Related insights

Explore related documents that you might be interested in.

Read Online

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank all the young people, parents and whānau, school leaders and teachers, and others who shared their experiences, views and insights through interviews, groups discussions and surveys. We thank you for giving your time so that others may benefit from your stories about what has and hasn’t worked. We thank you openly and whole-heartedly.

We give generous thanks to the 11 schools that accommodated out research team on visits, organising time in their school day for us to talk to students, teachers, and leaders. We know your time is precious.

We give special thanks to the kaumatua who talked to us about the relationship his hapū has formed with one of these school, and how this had led to a collaboration helping the school implement the new ANZ Histories content.

We thank the Ministry of Education who have been our partners for this evaluation. We have received a huge amount of support from Ministry staff who have guided us on the refresh of the NZ Curriculum and provided practical support to undertake the evaluation.

We also thank the many experts who have shared their understandings of Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories and the Social Sciences with us, as well as other important subject matter. We particularly acknowledge the members of our ‘Expert Advisory Group’ who shared their knowledge and wisdom to help guide our evaluation and make sense of the emerging findings.

We acknowledge and thank all the young people, parents and whānau, school leaders and teachers, and others who shared their experiences, views and insights through interviews, groups discussions and surveys. We thank you for giving your time so that others may benefit from your stories about what has and hasn’t worked. We thank you openly and whole-heartedly.

We give generous thanks to the 11 schools that accommodated out research team on visits, organising time in their school day for us to talk to students, teachers, and leaders. We know your time is precious.

We give special thanks to the kaumatua who talked to us about the relationship his hapū has formed with one of these school, and how this had led to a collaboration helping the school implement the new ANZ Histories content.

We thank the Ministry of Education who have been our partners for this evaluation. We have received a huge amount of support from Ministry staff who have guided us on the refresh of the NZ Curriculum and provided practical support to undertake the evaluation.

We also thank the many experts who have shared their understandings of Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories and the Social Sciences with us, as well as other important subject matter. We particularly acknowledge the members of our ‘Expert Advisory Group’ who shared their knowledge and wisdom to help guide our evaluation and make sense of the emerging findings.

Executive summary

In 2023, teaching Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories (ANZ Histories) became compulsory for students in Years 1-10. ANZ Histories is part of the refreshed Social Sciences learning area. The Education Review Office, in partnership with the Ministry of Education, wanted to know how the implementation of ANZ Histories and the wider Social Sciences is going.

This report describes what we found about the changes and the impacts for students, teachers, and parents and whānau. It also describes the lessons that can help inform the ongoing implementation of the Refreshed Curriculum.

What is Social Sciences and why is it important?

Social Sciences, sometimes referred to as Social Studies in primary schools, is the study of how societies work, both now, in the past and in the future. Social Sciences include subject areas like history, geography, economics, psychology, sociology, and media studies that students can specialise in, typically at senior secondary school. Students learn about:

- how societies work

- the past, present, and future

- people, places, cultures, histories, and the economic world within and beyond Aotearoa New Zealand.

In doing so, the Social Sciences helps students develop knowledge and skills to understand, participate in and contribute to local, national, and global communities.

What is Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories?

Learning about ANZ Histories builds understanding about how Māori and all people who have, or now, call Aotearoa New Zealand home, have shaped Aotearoa New Zealand’s past. Understanding the past helps students critically evaluate what is happening now, and what may happen in the future.

ANZ Histories content is intended to teach students to ‘understand’ big ideas about ANZ Histories, to ‘know’ the historical context, and to be able to ‘do’ practices such as thinking, evaluating, and communicating historical information.

What has changed in Social Sciences, including Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories?

Te Ao Tangata | the refreshed Social Sciences (Social Sciences) is the first learning area to be made available to schools as part of Te Mātaiaho | the Refreshed New Zealand Curriculum (the Refreshed Curriculum). Only ANZ Histories, which is a part of the refreshed Social Sciences, became compulsory for students in Years 1-10 from the beginning of 2023. Teaching the wider refreshed Social Sciences is not required until 2027.

As part of the Refreshed Curriculum, the Understand, Know, Do framework has been introduced to be clearer about the ‘learning that matters’ and to specify that learning needs to cover subject knowledge, as well as competencies and skills. Additionally, progress outcomes have replaced the previous achievement objectives.

What we looked at

ERO’s evaluation focused on the implementation of ANZ Histories within the refreshed Social Sciences learning area. We set out to answer the following questions:

- What is being taught for ANZ Histories?

- What has been the impact of ANZ Histories on students, teachers, and communities?

- What has been working well and less well in making the changes to include ANZ Histories?

- What is being taught for the refreshed Social Sciences learning area more broadly, and what impact is it having?

- What are the lessons for ANZ Histories and for implementing other curriculum areas?

Where we looked

We have taken a robust, mixed-methods approach to deliver breadth and depth, including:

- site visits at 11 schools

- surveys of 447 school leaders and teachers

- surveys of 918 students

- surveys of 1,016 parents and whānau

- in-depth interviews with school leaders, teachers, students, parents and whānau, experts in curriculum and/or relevant subject matter, and one kaumatua of a hapū.

We collected our data in late Term 3 and early Term 4 of 2023.

Key Findings

ERO identified key findings across four areas:

- what is being taught

- impact on students

- impact for teachers

- impact on parents and whānau.

Our findings focus on ANZ Histories because this is required to be taught and is where most of the change is happening. We found limited change for the wider refreshed Social Sciences.

Area 1: What is being taught?

It has been compulsory for less than a year and not all year levels are yet being taught ANZ Histories, and not all of the content is being taught. Schools are prioritising local and Māori histories and teaching ANZ Histories over Social Sciences.

Finding 1: ANZ Histories became compulsory at the start of 2023. Three-quarters of schools are teaching it at all year levels. Primary schools are more likely to be teaching it. Schools are prioritising implementing ANZ Histories, to avoid overwhelming teachers, and this is crowding out other areas of Social Sciences.

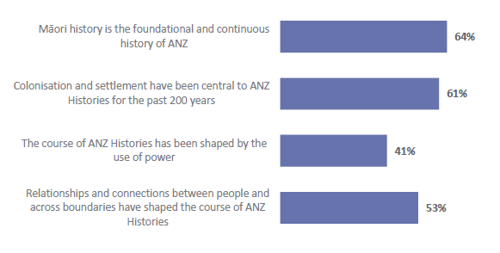

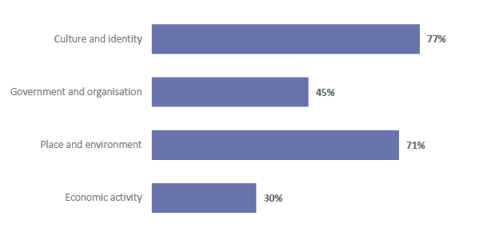

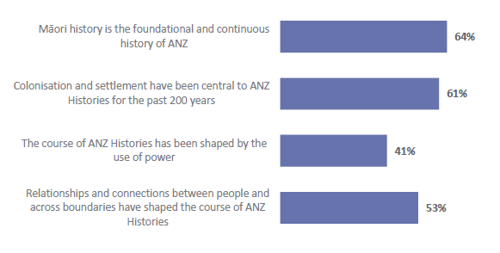

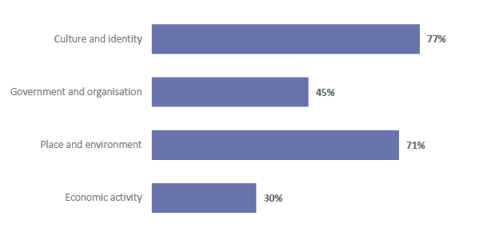

Finding 2: Of the four ‘Understands’ (big ideas), schools are prioritising teaching Māori history (64 percent teaching this) and colonisation (61 percent) more than relationships across boundaries and people (53 percent), and the use of power (41 percent). In terms of the ‘Know’ (contexts), schools have had a much stronger focus on teaching about culture and identity (77 percent), and place and environment (71 percent) than about government and organisation (45 percent) and economic activity (30 percent).

Finding 3: The curriculum statements are being interpreted by schools so that they are focusing on local histories rather than national events, and local is sometimes interpreted as only Māori histories. Schools are also teaching less about global contexts.

Finding 4: Teachers need to weave Understand, Know, and Do together but are not yet able to do that and are mainly focusing on the Know. Both primary and secondary schools told us that the Do inquiry practices are not yet a focus in their teaching of ANZ Histories. This matters because the inquiry practices help students to be critical thinkers.

Area 2: Impact on students

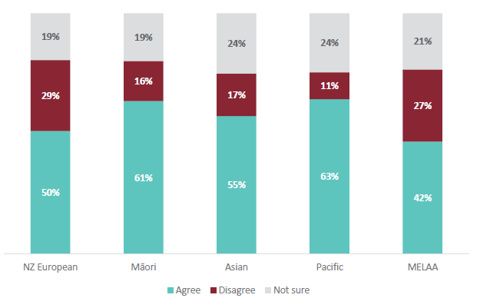

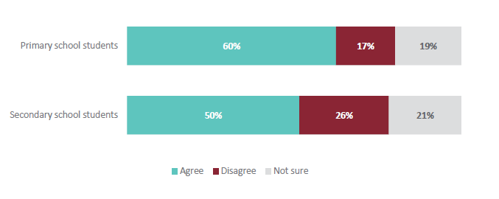

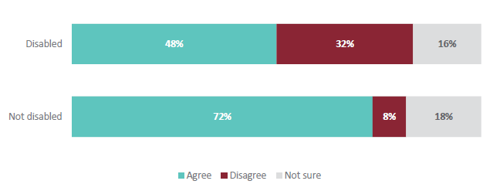

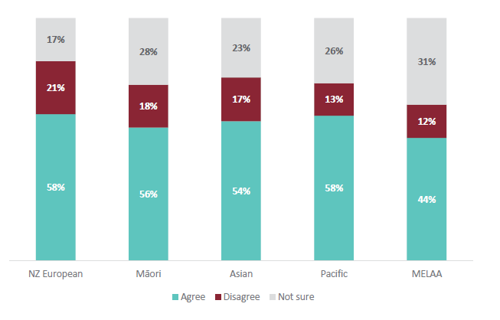

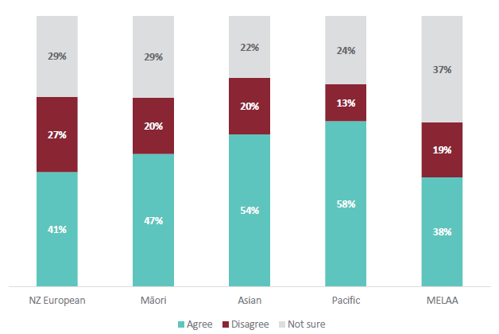

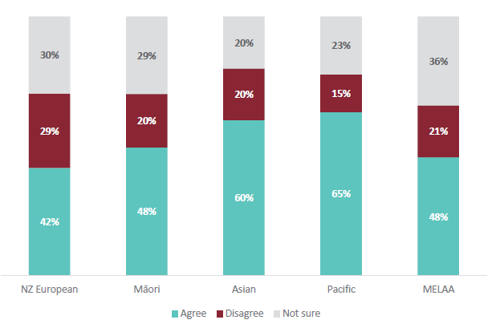

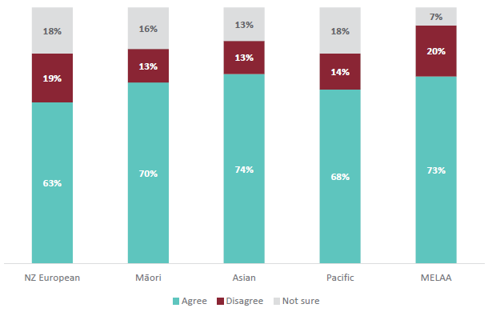

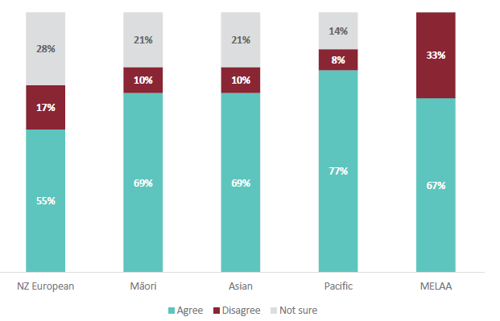

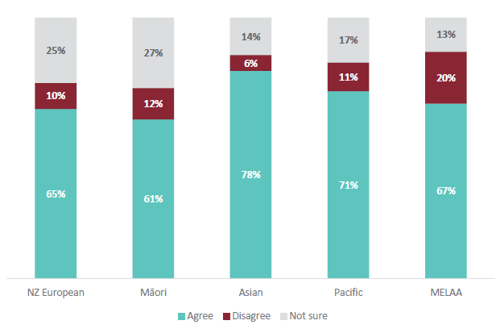

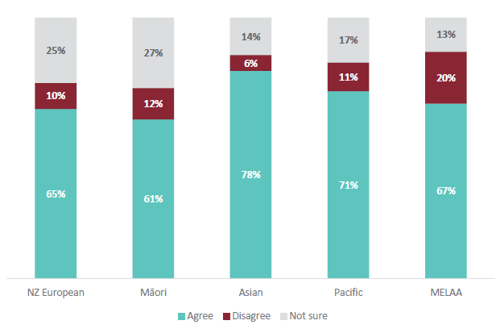

Half of students enjoy learning about ANZ Histories. Students enjoy ANZ Histories more when it includes global contexts and when they are learning about people similar to them. The focus on Māori and Pacific history means Māori and Pacific students are enjoying ANZ Histories more than NZ European, Asian, and MELAA students.

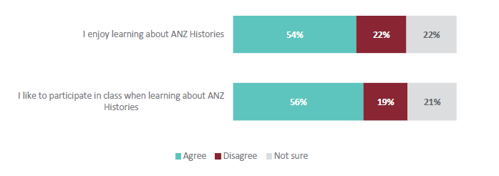

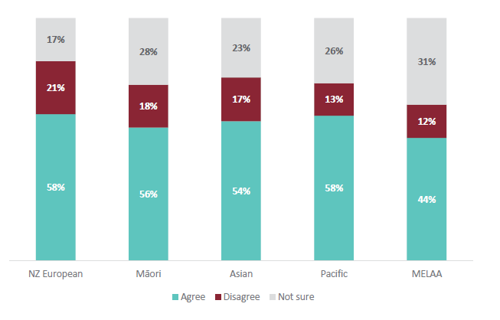

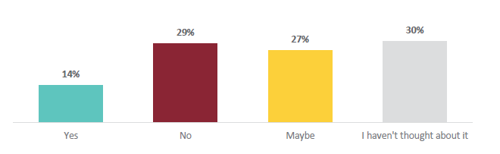

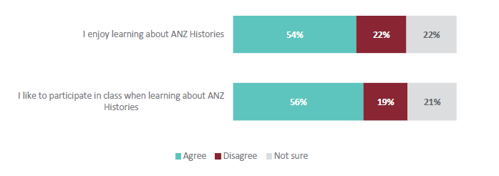

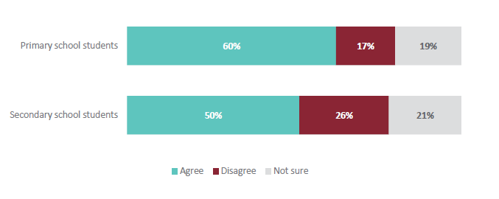

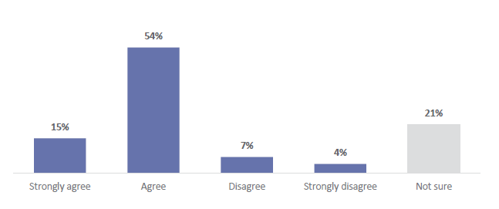

Finding 5: Teaching ANZ Histories has been compulsory for less than a year. At this stage, just over half of students enjoy learning about ANZ Histories. Two-thirds of teachers have seen positive impacts on student participation.

Finding 6: It’s important to retain a link to global contexts and events. Students are more than twice as likely to enjoy ANZ Histories when they are learning about New Zealand’s place in the world.

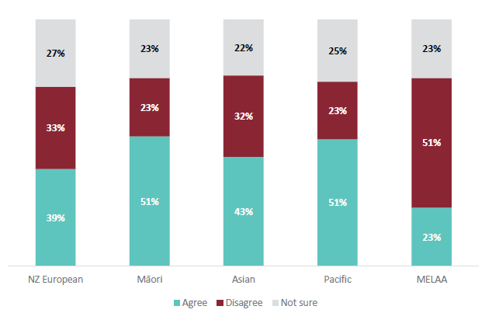

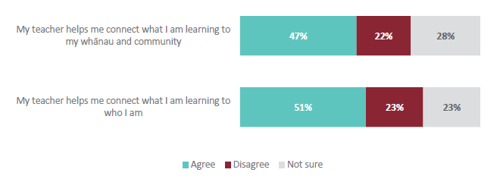

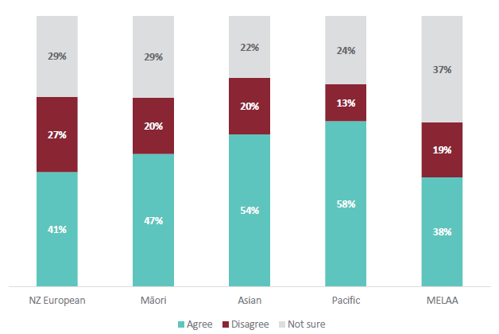

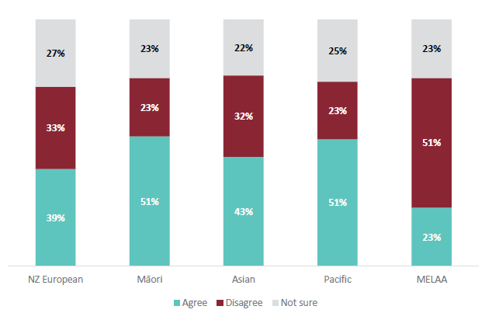

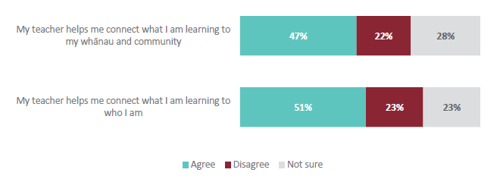

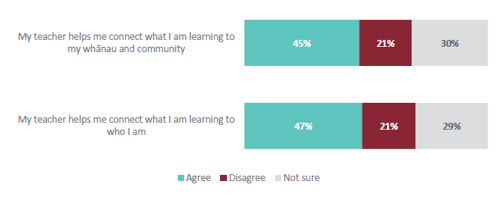

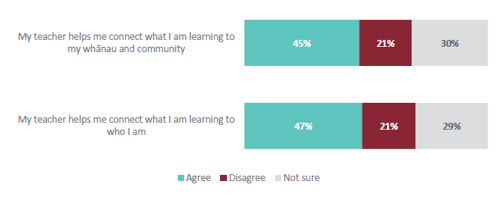

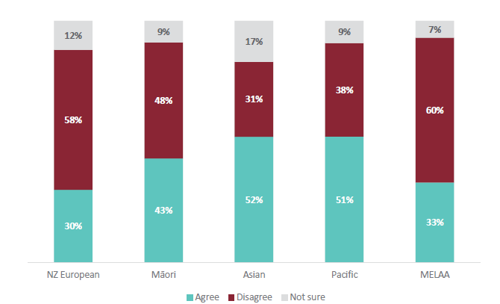

Finding 7: Students are twice as likely to enjoy ANZ Histories when their learning is connecting them to their whānau and community, and when they are learning about people similar to them. Half of Māori and Pacific students (51 percent) report learning about people similar to them in ANZ Histories, but only two-fifths of Asian (43 percent) and NZ European (39 percent) students, and only a quarter (23 percent) of MELAA students do.

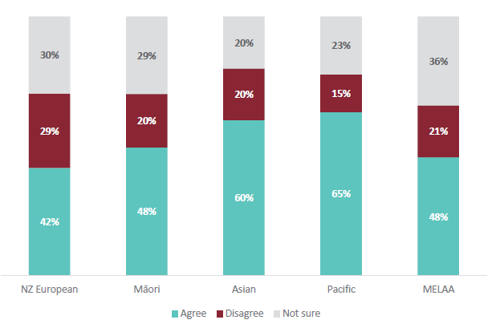

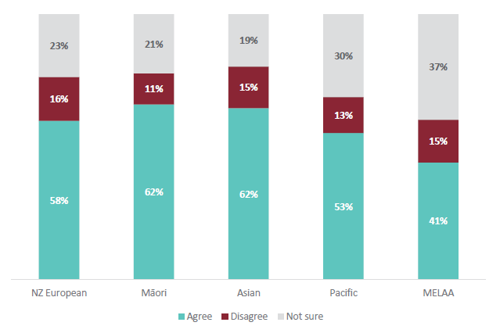

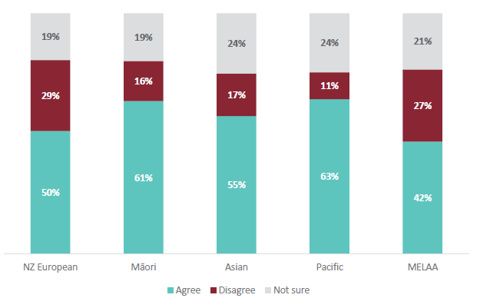

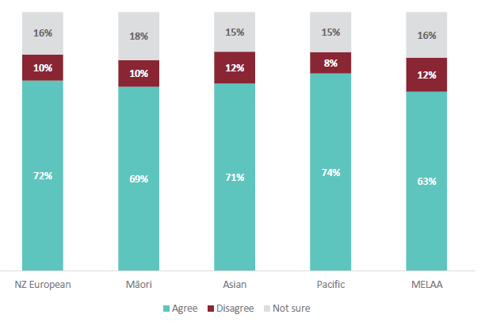

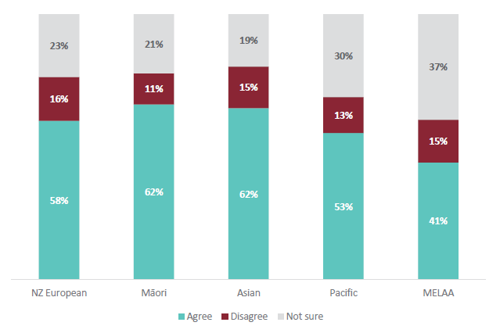

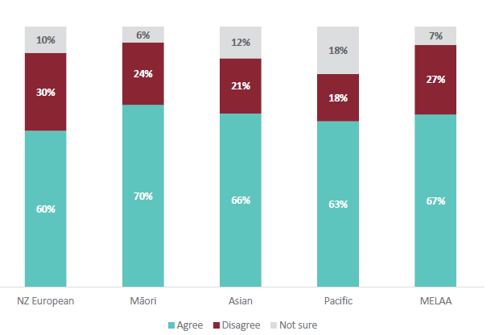

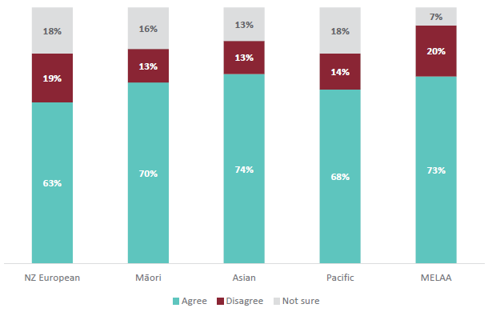

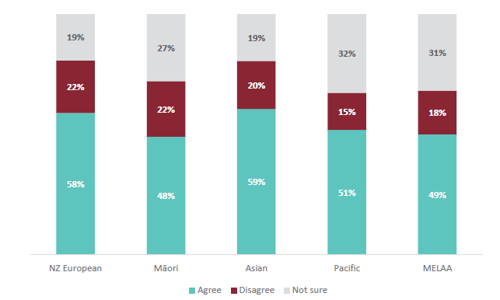

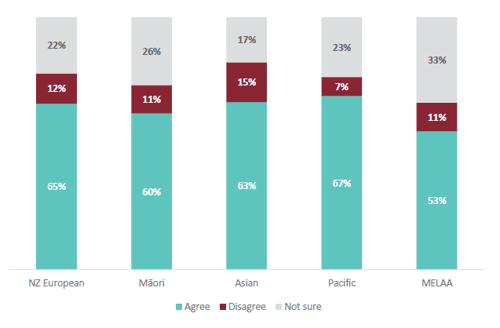

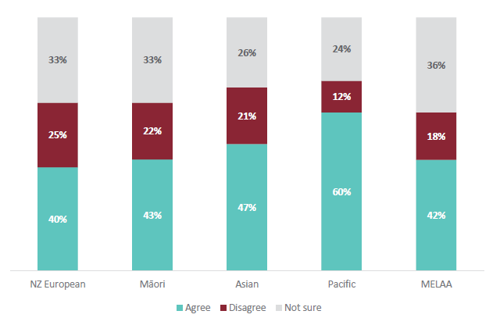

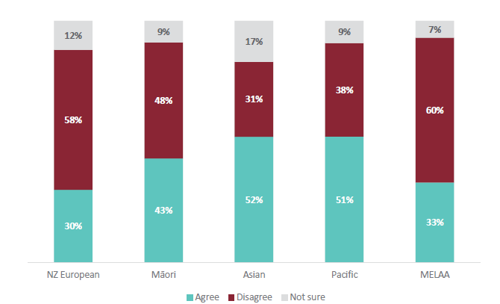

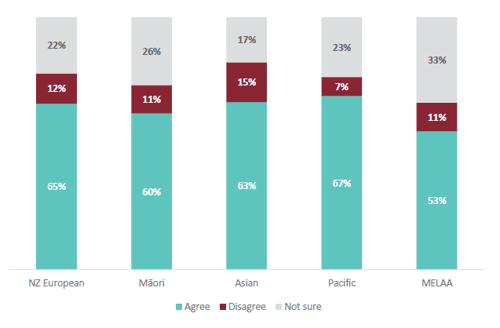

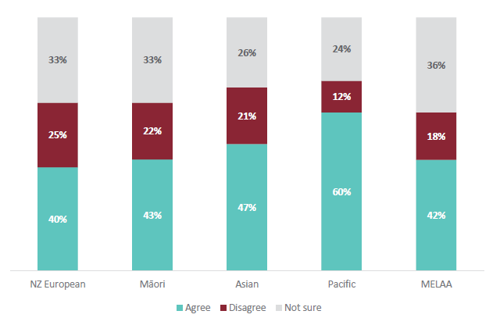

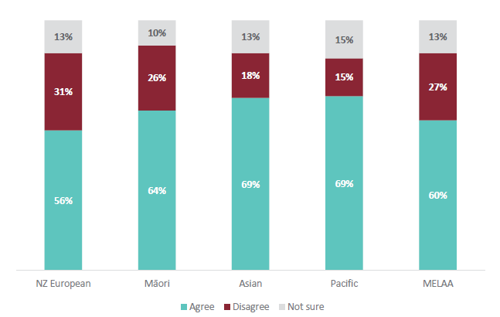

Finding 8: Enjoyment of learning ANZ Histories is not the same for all ethnicities. While almost two-thirds of Pacific students enjoy ANZ Histories (63 percent) and the majority of Māori students are also enjoying it (61 percent), fewer Asian students (55 percent), only half of NZ European students (50 percent), and less than half of MELAA students (42 percent) enjoy it.

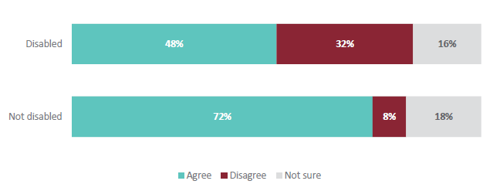

Finding 9: It is too early to measure the progress students are making in their learning in ANZ Histories. But nearly two in five students either aren’t sure or don’t think they are making progress in ANZ Histories. Some teachers are unclear on how to track progress.

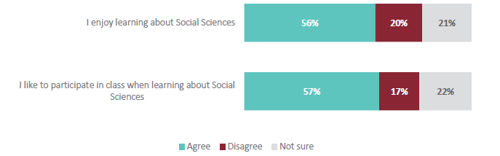

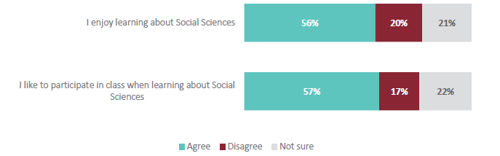

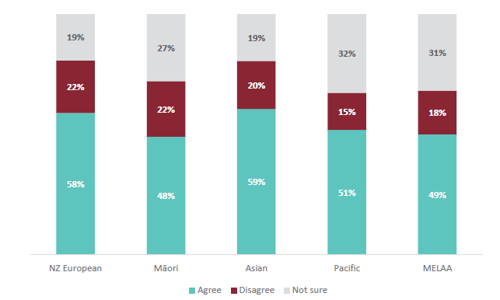

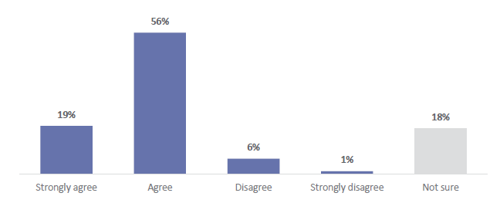

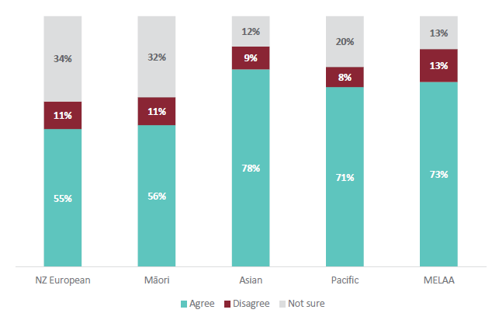

Finding 10: Similar to ANZ Histories, more than half of students enjoy learning (56 percent) and like to participate (57 percent) in learning about Social Sciences. Asian and NZ European students are enjoying Social Sciences the most, and MELAA and Māori students the least, which is different to ANZ Histories.

Area 3: Impact on school leaders and teachers

Teachers like teaching ANZ Histories, but some are overwhelmed by the scale of change and they don’t have the skills or time needed to develop a local curriculum.

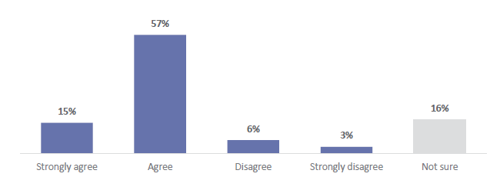

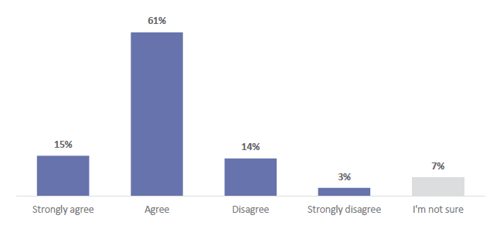

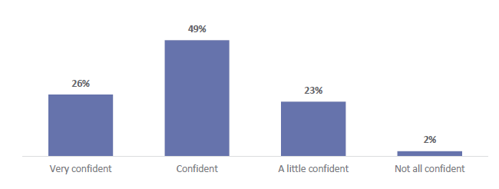

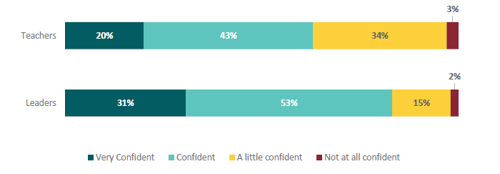

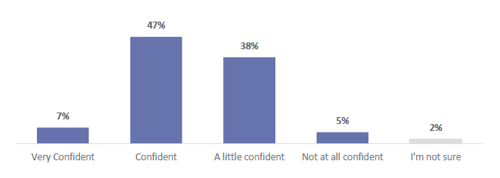

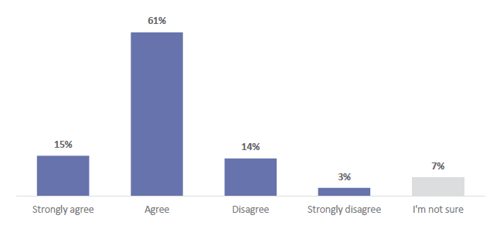

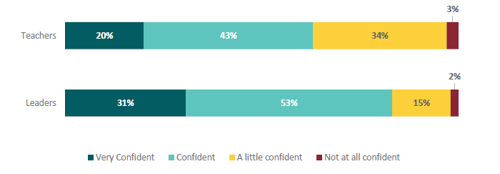

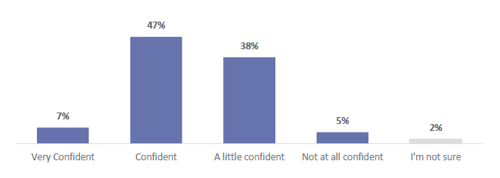

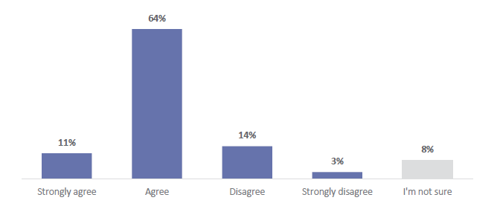

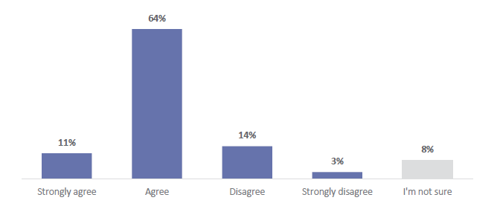

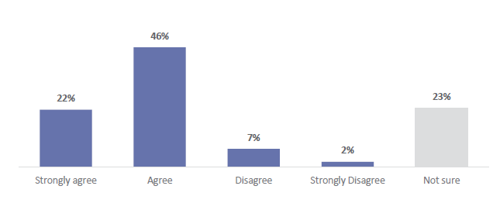

Finding 11: Three-quarters (75 percent) of leaders and teachers are confident in their understanding of the ANZ Histories content and nine in 10 teachers enjoy teaching it. We heard this is because teachers could make the learning more meaningful and relevant to their students.

Finding 12: However, some teachers are overwhelmed by the scale of changes. Teachers describe the challenge, firstly, of growing their local histories knowledge, and then sharing that knowledge with their students. Half of schools had limited or no engagement with local hapū or iwi on the curriculum. And some teachers do not feel safe teaching histories outside their culture, especially non-Māori teachers teaching Māori history.

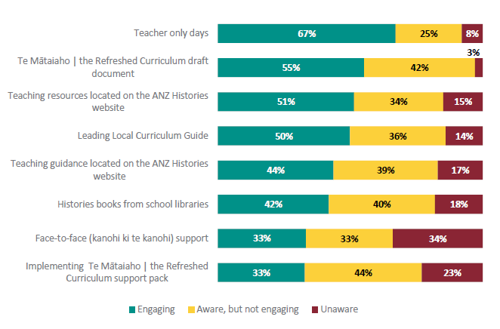

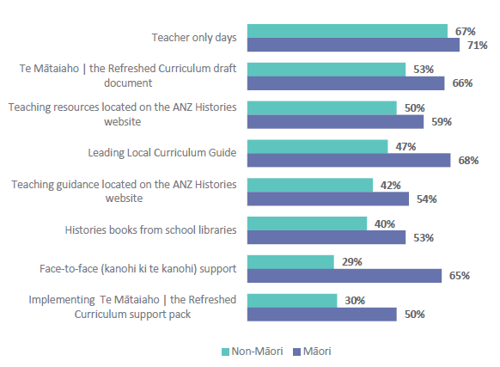

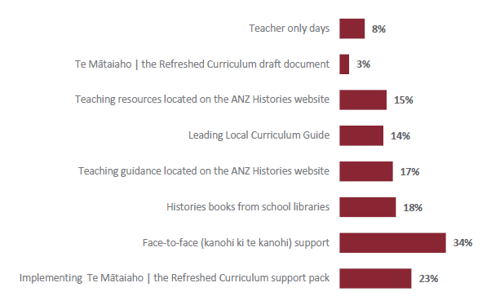

Finding 13: In introducing ANZ Histories, the support teachers have found most helpful are teacher only days, in-person support from Ministry of Education's regionally based Curriculum Leads, and collaboration with other schools.

Finding 14: Schools find developing a local curriculum challenging. They don’t understand what is required, they don’t have the skills to develop a curriculum, and it takes a lot of time to access resources.

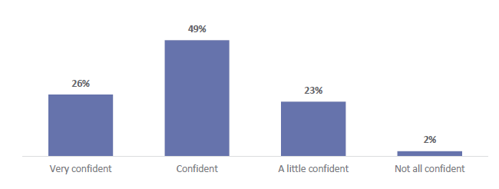

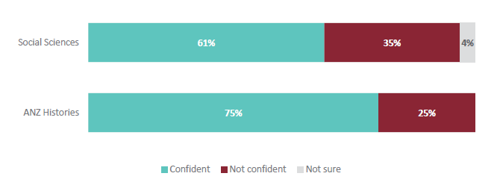

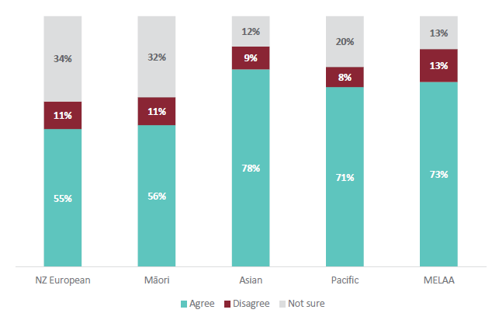

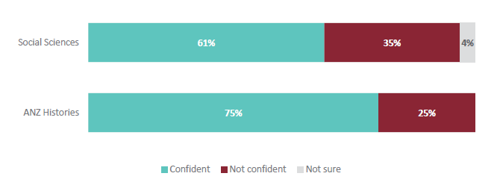

Finding 15: Leaders and teachers are less confident in their understanding of the refreshed Social Sciences compared to ANZ Histories. So far just six in 10 (61 percent) are confident or very confident. Only six in 10 leaders and teachers say they have been supported by the school leadership team to implement the changes for Social Sciences, compared to seven in 10 for ANZ Histories.

Area 4: Impact on parents and whānau

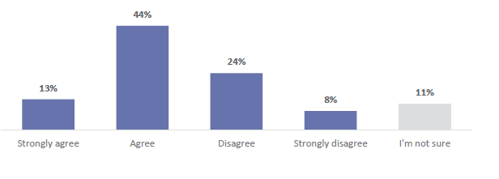

Parents and whānau want their children to learn ANZ Histories. They want more global context included and say how ANZ Histories is taught is as important as what is taught.

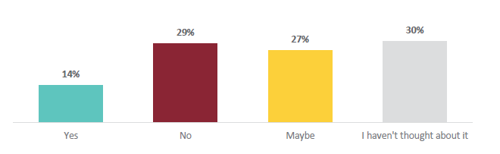

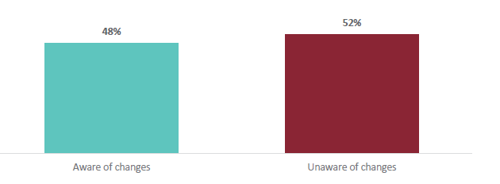

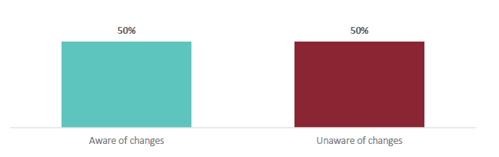

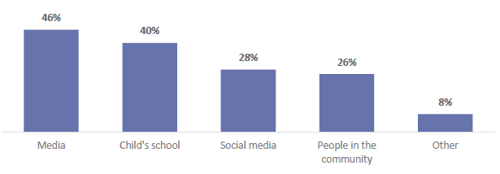

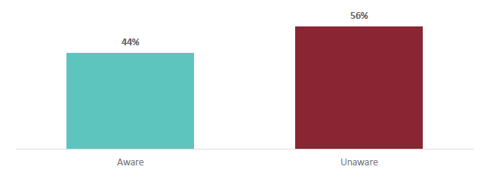

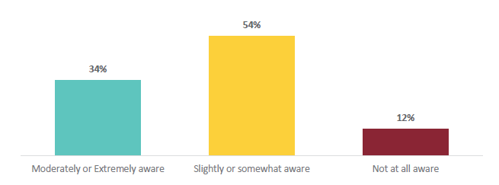

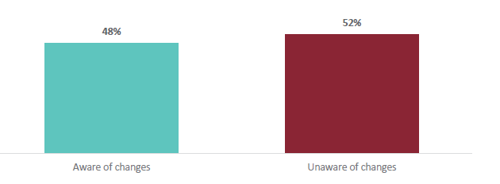

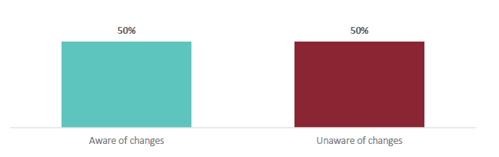

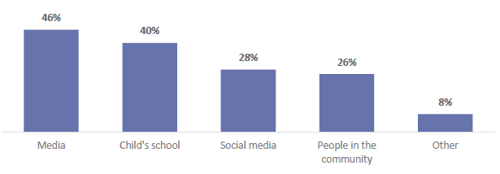

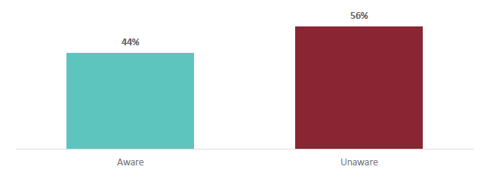

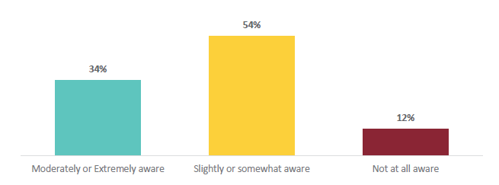

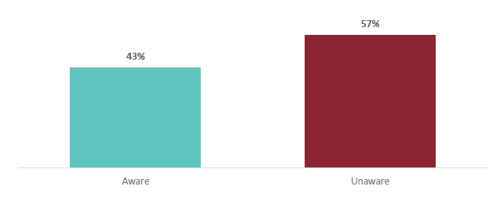

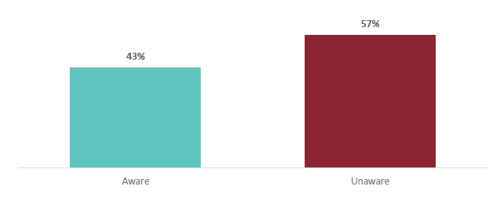

Finding 16: Many parents and whānau are unaware of the changes to the curriculum, and most have not been told about, nor involved in, the changes to ANZ Histories or the Social Sciences by their child’s school.

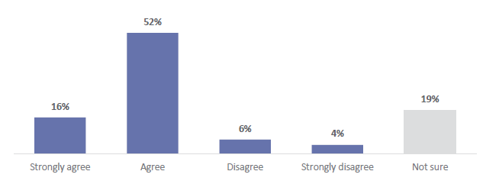

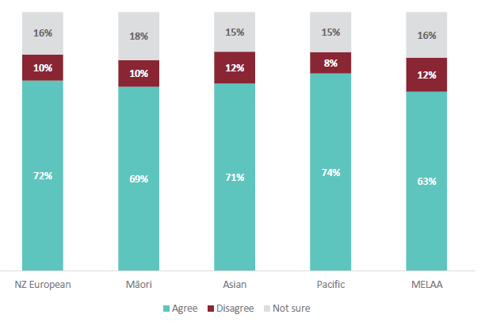

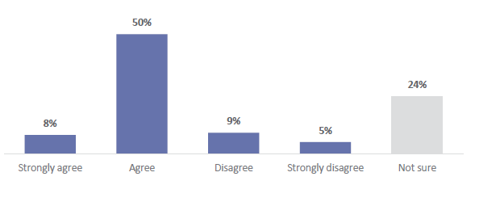

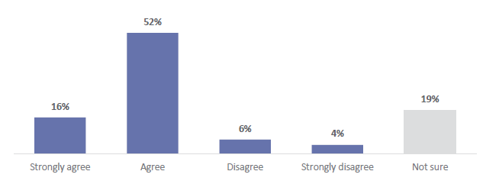

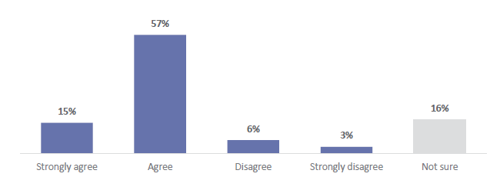

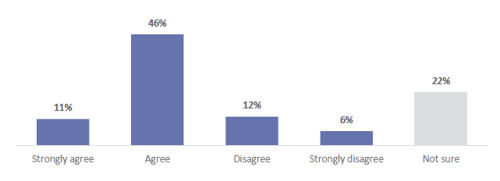

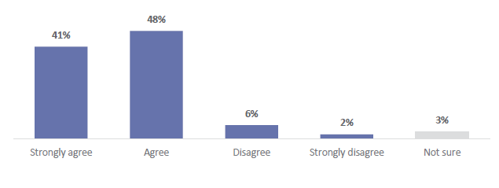

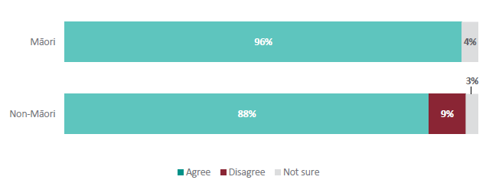

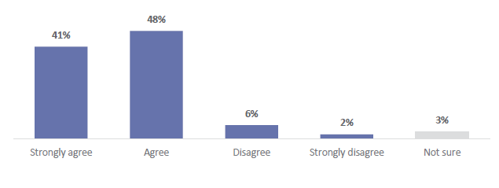

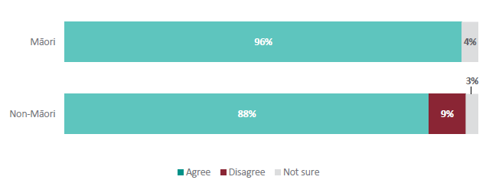

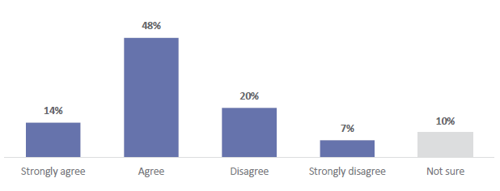

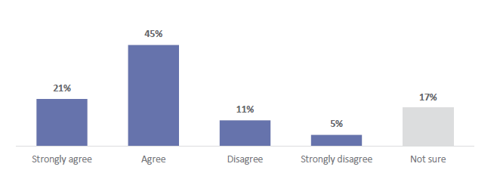

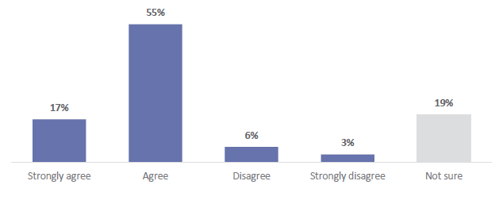

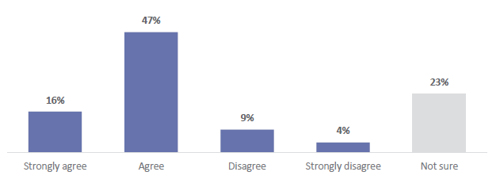

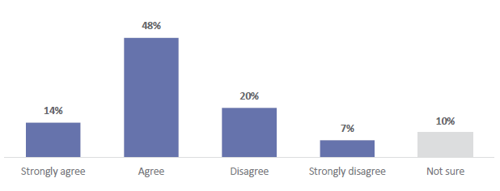

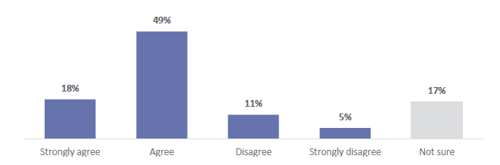

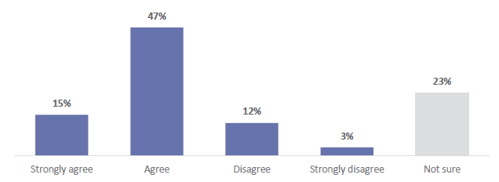

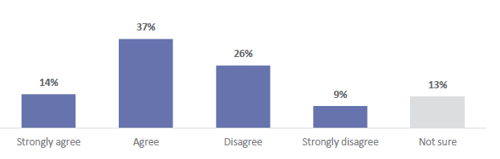

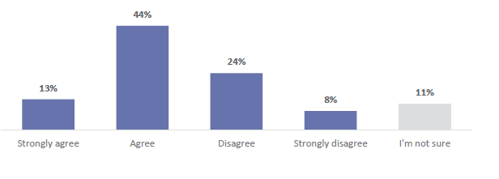

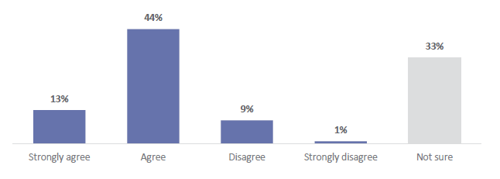

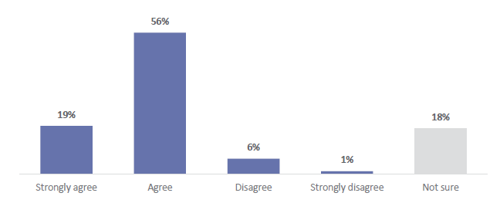

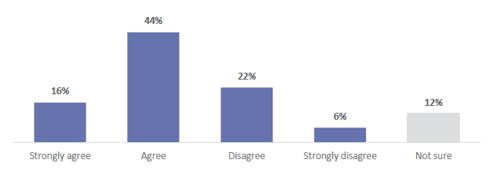

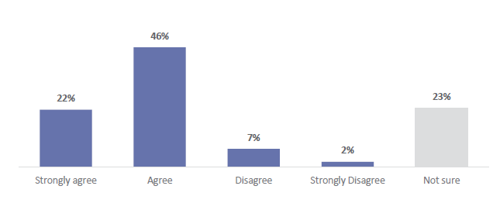

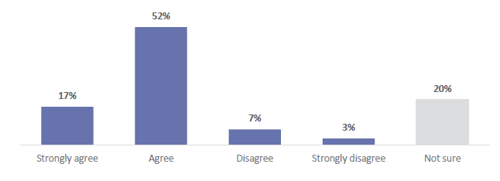

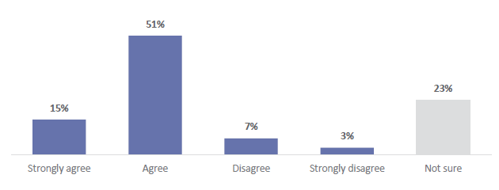

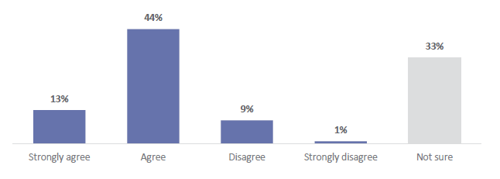

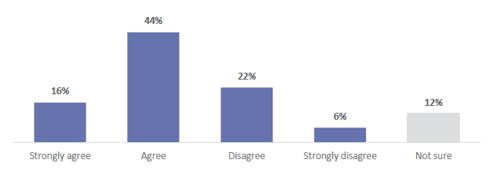

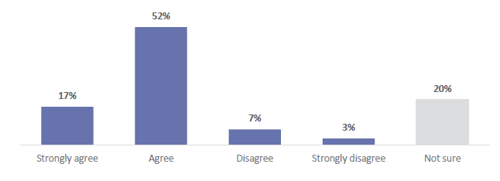

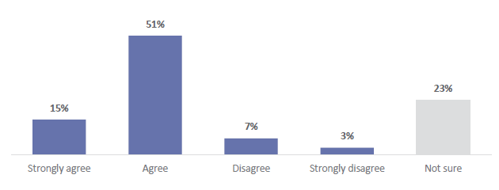

Finding 17: Two-thirds (66 percent) of parents and whānau think ANZ Histories is useful for their child’s future. Most parents and whānau we spoke to are pleased that ANZ Histories is being implemented in schools, expressing that learning about ANZ Histories fits their expectations for what school should offer.

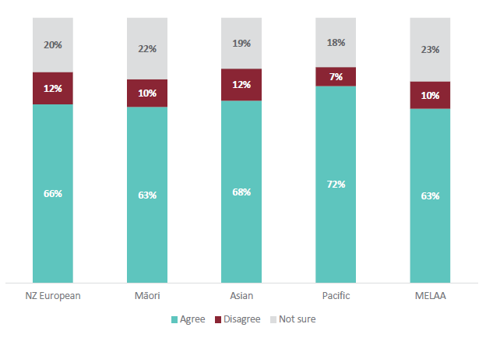

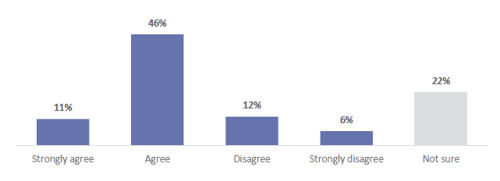

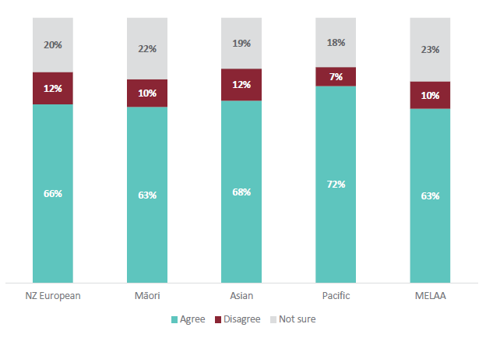

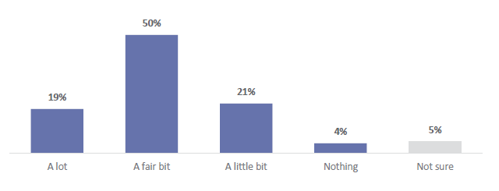

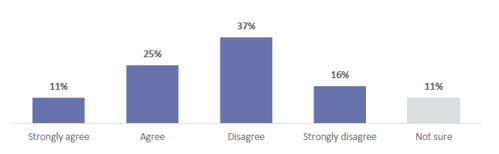

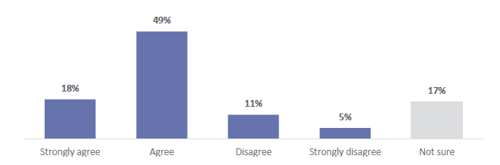

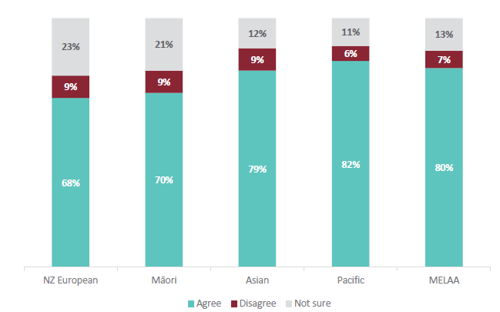

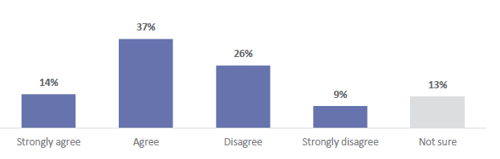

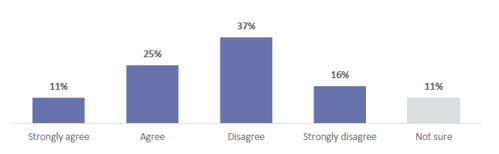

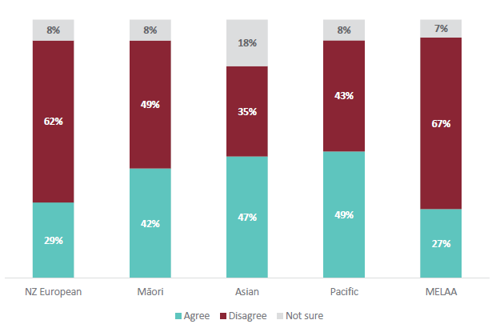

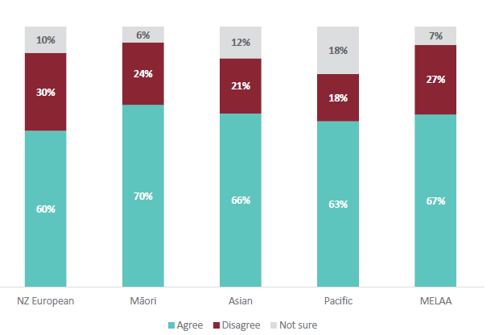

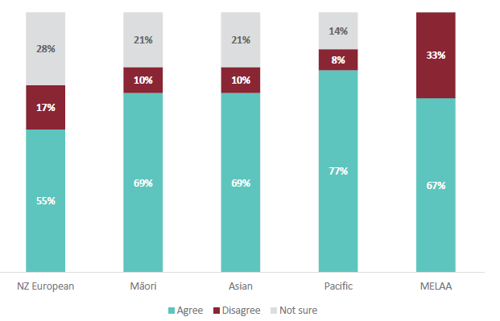

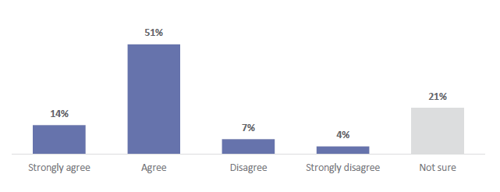

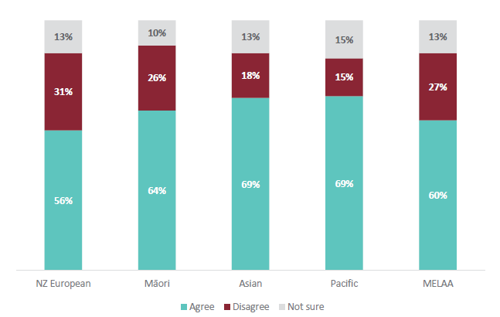

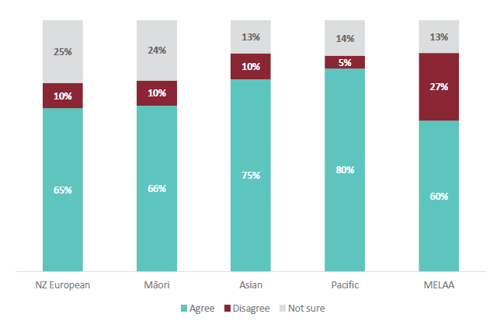

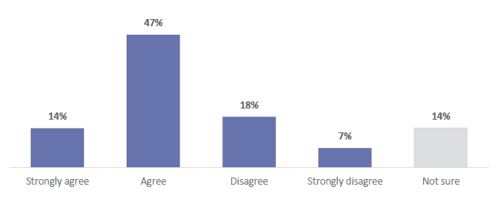

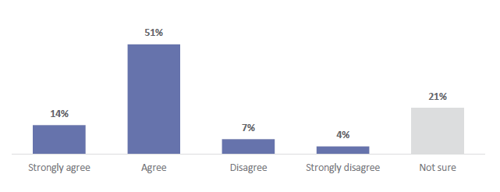

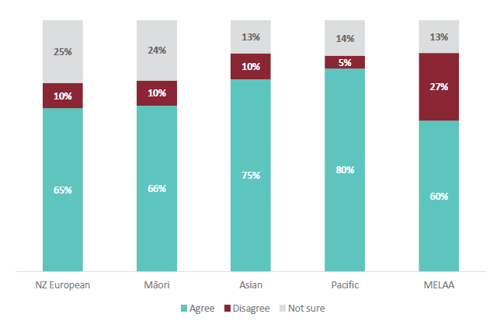

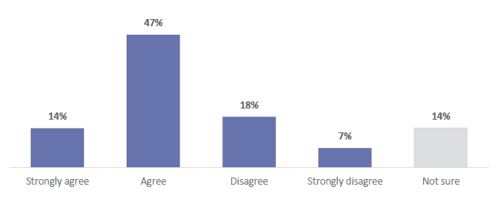

Finding 18: Only three in five (62 percent) parents and whānau think their child sees themselves represented in their learning for ANZ Histories. Some want the learning to include more national events and global histories, as their children are interested in global events and New Zealand should not be seen in a vacuum.

Finding 19: Parents and whānau think ‘how’ curriculum content is delivered is as, or more important, than the material itself. They say that histories can be contentious and need to be taught sensitively to avoid disengaging students.

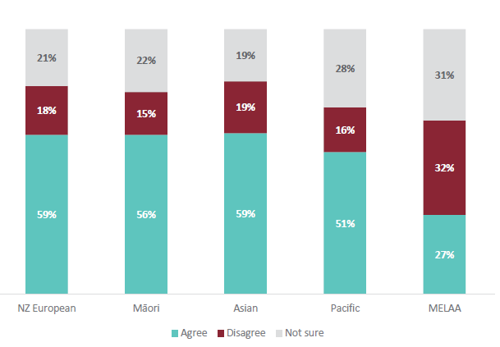

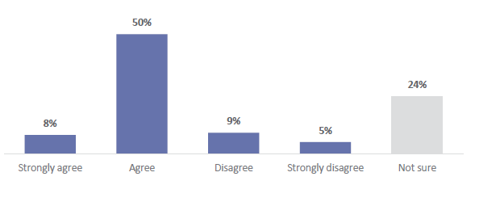

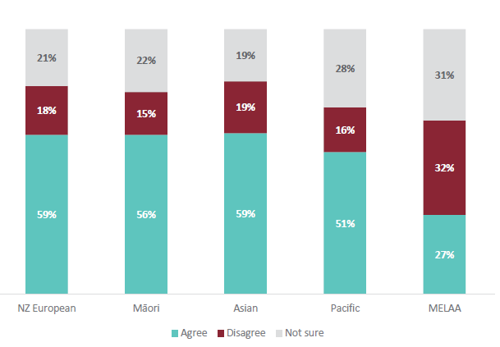

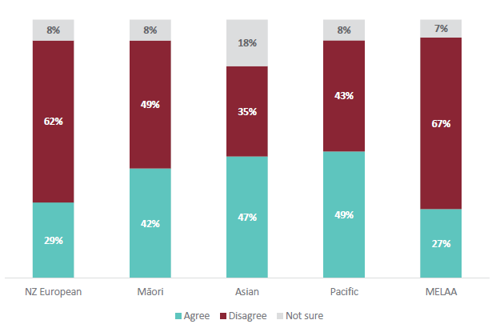

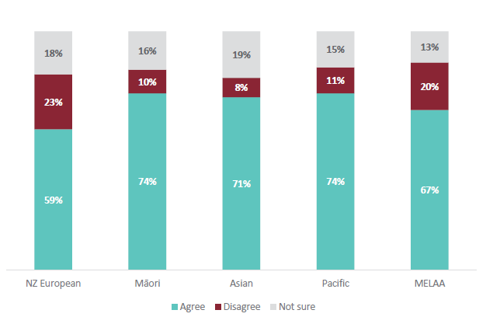

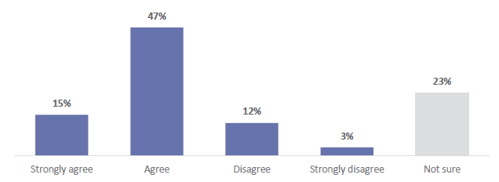

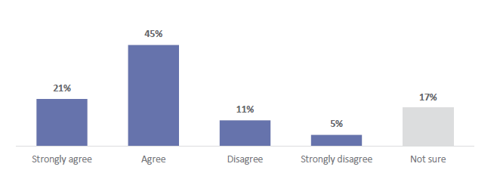

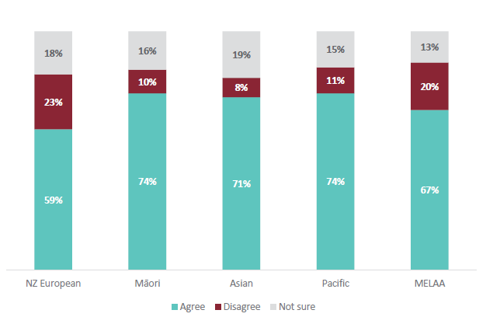

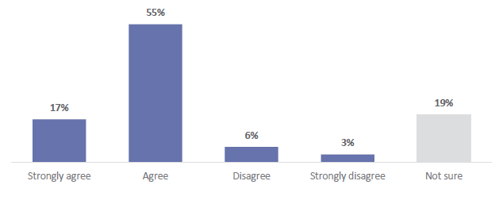

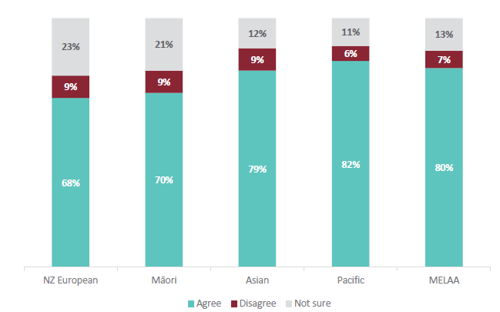

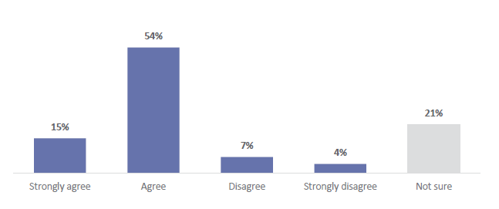

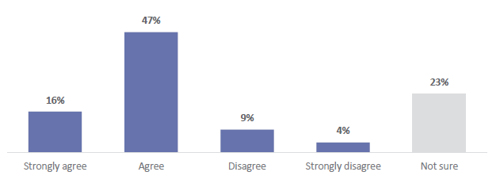

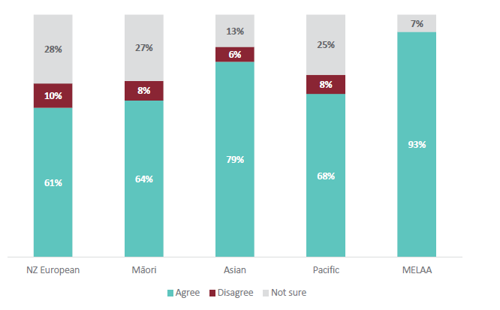

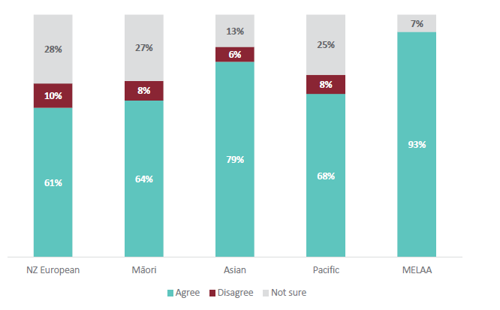

Finding 20: Similar to ANZ Histories, just over two-thirds (68 percent) of parents and whānau think the Social Sciences is useful for their child’s future, and three in five (61 percent) think their child sees themselves represented in their learning. Different to ANZ Histories, Asian and MELAA parents and whānau are most likely to say their child can see themselves in their learning for the Social Sciences. NZ European parents and whānau are the least likely to say their child can see themselves represented for both ANZ Histories and the Social Sciences.

Lessons learnt

Based on ERO’s key findings, seven lessons have been identified for ensuring balanced ANZ Histories curriculum content, and for supporting the successful implementation of curriculum changes in other learning areas:

Lesson 1: Keep making ANZ Histories engaging, by teaching about people, places, and events that students can relate to and history relevant to them and their communities.

Students are enjoying ANZ Histories. It has engaged a wide range of students, in particular Māori students. Teachers report positive impacts on student participation, and students (from all backgrounds) report learning in ANZ Histories helps them connect to ‘being a New Zealander’. Students, especially Māori and Pacific students, enjoy learning ANZ Histories, and teachers and parents and whānau see students are engaged in their learning. It is important that this engagement and enjoyment is not lost, as implementation continues.

Lesson 2: Provide clearer expectations about what needs to be covered to make sure all areas of ANZ Histories are taught, including the national and global context.

Teachers are often interpreting ANZ Histories as the history of their immediate area, and Māori history. This has led to a lack of focus on the history of Aotearoa New Zealand more broadly, and the histories of all people who call it home. Teachers would benefit from guidance around how much attention to give:

- Knowledge of history and the Social Science skills involved

- Māori history

- The histories of other people who call/have called New Zealand home

- The history of their immediate area

- The history of Aotearoa New Zealand more broadly

- Aotearoa New Zealand’s place in the world

- Global relationships and connections.

Lesson 3: Have a more explicit curriculum and provide more ‘can be used off the shelf’ content and exemplars.

Schools are struggling to develop their ANZ Histories content because their teachers are not experts in curriculum design. Developing a school curriculum is a big ask of schools and they would benefit from more explicit guidance around curriculum design, or a more prescriptive curriculum. Local hapū and iwi can support development of content but cannot alone support the framing of events from multiple perspectives.

Lesson 4: Be realistic about the capacity of both schools and hapū and iwi to engage on changes to the curriculum.

Schools are expected to engage with local hapū and iwi to develop their ANZ Histories curriculum content, but this often isn’t happening. Half of schools have limited or no engagement with local hapū and iwi on Social Sciences, including ANZ Histories. Some schools are facing challenges due to lack of capacity and capability to engage with hapū and iwi. We also heard from schools that hapū or iwi don’t have the capacity to work with all the schools in their area (rohe). Schools would benefit from ‘off the shelf’ teaching and learning resources about Māori histories to fill the gap, until schools are able to develop those relationships. Hapū and iwi would benefit from resourcing or support so they can provide schools with the help they need.

Lesson 5: Provide further guidance and tools for assessing student progress.

While teachers appreciate the clarity of the Phases of Learning (learning progressions), they are unsure how to measure and track how well students are learning and progressing in ANZ Histories, or Social Sciences more broadly. Teachers would benefit from greater guidance on measuring and tracking progress, as well as easy-to-use assessment tools that align with the Phases of Learning and the skills students are expected to develop.

Lesson 6: Keep providing supports and resources (including Curriculum Leads who work with schools), but make sure they are available to schools for the start of implementation and are well signposted.

The most useful and impactful supports for the implementation of ANZ Histories have been teacher only days, in-person support from Curriculum Leads, and collaboration with other schools that are part of a cluster, such as Kāhui Ako. It is important that these supports are in place – and accessible to all schools – for the roll out of new curriculum areas. The Ministry’s resources have also provided critical support for implementation, but teachers often don’t know when new supports are available or where to find them. Schools stand a better chance of accessing the curriculum resources they need if they are made available for the start of implementation, and are accessible from a single website that is well-publicized.

Lesson 7: Better, more targeted support, tailored for schools at the different stages of implementation.

We found that schools are at different stages of implementation. Each stage of implementation has different support needs. Therefore, schools would benefit from targeted support to help them towards fully embedding changes.

Conclusion

ERO found that ANZ Histories is being taught in all schools but, so far, not all year levels. Schools are prioritising local and Māori histories and teaching less about national and global contexts. Schools also have a stronger focus on teaching about culture and identity, and place and environment, than about government and organisation and economic activity and are prioritising ANZ Histories over the wider Social Sciences.

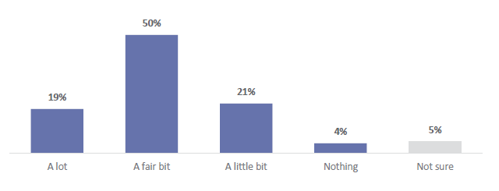

About half of students enjoy ANZ Histories. Student engagement is improved when students can see themselves in their learning, and are learning about people like them. Teachers like ANZ Histories and are mostly positive about making the changes, but are overwhelmed by the scale of change required. Half of parents and whānau are unaware of the changes to the curriculum, and even fewer have been involved. They are pleased that ANZ Histories is being implemented but want it to be taught sensitively.

Schools can be better supported by making the national curriculum more explicit and providing more ‘can be used off the shelf’ content. They also need supports and resources to be easily accessible, including clearer guidance and tools for assessing student progress.

In 2023, teaching Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories (ANZ Histories) became compulsory for students in Years 1-10. ANZ Histories is part of the refreshed Social Sciences learning area. The Education Review Office, in partnership with the Ministry of Education, wanted to know how the implementation of ANZ Histories and the wider Social Sciences is going.

This report describes what we found about the changes and the impacts for students, teachers, and parents and whānau. It also describes the lessons that can help inform the ongoing implementation of the Refreshed Curriculum.

What is Social Sciences and why is it important?

Social Sciences, sometimes referred to as Social Studies in primary schools, is the study of how societies work, both now, in the past and in the future. Social Sciences include subject areas like history, geography, economics, psychology, sociology, and media studies that students can specialise in, typically at senior secondary school. Students learn about:

- how societies work

- the past, present, and future

- people, places, cultures, histories, and the economic world within and beyond Aotearoa New Zealand.

In doing so, the Social Sciences helps students develop knowledge and skills to understand, participate in and contribute to local, national, and global communities.

What is Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories?

Learning about ANZ Histories builds understanding about how Māori and all people who have, or now, call Aotearoa New Zealand home, have shaped Aotearoa New Zealand’s past. Understanding the past helps students critically evaluate what is happening now, and what may happen in the future.

ANZ Histories content is intended to teach students to ‘understand’ big ideas about ANZ Histories, to ‘know’ the historical context, and to be able to ‘do’ practices such as thinking, evaluating, and communicating historical information.

What has changed in Social Sciences, including Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories?

Te Ao Tangata | the refreshed Social Sciences (Social Sciences) is the first learning area to be made available to schools as part of Te Mātaiaho | the Refreshed New Zealand Curriculum (the Refreshed Curriculum). Only ANZ Histories, which is a part of the refreshed Social Sciences, became compulsory for students in Years 1-10 from the beginning of 2023. Teaching the wider refreshed Social Sciences is not required until 2027.

As part of the Refreshed Curriculum, the Understand, Know, Do framework has been introduced to be clearer about the ‘learning that matters’ and to specify that learning needs to cover subject knowledge, as well as competencies and skills. Additionally, progress outcomes have replaced the previous achievement objectives.

What we looked at

ERO’s evaluation focused on the implementation of ANZ Histories within the refreshed Social Sciences learning area. We set out to answer the following questions:

- What is being taught for ANZ Histories?

- What has been the impact of ANZ Histories on students, teachers, and communities?

- What has been working well and less well in making the changes to include ANZ Histories?

- What is being taught for the refreshed Social Sciences learning area more broadly, and what impact is it having?

- What are the lessons for ANZ Histories and for implementing other curriculum areas?

Where we looked

We have taken a robust, mixed-methods approach to deliver breadth and depth, including:

- site visits at 11 schools

- surveys of 447 school leaders and teachers

- surveys of 918 students

- surveys of 1,016 parents and whānau

- in-depth interviews with school leaders, teachers, students, parents and whānau, experts in curriculum and/or relevant subject matter, and one kaumatua of a hapū.

We collected our data in late Term 3 and early Term 4 of 2023.

Key Findings

ERO identified key findings across four areas:

- what is being taught

- impact on students

- impact for teachers

- impact on parents and whānau.

Our findings focus on ANZ Histories because this is required to be taught and is where most of the change is happening. We found limited change for the wider refreshed Social Sciences.

Area 1: What is being taught?

It has been compulsory for less than a year and not all year levels are yet being taught ANZ Histories, and not all of the content is being taught. Schools are prioritising local and Māori histories and teaching ANZ Histories over Social Sciences.

Finding 1: ANZ Histories became compulsory at the start of 2023. Three-quarters of schools are teaching it at all year levels. Primary schools are more likely to be teaching it. Schools are prioritising implementing ANZ Histories, to avoid overwhelming teachers, and this is crowding out other areas of Social Sciences.

Finding 2: Of the four ‘Understands’ (big ideas), schools are prioritising teaching Māori history (64 percent teaching this) and colonisation (61 percent) more than relationships across boundaries and people (53 percent), and the use of power (41 percent). In terms of the ‘Know’ (contexts), schools have had a much stronger focus on teaching about culture and identity (77 percent), and place and environment (71 percent) than about government and organisation (45 percent) and economic activity (30 percent).

Finding 3: The curriculum statements are being interpreted by schools so that they are focusing on local histories rather than national events, and local is sometimes interpreted as only Māori histories. Schools are also teaching less about global contexts.

Finding 4: Teachers need to weave Understand, Know, and Do together but are not yet able to do that and are mainly focusing on the Know. Both primary and secondary schools told us that the Do inquiry practices are not yet a focus in their teaching of ANZ Histories. This matters because the inquiry practices help students to be critical thinkers.

Area 2: Impact on students

Half of students enjoy learning about ANZ Histories. Students enjoy ANZ Histories more when it includes global contexts and when they are learning about people similar to them. The focus on Māori and Pacific history means Māori and Pacific students are enjoying ANZ Histories more than NZ European, Asian, and MELAA students.

Finding 5: Teaching ANZ Histories has been compulsory for less than a year. At this stage, just over half of students enjoy learning about ANZ Histories. Two-thirds of teachers have seen positive impacts on student participation.

Finding 6: It’s important to retain a link to global contexts and events. Students are more than twice as likely to enjoy ANZ Histories when they are learning about New Zealand’s place in the world.

Finding 7: Students are twice as likely to enjoy ANZ Histories when their learning is connecting them to their whānau and community, and when they are learning about people similar to them. Half of Māori and Pacific students (51 percent) report learning about people similar to them in ANZ Histories, but only two-fifths of Asian (43 percent) and NZ European (39 percent) students, and only a quarter (23 percent) of MELAA students do.

Finding 8: Enjoyment of learning ANZ Histories is not the same for all ethnicities. While almost two-thirds of Pacific students enjoy ANZ Histories (63 percent) and the majority of Māori students are also enjoying it (61 percent), fewer Asian students (55 percent), only half of NZ European students (50 percent), and less than half of MELAA students (42 percent) enjoy it.

Finding 9: It is too early to measure the progress students are making in their learning in ANZ Histories. But nearly two in five students either aren’t sure or don’t think they are making progress in ANZ Histories. Some teachers are unclear on how to track progress.

Finding 10: Similar to ANZ Histories, more than half of students enjoy learning (56 percent) and like to participate (57 percent) in learning about Social Sciences. Asian and NZ European students are enjoying Social Sciences the most, and MELAA and Māori students the least, which is different to ANZ Histories.

Area 3: Impact on school leaders and teachers

Teachers like teaching ANZ Histories, but some are overwhelmed by the scale of change and they don’t have the skills or time needed to develop a local curriculum.

Finding 11: Three-quarters (75 percent) of leaders and teachers are confident in their understanding of the ANZ Histories content and nine in 10 teachers enjoy teaching it. We heard this is because teachers could make the learning more meaningful and relevant to their students.

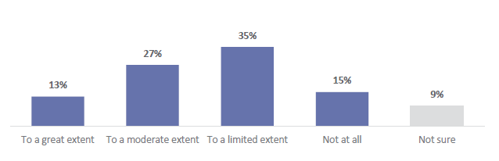

Finding 12: However, some teachers are overwhelmed by the scale of changes. Teachers describe the challenge, firstly, of growing their local histories knowledge, and then sharing that knowledge with their students. Half of schools had limited or no engagement with local hapū or iwi on the curriculum. And some teachers do not feel safe teaching histories outside their culture, especially non-Māori teachers teaching Māori history.

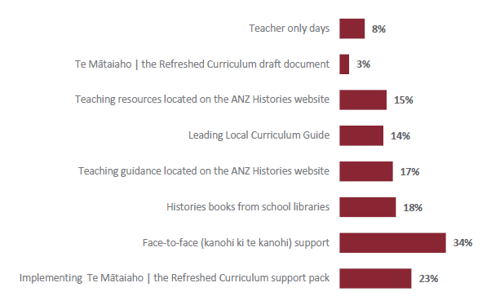

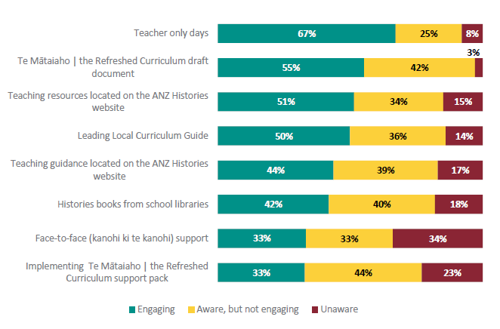

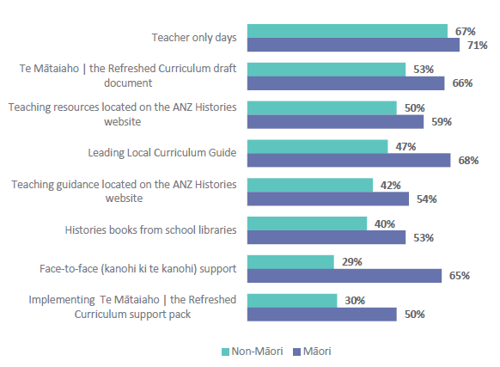

Finding 13: In introducing ANZ Histories, the support teachers have found most helpful are teacher only days, in-person support from Ministry of Education's regionally based Curriculum Leads, and collaboration with other schools.

Finding 14: Schools find developing a local curriculum challenging. They don’t understand what is required, they don’t have the skills to develop a curriculum, and it takes a lot of time to access resources.

Finding 15: Leaders and teachers are less confident in their understanding of the refreshed Social Sciences compared to ANZ Histories. So far just six in 10 (61 percent) are confident or very confident. Only six in 10 leaders and teachers say they have been supported by the school leadership team to implement the changes for Social Sciences, compared to seven in 10 for ANZ Histories.

Area 4: Impact on parents and whānau

Parents and whānau want their children to learn ANZ Histories. They want more global context included and say how ANZ Histories is taught is as important as what is taught.

Finding 16: Many parents and whānau are unaware of the changes to the curriculum, and most have not been told about, nor involved in, the changes to ANZ Histories or the Social Sciences by their child’s school.

Finding 17: Two-thirds (66 percent) of parents and whānau think ANZ Histories is useful for their child’s future. Most parents and whānau we spoke to are pleased that ANZ Histories is being implemented in schools, expressing that learning about ANZ Histories fits their expectations for what school should offer.

Finding 18: Only three in five (62 percent) parents and whānau think their child sees themselves represented in their learning for ANZ Histories. Some want the learning to include more national events and global histories, as their children are interested in global events and New Zealand should not be seen in a vacuum.

Finding 19: Parents and whānau think ‘how’ curriculum content is delivered is as, or more important, than the material itself. They say that histories can be contentious and need to be taught sensitively to avoid disengaging students.

Finding 20: Similar to ANZ Histories, just over two-thirds (68 percent) of parents and whānau think the Social Sciences is useful for their child’s future, and three in five (61 percent) think their child sees themselves represented in their learning. Different to ANZ Histories, Asian and MELAA parents and whānau are most likely to say their child can see themselves in their learning for the Social Sciences. NZ European parents and whānau are the least likely to say their child can see themselves represented for both ANZ Histories and the Social Sciences.

Lessons learnt

Based on ERO’s key findings, seven lessons have been identified for ensuring balanced ANZ Histories curriculum content, and for supporting the successful implementation of curriculum changes in other learning areas:

Lesson 1: Keep making ANZ Histories engaging, by teaching about people, places, and events that students can relate to and history relevant to them and their communities.

Students are enjoying ANZ Histories. It has engaged a wide range of students, in particular Māori students. Teachers report positive impacts on student participation, and students (from all backgrounds) report learning in ANZ Histories helps them connect to ‘being a New Zealander’. Students, especially Māori and Pacific students, enjoy learning ANZ Histories, and teachers and parents and whānau see students are engaged in their learning. It is important that this engagement and enjoyment is not lost, as implementation continues.

Lesson 2: Provide clearer expectations about what needs to be covered to make sure all areas of ANZ Histories are taught, including the national and global context.

Teachers are often interpreting ANZ Histories as the history of their immediate area, and Māori history. This has led to a lack of focus on the history of Aotearoa New Zealand more broadly, and the histories of all people who call it home. Teachers would benefit from guidance around how much attention to give:

- Knowledge of history and the Social Science skills involved

- Māori history

- The histories of other people who call/have called New Zealand home

- The history of their immediate area

- The history of Aotearoa New Zealand more broadly

- Aotearoa New Zealand’s place in the world

- Global relationships and connections.

Lesson 3: Have a more explicit curriculum and provide more ‘can be used off the shelf’ content and exemplars.

Schools are struggling to develop their ANZ Histories content because their teachers are not experts in curriculum design. Developing a school curriculum is a big ask of schools and they would benefit from more explicit guidance around curriculum design, or a more prescriptive curriculum. Local hapū and iwi can support development of content but cannot alone support the framing of events from multiple perspectives.

Lesson 4: Be realistic about the capacity of both schools and hapū and iwi to engage on changes to the curriculum.

Schools are expected to engage with local hapū and iwi to develop their ANZ Histories curriculum content, but this often isn’t happening. Half of schools have limited or no engagement with local hapū and iwi on Social Sciences, including ANZ Histories. Some schools are facing challenges due to lack of capacity and capability to engage with hapū and iwi. We also heard from schools that hapū or iwi don’t have the capacity to work with all the schools in their area (rohe). Schools would benefit from ‘off the shelf’ teaching and learning resources about Māori histories to fill the gap, until schools are able to develop those relationships. Hapū and iwi would benefit from resourcing or support so they can provide schools with the help they need.

Lesson 5: Provide further guidance and tools for assessing student progress.

While teachers appreciate the clarity of the Phases of Learning (learning progressions), they are unsure how to measure and track how well students are learning and progressing in ANZ Histories, or Social Sciences more broadly. Teachers would benefit from greater guidance on measuring and tracking progress, as well as easy-to-use assessment tools that align with the Phases of Learning and the skills students are expected to develop.

Lesson 6: Keep providing supports and resources (including Curriculum Leads who work with schools), but make sure they are available to schools for the start of implementation and are well signposted.

The most useful and impactful supports for the implementation of ANZ Histories have been teacher only days, in-person support from Curriculum Leads, and collaboration with other schools that are part of a cluster, such as Kāhui Ako. It is important that these supports are in place – and accessible to all schools – for the roll out of new curriculum areas. The Ministry’s resources have also provided critical support for implementation, but teachers often don’t know when new supports are available or where to find them. Schools stand a better chance of accessing the curriculum resources they need if they are made available for the start of implementation, and are accessible from a single website that is well-publicized.

Lesson 7: Better, more targeted support, tailored for schools at the different stages of implementation.

We found that schools are at different stages of implementation. Each stage of implementation has different support needs. Therefore, schools would benefit from targeted support to help them towards fully embedding changes.

Conclusion

ERO found that ANZ Histories is being taught in all schools but, so far, not all year levels. Schools are prioritising local and Māori histories and teaching less about national and global contexts. Schools also have a stronger focus on teaching about culture and identity, and place and environment, than about government and organisation and economic activity and are prioritising ANZ Histories over the wider Social Sciences.

About half of students enjoy ANZ Histories. Student engagement is improved when students can see themselves in their learning, and are learning about people like them. Teachers like ANZ Histories and are mostly positive about making the changes, but are overwhelmed by the scale of change required. Half of parents and whānau are unaware of the changes to the curriculum, and even fewer have been involved. They are pleased that ANZ Histories is being implemented but want it to be taught sensitively.

Schools can be better supported by making the national curriculum more explicit and providing more ‘can be used off the shelf’ content. They also need supports and resources to be easily accessible, including clearer guidance and tools for assessing student progress.

About this report

In 2023, Aotearoa New Zealand began a refresh of the national curriculum starting with Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories (ANZ Histories), which must be taught to all students in Years 1 – 10. ANZ Histories is part of the refreshed Social Sciences learning area, although teaching the other refreshed parts is not required until 2027.

The Education Review Office, in partnership with the Ministry of Education (the Ministry), wanted to know how the implementation is going. This report describes what we found about the changes to teaching and the impacts for students, teachers, and communities. It also describes the lessons that can inform and support the ongoing implementation of the Refreshed Curriculum.

What is Social Sciences and why is it important?

Social Sciences, sometimes referred to as Social Studies in primary schools, is the study of how societies work, both now, in the past and in the future.

Included in the Social Sciences learning area are subject areas like history, geography, economics, psychology, sociology, and media studies that students can specialise in, typically at senior secondary school. Students learn about:

- how societies work

- the past, present, and future

- people, places, cultures, histories, and the economic world within and beyond Aotearoa New Zealand.

Social Sciences helps students develop the knowledge and skills to understand, participate in and contribute to local, national, and global communities.

It is important that students learn about how to think through social issues, how to evaluate information, and how to come to a view on the social, economic, political, and environmental issues that will shape their future. Students who have these skills can fully participate in society. They also set themselves up for a multitude of careers including working as economists, policymakers, planners, social workers, psychologists, and politicians.

What is ANZ Histories?

Understanding Aotearoa New Zealand’s past helps students critically evaluate what is happening now, and what may happen in the future.

The ANZ Histories content is intended to build understanding about how Māori and all people who have, or now, call Aotearoa New Zealand home, and have shaped Aotearoa New Zealand’s past. Students learn to ‘understand’ big ideas about ANZ Histories, to ‘know’ the contexts, and to be able to ‘do’ practices such as thinking, evaluating, and communicating historical information. Figure 2 describes the key elements of ANZ Histories using the Understand, Know, Do framework.

Understand, Know, Do for Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories (ANZ Histories)Understand – the big ideas1. Māori history is the foundational and continuous history of Aotearoa New Zealand 2. Colonisation and settlement have been central to Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories for the past 200 years 3. The course of Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories has been shaped by the use of power 4. Relationships and connections between people and across boundaries have shaped the course of Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories Know – the contexts1. Culture and identity 2. Government and organisation 3. Place and environment 4. Economic activity Do – inquiry practices1. Identifying and exploring historical relationships 2. Identifying sources and perspectives 3. Interpreting past experiences, decisions, and actions |

What has changed in Social Sciences, including ANZ Histories?

There used to be a lot of flexibility about what exactly was taught, and how.

The 2007 NZ Curriculum allowed for the teaching of Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories as part of the Social Sciences learning area, but it was not explicit that New Zealand’s histories had to be taught. This changed with the addition of ANZ Histories content followed by the refreshed Social Sciences learning area in Te Mātaiaho | the Refreshed New Zealand Curriculum (the Refreshed Curriculum).

The addition of ANZ Histories content has given more specificity about what should be taught about local and national histories as part of the Social Sciences learning area.

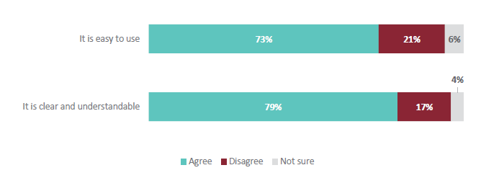

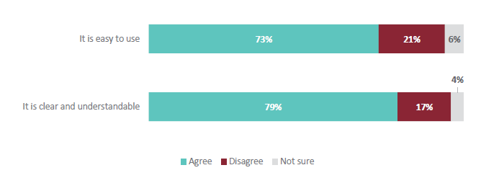

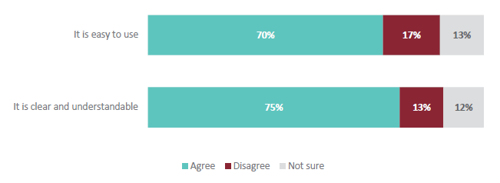

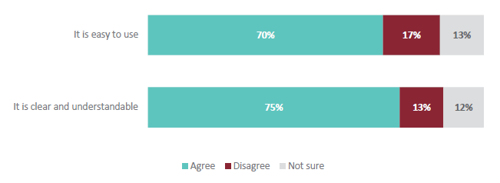

Te Ao Tangata | the refreshed Social Sciences learning area (Social Sciences), including ANZ Histories, is part of a broader refresh of the national curriculum. The Refreshed Curriculum aims to be:

- inclusive

- clear about the learning that matters

- easy to use

- give practical effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi | the Treaty of Waitangi.(1)

The Refreshed Curriculum aims to address concerns, across all learning areas, that the 2007 NZ Curriculum:

- prioritised competencies and skills too much over subject knowledge – a lack of subject knowledge in the curriculum is also associated with poorer student achievement according to international evidence (2) and research in Aotearoa New Zealand(3)

- lacked sufficient detail, which meant students were frequently missing out on learning

that is important to them and their communities, leading to persistent inequalities in student achievement.(4)

The Understand, Know, Do framework, introduced as part of the Refreshed Curriculum, provides clearer guidance on the ‘learning that matters’ by specifying what students are expected to Understand (the big ideas), Know (the contexts), and Do (the inquiry practices). (5) The framework also specifies the need to cover subject knowledge as well as competencies and skills.

There are changes to how schools assess student progress and achievement.

The refreshed Social Sciences breaks expected learning up into five phases of learning, compared to the eight curriculum levels described in the 2007 NZ Curriculum. Teachers can access guidance and resources related to each of these phases.

Progress outcomes have replaced the previous achievement objectives. The progress outcomes specify what students should know and be able to do by the end of each phase of learning.

Schools are expected to use the Refreshed Curriculum to develop their own school curriculum.

While there is more specificity in the Refreshed Curriculum, schools are still expected to localise it. The Refreshed Curriculum identifies the learning that mattersuse this to design their school curriculum and develop content that can be taught to students in their classrooms. Each school curriculum will be unique. This flexibility is intended to enable schools to:

- be responsive to the needs, identity, language, culture, interests, strengths, and aspirations of their learners and their families

- have a clear focus on what supports the progress of all learners

- integrate Te Tiriti o Waitangi into classroom learning

- help learners engage with the knowledge, values, and competencies, so they can go on and be confident and connected lifelong learners.(6)

To develop their school curriculum for ANZ Histories, schools are encouraged to work with local whānau, hapū, and iwi.

Schools are expected to be working with their local communities, including hapū and iwi. For the implementation of ANZ Histories, schools are specifically guided to build productive and enduring partnerships with local whānau, hapū, and iwi, to understand and plan for the changes to their school curriculum content for ANZ Histories, especially for the ‘big idea’ - ‘Māori history is the foundational and continuous history of Aotearoa New Zealand.’(7)

The Ministry has provided a range of resources, supports, and professional learning opportunities to help schools localise and teach the ANZ Histories content.

Key supports include teaching resources available online(8) and regionally allocated professional learning and development about ANZ Histories. Schools can also ask for support from the Ministry’s Curriculum Leads, who can provide support to understand the national curriculum and to design quality and inclusive learning experiences for students.

What we looked at

ERO is working in partnership with the Ministry of Education (the Ministry) to evaluate the implementation of the Refreshed Curriculum. This is phase one of a multi-year evaluation that will provide real-time insights to inform and adjust the curriculum refresh as it is happening. The lessons can be used to inform implementation of the future curriculum changes.

We started with the evaluation of the Social Sciences learning area, including ANZ Histories, because this is the first learning area to be refreshed. We set out to answer the following questions.

- What is being taught for ANZ Histories?

- What has been the impact of ANZ Histories on students, teachers, and communities?

- What has been working well and less well in making the changes to include ANZ Histories?

- What is being taught for the refreshed Social Sciences learning area more broadly, and what impact is it having?

- What are the lessons for ANZ Histories and for implementing other curriculum areas?

This report focuses mainly on ANZ Histories because this is the only part of the refreshed Social Sciences learning area that is compulsory so far and is where most of the change is happening.

Where we looked

We engaged with curriculum leaders and teachers in primary and secondary schools who have responsibility for delivering Social Sciences content. In some schools, the curriculum leaders are principals or deputy principals. Throughout the report, we simply refer to ‘leaders.’

We focused on students in Years 4-10, and parents and whānau of students in Years 1-10.

We also spoke with a range of experts, including experts in curriculum design and people with other relevant subject matter expertise. We also spoke to a kaumatua of a hapū about their work with a local school to develop and implement ANZ Histories.

We have taken a robust, mixed-methods approach to deliver breadth and depth, including:

- site visits at 11 schools

- surveys of 447 school leaders and teachers

- surveys of 918 students

- surveys of 1016 parents and whānau

- interviews with 37 school leaders and 52 teachers

- interviews with 96 students

- interviews with 22 parents and whānau

- interviews with six experts in curriculum and/or relevant subject matter

- interview with one hapū representative.

We collected the data in late Term 3 and early Term 4 of 2023, when schools were meant to have been teaching ANZ histories to all students in Years 1 to 10 for at least two terms.

More details about our methodology are in Appendix 1.

Report structure

This report is divided into seven parts.

Part 1 describes what is happening in schools following the requirement to teach ANZ Histories and the availability of the Refreshed Curriculum content for the wider Social Sciences.

Part 2 looks at the impact for students so far, of learning ANZ Histories, focusing on how engaged and included they are and what progress they are making.

Part 3 looks at the impact for school leaders and teachers, focusing on their understanding of the ANZ Histories content, their confidence to teach it, their enjoyment of teaching it, and their capacity to implement the changes required.

Part 4 looks at the impact for parents and whānau, focusing on what they know about the curriculum changes, whether they are involved with the changes through their child’s school, what they think is important about ANZ Histories, and what impacts they are seeing so far.

Part 5 looks at the impact of the wider refreshed Social Sciences learning area, as far as is possible at this stage of the implementation.

Part 6 looks at what has worked and hasn’t worked in the implementation, so far, of ANZ Histories and the wider refreshed Social Sciences, with a focus on teacher capability and confidence, resources and supports, partnerships, and ways of working.

Part 7 sets out our key findings and lessons for the ongoing implementation of ANZ Histories, the wider refreshed Social Sciences, and other learning areas being updated as part of the curriculum refresh.

In 2023, Aotearoa New Zealand began a refresh of the national curriculum starting with Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories (ANZ Histories), which must be taught to all students in Years 1 – 10. ANZ Histories is part of the refreshed Social Sciences learning area, although teaching the other refreshed parts is not required until 2027.

The Education Review Office, in partnership with the Ministry of Education (the Ministry), wanted to know how the implementation is going. This report describes what we found about the changes to teaching and the impacts for students, teachers, and communities. It also describes the lessons that can inform and support the ongoing implementation of the Refreshed Curriculum.

What is Social Sciences and why is it important?

Social Sciences, sometimes referred to as Social Studies in primary schools, is the study of how societies work, both now, in the past and in the future.

Included in the Social Sciences learning area are subject areas like history, geography, economics, psychology, sociology, and media studies that students can specialise in, typically at senior secondary school. Students learn about:

- how societies work

- the past, present, and future

- people, places, cultures, histories, and the economic world within and beyond Aotearoa New Zealand.

Social Sciences helps students develop the knowledge and skills to understand, participate in and contribute to local, national, and global communities.

It is important that students learn about how to think through social issues, how to evaluate information, and how to come to a view on the social, economic, political, and environmental issues that will shape their future. Students who have these skills can fully participate in society. They also set themselves up for a multitude of careers including working as economists, policymakers, planners, social workers, psychologists, and politicians.

What is ANZ Histories?

Understanding Aotearoa New Zealand’s past helps students critically evaluate what is happening now, and what may happen in the future.

The ANZ Histories content is intended to build understanding about how Māori and all people who have, or now, call Aotearoa New Zealand home, and have shaped Aotearoa New Zealand’s past. Students learn to ‘understand’ big ideas about ANZ Histories, to ‘know’ the contexts, and to be able to ‘do’ practices such as thinking, evaluating, and communicating historical information. Figure 2 describes the key elements of ANZ Histories using the Understand, Know, Do framework.

Understand, Know, Do for Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories (ANZ Histories)Understand – the big ideas1. Māori history is the foundational and continuous history of Aotearoa New Zealand 2. Colonisation and settlement have been central to Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories for the past 200 years 3. The course of Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories has been shaped by the use of power 4. Relationships and connections between people and across boundaries have shaped the course of Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories Know – the contexts1. Culture and identity 2. Government and organisation 3. Place and environment 4. Economic activity Do – inquiry practices1. Identifying and exploring historical relationships 2. Identifying sources and perspectives 3. Interpreting past experiences, decisions, and actions |

What has changed in Social Sciences, including ANZ Histories?

There used to be a lot of flexibility about what exactly was taught, and how.

The 2007 NZ Curriculum allowed for the teaching of Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories as part of the Social Sciences learning area, but it was not explicit that New Zealand’s histories had to be taught. This changed with the addition of ANZ Histories content followed by the refreshed Social Sciences learning area in Te Mātaiaho | the Refreshed New Zealand Curriculum (the Refreshed Curriculum).

The addition of ANZ Histories content has given more specificity about what should be taught about local and national histories as part of the Social Sciences learning area.

Te Ao Tangata | the refreshed Social Sciences learning area (Social Sciences), including ANZ Histories, is part of a broader refresh of the national curriculum. The Refreshed Curriculum aims to be:

- inclusive

- clear about the learning that matters

- easy to use

- give practical effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi | the Treaty of Waitangi.(1)

The Refreshed Curriculum aims to address concerns, across all learning areas, that the 2007 NZ Curriculum:

- prioritised competencies and skills too much over subject knowledge – a lack of subject knowledge in the curriculum is also associated with poorer student achievement according to international evidence (2) and research in Aotearoa New Zealand(3)

- lacked sufficient detail, which meant students were frequently missing out on learning

that is important to them and their communities, leading to persistent inequalities in student achievement.(4)

The Understand, Know, Do framework, introduced as part of the Refreshed Curriculum, provides clearer guidance on the ‘learning that matters’ by specifying what students are expected to Understand (the big ideas), Know (the contexts), and Do (the inquiry practices). (5) The framework also specifies the need to cover subject knowledge as well as competencies and skills.

There are changes to how schools assess student progress and achievement.

The refreshed Social Sciences breaks expected learning up into five phases of learning, compared to the eight curriculum levels described in the 2007 NZ Curriculum. Teachers can access guidance and resources related to each of these phases.

Progress outcomes have replaced the previous achievement objectives. The progress outcomes specify what students should know and be able to do by the end of each phase of learning.

Schools are expected to use the Refreshed Curriculum to develop their own school curriculum.

While there is more specificity in the Refreshed Curriculum, schools are still expected to localise it. The Refreshed Curriculum identifies the learning that mattersuse this to design their school curriculum and develop content that can be taught to students in their classrooms. Each school curriculum will be unique. This flexibility is intended to enable schools to:

- be responsive to the needs, identity, language, culture, interests, strengths, and aspirations of their learners and their families

- have a clear focus on what supports the progress of all learners

- integrate Te Tiriti o Waitangi into classroom learning

- help learners engage with the knowledge, values, and competencies, so they can go on and be confident and connected lifelong learners.(6)

To develop their school curriculum for ANZ Histories, schools are encouraged to work with local whānau, hapū, and iwi.

Schools are expected to be working with their local communities, including hapū and iwi. For the implementation of ANZ Histories, schools are specifically guided to build productive and enduring partnerships with local whānau, hapū, and iwi, to understand and plan for the changes to their school curriculum content for ANZ Histories, especially for the ‘big idea’ - ‘Māori history is the foundational and continuous history of Aotearoa New Zealand.’(7)

The Ministry has provided a range of resources, supports, and professional learning opportunities to help schools localise and teach the ANZ Histories content.

Key supports include teaching resources available online(8) and regionally allocated professional learning and development about ANZ Histories. Schools can also ask for support from the Ministry’s Curriculum Leads, who can provide support to understand the national curriculum and to design quality and inclusive learning experiences for students.

What we looked at

ERO is working in partnership with the Ministry of Education (the Ministry) to evaluate the implementation of the Refreshed Curriculum. This is phase one of a multi-year evaluation that will provide real-time insights to inform and adjust the curriculum refresh as it is happening. The lessons can be used to inform implementation of the future curriculum changes.

We started with the evaluation of the Social Sciences learning area, including ANZ Histories, because this is the first learning area to be refreshed. We set out to answer the following questions.

- What is being taught for ANZ Histories?

- What has been the impact of ANZ Histories on students, teachers, and communities?

- What has been working well and less well in making the changes to include ANZ Histories?

- What is being taught for the refreshed Social Sciences learning area more broadly, and what impact is it having?

- What are the lessons for ANZ Histories and for implementing other curriculum areas?

This report focuses mainly on ANZ Histories because this is the only part of the refreshed Social Sciences learning area that is compulsory so far and is where most of the change is happening.

Where we looked

We engaged with curriculum leaders and teachers in primary and secondary schools who have responsibility for delivering Social Sciences content. In some schools, the curriculum leaders are principals or deputy principals. Throughout the report, we simply refer to ‘leaders.’

We focused on students in Years 4-10, and parents and whānau of students in Years 1-10.

We also spoke with a range of experts, including experts in curriculum design and people with other relevant subject matter expertise. We also spoke to a kaumatua of a hapū about their work with a local school to develop and implement ANZ Histories.

We have taken a robust, mixed-methods approach to deliver breadth and depth, including:

- site visits at 11 schools

- surveys of 447 school leaders and teachers

- surveys of 918 students

- surveys of 1016 parents and whānau

- interviews with 37 school leaders and 52 teachers

- interviews with 96 students

- interviews with 22 parents and whānau

- interviews with six experts in curriculum and/or relevant subject matter

- interview with one hapū representative.

We collected the data in late Term 3 and early Term 4 of 2023, when schools were meant to have been teaching ANZ histories to all students in Years 1 to 10 for at least two terms.

More details about our methodology are in Appendix 1.

Report structure

This report is divided into seven parts.

Part 1 describes what is happening in schools following the requirement to teach ANZ Histories and the availability of the Refreshed Curriculum content for the wider Social Sciences.

Part 2 looks at the impact for students so far, of learning ANZ Histories, focusing on how engaged and included they are and what progress they are making.

Part 3 looks at the impact for school leaders and teachers, focusing on their understanding of the ANZ Histories content, their confidence to teach it, their enjoyment of teaching it, and their capacity to implement the changes required.

Part 4 looks at the impact for parents and whānau, focusing on what they know about the curriculum changes, whether they are involved with the changes through their child’s school, what they think is important about ANZ Histories, and what impacts they are seeing so far.

Part 5 looks at the impact of the wider refreshed Social Sciences learning area, as far as is possible at this stage of the implementation.

Part 6 looks at what has worked and hasn’t worked in the implementation, so far, of ANZ Histories and the wider refreshed Social Sciences, with a focus on teacher capability and confidence, resources and supports, partnerships, and ways of working.

Part 7 sets out our key findings and lessons for the ongoing implementation of ANZ Histories, the wider refreshed Social Sciences, and other learning areas being updated as part of the curriculum refresh.

Part 1: What is happening?

ANZ Histories is being taught in all schools but not yet all year levels, and the extent to which it is being taught varies. Primary schools are more likely to be teaching it. We found that schools are prioritising local and Māori histories and teaching less about national and global contexts. Schools also have a stronger focus on teaching about culture and identity, and place and environment, than economic activity and government and organisations. Schools are prioritising teaching ANZ Histories over the wider Social Sciences.

What we looked at

We wanted to know about the changes taking place in schools and classrooms for the refresh of the Social Sciences learning area, including ANZ Histories. For this, we asked school leaders and teachers:

- if they are teaching ANZ Histories and to which year levels

- what is being taught for ANZ Histories

- what is happening for the broader Social Sciences learning area.

How we gathered this information

The findings in this section are based on:

- surveys of school leaders and teachers

- interviews with school leaders and teachers

- interviews with experts in curriculum design and/or relevant subject matter.

We collected our data in late Term 3 and early Term 4 of 2023.

What we found: An overview

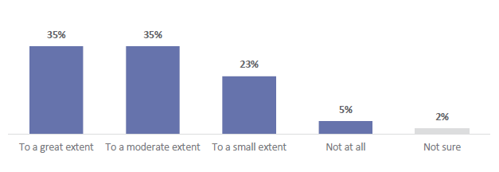

ANZ Histories became compulsory at the start of 2023. ANZ Histories content is being taught in all schools, and three-quarters are teaching it at all year levels. Nine in 10 (90 percent) schools expect to have implemented ANZ Histories across all year levels by the end of 2024. Primary schools are more likely to be teaching it, but secondary schools are teaching it to a greater extent.

Teachers need to weave the Understand, Know, Do together but so far are mainly focusing on the Know. This is in part because teachers see the Know element as the biggest shift in the Refreshed Curriculum. Part of unpacking and developing teachers’ understanding of the Know is developing a shared understanding of local histories for the school.

Both primary and secondary schools told us that the Do inquiry practices are not yet a focus in their teaching of ANZ Histories. This matters because the inquiry practices help students to be critical thinkers.

Schools are focusing on some of the big ideas and contexts more than others. Schools are prioritising the big ideas related to Māori history and colonisation more than relationships across boundaries, and the use of power. For the Know contexts, schools are prioritising cultural and identity, and place and environment, over government and organisation, and economic activity.

The curriculum statements are being interpreted by schools so that they are focusing on local histories rather than national events, and local is sometimes interpreted as only Māori histories. This may be a matter of sequencing, as schools are engaging with local hapū or iwi as a starting point for implementation.

Schools are teaching less about global histories and contexts. Some schools are choosing to only look at New Zealand’s role in global histories, without exploring those histories more widely. This can limit students’ understanding of global histories and undermine enjoyment, as students like to learn about other places and cultures.

Schools are prioritising the implementation of ANZ Histories over the wider Social Sciences curriculum content. This is crowding out other areas of the Social Sciences, which is concerning for teachers who think students are missing out on a balanced curriculum.

In the following section we set out these findings in more detail on:

- How much ANZ Histories is being taught

- What is being taught for ANZ Histories

- What is happening for the broader Social Sciences.

a) How much ANZ Histories is being taught?

Although it was compulsory for all schools to be teaching ANZ Histories to all students (up to Year 10) from the start of 2023, not all schools are yet teaching it across all year levels.

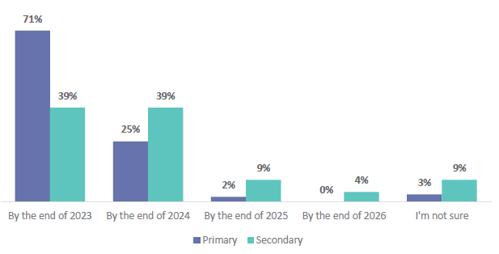

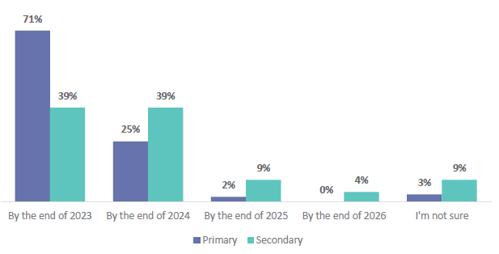

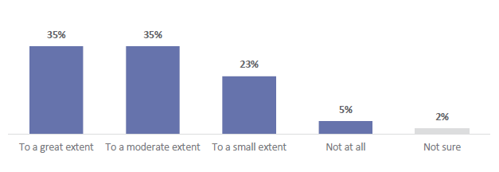

Only six in 10 (60 percent) schools plan to have implemented ANZ Histories across all school years by the end of 2023. This increases to nine in 10 (90 percent) by the end of 2024. Schools were still in the process of implementing their ANZ Histories curriculum content when ERO collected data (late Term 3 and early Term 4 of 2023). At this time, all schools were teaching some ANZ Histories curriculum content, and to most years, but only three-quarters (77 percent) of schools were teaching it at all year levels (up to Year 10).

Primary schools have been faster than secondary schools to adopt ANZ Histories.

Four in five (81 percent) primary schools are teaching at least some ANZ Histories at all year levels and almost three-quarters (74 percent) of secondary schools are teaching some ANZ Histories to Years 9 and 10.

More primary schools were planning to have implemented ANZ Histories to all year levels (up to Year 10) by the end of 2023 than secondary schools (71 percent and 39 percent respectively). Concerningly, nearly one in 10 (9 percent) secondary school leaders were unsure when ANZ Histories would be fully implemented.

Figure 3: Schools’ implementation plan for ANZ Histories across all year levels (up to Year 10)

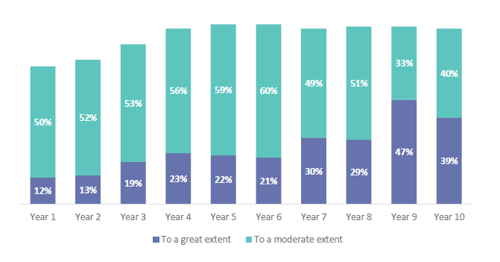

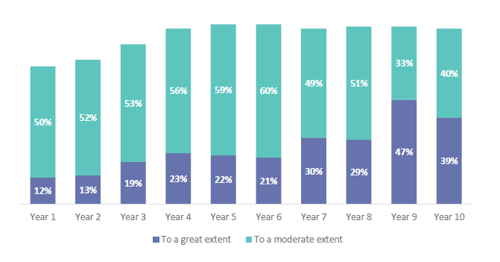

Secondary schools are teaching ANZ Histories to a greater extent than primary schools.

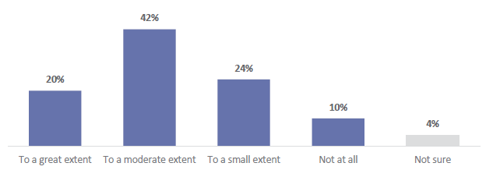

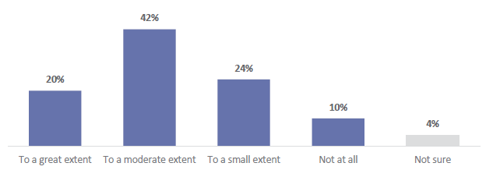

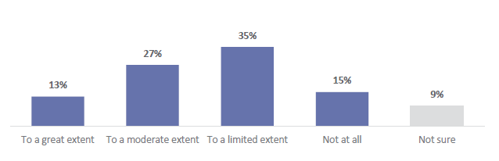

Around five in 10 (47 percent) of secondary leaders reported that ANZ Histories was being taught ‘to a great extent’ in Year 9 and around four in 10 (39 percent) reported it was being taught ‘to a great extent’ in Year 10.

Only around one in eight primary leaders reported that ANZ Histories was being taught ‘to a great extent’ in Years 1 and 2 (12 percent and 13 percent respectively), and around one in five in Years 3 to 6 (19 percent, 23 percent, 22 percent, and 21 percent respectively). This increased to about one in three leaders who were teaching ANZ Histories ’to a great extent’ in Years 7 and 8 (30 percent and 29 percent respectively).

Figure 4: Extent to which ANZ Histories has been taught, by year levels

b) What is being taught for ANZ Histories?

Overall framework

What schools need to teach is set out in the Understand, Know, Do framework.

We heard that teachers and leaders like the specificity of the Understand, Know, Do framework, but would like more guidance on how to use this across different year levels. It was also familiar to some teachers and leaders. They identified links with other frameworks (9) they are already using, which gave them greater confidence to use it.

However, we heard that the framework was still very broad. Some teachers liked this broadness because it gave them ‘room to move’. Other teachers said the broadness created ‘vagueness’ – they could tag some content to whatever they wanted. Teachers, specifically, wanted more detail on how to plan for teaching the Understand, Know, Do across year levels. The progressions are meant to help with this, but teachers told us that planning is not a simple process.

“The ‘Understand, Know, Do’ kaupapa is not intuitive/easy to grasp. [It] is a shift in approach which (in my opinion) is not that well explained or illustrated in the resources provided, and is therefore the main barrier to firstly, implementing ANZ Histories and secondly, knowing whether we are implementing ANZ Histories in the desired manner. Given that U,K,D is going to be part of the Refreshed Curriculum as a whole, clearer PD (professional development) on this would be very welcome”. (School leader)

Figure 5: Elements of the ANZ Histories framework

Understand, Know, Do for Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories (ANZ Histories)Understand – the big ideas1. Māori history is the foundational and continuous history of Aotearoa New Zealand 2. Colonisation and settlement have been central to Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories for the past 200 years 3. The course of Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories has been shaped by the use of power 4. Relationships and connections between people and across boundaries have shaped the course of Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories Know – the contexts1. Culture and identity 2. Government and organisation 3. Place and environment 4. Economic activity Do – inquiry practices1. Identifying and exploring historical relationships 2. Identifying sources and perspectives 3. Interpreting past experiences, decisions, and actions |

Schools need to weave the Understand, Know, Do together, but so far they are mostly focused on the Know part of the framework.

Teachers are expected to design learning experiences that weave the Understand, Know, Do, together so that student learning is deep and meaningful. The Understand, Know, Do, elements are not supposed to be separate or in sequence.(10) However, leaders and teachers told us they are focusing their attention on unpacking and understanding the Know statements over other parts of the framework, at least for now, because the Know is less familiar to them. They told us it was the biggest shift in the Refreshed Curriculum. We heard that teachers and leaders were also starting with the Know because they had been advised to do so by the Ministry Curriculum Leads.

“[We’re] sort of thinking that it's not such a big shift from what we do anyway, but the Know part is. The Know part is going to require a bit more strategy. … That's where we need to probably do the most work in making sure that we have a good scope and sequence.” (School leader)

A big part of unpacking and understanding the Know is developing a shared understanding of local histories for the school.

Understand – the big ideas

The ‘Understand’ part of the framework describes the deep and enduring big ideas, including ideas relevant to mātauranga Māori, that students are expected to learn across their schooling.(11) The four big ideas for ANZ Histories are listed below.

- Māori history is the foundational and continuous history of Aotearoa New Zealand.

- Colonisation and settlement have been central to Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories for the past 200 years.

- The course of Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories has been shaped by the use of power.

- Relationships and connections between people and across boundaries have shaped the course of Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories.

Schools are mostly focusing on the big ideas of Māori history, and colonisation.

At this stage in the implementation, four in five (81 percent) teachers have included at least two of the big ideas in their teaching for ANZ Histories, but less than a third (29 percent) have included all four (at the time of ERO’s data collection in late Term 3 and early Term 4 of 2023).

Only half of teachers (53 percent) have included the big idea ‘relationships and connections between people and across boundaries have shaped the course of Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories’ in their teaching so far. This is the big idea that best supports the understanding of Aotearoa New Zealand’s place in the world.

Almost two in three teachers have included the big ideas ‘Māori history is the foundational and continuous history of Aotearoa New Zealand’ (64 percent) and ‘colonisation and settlement have been central to Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories for the past 200 years’ (61 percent) in their teaching. Two in five (41 percent) have included the big idea ‘the course of Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories has been shaped by the use of power’.

Figure 6: Big ideas that teachers have included in their teaching for ANZ Histories (so far)

Not all teachers understand the big ideas in the ANZ Histories curriculum content.

Primary school leaders and teachers say that that the language of the big ideas was already common in their teaching before the Refreshed Curriculum. However, they are not always clear on how the big ideas from ANZ Histories align to what they were doing before.

Additionally, leaders and teachers identified some big ideas they are teaching, that are not big ideas in the ANZ Histories content (for example, Te Tiriti o Waitangi | Treaty of Waitangi and the significance of place names).

Secondary leaders told us they are unsure how to thread the big ideas across their teaching where lessons are usually planned in isolated blocks. So, although teachers are back-mapping to what they were already teaching to help with implementation, they will still have to work out how to weave in the big ideas across all relevant content for ANZ Histories.

Teachers are concerned with ‘how’ to teach the big ideas.

Teachers are aware that some histories are particularly sensitive to teach and can be divisive if not taught well. For example, topics or histories that illustrate the big idea ‘The course of Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories has been shaped by the use of power’. This helps explain why teachers can feel uncomfortable teaching outside of their own culture.

Teachers are especially worried about getting Māori histories wrong and about the risk of ‘cultural appropriation’. This is why many schools are engaging with local hapū and iwi as a starting point for implementation of ANZ Histories. This collaboration with local hapū and iwi can also give them access to teaching support and helpful resources for sensitive topics.

“We had a teacher only day led by [the local iwi], and we did a hīkoi going to all the historical areas. And if you asked any teacher, that's possibly the most powerful [PLD] that they've ever had. So that got us really excited and motivated.” (School leader)

Know – the contexts

The Know part of the framework is the contexts. They are meaningful and important knowledge (concepts, generalisations, explanations, and stories) that exemplify the big ideas.(12) The four contexts for ANZ Histories are listed below.

- Culture and identity: this focuses on how the past shapes who we are today – our familial links and bonds, our networks and connections, our sense of obligation, and the stories woven into our collective and diverse identities.

- Government and organisation: this focuses on the history of authority and control, and the contests over them. At the heart of these contests are the authorities guaranteed by Te Tiriti o Waitangi | The Treaty of Waitangi. This context also considers the history of the relationships between government agencies and the people who lived here and in the Pacific.

- Place and environment: this focuses on the relationships of individuals, groups, and communities with the land, water, and resources, and on the history of contests over their control, use, and protection.

- Economic activity: this focuses on the choices people made to meet their needs and wants, how they made a living individually and collectively, and the resulting exchanges and interconnections.

Schools are focusing on teaching culture and identity, and place and environment.

So far, almost eight in 10 (77 percent) teachers have included the ‘culture and identity’ context and seven in 10 (71 percent) teachers have included the ‘place and environment’ context in their teaching of ANZ Histories.

Figure 7: Contexts that teachers have included in their teaching for ANZ Histories (so far)

Teachers say they are prioritising culture and identity because they see how it might support students to belong and think about their own perspectives on the world.

Teachers are not putting as much emphasis on teaching about government and organisation, and economic activity.