 students (80 percent) report improved psychological health after receiving counselling, and students with the most psychological distress have the largest improvement. Of the 71 percent of students who entered counselling reaching the clinical cutoff for distress, almost half no longer reach the cut-off for psychological distress at the end of counselling. This is a very positive outcome.

The greatest improvement is for students who experience the most severe distress before starting counselling. Ninety percent of those with the highest severity of mental health distress at the start improve.

This improvement lasts. Ninety-one percent of teachers and 98 percent of parents and whānau report students’ mental health improves following counselling. Four in five teachers (80 percent) report the improvements are still evident after six months, and three-quarters (74 percent) of parents and whānau say their child continues to show the improvements to mental health that they gained through counselling.

Finding 6: Counselling in Schools also shows signs of improving students’ attendance, engagement, and learning progress.

Nationally, learning progress is not consistently measured. In primary schools however, in our study, teachers report there are improvements in learning progress for over half of students who receive Counselling in Schools support. This was measured using the Learning Engagement Measurement Tool (LEMT), which is a rating-scale assessment designed by ERO to measure individual shifts in learning engagement. The tool looks at presence (attendance), participation (in learning and with others), and learning gains (achievement and progress). For more information about the LEMT, see our technical report: https://www.evidence.ero.govt.nz/documents/techinical-report-evaluation-of-counselling-in-schools. Eight out of 10 students, and nine out of 10 parents and whānau agreed that counselling improves students’ learning progress.

Teachers also report improvement in attendance for four in 10 students who attended counselling. Overall, seven out of 10 teachers (68 percent), eight out of 10 students (84 percent), and nine out of 10 parents and whānau agree that the Counselling in Schools programme improves students’ attendance (91 percent).

These improvements are sustained over time, reflecting sustained improvements to mental health. For example, six out of 10 parents and whānau (61 percent) say better attendance is sustained even after their child finishes counselling.

Finding 7: Students who entered counselling with the highest mental health needs are also most likely to see improvements in attendance and in their learning progress.

Students with the highest mental health scores had the biggest improvements to their attendance after counselling (61 percent), compared to 35 percent of other students with the lowest mental health scores. Mental health concerns are one of the biggest individual drivers of whether a student attends school regularly or not.

Students with the highest mental health needs are also more likely to see improvements in their learning. Two in three students (67 percent) with the highest mental health needs on the counselling pre-test saw improvements in learning progress from pre- to post-counselling, compared to 56 percent of students with the lowest mental health needs.

Finding 8: Teachers report that Counselling in Schools improves overall classroom behaviour.

Classroom behaviour is a major problem in Aotearoa New Zealand. Students, teachers, and parents and whānau all report that Counselling in Schools leads to improvements in students’ emotional regulation and behaviour. Three in four teachers (76 percent) also report improvements in wider classroom behaviour due to counselling.

Students told us they learn strategies to manage their emotions, such as ways to keep themselves calm, express their emotions effectively, and navigate relationships. Teachers also told us that the counsellors provide them with strategies and tools to use with students to improve their behaviour.

What have we learnt from the Counselling in Schools programme?

Our evaluation highlights some key lessons for programmes that support primary-aged students’ mental health.

Lesson 1: Investing in psychological support in primary schools can reduce distress and improve learning, attendance, and behaviour outcomes.

The findings of our evaluation show a range of strongly positive outcomes from the Counselling in Schools programme. Students who receive support show significant gains in their psychological health, and this has a lasting, positive impact. Those students with high levels of distress show the most improvement – meaning that the programme is having success in its aim to impact those students who need it most. It’s also encouraging that we saw improvements in students’ attendance, behaviour, and learning progress. Taken together, our findings support investment in mental health support in schools for young students.

Lesson 2: Counselling in primary schools works best when on the school site, and when students receive more than three hours of support.

Students, teachers, and parents and whānau, all report that having counsellors on-site means better access, particularly for those in remote areas, and improves the uptake of counselling.

It is also important to provide a significant amount of counselling. Students who receive at least three hours of counselling are more likely to show improved mental health, learning, and engagement outcomes.

Lesson 3: Having multiple referral pathways by teachers, students, and parents and whānau, is potentially important in order to capture students who do not exhibit obvious signs of distress.

Three in four (75 percent) students are referred to counselling by school staff. The next most common referral pathways are through parents and whānau (14 percent) and self-referrals (4 percent). We heard that teachers are more likely to pick up observable issues such as behaviour, leading to the high referral rates for behaviour (24 percent of all referrals), than less observable issues such as grief.

A range of ways that students can be referred for counselling is important to help ensure that less observable issues are picked up. This relies on strong relationships between the school and students or parents and whānau, so that they have the information they need to self-refer or refer their children.

Lesson 4: The programme is promising but we need to understand more about which elements are key to success to be sure it can be effectively replicated in a wider range of schools.

Counselling in Schools is a promising programme. Positive impacts on mental health are equal to, or better than, other national and international school-based counselling programmes.

However, Counselling in Schools is currently delivered in different ways. ERO recommends there to be more development of the programme specifications to understand both value for money, and what elements are key to success, and therefore essential in order to replicate its success in a larger variety of schools.

Students’ mental health is strongly linked to their engagement, achievement, and school attendance. Counselling in Schools is an initiative which began in 2021 with the aim of providing evidence-based counselling support in primary, intermediate, and small secondary schools, to help young people thrive at school.

The Education Review Office looked at the effectiveness of Counselling in Schools, how well it reached the students it is targeted at, the impact it had, and some lessons for counselling programmes in the future. We found that counselling improves students’ mental health, and we also saw some encouraging signs of improved learning and wellbeing more widely.

What is Counselling in Schools?

The Counselling in Schools - Awhi Mai Awhi Atu programme (Counselling in Schools) was rolled out in primary, intermediate, and some small secondary schools. It’s available in selected schools in many regions, with a particular focus on schools with the greatest need.

Counselling in Schools involves working with community providers to develop a counselling approach that meets the needs of each school. Counselling within the programme involves a mix of individual, parent and whānau, group, and whole school sessions. The aim is to improve mental health for children and young people with mild to moderate needs, in an accessible setting – and for students who need a higher level of support, referrals are made to other services.

The Education Review Office (ERO) wanted to understand how effective Counselling in Schools has been. We evaluated it over three years. We were especially interested in:

- how well it reached the students it is targeted at

- the impact it had on students

- lessons we can learn for implementing counselling programmes in the future.

Key findings

Finding 1: Mental health needs for children and young people are rising, and it is impacting on their learning outcomes.

Worryingly, emotional distress among children is increasing. For children aged 14 or younger, it is estimated to have increased from 9 percent in 2016/17 to 13 percent in 2022/23. The ongoing impacts of Covid-19 are a likely driver.

As well as being concerning for children’s wellbeing, this also matters for their school achievement. Increased emotional distress and mental health needs have been found to significantly impact learning outcomes.

How effective was the implementation of Counselling in Schools?

Finding 2: The Counselling in Schools programme has evolved to be a mix of models that delivers mental health and social support to students.

Counselling in Schools offers a variety of types of counselling for students who need support. These are made available on the school site.

- 77 percent of Counselling in Schools sessions are individual sessions.

- 14 percent are group sessions.

- 1 percent are whole school sessions.

In schools, most referrals are made by teachers. Three in 10 of the programme’s counsellors have a counselling accreditation, six in 10 have some other accreditation (e.g., as occupational therapists), and the rest have no accreditation. Nine out of 10 Counselling in Schools counsellors are supervised by a registered counsellor. We know from international evidence that accreditation matters. A large-scale analysis of 107 studies shows that being a licensed counselling professional does make a difference to the quality of counselling – although there were benefits noted from non-licensed counsellors too. In our study, we heard that it was important to match the type of counsellor to the specific needs of the school.

How well did the programme reach the target students?

Finding 3: The programme successfully reaches primary school students in low socioeconomic areas who are in psychological distress. It reaches some groups who do not typically access counselling, such as Māori students and boys, but reaches lower numbers of Asian, Pacific, and MELAA students.

Encouragingly, the programme is reaching the students who most need support. Eight out of 10 schools where students can access Counselling in Schools are in low socio-economic areas, reflecting the programme’s aim to reach schools with higher need.

Individual students are referred to counselling for a range of reasons, including behaviour (24 percent), anxiety, stress, or trauma (16 percent), and relationships (15 percent). Seven in 10 (71 percent) students entering counselling are identified as being in distress, meaning that their pre-test mental health score represents the level of distress that is typical of those entering therapeutic services.

Māori students make up 60 percent of students receiving counselling. The proportion of Māori and NZ European/Pākehā students that access counselling is the same or higher than the school roll. But Pacific (8 percent), Asian (2 percent), and MELAA (1 percent) (Middle Eastern, Latin American, African) students are under-represented. This could mean that different approaches are needed to make sure that students of these ethnicities are being supported with mental health needs.

More boys access Counselling in Schools (55 percent) than girls (45 percent). This could be because school staff usually refer students for observable issues like behaviour (the most common referral reason), and boys are twice as likely to be referred for behaviour compared to girls.

Finding 4: The programme may not be reaching students who do not show signs of distress.

Three-quarters of referrals to counsellors are made by school staff, and one-quarter of students are referred due to their behaviour. Students are also referred for a wide range of other reasons, including grief and anxiety. ERO found that students with more hidden signs of distress are less likely to receive support, as it is harder for teachers to observe their distress.

What was the impact on students?

Finding 5: Counselling in Schools successfully reduces psychological distress for students, particularly for students who have more severe distress, and these improvements are sustained.

Encouragingly, eight in 10 students (80 percent) report improved psychological health after receiving counselling, and students with the most psychological distress have the largest improvement. Of the 71 percent of students who entered counselling reaching the clinical cutoff for distress, almost half no longer reach the cut-off for psychological distress at the end of counselling. This is a very positive outcome.

The greatest improvement is for students who experience the most severe distress before starting counselling. Ninety percent of those with the highest severity of mental health distress at the start improve.

This improvement lasts. Ninety-one percent of teachers and 98 percent of parents and whānau report students’ mental health improves following counselling. Four in five teachers (80 percent) report the improvements are still evident after six months, and three-quarters (74 percent) of parents and whānau say their child continues to show the improvements to mental health that they gained through counselling.

Finding 6: Counselling in Schools also shows signs of improving students’ attendance, engagement, and learning progress.

Nationally, learning progress is not consistently measured. In primary schools however, in our study, teachers report there are improvements in learning progress for over half of students who receive Counselling in Schools support. This was measured using the Learning Engagement Measurement Tool (LEMT), which is a rating-scale assessment designed by ERO to measure individual shifts in learning engagement. The tool looks at presence (attendance), participation (in learning and with others), and learning gains (achievement and progress). For more information about the LEMT, see our technical report: https://www.evidence.ero.govt.nz/documents/techinical-report-evaluation-of-counselling-in-schools. Eight out of 10 students, and nine out of 10 parents and whānau agreed that counselling improves students’ learning progress.

Teachers also report improvement in attendance for four in 10 students who attended counselling. Overall, seven out of 10 teachers (68 percent), eight out of 10 students (84 percent), and nine out of 10 parents and whānau agree that the Counselling in Schools programme improves students’ attendance (91 percent).

These improvements are sustained over time, reflecting sustained improvements to mental health. For example, six out of 10 parents and whānau (61 percent) say better attendance is sustained even after their child finishes counselling.

Finding 7: Students who entered counselling with the highest mental health needs are also most likely to see improvements in attendance and in their learning progress.

Students with the highest mental health scores had the biggest improvements to their attendance after counselling (61 percent), compared to 35 percent of other students with the lowest mental health scores. Mental health concerns are one of the biggest individual drivers of whether a student attends school regularly or not.

Students with the highest mental health needs are also more likely to see improvements in their learning. Two in three students (67 percent) with the highest mental health needs on the counselling pre-test saw improvements in learning progress from pre- to post-counselling, compared to 56 percent of students with the lowest mental health needs.

Finding 8: Teachers report that Counselling in Schools improves overall classroom behaviour.

Classroom behaviour is a major problem in Aotearoa New Zealand. Students, teachers, and parents and whānau all report that Counselling in Schools leads to improvements in students’ emotional regulation and behaviour. Three in four teachers (76 percent) also report improvements in wider classroom behaviour due to counselling.

Students told us they learn strategies to manage their emotions, such as ways to keep themselves calm, express their emotions effectively, and navigate relationships. Teachers also told us that the counsellors provide them with strategies and tools to use with students to improve their behaviour.

What have we learnt from the Counselling in Schools programme?

Our evaluation highlights some key lessons for programmes that support primary-aged students’ mental health.

Lesson 1: Investing in psychological support in primary schools can reduce distress and improve learning, attendance, and behaviour outcomes.

The findings of our evaluation show a range of strongly positive outcomes from the Counselling in Schools programme. Students who receive support show significant gains in their psychological health, and this has a lasting, positive impact. Those students with high levels of distress show the most improvement – meaning that the programme is having success in its aim to impact those students who need it most. It’s also encouraging that we saw improvements in students’ attendance, behaviour, and learning progress. Taken together, our findings support investment in mental health support in schools for young students.

Lesson 2: Counselling in primary schools works best when on the school site, and when students receive more than three hours of support.

Students, teachers, and parents and whānau, all report that having counsellors on-site means better access, particularly for those in remote areas, and improves the uptake of counselling.

It is also important to provide a significant amount of counselling. Students who receive at least three hours of counselling are more likely to show improved mental health, learning, and engagement outcomes.

Lesson 3: Having multiple referral pathways by teachers, students, and parents and whānau, is potentially important in order to capture students who do not exhibit obvious signs of distress.

Three in four (75 percent) students are referred to counselling by school staff. The next most common referral pathways are through parents and whānau (14 percent) and self-referrals (4 percent). We heard that teachers are more likely to pick up observable issues such as behaviour, leading to the high referral rates for behaviour (24 percent of all referrals), than less observable issues such as grief.

A range of ways that students can be referred for counselling is important to help ensure that less observable issues are picked up. This relies on strong relationships between the school and students or parents and whānau, so that they have the information they need to self-refer or refer their children.

Lesson 4: The programme is promising but we need to understand more about which elements are key to success to be sure it can be effectively replicated in a wider range of schools.

Counselling in Schools is a promising programme. Positive impacts on mental health are equal to, or better than, other national and international school-based counselling programmes.

However, Counselling in Schools is currently delivered in different ways. ERO recommends there to be more development of the programme specifications to understand both value for money, and what elements are key to success, and therefore essential in order to replicate its success in a larger variety of schools.

About this report

Student mental health is strongly linked to engagement, achievement, and school attendance. Counselling in Schools - Awhi Mai, Awhi Atu is an initiative which began in 2021 with the aim of providing evidence-based counselling support. The programme was designed to enable flexibility in providing different approaches for counselling in primary and intermediate schools

This report looks at the Counselling in Schools initiative, including access to the programme, the mental health and learning and engagement outcomes for students, and the lessons learnt for implementation.

Mental health needs for children and young people are rising, and it is impacting on their learning outcomes.

Mental health for young people is getting worse. The most recent New Zealand health survey showed that significant emotional problems among 3 to 14-year-olds are increasing, from 9 percent in 2016/17 to 13 percent or 111,000 children in 2022/23. The ongoing impacts of Covid-19 are a likely driver.

Poor mental health in children impacts their educational outcomes. Good mental health is needed to enable learning and educational progress. It helps with paying attention in class and managing challenges at school. Poorer mental health effects attendance and engagement and it can lead to lower educational attainment and leaving school earlier.

The Education Review Office’s (ERO) report ‘Missing out’ on school attendance found that 46 percent of parents were likely to keep their children out of school if they have mental health challenges.

Counselling in Schools

Counselling in Schools was introduced to improve mental health outcomes for students at primary, intermediate and in some small secondary schools. It was established to improve mental health for children and young people, with mild to moderate needs, in an accessible setting on school grounds.

Counselling in Schools is available in most regions, with a particular focus on schools with the greatest need. Those schools then work with community providers to develop a counselling approach that works for their school environment and based on the needs of the school. ‘Counselling’ is used broadly, with a mixture of individual, family, group and whole-school sessions. For students who need a higher level of support, referrals are made to other services.

Why we looked at Counselling in Schools

ERO is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early learning services, schools, and kura. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports schools to provide quality education for Aotearoa New Zealand’s students.

ERO’s report on the impact of Covid-19 identified an increasing impact on student mental health, which then impacted on their education. It is important to understand how to effectively support these students, so ERO has evaluated Counselling in Schools to build the evidence base.

This report describes what we found about Counselling in Schools initiative over its three years of operation. We highlight the experiences of students who access counselling through the initiative, counsellors and providers involved, teachers and school staff who refer and have students accessing the initiative, and the parents and whānau of students receiving counselling.

This report is accompanied by a detailed technical report that provides more information on what we found, the data we draw on and how we conducted our evaluation.

What we looked at

ERO has conducted a three-phase evaluation over three years (Term 4 2021-Term 2 2024), and all three phases have informed this report. Phase One gave an early update on access to the initiative and implementation lessons. Phase Two provided another update on access and implementation of the initiative and early findings into the impacts on students’ mental health and learning and engagement. In Phase Three we looked at three key questions:

- What was the impact of the initiative on students’ wellbeing/hauora; students’ engagement and learning; and classroom behaviour?

- To what extent did the initiative increase access to counselling for primary school students? For whom? Was access equitable?

- What are some lessons learnt about implementation of this initiative?

The earlier reports can be found here:

- Phase 1 findings https://ero.govt.nz/sites/default/files/media-documents/2022-07/CiS%20summary%20of%20findings%20for%20proactive%20release.PDF

- Phase 2 findings https://ero.govt.nz/sites/default/files/media-documents/2023-06/Summary%20of%20Findings%20-%20slides.pdf

Where we looked

This report looks at the Counselling in Schools initiative within primary and intermediate schools (while the programme does operate in a small number of secondary schools, we excluded this data from our evaluation).

In this report, we use the term counsellors to refer to the practitioners who are contracted by community-based providers to schools as part of the Counselling in Schools initiative. Counselling practitioners include both practitioners who are registered with a professional body, and those who are not registered but working under the supervision of a registered counselling practitioner.

How we gathered this information

Across each phase of the evaluation, we gathered information through:

|

Phase 1 |

Phase 2 |

Phase 3 |

|

Administrative data Surveys of:

Interviews and focus groups with:

Document analysis of guiding documents and School Delivery Plans of case study schools |

Administrative data Surveys of:

Case studies of 5 primary schools

|

Administrative data Surveys of:

Interviews with:

|

Report structure

This report is divided into five chapters.

- Chapter one describes how Counselling in Schools is being delivered in schools

- Chapter two considers whether Counselling in Schools is reaching those students who need it

- Chapter three looks at the impact of Counselling in Schools on students’ mental health

- Chapter four looks at the impact of Counselling in Schools on students’ attendance, learning and engagement

- Chapter five looks at the lessons learnt from the evaluation of Counselling in Schools.

Student mental health is strongly linked to engagement, achievement, and school attendance. Counselling in Schools - Awhi Mai, Awhi Atu is an initiative which began in 2021 with the aim of providing evidence-based counselling support. The programme was designed to enable flexibility in providing different approaches for counselling in primary and intermediate schools

This report looks at the Counselling in Schools initiative, including access to the programme, the mental health and learning and engagement outcomes for students, and the lessons learnt for implementation.

Mental health needs for children and young people are rising, and it is impacting on their learning outcomes.

Mental health for young people is getting worse. The most recent New Zealand health survey showed that significant emotional problems among 3 to 14-year-olds are increasing, from 9 percent in 2016/17 to 13 percent or 111,000 children in 2022/23. The ongoing impacts of Covid-19 are a likely driver.

Poor mental health in children impacts their educational outcomes. Good mental health is needed to enable learning and educational progress. It helps with paying attention in class and managing challenges at school. Poorer mental health effects attendance and engagement and it can lead to lower educational attainment and leaving school earlier.

The Education Review Office’s (ERO) report ‘Missing out’ on school attendance found that 46 percent of parents were likely to keep their children out of school if they have mental health challenges.

Counselling in Schools

Counselling in Schools was introduced to improve mental health outcomes for students at primary, intermediate and in some small secondary schools. It was established to improve mental health for children and young people, with mild to moderate needs, in an accessible setting on school grounds.

Counselling in Schools is available in most regions, with a particular focus on schools with the greatest need. Those schools then work with community providers to develop a counselling approach that works for their school environment and based on the needs of the school. ‘Counselling’ is used broadly, with a mixture of individual, family, group and whole-school sessions. For students who need a higher level of support, referrals are made to other services.

Why we looked at Counselling in Schools

ERO is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early learning services, schools, and kura. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports schools to provide quality education for Aotearoa New Zealand’s students.

ERO’s report on the impact of Covid-19 identified an increasing impact on student mental health, which then impacted on their education. It is important to understand how to effectively support these students, so ERO has evaluated Counselling in Schools to build the evidence base.

This report describes what we found about Counselling in Schools initiative over its three years of operation. We highlight the experiences of students who access counselling through the initiative, counsellors and providers involved, teachers and school staff who refer and have students accessing the initiative, and the parents and whānau of students receiving counselling.

This report is accompanied by a detailed technical report that provides more information on what we found, the data we draw on and how we conducted our evaluation.

What we looked at

ERO has conducted a three-phase evaluation over three years (Term 4 2021-Term 2 2024), and all three phases have informed this report. Phase One gave an early update on access to the initiative and implementation lessons. Phase Two provided another update on access and implementation of the initiative and early findings into the impacts on students’ mental health and learning and engagement. In Phase Three we looked at three key questions:

- What was the impact of the initiative on students’ wellbeing/hauora; students’ engagement and learning; and classroom behaviour?

- To what extent did the initiative increase access to counselling for primary school students? For whom? Was access equitable?

- What are some lessons learnt about implementation of this initiative?

The earlier reports can be found here:

- Phase 1 findings https://ero.govt.nz/sites/default/files/media-documents/2022-07/CiS%20summary%20of%20findings%20for%20proactive%20release.PDF

- Phase 2 findings https://ero.govt.nz/sites/default/files/media-documents/2023-06/Summary%20of%20Findings%20-%20slides.pdf

Where we looked

This report looks at the Counselling in Schools initiative within primary and intermediate schools (while the programme does operate in a small number of secondary schools, we excluded this data from our evaluation).

In this report, we use the term counsellors to refer to the practitioners who are contracted by community-based providers to schools as part of the Counselling in Schools initiative. Counselling practitioners include both practitioners who are registered with a professional body, and those who are not registered but working under the supervision of a registered counselling practitioner.

How we gathered this information

Across each phase of the evaluation, we gathered information through:

|

Phase 1 |

Phase 2 |

Phase 3 |

|

Administrative data Surveys of:

Interviews and focus groups with:

Document analysis of guiding documents and School Delivery Plans of case study schools |

Administrative data Surveys of:

Case studies of 5 primary schools

|

Administrative data Surveys of:

Interviews with:

|

Report structure

This report is divided into five chapters.

- Chapter one describes how Counselling in Schools is being delivered in schools

- Chapter two considers whether Counselling in Schools is reaching those students who need it

- Chapter three looks at the impact of Counselling in Schools on students’ mental health

- Chapter four looks at the impact of Counselling in Schools on students’ attendance, learning and engagement

- Chapter five looks at the lessons learnt from the evaluation of Counselling in Schools.

Chapter 1: How is Counselling in Schools being delivered?

Counselling in Schools has grown over time, with more providers and schools participating year on year. The programme combines several models to deliver mental health and social support to students. The number of hours received, and the accreditation of counsellors can vary from school to school.

What we did

In this chapter, we look at the different ways Counselling in Schools is delivered in schools.

This section sets out:

- Where Counselling in Schools is being delivered

- The delivery models that are used as part of Counselling in Schools

- The referral pathways that are used

- Who is delivering counselling.

What we found: An overview

Counselling in Schools has grown year on year, both in the number of providers and schools participating. In 2022, there were 141 participating schools and nine providers, in 2023 there were 215 schools and 42 providers, and in 2024 there are 243 schools and 44 providers.

The Counselling in Schools programme is a mix of models that delivers mental health and social support to students. Individual sessions make up three out of four sessions (77 percent). Fourteen percent are group sessions, and 1 percent are all of school sessions. The remainder is made up of whānau sessions (5 percent) and class sessions (3 percent).

Most schools use staff referral as their primary or only referral pathway. Three in four students (75 percent) are referred to counselling by teachers or school staff, the next most common referrer is whānau (14 percent), followed by self-referrals (4 percent).

Only three in 10 counsellors have a counselling accreditation, but nine in 10 counsellors have an accreditation. Three in 10 counsellors have a counselling accreditation, six in 10 have some other accreditation, and 15 percent have no accreditation.

1. Where is Counselling in Schools being delivered?

The Counselling in Schools programme is a mix of models that delivers mental health and social support to students.

Counselling in Schools has increased year on year, both the number of providers and schools participating. In 2022, there were 141 participating schools and nine providers, in 2023 there were 215 schools and 42 providers, and in 2024 there are 243 schools and 44 providers.

Figure 1: Number of providers and schools over time

Primary schools make up the majority of schools participating in the initiative (85 percent). Secondary schools make up 8 percent of the participating schools, whilst intermediates make up 7 percent (some intermediate aged students in Years 7-8 are in primary and secondary schools).

Figure 2: Participating schools by type

Almost all (97 percent) of schools participating in Counselling in Schools are state schools, and the remaining three percent are state integrated schools.

This evaluation looks at the impact on primary and intermediate students.

From this point forward, the analysis focuses on primary and intermediate school-aged students (Years 1–8), to fit the scope of the evaluation and allow comparisons. See technical report for further detail: https://www.evidence.ero.govt.nz/documents/technical-report-evaluation-of-counselling-in-schools

Counselling in Schools has been piloted in many regions but not all. Counselling in Schools has the most coverage in Hawkes Bay/Gisborne (48 percent of schools in that region) and Northland (28 percent of schools in that region). Counselling in Schools does not operate in Bay of Plenty or Nelson/Marlborough/West Coast and is only in three schools in the Auckland region. Regions without Counselling in Schools may access counsellors through Mana Ake (where available) or private providers, although this is not always possible due to financial or capacity limitations.

|

Region |

Participating schools |

Total schools |

|

Northland |

39 |

141 |

|

Auckland |

3 |

497 |

|

Waikato |

39 |

248 |

|

Bay of Plenty |

0 |

169 |

|

Hawkes Bay / Gisborne |

74 |

153 |

|

Taranaki / Manawatu / Whanganui |

28 |

210 |

|

Wellington |

17 |

248 |

|

Nelson / Marlborough / West Coast |

0 |

113 |

|

Canterbury |

14 |

255 |

|

Otago / Southland |

19 |

214 |

Most schools participating in Counselling in Schools are in low socioeconomic areas. Eight in 10 participating schools (78 percent) are schools in low socioeconomic areas. Just 1 percent are schools in high socioeconomic areas.

Figure 3: Schools participating in Counselling in Schools by socioeconomic area

Schools were selected in order to meet the needs of children most impacted by Covid-19 impacts and socioeconomic disadvantage. The decisions were made based on the Equity Index, as it helps to determine the number of students who are disadvantaged in each school, as well as other existing supports schools have in their community.

2. What delivery models are being used as part of Counselling in Schools?

We asked schools and providers about the different ways that counselling is delivered. We were interested in which models of referral and delivery work well, as well as challenges and barriers.

Different providers offer different types of sessions. These differ in both session type, and the number of sessions, with some providers limiting the number of sessions to six, whilst others deliver based on need and may reach a high number of hours with students who have the greatest need.

Individual sessions are the most common type of session offered by the Counselling in Schools programme, making up three in four sessions (77 percent). Individual sessions are one on one sessions with a student and a counsellor. Individual sessions are designed to allow students to develop a trusting relationship with a counsellor, talk in a safe environment, and maintain confidentiality whilst addressing issues specific to the student.

There are different types of group sessions offered, depending on the provider and the intention of the counselling. The most common is small group sessions (10 percent), involving between two and seven students. Large group sessions (4 percent) are sessions with groups of eight or more students. Group sessions are often used for lower-level needs of large groups or as appropriate for specific purposes (e.g., forming friendships, teaching accountability). Class sessions (3 percent) and whole school sessions (1 percent) are also used by some providers, although these do not happen often.

Whānau sessions are the third most common, making up 5 percent of all sessions. Whānau sessions are often used when working with parents and whānau is necessary to further understanding the case of the child, or when there is a need to create a trauma-informed response to support the child at home. These sessions usually involve whānau members coming into the school to meet with the counsellor and the student together. Based on Ministry of Education feedback, we understand that some whānau sessions occur as part of ‘individual sessions’ depending on the provider.

Figure 4: Session types

“Sometimes I am scared to talk at the start but by end I am having a really good conversation.” (Student)

“[The counsellor] also organises a girls group whom she noticed may not have friendships in the playground. So, she got them together and they make cool things together.” (School leader)

“We can get kids doing things in isolation on their own. But remember, they go back to their class and they go back to people around them. That's why I'm really big on group sessions.” (Counsellor)

3. What referral pathways are being used?

The most common way students are referred to Counselling in Schools is through referral by teachers or school staff. Three in four students (75 percent) are referred to counselling by teachers or school staff, the next most common referrer is whānau (14 percent), followed by self-referrals (4 percent).

Figure 5: Referral types

We know from our interviews that Counselling in Schools staff work regularly with school staff to build relationships and understand the process of referral. Many schools use principals as the primary referrer as teachers raise issues or suggest students that may benefit from counselling. Parents and whānau are able to find out about referral processes through school communications such as newsletters. Their contact with Counselling in Schools is comparatively limited, which likely explains the lower proportion of whānau referrals - they are less aware of the programme.

“Referrals come from us and from the families as well. And we pick those things up from conversations after school, usually parent teacher interviews. It's quite organic how that happens.” (Principal, small school)

We heard that students are more likely to refer themselves when counsellors are visible in the school, for example, at break times and home time. In some cases, the counsellor and school staff would have to visit families for consent to access the service.

“The children can turn up at my door.” (Counsellor)

“For morning tea time and the sports break I'm in there. On lunch break I'll often have an apple and walk around, so I'm accessible.” (Counsellor)

Referral works best when there is a reduction in stigma and high uptake from children, parents and whānau, and schools about counselling. This ensures multiple referral pathways, such as self, peer, and whānau referrals.

“I think some of our parents hadn't had a great time at school themselves. So, it makes them reluctant to engage with us." (School leader)

“[Parents] won't come to us. We have to go to them. We'll knock on their door. We'll phone call them if the phones work." (School leader)

ERO found some counsellors have already been employing strategies to reduce stigma through different branding of the service, advertising, allowing informal visits from children, or building trusting relationships with families.

4. Who is delivering counselling?

Only three in 10 counsellors have a counselling accreditation. Six in 10 have some other accreditation, and the remainder have no accreditation. Regardless of accreditation, over nine in 10 (94 percent) receive supervision at least monthly.

The original intent of the initiative was to have registered counsellors delivering the service. As part of design changes intended to meet community needs, the decision was made to expand the criteria to include practitioners who are registered with a professional body (for example, Counsellors; Social Workers; Occupational Therapists). In addition, to reflect the diverse contexts and needs across schools, communities and regions, practitioners who are not registered with a professional body were also included.

They are required under contract to work under the supervision of a registered counselling practitioner and to have an appropriate qualification. As part of these changes, The Ministry of Education also shifted from a more traditional version of counselling that was considered to better suit the school environment and included Rongoā Māori Practitioners or facilitators of equine therapy.

ERO found that depending on the approach of the individual provider, they seek to recruit different professionals (with different qualifications) to Counselling in Schools. We found that some providers pursue a ‘holistic approach’ and may be more likely to recruit professionals who are not accredited counsellors but have other qualifications (e.g. in occupational therapy or paediatrics). Other providers told us that they will only recruit non-counselling professionals if they have done additional counselling training. In some cases, people without counselling qualifications are recruited due to a lack of qualified candidates, particularly in areas with high demand or remote areas.

“We try to come up with what the school wants and what they feel would be important. So there's no real strong differentiation in the type of provision, be it arts therapy, occupational therapy or counsellor. It's more about the type of person and matching to the school.” (Provider)

“For some schools [in a rural place] it's notoriously hard to find a counsellor.” (Provider)

We did not have sufficient data from this evaluation to determine if qualifications of counsellors made a difference. Overseas research on school counselling (107 studies) shows a significant improvement in quality when counselling interventions are delivered by licensed professionals.

Conclusion

Counselling in Schools is delivered in varied ways across the country to meet the needs of the children it serves, and reflecting the practical realities of the school it operates in.

The programme is a mix of models that delivers mental health and social support to students, with a mixture of individual, group, whānau and whole of school settings. Most schools use staff referral as their primary or only referral pathway. Only three in 10 counsellors have a counselling accreditation.

Counselling in Schools has grown over time, with more providers and schools participating year on year. The programme combines several models to deliver mental health and social support to students. The number of hours received, and the accreditation of counsellors can vary from school to school.

What we did

In this chapter, we look at the different ways Counselling in Schools is delivered in schools.

This section sets out:

- Where Counselling in Schools is being delivered

- The delivery models that are used as part of Counselling in Schools

- The referral pathways that are used

- Who is delivering counselling.

What we found: An overview

Counselling in Schools has grown year on year, both in the number of providers and schools participating. In 2022, there were 141 participating schools and nine providers, in 2023 there were 215 schools and 42 providers, and in 2024 there are 243 schools and 44 providers.

The Counselling in Schools programme is a mix of models that delivers mental health and social support to students. Individual sessions make up three out of four sessions (77 percent). Fourteen percent are group sessions, and 1 percent are all of school sessions. The remainder is made up of whānau sessions (5 percent) and class sessions (3 percent).

Most schools use staff referral as their primary or only referral pathway. Three in four students (75 percent) are referred to counselling by teachers or school staff, the next most common referrer is whānau (14 percent), followed by self-referrals (4 percent).

Only three in 10 counsellors have a counselling accreditation, but nine in 10 counsellors have an accreditation. Three in 10 counsellors have a counselling accreditation, six in 10 have some other accreditation, and 15 percent have no accreditation.

1. Where is Counselling in Schools being delivered?

The Counselling in Schools programme is a mix of models that delivers mental health and social support to students.

Counselling in Schools has increased year on year, both the number of providers and schools participating. In 2022, there were 141 participating schools and nine providers, in 2023 there were 215 schools and 42 providers, and in 2024 there are 243 schools and 44 providers.

Figure 1: Number of providers and schools over time

Primary schools make up the majority of schools participating in the initiative (85 percent). Secondary schools make up 8 percent of the participating schools, whilst intermediates make up 7 percent (some intermediate aged students in Years 7-8 are in primary and secondary schools).

Figure 2: Participating schools by type

Almost all (97 percent) of schools participating in Counselling in Schools are state schools, and the remaining three percent are state integrated schools.

This evaluation looks at the impact on primary and intermediate students.

From this point forward, the analysis focuses on primary and intermediate school-aged students (Years 1–8), to fit the scope of the evaluation and allow comparisons. See technical report for further detail: https://www.evidence.ero.govt.nz/documents/technical-report-evaluation-of-counselling-in-schools

Counselling in Schools has been piloted in many regions but not all. Counselling in Schools has the most coverage in Hawkes Bay/Gisborne (48 percent of schools in that region) and Northland (28 percent of schools in that region). Counselling in Schools does not operate in Bay of Plenty or Nelson/Marlborough/West Coast and is only in three schools in the Auckland region. Regions without Counselling in Schools may access counsellors through Mana Ake (where available) or private providers, although this is not always possible due to financial or capacity limitations.

|

Region |

Participating schools |

Total schools |

|

Northland |

39 |

141 |

|

Auckland |

3 |

497 |

|

Waikato |

39 |

248 |

|

Bay of Plenty |

0 |

169 |

|

Hawkes Bay / Gisborne |

74 |

153 |

|

Taranaki / Manawatu / Whanganui |

28 |

210 |

|

Wellington |

17 |

248 |

|

Nelson / Marlborough / West Coast |

0 |

113 |

|

Canterbury |

14 |

255 |

|

Otago / Southland |

19 |

214 |

Most schools participating in Counselling in Schools are in low socioeconomic areas. Eight in 10 participating schools (78 percent) are schools in low socioeconomic areas. Just 1 percent are schools in high socioeconomic areas.

Figure 3: Schools participating in Counselling in Schools by socioeconomic area

Schools were selected in order to meet the needs of children most impacted by Covid-19 impacts and socioeconomic disadvantage. The decisions were made based on the Equity Index, as it helps to determine the number of students who are disadvantaged in each school, as well as other existing supports schools have in their community.

2. What delivery models are being used as part of Counselling in Schools?

We asked schools and providers about the different ways that counselling is delivered. We were interested in which models of referral and delivery work well, as well as challenges and barriers.

Different providers offer different types of sessions. These differ in both session type, and the number of sessions, with some providers limiting the number of sessions to six, whilst others deliver based on need and may reach a high number of hours with students who have the greatest need.

Individual sessions are the most common type of session offered by the Counselling in Schools programme, making up three in four sessions (77 percent). Individual sessions are one on one sessions with a student and a counsellor. Individual sessions are designed to allow students to develop a trusting relationship with a counsellor, talk in a safe environment, and maintain confidentiality whilst addressing issues specific to the student.

There are different types of group sessions offered, depending on the provider and the intention of the counselling. The most common is small group sessions (10 percent), involving between two and seven students. Large group sessions (4 percent) are sessions with groups of eight or more students. Group sessions are often used for lower-level needs of large groups or as appropriate for specific purposes (e.g., forming friendships, teaching accountability). Class sessions (3 percent) and whole school sessions (1 percent) are also used by some providers, although these do not happen often.

Whānau sessions are the third most common, making up 5 percent of all sessions. Whānau sessions are often used when working with parents and whānau is necessary to further understanding the case of the child, or when there is a need to create a trauma-informed response to support the child at home. These sessions usually involve whānau members coming into the school to meet with the counsellor and the student together. Based on Ministry of Education feedback, we understand that some whānau sessions occur as part of ‘individual sessions’ depending on the provider.

Figure 4: Session types

“Sometimes I am scared to talk at the start but by end I am having a really good conversation.” (Student)

“[The counsellor] also organises a girls group whom she noticed may not have friendships in the playground. So, she got them together and they make cool things together.” (School leader)

“We can get kids doing things in isolation on their own. But remember, they go back to their class and they go back to people around them. That's why I'm really big on group sessions.” (Counsellor)

3. What referral pathways are being used?

The most common way students are referred to Counselling in Schools is through referral by teachers or school staff. Three in four students (75 percent) are referred to counselling by teachers or school staff, the next most common referrer is whānau (14 percent), followed by self-referrals (4 percent).

Figure 5: Referral types

We know from our interviews that Counselling in Schools staff work regularly with school staff to build relationships and understand the process of referral. Many schools use principals as the primary referrer as teachers raise issues or suggest students that may benefit from counselling. Parents and whānau are able to find out about referral processes through school communications such as newsletters. Their contact with Counselling in Schools is comparatively limited, which likely explains the lower proportion of whānau referrals - they are less aware of the programme.

“Referrals come from us and from the families as well. And we pick those things up from conversations after school, usually parent teacher interviews. It's quite organic how that happens.” (Principal, small school)

We heard that students are more likely to refer themselves when counsellors are visible in the school, for example, at break times and home time. In some cases, the counsellor and school staff would have to visit families for consent to access the service.

“The children can turn up at my door.” (Counsellor)

“For morning tea time and the sports break I'm in there. On lunch break I'll often have an apple and walk around, so I'm accessible.” (Counsellor)

Referral works best when there is a reduction in stigma and high uptake from children, parents and whānau, and schools about counselling. This ensures multiple referral pathways, such as self, peer, and whānau referrals.

“I think some of our parents hadn't had a great time at school themselves. So, it makes them reluctant to engage with us." (School leader)

“[Parents] won't come to us. We have to go to them. We'll knock on their door. We'll phone call them if the phones work." (School leader)

ERO found some counsellors have already been employing strategies to reduce stigma through different branding of the service, advertising, allowing informal visits from children, or building trusting relationships with families.

4. Who is delivering counselling?

Only three in 10 counsellors have a counselling accreditation. Six in 10 have some other accreditation, and the remainder have no accreditation. Regardless of accreditation, over nine in 10 (94 percent) receive supervision at least monthly.

The original intent of the initiative was to have registered counsellors delivering the service. As part of design changes intended to meet community needs, the decision was made to expand the criteria to include practitioners who are registered with a professional body (for example, Counsellors; Social Workers; Occupational Therapists). In addition, to reflect the diverse contexts and needs across schools, communities and regions, practitioners who are not registered with a professional body were also included.

They are required under contract to work under the supervision of a registered counselling practitioner and to have an appropriate qualification. As part of these changes, The Ministry of Education also shifted from a more traditional version of counselling that was considered to better suit the school environment and included Rongoā Māori Practitioners or facilitators of equine therapy.

ERO found that depending on the approach of the individual provider, they seek to recruit different professionals (with different qualifications) to Counselling in Schools. We found that some providers pursue a ‘holistic approach’ and may be more likely to recruit professionals who are not accredited counsellors but have other qualifications (e.g. in occupational therapy or paediatrics). Other providers told us that they will only recruit non-counselling professionals if they have done additional counselling training. In some cases, people without counselling qualifications are recruited due to a lack of qualified candidates, particularly in areas with high demand or remote areas.

“We try to come up with what the school wants and what they feel would be important. So there's no real strong differentiation in the type of provision, be it arts therapy, occupational therapy or counsellor. It's more about the type of person and matching to the school.” (Provider)

“For some schools [in a rural place] it's notoriously hard to find a counsellor.” (Provider)

We did not have sufficient data from this evaluation to determine if qualifications of counsellors made a difference. Overseas research on school counselling (107 studies) shows a significant improvement in quality when counselling interventions are delivered by licensed professionals.

Conclusion

Counselling in Schools is delivered in varied ways across the country to meet the needs of the children it serves, and reflecting the practical realities of the school it operates in.

The programme is a mix of models that delivers mental health and social support to students, with a mixture of individual, group, whānau and whole of school settings. Most schools use staff referral as their primary or only referral pathway. Only three in 10 counsellors have a counselling accreditation.

Chapter 2: Is Counselling in Schools reaching the children who need it?

Counselling in Schools is intended to reach children and young people with mild to moderate mental health needs, particularly in schools in lower socioeconomic areas. We have found it is successful in achieving that.

What we did

In this chapter, we look at whether Counselling in Schools is reaching the students who need support by examining student and school characteristics based on administrative data, survey data and focus group discussions.

This section sets out:

- the age of students accessing counselling

- the socioeconomic context of students accessing counselling

- psychological needs of children accessing counselling

- the ethnicity of students accessing counselling

- the gender of students accessing counselling.

What we found: an overview

The programme reaches primary school students who are in psychological distress. Seven in 10 (71 percent) of students entering counselling meet the ‘clinical cutoff’ for distress.

The programme may not reach students who do not exhibit signs of distress. Three-quarters of referrals to counsellors are made by school staff, and one-quarter of students were referred due to their behaviour.

The programme is reaching students in low socioeconomic areas. Eight in 10 participating schools (78 percent) are schools in low socioeconomic areas. Just 1 percent are schools in high socioeconomic areas.

It reaches some groups who do not typically access counselling, such as Māori students and boys. Fifty-five percent of those accessing Counselling in Schools are boys and 45 percent are girls. Six in 10 students (60 percent) accessing Counselling in Schools identify as Māori, similar to the average Māori roll for schools enrolled in the programme (58 percent).

It reaches lower numbers of Asian, Pacific, and MELAA (Middle Eastern, Latin American, African) students. Pacific students make up 8 percent of those accessing Counselling in Schools, less than the school roll of 14 percent. Asian students make up only 2 percent of those accessing the service yet make up seven percent of the roll. MELAA students make up one percent of those accessing Counselling in Schools and 2 percent of the school roll.

1. How old are the students accessing counselling?

Counselling in schools is most commonly accessed by students in Year 5 to 8. One in three students (33 percent) accessing counselling are in Year 7 or 8, and another one in three (31 percent) are in Year 5 or 6. Thirteen percent are in Years 1 or 2 and 23 percent are in Years 3 or 4.

Figure 6: Students accessing Counselling in Schools by year group

2. What is the socioeconomic context of students accessing counselling?

Most students participating in Counselling in Schools are in low socioeconomic areas. Eight in 10 participating schools (78 percent) are schools in low socioeconomic areas. Just 1 percent are schools in high socioeconomic areas. See Chapter 1 for more information.

Typically, students in low socioeconomic areas are from more disadvantaged areas, and there is a correlation between child poverty and increased levels of mental health need.

3. What are the psychological needs of children accessing counselling?

Most students are entering counselling with higher mental health needs. Seven in 10 (71 percent) of students entering counselling meet the ‘clinical cutoff’ for distress3, as indicated by their pre-counselling score on the Child Outcome Rating Scale (CORS). This indicates that Counselling in Schools is successfully reaching children with mental health needs.

The programme may not reach students who do not exhibit signs of distress. Students are referred to Counselling in Schools for a range of reasons and are often referred for more than one reason. We also heard that there can be many factors underlying a referral, which is not captured by the referral reason.

The most common reasons for referral to Counselling in Schools are behaviour, anxiety, stress, or trauma, and relationships. The top three referral reasons are:

- behaviour (24 percent)

- anxiety, stress, or trauma (16 percent)

- relationships (15 percent).

Figure 7: Referral reasons

We found that behaviour is key referral reason because it is easily observable, and it impacts others in the school. Less observable issues, like grief and loss, are more likely to be picked up where schools have built a trusting relationship with parents and whānau, but they can be missed.

“Every child is evaluated on a needs-basis, from the behaviours that they were displaying and the level of disruption they were causing. If someone's really highly in need, they'll be prioritised over other people.” (Teacher)

4. What are the ethnicities of students accessing counselling?

Māori and NZ European/Aotearoa students are accessing Counselling in Schools at levels comparable to or above the school roll. Six in 10 students (60 percent) accessing Counselling in Schools identify as Māori, similar to the average Māori roll for schools enrolled in the programme (58 percent). This may reflect the referral processes working for Māori, although it is worth noting that Māori students are more likely to have mental health needs. Nearly half (47 percent) identify as NZ European/Pākehā, compared to 41 percent of the school roll.

Pacific, Asian and MELAA students are less likely to attend Counselling in Schools. Pacific students make up 8 percent of those accessing Counselling in Schools, less than the school roll of 14 percent. Asian students make up only 2 percent of those accessing the service yet make up 7 percent of the roll. MELAA students make up 1 percent of those accessing Counselling in Schools and 2 percent of the school roll.

The lower uptake of Counselling in Schools by Pacific, Asian, and MELAA students may indicate that more responsive approaches are needed to ensure that students of these ethnicities are being supported with mental health challenges. Other research has identified that this is common among mental health service access, and identifies an opportunity to strengthen counselling in schools delivery.

|

Ethnicity |

Receiving Counselling in Schools |

Total roll of participating schools |

|

Māori |

60% |

58% |

|

NZ European /Pākehā |

47% |

41% |

|

Pacific |

8% |

14% |

|

Asian |

2% |

7% |

|

MELAA |

1% |

2% |

5. What gender are the students accessing counselling?

Boys are slightly more likely to access Counselling in Schools than girls. Fifty-five percent of those accessing Counselling in Schools are boys and 45 percent are girls.

Figure 8: Students accessing Counselling in Schools by gender

School staff most commonly refer to Counselling in Schools for observable issues, such as behaviour (the most common referral reason). This likely contributes to more boys accessing Counselling in Schools than girls as boys are twice as likely to be referred for behaviour compared to girls. One in three boys (33 percent) are referred to counselling for behaviour, compared to 16 percent of girls.

Figure 9: Percentage of referrals for behaviour, by gender

Conclusion

Counselling in Schools is successfully reaching primary school students who are in mental health distress.

It reaches some groups who do not typically access counselling, such as Māori students and boys, but is less successful in reaching Asian, Pacific, and MELAA students.

Counselling in Schools is intended to reach children and young people with mild to moderate mental health needs, particularly in schools in lower socioeconomic areas. We have found it is successful in achieving that.

What we did

In this chapter, we look at whether Counselling in Schools is reaching the students who need support by examining student and school characteristics based on administrative data, survey data and focus group discussions.

This section sets out:

- the age of students accessing counselling

- the socioeconomic context of students accessing counselling

- psychological needs of children accessing counselling

- the ethnicity of students accessing counselling

- the gender of students accessing counselling.

What we found: an overview

The programme reaches primary school students who are in psychological distress. Seven in 10 (71 percent) of students entering counselling meet the ‘clinical cutoff’ for distress.

The programme may not reach students who do not exhibit signs of distress. Three-quarters of referrals to counsellors are made by school staff, and one-quarter of students were referred due to their behaviour.

The programme is reaching students in low socioeconomic areas. Eight in 10 participating schools (78 percent) are schools in low socioeconomic areas. Just 1 percent are schools in high socioeconomic areas.

It reaches some groups who do not typically access counselling, such as Māori students and boys. Fifty-five percent of those accessing Counselling in Schools are boys and 45 percent are girls. Six in 10 students (60 percent) accessing Counselling in Schools identify as Māori, similar to the average Māori roll for schools enrolled in the programme (58 percent).

It reaches lower numbers of Asian, Pacific, and MELAA (Middle Eastern, Latin American, African) students. Pacific students make up 8 percent of those accessing Counselling in Schools, less than the school roll of 14 percent. Asian students make up only 2 percent of those accessing the service yet make up seven percent of the roll. MELAA students make up one percent of those accessing Counselling in Schools and 2 percent of the school roll.

1. How old are the students accessing counselling?

Counselling in schools is most commonly accessed by students in Year 5 to 8. One in three students (33 percent) accessing counselling are in Year 7 or 8, and another one in three (31 percent) are in Year 5 or 6. Thirteen percent are in Years 1 or 2 and 23 percent are in Years 3 or 4.

Figure 6: Students accessing Counselling in Schools by year group

2. What is the socioeconomic context of students accessing counselling?

Most students participating in Counselling in Schools are in low socioeconomic areas. Eight in 10 participating schools (78 percent) are schools in low socioeconomic areas. Just 1 percent are schools in high socioeconomic areas. See Chapter 1 for more information.

Typically, students in low socioeconomic areas are from more disadvantaged areas, and there is a correlation between child poverty and increased levels of mental health need.

3. What are the psychological needs of children accessing counselling?

Most students are entering counselling with higher mental health needs. Seven in 10 (71 percent) of students entering counselling meet the ‘clinical cutoff’ for distress3, as indicated by their pre-counselling score on the Child Outcome Rating Scale (CORS). This indicates that Counselling in Schools is successfully reaching children with mental health needs.

The programme may not reach students who do not exhibit signs of distress. Students are referred to Counselling in Schools for a range of reasons and are often referred for more than one reason. We also heard that there can be many factors underlying a referral, which is not captured by the referral reason.

The most common reasons for referral to Counselling in Schools are behaviour, anxiety, stress, or trauma, and relationships. The top three referral reasons are:

- behaviour (24 percent)

- anxiety, stress, or trauma (16 percent)

- relationships (15 percent).

Figure 7: Referral reasons

We found that behaviour is key referral reason because it is easily observable, and it impacts others in the school. Less observable issues, like grief and loss, are more likely to be picked up where schools have built a trusting relationship with parents and whānau, but they can be missed.

“Every child is evaluated on a needs-basis, from the behaviours that they were displaying and the level of disruption they were causing. If someone's really highly in need, they'll be prioritised over other people.” (Teacher)

4. What are the ethnicities of students accessing counselling?

Māori and NZ European/Aotearoa students are accessing Counselling in Schools at levels comparable to or above the school roll. Six in 10 students (60 percent) accessing Counselling in Schools identify as Māori, similar to the average Māori roll for schools enrolled in the programme (58 percent). This may reflect the referral processes working for Māori, although it is worth noting that Māori students are more likely to have mental health needs. Nearly half (47 percent) identify as NZ European/Pākehā, compared to 41 percent of the school roll.