Related Insights

Explore related documents that you might be interested in.

Read Online

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank all the school leaders, teachers, board members, Professional learning development (PLD) providers, and others who shared their experiences, views, and insights through interviews, discussions, and surveys. We thank you for giving your time and sharing your stories so that others may benefit from your successes and challenges.

We sincerely thank the thousands of school leaders, teachers, board members, and PLD providers who responded to our surveys. We also extend our gratitude to the 20 schools that accommodated our research team on visits, organising time in their school day for us to talk to leaders, teachers and board members. We also thank PLD providers who supported this work and contributed their expertise – your role in strengthening teaching and learning is deeply valued.

We thank those who provided insights and information to inform our understandings. We also thank those who reviewed drafts and provided feedback

We acknowledge and thank all the school leaders, teachers, board members, Professional learning development (PLD) providers, and others who shared their experiences, views, and insights through interviews, discussions, and surveys. We thank you for giving your time and sharing your stories so that others may benefit from your successes and challenges.

We sincerely thank the thousands of school leaders, teachers, board members, and PLD providers who responded to our surveys. We also extend our gratitude to the 20 schools that accommodated our research team on visits, organising time in their school day for us to talk to leaders, teachers and board members. We also thank PLD providers who supported this work and contributed their expertise – your role in strengthening teaching and learning is deeply valued.

We thank those who provided insights and information to inform our understandings. We also thank those who reviewed drafts and provided feedback

Executive summary

High-quality teaching is essential for ensuring students do well at school. One of the best ways to improve teaching quality is through professional learning and development (PLD) for teachers. Teacher development helps teachers build their expertise, learn proven teaching methods, and improve their classroom practice. This leads to better learning and achievement for students.

The Education Review Office (ERO) looked at how learning and development works for teachers in New Zealand. We looked at how good it is, and what impact it has on teaching and student outcomes. This summary sets out the key findings and recommendations to improve teacher development in New Zealand.

What is professional learning and development (PLD)?

All registered teachers in New Zealand hold a teaching qualification, which gives them the skills and knowledge to begin teaching. However, this is just the starting point. Ongoing teacher development helps teachers develop their expertise, knowledge, stay up-to-date with new evidence, and keep improving their practice.

Teacher development can take a variety of forms. For example, teachers participate in in-house sessions led by school leaders or expert teachers (internal PLD), or programmes and courses delivered by specialist providers from outside the school (external PLD).

Some PLD is decided and funded centrally by the Ministry of Education, for example the recent nationwide PLD to support structured maths, and PLD to support the structured literacy approaches. Other PLD is funded by the school.

For this report, in February and March 2025, ERO looked at all PLD for teachers in primary and secondary schools. This coincided with the nationwide rollout of English curriculum changes for teachers of Years 0-6. Just over four in ten (44 percent) primary school teachers told us about external PLD that was focussed on English.

Why does teacher development matter?

Finding 1: Quality teaching is critical for student outcomes. Developing our teachers is one of the biggest levers for raising student achievement.

- Quality teaching is the biggest driver of student success. It is more impactful than other things, including prior student achievement and class size, on students’ outcomes.

- PLD has a strong impact on improving the quality of teaching practice and enhancing student achievement.

How much do we invest in developing our teachers?

Finding 2: We invest substantially in teacher development, both centrally and in schools. In New Zealand, formal PLD is not a requirement for teachers, unlike similar professions and some other countries.

- The Ministry of Education funded $138 million for PLD in the last financial year (2024-2025).

- This funding includes $40.7 million for literacy/ Te Reo Matatini, and $1.3 million for maths/ Pāngarau.

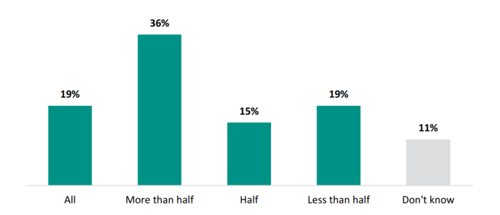

- Schools are also making a significant contribution – just over two-thirds of schools funded half or more of their PLD from their operational funds.

- On average, teachers complete about two days of internal PLD a year. In most cases, this adds up throughout the year during smaller topic-focussed activities.

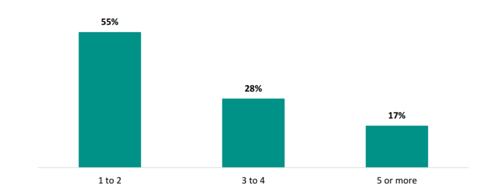

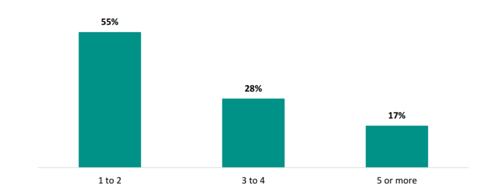

- Teachers most commonly (55 percent) complete one to two external development programmes (which can range from a stand-alone session, to a comprehensive multi-month course) per year. Another quarter (28 percent) attend three to four external development programmes per year.

- Teachers also participate in informal and ad hoc professional learning activities, such as classroom observations and mentoring, or self-paced online modules.

- Teachers’ participation in development also has a time cost, and teachers report they need to see a benefit from their participation to feel it is worth it.

- Unlike similar professions in New Zealand, or teachers in some other countries, there is no mandatory requirement for teachers to complete a set number of development hours to maintain their registration. For example, teachers in Australia are required to engage in teacher development, with the number of hours varying by state.

What is good teacher development?

Finding 3: The international evidence shows why quality PLD has the biggest impact – teachers’ development needs to be well-designed (so it is based on the best evidence) and well-selected (so it meets teachers’ needs) and well-embedded (so it sticks).

- Well-designed PLD focusses on building teachers’ knowledge, developing teaching techniques, providing practical tools, and motivating teachers.

- Well-selected PLD meets a school’s identified needs. Leaders make datadriven, evidence-backed decisions about where to focus PLD, ensuring that it is focussed on teacher needs and improving student outcomes.

- Well-embedded PLD is actively supported by school leaders. They use plans, processes, and professional supports, as well as revisiting and recapping new learning with teachers. Good support is in place for monitoring the impact of changes on teacher practice and student outcomes.

Finding 4: In New Zealand, we found external PLD that provides stepped-out teaching techniques and tools (like maths and English PLD), makes the biggest difference.

- Teachers are more than five times more likely to report an improvement in their practice when external PLD motivates them to use what they have learnt.

- Teachers are four times more likely to report an improvement when external PLD develops teaching techniques.

- Teachers are over four times more likely to report an improvement when external PLD gives teachers practical tools they can use.

Finding 5: Internal PLD provided by schools can also improve practice if it builds on what teachers know and they are motivated to use it.

- Internal PLD that supports external PLD and embeds it can be some of the most effective.

- Teachers are over four times more likely to report improved practice when internal PLD helps them build from what they know.

- Teachers are nearly five times more likely to report improved practice when they are motivated to use the internal PLD.

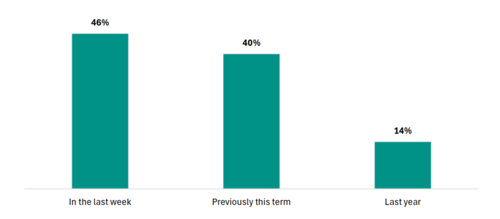

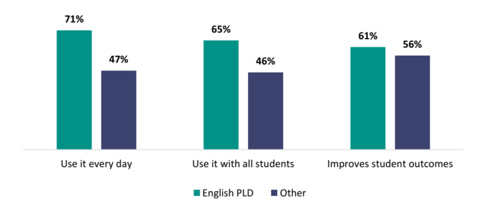

Finding 6: The recent English PLD in primary schools has been very impactful. Most teachers are using what they have learnt, using it often, and seeing improvement in student outcomes.

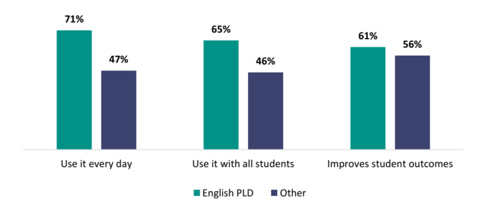

- Teachers whose most recent external PLD was on English report that they:

-

- use it often in the classroom. Nearly three-quarters (71 percent) use it every day

- use what they have learnt widely in the classroom. Two-thirds (65 percent) use it with all students

- see improvement in student outcomes. Six in ten (61 percent) report improvements in student outcomes.

- In all these areas, the recent English PLD in primary schools has had more impact than other PLD.

- Teachers report they value the evidence base of structured literacy approaches and feel confident in their ability to have an impact. This, combined with ready to-use resources and built-in mechanisms to monitor student progress, enables teachers to make immediate changes to their classroom practice and see their impacts – with a motivating effect. The nationwide rollout of the refreshed English curriculum this year added urgency and timeliness, supporting the uptake, embedding, and therefore the impact, of PLD in English.

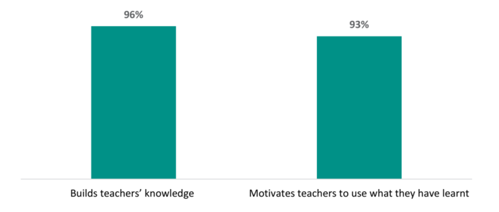

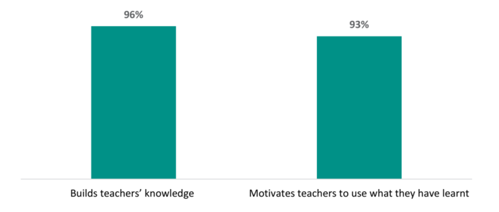

Finding 7: In New Zealand, school leaders and PLD providers are good at ensuring a strong focus on building teachers’ knowledge, motivating teachers to use PLD, and making sure it is relevant.

- More than nine out of 10 PLD providers (96 percent) focus on designing development programmes that build teachers’ knowledge and motivate teachers to use what they have learnt (93 percent).

- When school leaders select external PLD or design their own teacher development, they focus most on making sure it’s relevant to their schools’ needs. Nearly all leaders (97 percent) focus a lot on how the programme features align with their school priorities.

- We heard from school leaders that making sure teachers’ development is relevant is a key factor in their planning. Ensuring teacher development aligns with school-wide goals and strategic priorities allows it to be responsive to their school context. This makes it easier for teachers to apply what they’ve learnt and use new tools to build their expertise.

How can we strengthen development for New Zealand’s teachers?

Despite the substantial investment and the value teachers and leaders place in PLD, ERO found that not all PLD is as impactful as the recent English PLD. There are key improvements that can be made.

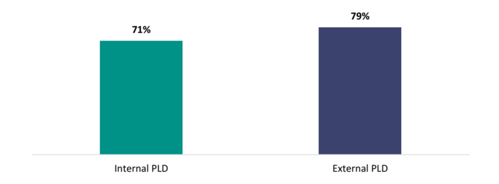

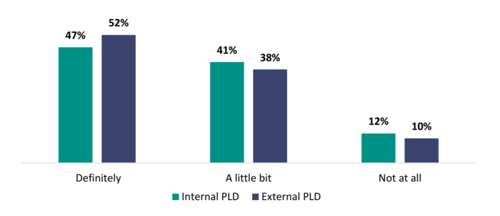

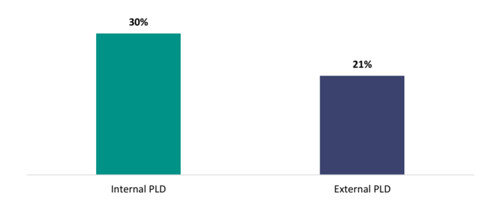

Finding 8: We need teacher development to have more impact for teachers and a stronger return on investment. Too much PLD does not shift teacher practice.

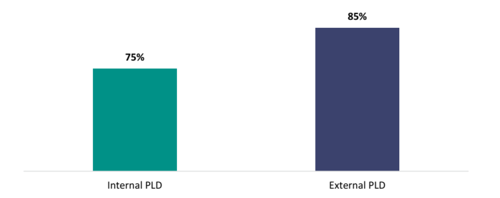

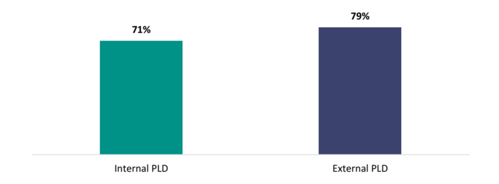

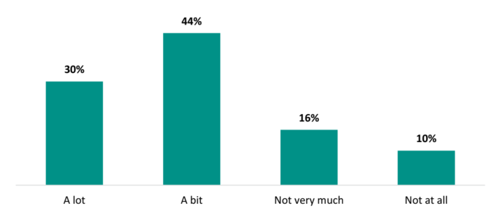

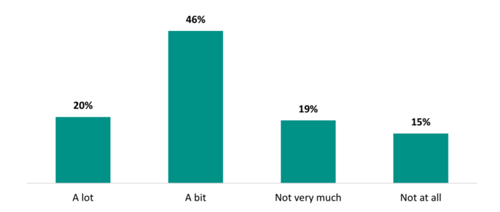

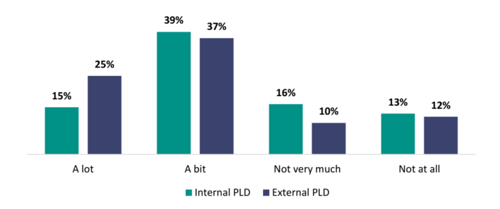

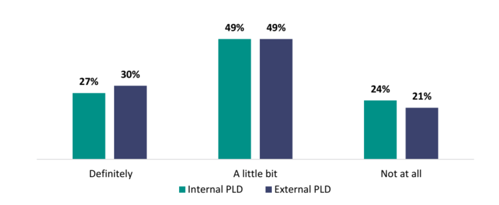

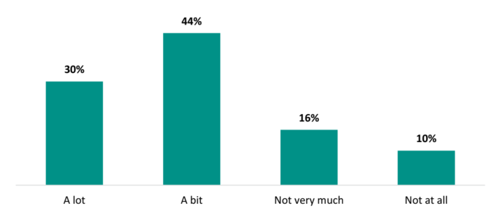

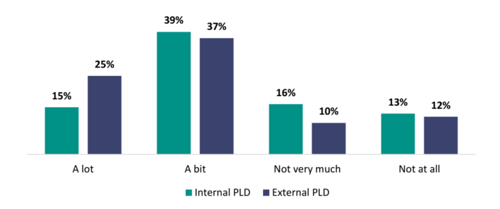

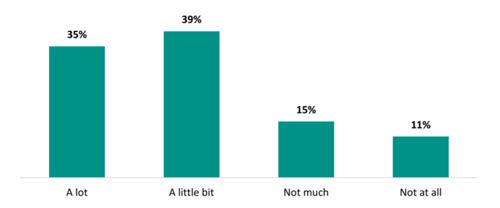

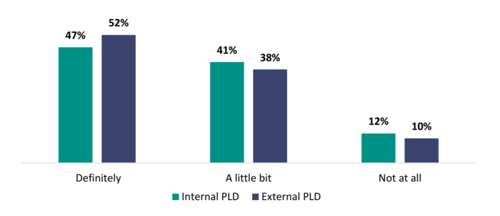

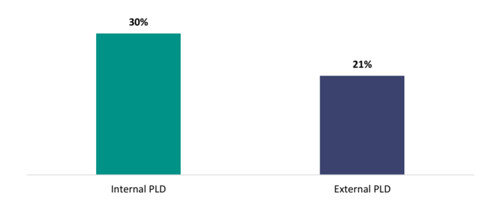

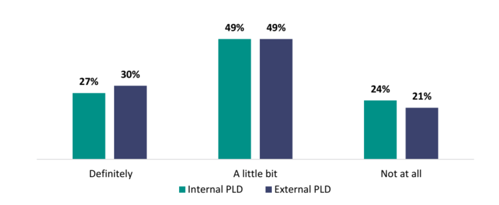

- Many teachers report little or no improvement in their teaching practice following their engagement in PLD. Just over a quarter of teachers (26 percent) report that their most recent external PLD did not improve their practice ‘very much’ or ‘at all’. This was even more for internal PLD, with just over a third (34 percent) of teachers reporting little or no improvement in their practice.

- We heard from teachers that external PLD does not always improve practice as much as intended. Often, this is because the techniques being taught are not always clearly transferrable into their classrooms.

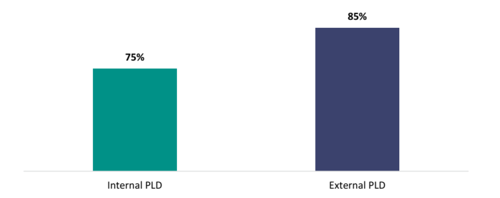

Finding 9: We need teacher development that shifts student outcomes. Around a quarter of teachers report PLD does not improve student outcomes much or at all.

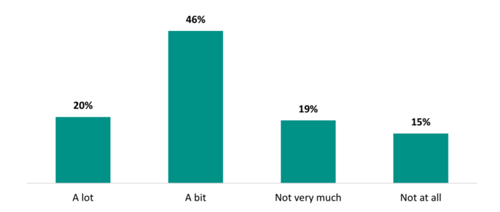

- Nearly a quarter (22 percent) of teachers report external PLD did not improve student outcomes either ‘very much’ or ‘at all’. For internal PLD, three in 10 teachers (29 percent) report student outcomes did not improve ‘very much’ or ‘at all’.

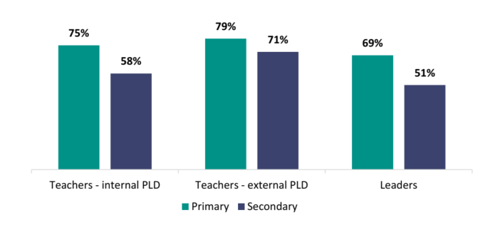

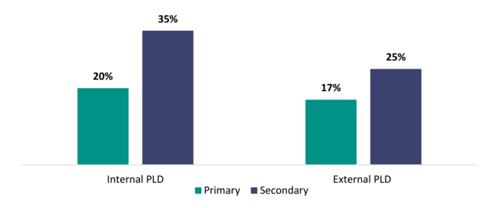

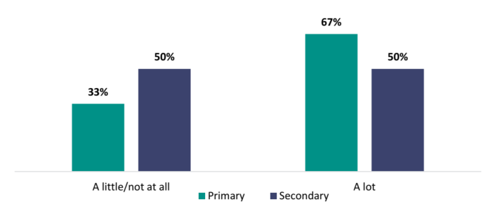

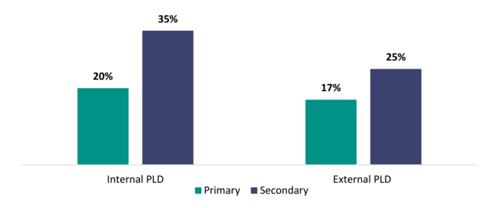

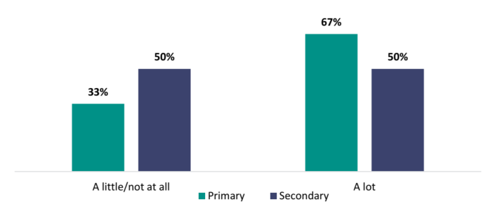

- In secondary school, internal PLD is particularly weak. Thirty-five percent of secondary teachers report it does not improve student outcomes.

Finding 10: We need to improve the design and selection of PLD, as currently it is focussed least on what matters the most.

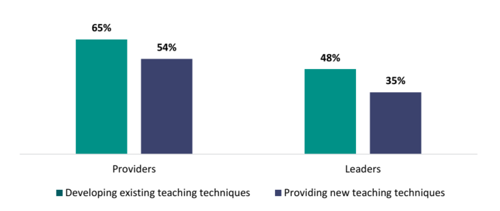

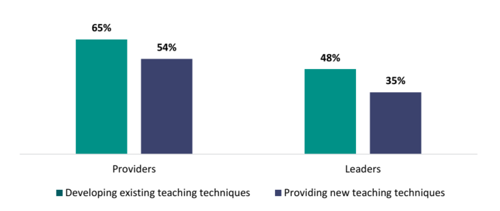

- Although developing teaching techniques is one of the most impactful things to improve teaching practice, PLD providers and leaders do not focus on this a lot. Just under two-thirds of providers (65 percent) report they do this, and even fewer leaders, with under half (48 percent) always focussing on this when selecting development opportunities.

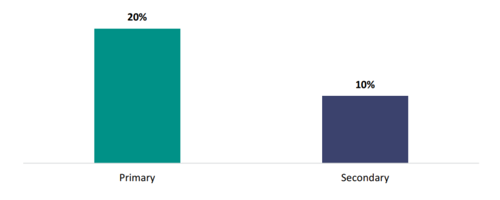

Finding 11: We need development for teachers to be better embedded, particularly in secondary schools.

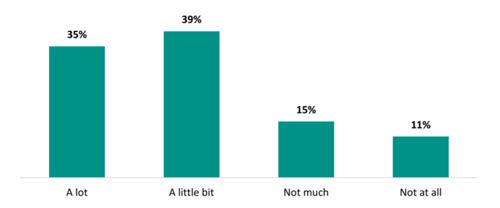

- Teachers are too often not clear on how to use what they learn from teacher development in their classroom. Half of teachers are not completely clear about how to use what they have learnt from their development in their classroom (53 percent internal PLD, 48 percent external PLD).

- We heard from teachers that teacher development often lacks practical guidance and focusses too much on theory. This leaves teachers unsure about how to apply their learning in their classroom.

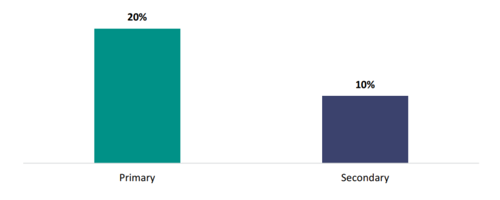

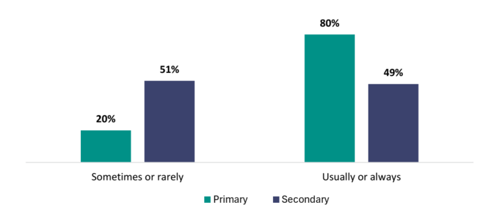

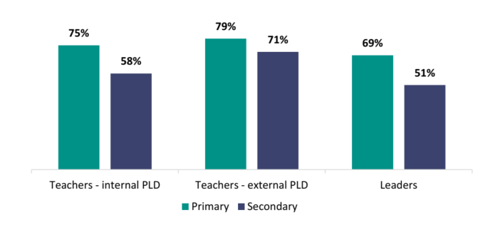

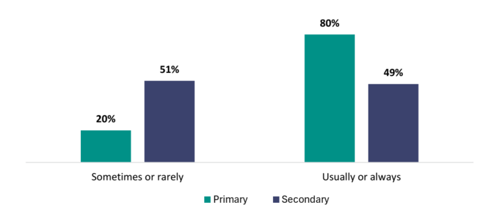

- Many teachers, especially in secondary schools, are not supported to embed what they have learnt (from both external and internal PLD). In primary schools, one in five leaders (20 percent) infrequently follow up with teachers about what they have learnt, and just over a half of secondary school leaders infrequently follow up (51 percent).

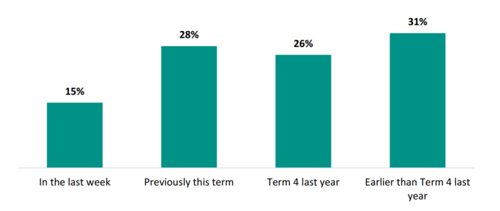

Finding 12: We need teacher development to be planned and developed over years to sustain change. Currently, it does not always build on previous learning, but instead, shifts with changing school leaders and changing priorities.

- We found that schools’ development priorities change when key personnel change. Approximately a third of schools have new principals each year, so this can have a significant impact. School leaders often select teacher development based on immediate priorities, rather than plan a coherent programme of teacher development that builds over time to develop teachers’ skills.

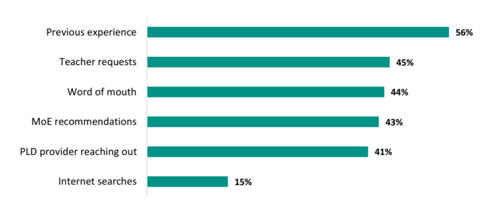

Finding 13: We need to remove the burden on leaders who find that selecting or applying for teacher development is often time-consuming and inefficient.

- Leaders report finding it difficult and time-consuming to sort through the high volume of development offerings to identify and select quality teacher development. They report juggling multiple factors when selecting programmes, often without clear guidance. For small schools, this can be a particular challenge.

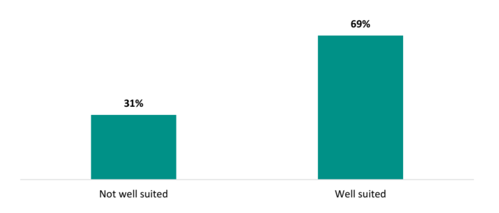

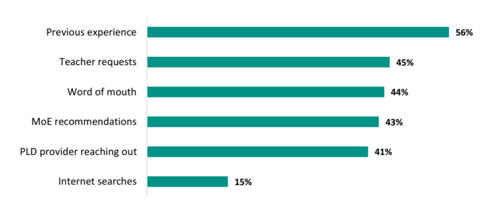

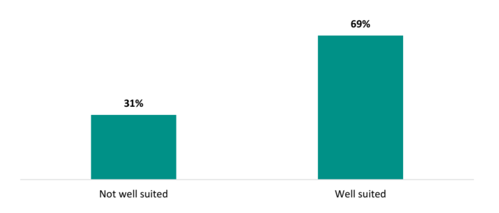

- Nearly a third of leaders (31 percent) think that the PLD available isn’t a good fit for their needs, and they are concerned about committing to PLD that is not helpful. We heard from leaders that the quality of PLD varies significantly. Leaders told us there is a lack of reliable information about PLD offerings and it is difficult to assess their quality before actually engaging in it themselves.

Finding 14: We need to do more to ensure PLD supports schools with the greatest challenges. Schools in low socioeconomic communities do not have more teacher development, despite having greater challenges. Teachers in rural or isolated schools also struggle to access development opportunities.

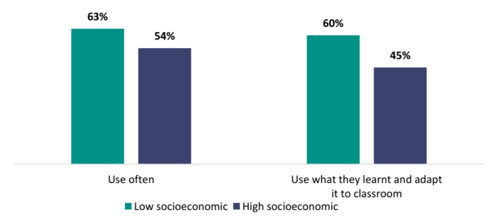

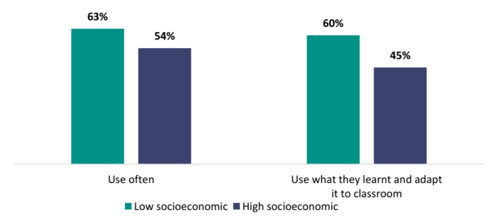

- Teachers in schools from both high and low socioeconomic communities receive the same amount of both internal and external PLD, despite schools in low socioeconomic communities having greater challenges.

- Teachers in small schools receive a similar amount of external PLD to teachers in large schools. For internal PLD, teachers in small schools are covering fewer topics than teachers in large schools, and there is an indication they may be receiving fewer hours.

- Although rural teachers attend external PLD as frequently as their peers, the nature of the PLD may differ, as there are higher costs for them attending and it is more likely to be online.

- We heard that teachers in rural and isolated schools often face long travel times for teacher development, increasing pressure on classroom practice and overreliance on online delivery. However, much of this online teacher development lacks interactivity and engagement that impacts how effective it is.

Finding 15: There is an opportunity for PLD to have the most impact in schools with more challenges.

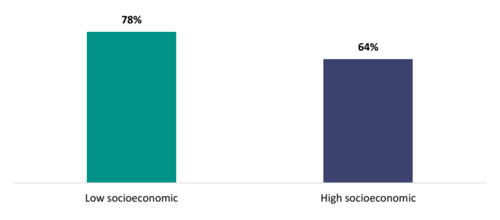

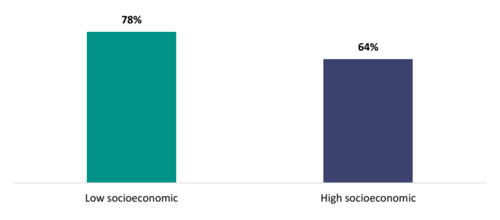

- For schools in low socioeconomic communities, teachers report that internal PLD improves practice more (78 percent), compared to teachers from schools in high socioeconomic communities (64 percent).

- Small schools often have big challenges and PLD is more impactful in small school settings. Seven in ten teachers (69 percent) from small schools use the external PLD they learnt once a week, or more, compared to 57 percent of teachers from large schools.

High-quality teaching is essential for ensuring students do well at school. One of the best ways to improve teaching quality is through professional learning and development (PLD) for teachers. Teacher development helps teachers build their expertise, learn proven teaching methods, and improve their classroom practice. This leads to better learning and achievement for students.

The Education Review Office (ERO) looked at how learning and development works for teachers in New Zealand. We looked at how good it is, and what impact it has on teaching and student outcomes. This summary sets out the key findings and recommendations to improve teacher development in New Zealand.

What is professional learning and development (PLD)?

All registered teachers in New Zealand hold a teaching qualification, which gives them the skills and knowledge to begin teaching. However, this is just the starting point. Ongoing teacher development helps teachers develop their expertise, knowledge, stay up-to-date with new evidence, and keep improving their practice.

Teacher development can take a variety of forms. For example, teachers participate in in-house sessions led by school leaders or expert teachers (internal PLD), or programmes and courses delivered by specialist providers from outside the school (external PLD).

Some PLD is decided and funded centrally by the Ministry of Education, for example the recent nationwide PLD to support structured maths, and PLD to support the structured literacy approaches. Other PLD is funded by the school.

For this report, in February and March 2025, ERO looked at all PLD for teachers in primary and secondary schools. This coincided with the nationwide rollout of English curriculum changes for teachers of Years 0-6. Just over four in ten (44 percent) primary school teachers told us about external PLD that was focussed on English.

Why does teacher development matter?

Finding 1: Quality teaching is critical for student outcomes. Developing our teachers is one of the biggest levers for raising student achievement.

- Quality teaching is the biggest driver of student success. It is more impactful than other things, including prior student achievement and class size, on students’ outcomes.

- PLD has a strong impact on improving the quality of teaching practice and enhancing student achievement.

How much do we invest in developing our teachers?

Finding 2: We invest substantially in teacher development, both centrally and in schools. In New Zealand, formal PLD is not a requirement for teachers, unlike similar professions and some other countries.

- The Ministry of Education funded $138 million for PLD in the last financial year (2024-2025).

- This funding includes $40.7 million for literacy/ Te Reo Matatini, and $1.3 million for maths/ Pāngarau.

- Schools are also making a significant contribution – just over two-thirds of schools funded half or more of their PLD from their operational funds.

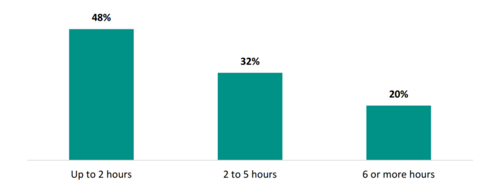

- On average, teachers complete about two days of internal PLD a year. In most cases, this adds up throughout the year during smaller topic-focussed activities.

- Teachers most commonly (55 percent) complete one to two external development programmes (which can range from a stand-alone session, to a comprehensive multi-month course) per year. Another quarter (28 percent) attend three to four external development programmes per year.

- Teachers also participate in informal and ad hoc professional learning activities, such as classroom observations and mentoring, or self-paced online modules.

- Teachers’ participation in development also has a time cost, and teachers report they need to see a benefit from their participation to feel it is worth it.

- Unlike similar professions in New Zealand, or teachers in some other countries, there is no mandatory requirement for teachers to complete a set number of development hours to maintain their registration. For example, teachers in Australia are required to engage in teacher development, with the number of hours varying by state.

What is good teacher development?

Finding 3: The international evidence shows why quality PLD has the biggest impact – teachers’ development needs to be well-designed (so it is based on the best evidence) and well-selected (so it meets teachers’ needs) and well-embedded (so it sticks).

- Well-designed PLD focusses on building teachers’ knowledge, developing teaching techniques, providing practical tools, and motivating teachers.

- Well-selected PLD meets a school’s identified needs. Leaders make datadriven, evidence-backed decisions about where to focus PLD, ensuring that it is focussed on teacher needs and improving student outcomes.

- Well-embedded PLD is actively supported by school leaders. They use plans, processes, and professional supports, as well as revisiting and recapping new learning with teachers. Good support is in place for monitoring the impact of changes on teacher practice and student outcomes.

Finding 4: In New Zealand, we found external PLD that provides stepped-out teaching techniques and tools (like maths and English PLD), makes the biggest difference.

- Teachers are more than five times more likely to report an improvement in their practice when external PLD motivates them to use what they have learnt.

- Teachers are four times more likely to report an improvement when external PLD develops teaching techniques.

- Teachers are over four times more likely to report an improvement when external PLD gives teachers practical tools they can use.

Finding 5: Internal PLD provided by schools can also improve practice if it builds on what teachers know and they are motivated to use it.

- Internal PLD that supports external PLD and embeds it can be some of the most effective.

- Teachers are over four times more likely to report improved practice when internal PLD helps them build from what they know.

- Teachers are nearly five times more likely to report improved practice when they are motivated to use the internal PLD.

Finding 6: The recent English PLD in primary schools has been very impactful. Most teachers are using what they have learnt, using it often, and seeing improvement in student outcomes.

- Teachers whose most recent external PLD was on English report that they:

-

- use it often in the classroom. Nearly three-quarters (71 percent) use it every day

- use what they have learnt widely in the classroom. Two-thirds (65 percent) use it with all students

- see improvement in student outcomes. Six in ten (61 percent) report improvements in student outcomes.

- In all these areas, the recent English PLD in primary schools has had more impact than other PLD.

- Teachers report they value the evidence base of structured literacy approaches and feel confident in their ability to have an impact. This, combined with ready to-use resources and built-in mechanisms to monitor student progress, enables teachers to make immediate changes to their classroom practice and see their impacts – with a motivating effect. The nationwide rollout of the refreshed English curriculum this year added urgency and timeliness, supporting the uptake, embedding, and therefore the impact, of PLD in English.

Finding 7: In New Zealand, school leaders and PLD providers are good at ensuring a strong focus on building teachers’ knowledge, motivating teachers to use PLD, and making sure it is relevant.

- More than nine out of 10 PLD providers (96 percent) focus on designing development programmes that build teachers’ knowledge and motivate teachers to use what they have learnt (93 percent).

- When school leaders select external PLD or design their own teacher development, they focus most on making sure it’s relevant to their schools’ needs. Nearly all leaders (97 percent) focus a lot on how the programme features align with their school priorities.

- We heard from school leaders that making sure teachers’ development is relevant is a key factor in their planning. Ensuring teacher development aligns with school-wide goals and strategic priorities allows it to be responsive to their school context. This makes it easier for teachers to apply what they’ve learnt and use new tools to build their expertise.

How can we strengthen development for New Zealand’s teachers?

Despite the substantial investment and the value teachers and leaders place in PLD, ERO found that not all PLD is as impactful as the recent English PLD. There are key improvements that can be made.

Finding 8: We need teacher development to have more impact for teachers and a stronger return on investment. Too much PLD does not shift teacher practice.

- Many teachers report little or no improvement in their teaching practice following their engagement in PLD. Just over a quarter of teachers (26 percent) report that their most recent external PLD did not improve their practice ‘very much’ or ‘at all’. This was even more for internal PLD, with just over a third (34 percent) of teachers reporting little or no improvement in their practice.

- We heard from teachers that external PLD does not always improve practice as much as intended. Often, this is because the techniques being taught are not always clearly transferrable into their classrooms.

Finding 9: We need teacher development that shifts student outcomes. Around a quarter of teachers report PLD does not improve student outcomes much or at all.

- Nearly a quarter (22 percent) of teachers report external PLD did not improve student outcomes either ‘very much’ or ‘at all’. For internal PLD, three in 10 teachers (29 percent) report student outcomes did not improve ‘very much’ or ‘at all’.

- In secondary school, internal PLD is particularly weak. Thirty-five percent of secondary teachers report it does not improve student outcomes.

Finding 10: We need to improve the design and selection of PLD, as currently it is focussed least on what matters the most.

- Although developing teaching techniques is one of the most impactful things to improve teaching practice, PLD providers and leaders do not focus on this a lot. Just under two-thirds of providers (65 percent) report they do this, and even fewer leaders, with under half (48 percent) always focussing on this when selecting development opportunities.

Finding 11: We need development for teachers to be better embedded, particularly in secondary schools.

- Teachers are too often not clear on how to use what they learn from teacher development in their classroom. Half of teachers are not completely clear about how to use what they have learnt from their development in their classroom (53 percent internal PLD, 48 percent external PLD).

- We heard from teachers that teacher development often lacks practical guidance and focusses too much on theory. This leaves teachers unsure about how to apply their learning in their classroom.

- Many teachers, especially in secondary schools, are not supported to embed what they have learnt (from both external and internal PLD). In primary schools, one in five leaders (20 percent) infrequently follow up with teachers about what they have learnt, and just over a half of secondary school leaders infrequently follow up (51 percent).

Finding 12: We need teacher development to be planned and developed over years to sustain change. Currently, it does not always build on previous learning, but instead, shifts with changing school leaders and changing priorities.

- We found that schools’ development priorities change when key personnel change. Approximately a third of schools have new principals each year, so this can have a significant impact. School leaders often select teacher development based on immediate priorities, rather than plan a coherent programme of teacher development that builds over time to develop teachers’ skills.

Finding 13: We need to remove the burden on leaders who find that selecting or applying for teacher development is often time-consuming and inefficient.

- Leaders report finding it difficult and time-consuming to sort through the high volume of development offerings to identify and select quality teacher development. They report juggling multiple factors when selecting programmes, often without clear guidance. For small schools, this can be a particular challenge.

- Nearly a third of leaders (31 percent) think that the PLD available isn’t a good fit for their needs, and they are concerned about committing to PLD that is not helpful. We heard from leaders that the quality of PLD varies significantly. Leaders told us there is a lack of reliable information about PLD offerings and it is difficult to assess their quality before actually engaging in it themselves.

Finding 14: We need to do more to ensure PLD supports schools with the greatest challenges. Schools in low socioeconomic communities do not have more teacher development, despite having greater challenges. Teachers in rural or isolated schools also struggle to access development opportunities.

- Teachers in schools from both high and low socioeconomic communities receive the same amount of both internal and external PLD, despite schools in low socioeconomic communities having greater challenges.

- Teachers in small schools receive a similar amount of external PLD to teachers in large schools. For internal PLD, teachers in small schools are covering fewer topics than teachers in large schools, and there is an indication they may be receiving fewer hours.

- Although rural teachers attend external PLD as frequently as their peers, the nature of the PLD may differ, as there are higher costs for them attending and it is more likely to be online.

- We heard that teachers in rural and isolated schools often face long travel times for teacher development, increasing pressure on classroom practice and overreliance on online delivery. However, much of this online teacher development lacks interactivity and engagement that impacts how effective it is.

Finding 15: There is an opportunity for PLD to have the most impact in schools with more challenges.

- For schools in low socioeconomic communities, teachers report that internal PLD improves practice more (78 percent), compared to teachers from schools in high socioeconomic communities (64 percent).

- Small schools often have big challenges and PLD is more impactful in small school settings. Seven in ten teachers (69 percent) from small schools use the external PLD they learnt once a week, or more, compared to 57 percent of teachers from large schools.

Recommendations

We need to build on the success of effective PLD, such as English and maths, by improving how it is designed and selected, ensuring all PLD is high quality, and making sure that it reaches the schools and teachers that need it most.

Based on these key findings, ERO has identified three priority areas for action to improve the design, selection, and embedding of quality development for teachers. Our recommendations are set out below.

Area 1: Improve the selection of teachers’ PLD

To improve the selection of teachers’ PLD, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 1: Continue investing in centralised PLD, like English and maths, that supports deliberate and sustained improvement in critical areas for improvement.

Recommendation 2: For locally developed PLD, school leaders use ERO’s clear guidance on how to select quality external PLD and design quality internal PLD.

Area 2: Ensure all PLD is high-quality

To ensure all PLD is quality, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 3: The Ministry of Education continues to track and record the impact of all nationally-funded PLD, and where PLD is not having sufficient impact, stops funding.

Recommendation 4: ERO is resourced to review any PLD provider where there are consistent concerns about the quality of PLD provided.

Recommendation 5: The Ministry of Education or ERO explore options that make it easier for leaders to select quality PLD, including considering introducing a ‘quality marking’ scheme.

Area 3: Ensure PLD reaches the schools and teachers that most need support

To better ensure all schools, teachers, and students are able to benefit from teacher practice improvements, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 6: The Ministry of Education streamlines processes for applying for centrally-funded PLD to make it less burdensome.

Recommendation 7: The Ministry of Education strengthens approaches to enable small schools and rural schools to more easily access PLD.

Recommendation 8: The Ministry of Education prioritises access to Ministry-funded PLD for schools with highest need, including schools identified by ERO as needing support.

Recommendation 9: The Ministry of Education examines options to make PLD in key areas a requirement for teachers

We need to build on the success of effective PLD, such as English and maths, by improving how it is designed and selected, ensuring all PLD is high quality, and making sure that it reaches the schools and teachers that need it most.

Based on these key findings, ERO has identified three priority areas for action to improve the design, selection, and embedding of quality development for teachers. Our recommendations are set out below.

Area 1: Improve the selection of teachers’ PLD

To improve the selection of teachers’ PLD, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 1: Continue investing in centralised PLD, like English and maths, that supports deliberate and sustained improvement in critical areas for improvement.

Recommendation 2: For locally developed PLD, school leaders use ERO’s clear guidance on how to select quality external PLD and design quality internal PLD.

Area 2: Ensure all PLD is high-quality

To ensure all PLD is quality, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 3: The Ministry of Education continues to track and record the impact of all nationally-funded PLD, and where PLD is not having sufficient impact, stops funding.

Recommendation 4: ERO is resourced to review any PLD provider where there are consistent concerns about the quality of PLD provided.

Recommendation 5: The Ministry of Education or ERO explore options that make it easier for leaders to select quality PLD, including considering introducing a ‘quality marking’ scheme.

Area 3: Ensure PLD reaches the schools and teachers that most need support

To better ensure all schools, teachers, and students are able to benefit from teacher practice improvements, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 6: The Ministry of Education streamlines processes for applying for centrally-funded PLD to make it less burdensome.

Recommendation 7: The Ministry of Education strengthens approaches to enable small schools and rural schools to more easily access PLD.

Recommendation 8: The Ministry of Education prioritises access to Ministry-funded PLD for schools with highest need, including schools identified by ERO as needing support.

Recommendation 9: The Ministry of Education examines options to make PLD in key areas a requirement for teachers

About this report

Teachers are key to student success. Like other professions, ongoing professional learning and development (PLD) is essential to develop their expertise. Evidence shows that high-quality PLD can significantly enhance teaching practice and lift student achievement.

This report examines the current PLD landscape in New Zealand – how teachers engage with PLD, and how it is chosen, designed, and delivered. We set out to understand what is working, where the gaps are, and how we can strengthen PLD.

The Education Review Office (ERO) is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early learning services, schools, and kura. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports teachers and schools to provide quality education for students. In 2025, we looked at PLD including what is working well and the challenges. ERO last reviewed PLD in 2019.1

What we looked at

For this report in February and March 2025, ERO looked at all PLD for teachers in primary and secondary schools (in English medium). We looked at:

1) What is PLD and why is it important?

2) How much PLD do teachers receive?

3) What is good quality PLD?

4) What will strengthen the quality of PLD?

Where we looked

This report focusses on the PLD that teachers receive both externally from experts, and internally within their school from leaders, colleagues, or others. We looked at PLD both funded centrally from the Ministry of Education and locally. We did not look at PLD in specialist schools, early childhood education, or kura kaupapa.

Teachers are not the only ones who receive PLD, but their PLD is the focus of this report

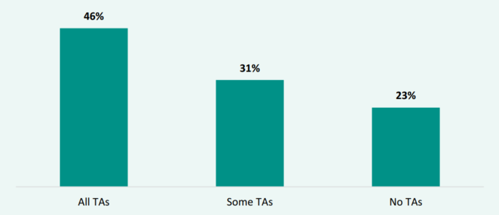

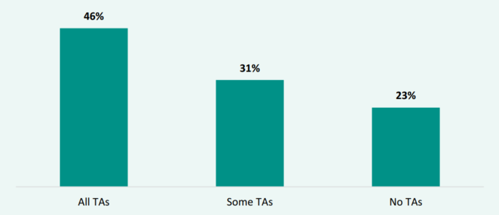

Teachers are key recipients of PLD, but school leaders and principals, teacher aides, and support staff also attend PLD either individually or as part of whole-school PLD. For example, most new principals engage in development and support opportunities when they are in their role.2 Leaders reported that nearly half of teacher aides delivering structured interventions received PLD in the last year.

Because this report focusses particularly on PLD’s impact on teaching practice and student outcomes, ERO focussed attention on the PLD received by teachers.

We used a wide range of evidence to deliver breadth and depth in this review.

We built our understanding of how PLD is selected, designed, and embedded through:

- reviewing international and local literature about quality PLD

- administrative data from the Ministry of Education

- survey responses from:

-

- 667 school leaders (556 unique schools)

- 818 teachers (354 unique schools)

- 1005 board members (669 unique schools)

- 79 PLD providers

- visits to 20 schools, covering a variety of regions and school characteristics

- interviews with:

-

- 42 leaders

- 87 teachers

- four board members

- interviews with PLD providers covering more than 10 organisations

- observations of both internal and external PLD session in practice.

As our research emphasises the need for quality PLD, we also drew heavily on international literature to understand whether current practices are informed by robust evidence that improves teaching practice, resulting in visible improvements to student outcomes.

We drew on rich insights from interviews, observations, and discussions across a diverse range of primary, intermediate, and secondary schools to understand how school leaders, teachers, and PLD providers approach the selection, design, and embedding of professional learning. These conversations offered valuable perspectives on the decision-making processes involved – and whether current practices are achieving the intended impact.

English PLD

It is useful to note that the timing of this national review coincided with the nationwide rollout of English curriculum changes for teachers of Years 0-6. Our surveys asked teachers to reflect on their most recent PLD, so just over four in ten (44 percent) primary school teachers reported on external PLD that was focussed on English. (For a discussion of findings specifically about this, see Chapter 4.)

Report structure

This report is divided into five chapters.

- Chapter 1 sets out the context of what PLD is and its importance in creating positive outcomes. We also investigate how PLD works in New Zealand, and how this compares to other professions and countries.

- Chapter 2 examines how much we invest in developing our teachers, with a focus on where funding comes from, how much teachers get, and how teachers engage in internal and external PLD.

- Chapter 3 outlines what good quality PLD looks like by drawing on literature about selection, design, and embedding. It reports what the evidence shows matters the most in New Zealand and highlights what is good about current PLD in New Zealand

- Chapter 4 explores what the evidence shows would strengthen PLD in New Zealand.

- Chapter 5 sets out our key recommendations for action that will help improve PLD.

Teachers are key to student success. Like other professions, ongoing professional learning and development (PLD) is essential to develop their expertise. Evidence shows that high-quality PLD can significantly enhance teaching practice and lift student achievement.

This report examines the current PLD landscape in New Zealand – how teachers engage with PLD, and how it is chosen, designed, and delivered. We set out to understand what is working, where the gaps are, and how we can strengthen PLD.

The Education Review Office (ERO) is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early learning services, schools, and kura. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports teachers and schools to provide quality education for students. In 2025, we looked at PLD including what is working well and the challenges. ERO last reviewed PLD in 2019.1

What we looked at

For this report in February and March 2025, ERO looked at all PLD for teachers in primary and secondary schools (in English medium). We looked at:

1) What is PLD and why is it important?

2) How much PLD do teachers receive?

3) What is good quality PLD?

4) What will strengthen the quality of PLD?

Where we looked

This report focusses on the PLD that teachers receive both externally from experts, and internally within their school from leaders, colleagues, or others. We looked at PLD both funded centrally from the Ministry of Education and locally. We did not look at PLD in specialist schools, early childhood education, or kura kaupapa.

Teachers are not the only ones who receive PLD, but their PLD is the focus of this report

Teachers are key recipients of PLD, but school leaders and principals, teacher aides, and support staff also attend PLD either individually or as part of whole-school PLD. For example, most new principals engage in development and support opportunities when they are in their role.2 Leaders reported that nearly half of teacher aides delivering structured interventions received PLD in the last year.

Because this report focusses particularly on PLD’s impact on teaching practice and student outcomes, ERO focussed attention on the PLD received by teachers.

We used a wide range of evidence to deliver breadth and depth in this review.

We built our understanding of how PLD is selected, designed, and embedded through:

- reviewing international and local literature about quality PLD

- administrative data from the Ministry of Education

- survey responses from:

-

- 667 school leaders (556 unique schools)

- 818 teachers (354 unique schools)

- 1005 board members (669 unique schools)

- 79 PLD providers

- visits to 20 schools, covering a variety of regions and school characteristics

- interviews with:

-

- 42 leaders

- 87 teachers

- four board members

- interviews with PLD providers covering more than 10 organisations

- observations of both internal and external PLD session in practice.

As our research emphasises the need for quality PLD, we also drew heavily on international literature to understand whether current practices are informed by robust evidence that improves teaching practice, resulting in visible improvements to student outcomes.

We drew on rich insights from interviews, observations, and discussions across a diverse range of primary, intermediate, and secondary schools to understand how school leaders, teachers, and PLD providers approach the selection, design, and embedding of professional learning. These conversations offered valuable perspectives on the decision-making processes involved – and whether current practices are achieving the intended impact.

English PLD

It is useful to note that the timing of this national review coincided with the nationwide rollout of English curriculum changes for teachers of Years 0-6. Our surveys asked teachers to reflect on their most recent PLD, so just over four in ten (44 percent) primary school teachers reported on external PLD that was focussed on English. (For a discussion of findings specifically about this, see Chapter 4.)

Report structure

This report is divided into five chapters.

- Chapter 1 sets out the context of what PLD is and its importance in creating positive outcomes. We also investigate how PLD works in New Zealand, and how this compares to other professions and countries.

- Chapter 2 examines how much we invest in developing our teachers, with a focus on where funding comes from, how much teachers get, and how teachers engage in internal and external PLD.

- Chapter 3 outlines what good quality PLD looks like by drawing on literature about selection, design, and embedding. It reports what the evidence shows matters the most in New Zealand and highlights what is good about current PLD in New Zealand

- Chapter 4 explores what the evidence shows would strengthen PLD in New Zealand.

- Chapter 5 sets out our key recommendations for action that will help improve PLD.

Chapter 1: What is PLD and why is it important?

PLD provides structured opportunities to improve teaching practice, deepen subject knowledge, and enhance student outcomes. Through PLD, teachers stay up to date with evidence-based practices that make a difference in the classroom. This chapter sets out what PLD is, why it matters, how teacher development works in New Zealand, and how this compares to other professions and countries.

This section sets out:

1) what PLD is

2) why PLD is it important

3) what the system is for teacher education in New Zealand

4) how the expectations for teachers in New Zealand compares to other professions, and to other countries’ expectations for teachers.

What we found: an overview

PLD for teachers is defined as structured and facilitated learning aimed at shifting teaching practice.

This report focusses on PLD for teachers. We also refer to this as teacher development. To align with the international evidence base, we have defined PLD as a structured and facilitated learning activity, intended to increase teaching ability and strengthen teaching practice. Teachers can participate in PLD activities facilitated and run by others in their school, or by professional PLD providers who are external to the school. Some PLD is decided and funded centrally by the Ministry of Education, for example the recent nationwide PLD to support structured maths, and PLD to support the structured literacy approaches. Other PLD is funded by the school.

Quality teaching is critical for student outcomes. Developing our teachers is one of the biggest levers for raising student achievement.

Quality teaching is the biggest driver of student success. It is more impactful than other things, including prior student achievement and class size, on students’ outcomes. PLD has a strong impact on improving the quality of teaching practice and enhancing student achievement.

These findings are set out in more detail below.

Findings

1) What is PLD?

In this report, we define PLD as a structured and facilitated activity for teachers intended to increase their teaching ability. PLD has a clear structure and aim for training. A team meeting focussing on admin or staff updates is not counted as PLD.

On-the-job learning, such as being mentored by a more experienced colleague, or receiving quick feedback on teaching, is another highly effective way to improve teaching, but is not defined as PLD for this review.

Table 1 sets out examples of the sorts of PLD that this report does and does not focus on.

Table 1: Examples of how our review has defined what PLD is and is not.

|

Professional learning and development is… |

Professional learning and development is not… |

|

School-wide, monthly after-school sessions on how to improve assessment processes in the classroom, including the use of specific assessment tools. |

A document that tells teachers how to use assessment software. |

|

A training day provided by a school leader on how to teach using structured literacy approaches. |

An information session on the new English learning area. |

|

A series of online webinars delivered by an external provider on how to teach maths. |

An email from the principal on how compliance with the one hour a day reading, writing, and maths will be monitored. |

PLD can be internal, meaning it is designed and delivered by members of a school to either individuals, groups, or as a whole-school activity. Internal PLD can be run:

- within a school, where colleagues learn from each other

- between schools, where teachers learn from teachers in other schools.

PLD can also be external, where it is run by outside facilitators, like an expert coming into the school to share a new teaching technique, or teachers attending a course. External PLD typically involves a school engaging an expert PLD provider, who facilitates a PLD programme for a whole-school or group of teachers from a school. This might take place at the school itself, or in an off-site location. It can include teachers from just one school, or from a range of schools. External PLD programmes are often focussed on a particular topic, such as Maths, or Restorative Practice. External PLD can be anything from a short, standalone seminar to multiple days spread over several months.

English PLD

Since Term 3, 2024, the Ministry of Education (the Ministry) has provided PLD to support primary school teachers in adopting structured literacy approaches. This PLD was widely promoted by the Ministry as part of mandatory curriculum changes and supported by allocated teacher-only day time, guidance, and resources. This PLD helps teachers understand well-defined teaching principles, evidence-based techniques, and use aligned assessment tools. Schools can apply to join and choose from approved providers. The PLD spans three school terms and includes at least three full-day workshops, four peer-learning sessions (called ‘communities of practice’), and ongoing support for these sessions over two additional terms.

2) Why is PLD important?

Quality teaching practice is critical for improving student outcomes. Developing our teachers is one of the biggest levers for raising student achievement.

Student achievement in New Zealand is a concern. Fewer than one in four Year 8 students (22 percent) achieve at the expected level in maths and student achievement is declining.

To improve student achievement, we need good teachers. High-quality teaching is the biggest driver of student success. It is more impactful than other areas including prior student achievement and reducing class size, on students’ outcomes.

Once teachers have completed their initial teaching qualification, ongoing PLD is one of the most effective ways to enhance quality teaching practice.

PLD enables teachers to keep up to date with important changes and developments in the profession, such as curriculum changes, and to have greater impact on student achievement. Research shows that good quality PLD has a strong impact on improving the quality of teaching practice and enhancing student achievement.

Effective PLD supports teachers to use evidence-based teaching methods, strengthens their subject knowledge, and improves the effectiveness of their teaching, leading to significant improvements in student outcomes. It is especially important for beginning teachers, as they start using what they have learnt in classrooms.

Effective PLD can also be useful for motivating teachers and supporting their career progression, which helps retain teachers in the workforce.

3) What is the system for developing teachers in New Zealand?

There are several steps to becoming a teacher in New Zealand.

There are four steps to becoming a teacher in New Zealand. To become a fully certified teacher, aspiring teachers must:

- complete an Initial Teacher Education qualification from an approved provider

- register as a teacher, and attain provisional practising certification

- complete two years of induction and mentoring

- attain full practising certification.

The Teaching Council of Aotearoa New Zealand (the Teaching Council) is the professional body for teachers. It is responsible for registering teachers and issuing provisional or full practising certificates.

The Teaching Council strongly encourages teacher to participate in ongoing learning.

While provisionally certified, beginning teachers are required to participate in induction and mentoring programmes. Once they are fully certified, there is flexibility in what teachers’ ongoing learning might look like.

Requirements for teachers are governed by the need to renew their practising certificate every three years. To do this, the Teaching Council considers evidence that teachers have: engaged in professional learning (see discussion below) within the last three years and apply that learning in practice along with other factors.

The Teaching Council does not specify what ‘satisfactory’ professional learning must look like, how structured the learning should be, or how much PLD teachers need to participate in to be considered satisfactory. Teachers must show how they are engaging in learning as part of a ‘Professional Growth Cycle’, which is a tool from the Teaching Council where teachers are expected to reflect on their practice, set clear goals, and take action to improve. Teachers meet this condition by providing an endorsement from their professional leader that they have engaged in professional learning designed to upskill their practice. This action can, but does not have to, include participating in formal PLD.

Teachers identify their learning needs and school leaders play a key role in identifying development needs across the school.

While school boards are the employer for teachers in their school, school leaders are responsible for supporting teachers’ development. This includes ensuring all teachers, including provisionally-certified and overseas-trained teachers have the skills and resources they need to succeed.

Teachers, along with school leaders, are responsible for managing their own professional development, including outlining their professional goals and identifying areas for development. They are also responsible for maintaining their teaching certification, including meeting the requirement to have completed satisfactory professional development in the last three years.

PLD is funded in a variety of ways.

Centrally-funded PLD

The Ministry funds teachers’ participation in PLD with specialist providers, focussed on specific priorities. The way this funding works has recently undergone changes. Before Term 1 2024, schools applied for PLD through a regionally-allocated PLD fund. Providers that were accredited to deliver regionally-allocated PLD often covered a range of priorities, and were responsible for the quality of facilitation themselves.

Currently, there is a shift to centrally-funded PLD. To access funding for either topic, school leaders now go through the following process:

- Apply for funding.

- If approved, enrol with an approved provider.

- Wait for the provider to confirm their enrolment with the Ministry.

- Support their staff to attend the PLD.

To become an approved provider and receive Ministry funding, PLD providers are required to demonstrate they have the experience, capacity and capability to meet the Ministry’s needs. An evaluation panel reviews submissions from providers to ensure they meet all requirements. Depending on demand, the Ministry may limit the number of providers who are approved.

Other external PLD

Schools also use their operational funding to access PLD opportunities for their staff. Operational funding is calculated based on a variety of factors, including the number of students a school has enrolled and the level of need in the school community. School boards are responsible for deciding how operational funds are spent.

Some iwi and charity groups also offer PLD for teachers, for example on local history and landmarks, or environmental initiatives.

There is currently no system for quality assurance for who is able to offer or charge for PLD. This means there is no way to know how many PLD providers there are, what they offer, or the quality of their programmes. School boards and leaders are responsible for deciding for themselves whether the offering is suitable.

Professional Learning Association New Zealand

The Professional Learning Association New Zealand (PLANZ) is the voluntary representative body for PLD providers in schools. PLANZ was established in 2016 and has a membership of around 20 PLD providers, including most, if not all, the large PLD providers in New Zealand as well as a number of the medium-sized and sole provider organisations working in both Māori – and English-medium settings. Within these organisations PLANZ represents around 300 facilitators.

Internal or peer-to-peer PLD

Many schools have significant expertise amongst their staff. School leaders often use these in-house experts to facilitate PLD within their school, at low or no cost. Schools often share this expertise with others in their community. This kind of PLD has the added advantage of the opportunity to contextualise learning to the school or specific students.

There is no targeted support or training to develop expert teachers’ ability to teach their peers. There is also no minimum standard or requirement for these teachers.

4) How does New Zealand’s PLD for teachers compare to other countries?

Other, similar professions in New Zealand set minimum time requirements for PLD and require providers to meet standards.

Teaching is a complex, varied, and continually evolving profession, overseen by a professional body that requires a minimum qualification, registration, and ongoing certification. This is similar to social work, psychology, and nursing.

Unlike social work and nursing, there is no specified time requirement for professional learning for teachers.

- The Social Workers’ Registration Board requires a minimum of 20 hours of continuous professional development per year, to maintain registration.

- The Nursing Council of New Zealand requires nurses to complete 60 hours of professional development every three years, to renew their certification.

The requirements for teachers are more similar to those for psychologists, who are expected to identify their learning objectives, develop and embed a plan for meeting these learning objectives, and review their progress against those objectives. The New Zealand Psychologists’ Board does not direct what the learning plan should include.

Whilst PLD for teachers does not have to meet specific conditions, PLD providers for some other professions do. For example, all PLD for nurses must be approved or accredited by the Nursing Council of New Zealand. This approval confirms that the programme meets national standards for assessing continuing competence and supports nurses’ professional growth. Providers must design their PLD programmes in line with the Nursing Council’s education standards to ensure quality and relevance.

Similarly, social work education programmes in New Zealand must meet the Social Workers’ Registration Board’s programme recognition standards to keep their accreditation. This includes ongoing programme reviews and monitoring, with all new programmes undergoing a formal review in their first year of delivery.

Teachers in other jurisdictions are expected and supported to complete ongoing PLD.

Because of differences in each education system, there is no PLD landscape that is exactly like ours. However, the system to train and support teachers in New Zealand is comparable to the systems in the United Kingdom (UK), Australia and Singapore. These include:

- Setting entry requirements for Initial Teacher Education.

- Certifying and hiring teachers.

- Retaining teachers.

There are some differences in the expectations for ongoing teacher education, and support for teachers to do this. The key things that are different between our system and others are:

- New Zealand emphasises the ‘professional growth cycle’ but does not mandate specific PLD hours or activities. Other OECD countries require teachers to engage in ongoing PLD to remain certified.

- PLD funding is often applied for on a case-by-case basis by schools, while other countries offer more consistent funding, centralised support, and incentives.

- Many countries have formal accreditation requirements for PLD providers, whereas New Zealand only requires accreditation for Ministry-funded providers.

Table 2 compares the New Zealand system, at a high level, with similar systems from Australia, the United Kingdom (UK), and Singapore.

Table 2: System for ongoing teacher education in New Zealand, compared to other countries

|

Process |

New Zealand |

Examples from other OECD countries |

|

Participation requirements |

The Teaching Council of New Zealand sets requirements for teachers to attain and renew certification as teachers. Teachers are required to show evidence of their engagement in professional learning and development to renew their certification every three years. |

Most OECD countries have policies for compulsory participation in continuous professional development (CPD) to maintain employment and/or for salary increases in lower secondary teachers. Singapore provides teachers with an entitlement to 100 hours per year of professional development. Participation is not mandatory. Australian teachers are required to engage in PLD, with the number of hours varying by state. Teachers in New South Wales must complete at least 100 hours of PLD over a five-year period while teachers in ACT must record and reflect on 20 hours of professional learning each teaching year. In the UK, there is no legal requirement that all teachers must engage in PLD, but it is similar to New Zealand as it is strongly expected as part of professional standards, performance management, and often to maintain employment.

|

|

Support to participate |

The Ministry of Education provides access to PLD focussed on national priorities. Schools must apply for this on a case-by-case basis. |

Singapore provides in-service training courses and programmes as well as specialised, subject specific courses. Teachers also have the opportunity to participate in experiential learning in research laboratories and in the business and community sectors. There is a structured roadmap in Singapore that has clear guidelines for PLD opportunities to be tailored to different career stages. In Australia, state-level support is available with funded PLD programmes. Schools may also apply for PLD opportunities independently.

|

|

Quality assurance |

There is no minimum standard or quality assurance for PLD providers in New Zealand. To be eligible for Ministry funding, PLD providers must be an ‘approved provider’. To become an approved provider, organisations need to demonstrate they have the organisational experience, capacity and capability to meet the Ministry’s requirements for service delivery. |

PLD providers in the UK are accredited through the UK Register of Learning Providers. While this registration doesn’t guarantee quality, it is often a pre-requisite to accessing public funding. Though not nationally consistent, there are internal and external quality assurance. Professional bodies or local authorities may also endorse specific PLD programmes. Singapore has a well-established national system for managing professional learning facilitators. It combines official certification through the Workforce Skills Qualification (WSQ) system with registration by the Ministry of Education. Clear quality standards guide how professional learning is designed to ensure relevance and impact. These systems help ensure facilitators are skilled and that training is consistent and effective. Australian states like New South Wales require PLD providers to meet formal accreditation criteria if their PLD counts towards mandatory hours, including presenter qualifications and programme quality. |

Conclusion

Like other professions, teaching is complex and evolving. Good quality teaching is a key driver of student achievement, and PLD is a powerful tool for maintaining and raising the quality of teaching once teachers are in the workforce.

PLD for teachers can take a variety of forms, and there is no specific expectation for how teachers engage in ongoing professional learning. Compared to other countries like Australia and Singapore, New Zealand does not have a clear unified quality framework for PLD. As a result, school boards and leaders must choose PLD themselves, with little assurance the PLD they are investing time and resource in is good quality.

The next chapter looks at how much we invest in developing, including how it is funded, how often teachers participate, and how much they engage in internal and external PLD.

PLD provides structured opportunities to improve teaching practice, deepen subject knowledge, and enhance student outcomes. Through PLD, teachers stay up to date with evidence-based practices that make a difference in the classroom. This chapter sets out what PLD is, why it matters, how teacher development works in New Zealand, and how this compares to other professions and countries.

This section sets out:

1) what PLD is

2) why PLD is it important

3) what the system is for teacher education in New Zealand

4) how the expectations for teachers in New Zealand compares to other professions, and to other countries’ expectations for teachers.

What we found: an overview

PLD for teachers is defined as structured and facilitated learning aimed at shifting teaching practice.

This report focusses on PLD for teachers. We also refer to this as teacher development. To align with the international evidence base, we have defined PLD as a structured and facilitated learning activity, intended to increase teaching ability and strengthen teaching practice. Teachers can participate in PLD activities facilitated and run by others in their school, or by professional PLD providers who are external to the school. Some PLD is decided and funded centrally by the Ministry of Education, for example the recent nationwide PLD to support structured maths, and PLD to support the structured literacy approaches. Other PLD is funded by the school.

Quality teaching is critical for student outcomes. Developing our teachers is one of the biggest levers for raising student achievement.

Quality teaching is the biggest driver of student success. It is more impactful than other things, including prior student achievement and class size, on students’ outcomes. PLD has a strong impact on improving the quality of teaching practice and enhancing student achievement.

These findings are set out in more detail below.

Findings

1) What is PLD?

In this report, we define PLD as a structured and facilitated activity for teachers intended to increase their teaching ability. PLD has a clear structure and aim for training. A team meeting focussing on admin or staff updates is not counted as PLD.

On-the-job learning, such as being mentored by a more experienced colleague, or receiving quick feedback on teaching, is another highly effective way to improve teaching, but is not defined as PLD for this review.

Table 1 sets out examples of the sorts of PLD that this report does and does not focus on.

Table 1: Examples of how our review has defined what PLD is and is not.

|

Professional learning and development is… |

Professional learning and development is not… |

|

School-wide, monthly after-school sessions on how to improve assessment processes in the classroom, including the use of specific assessment tools. |

A document that tells teachers how to use assessment software. |

|

A training day provided by a school leader on how to teach using structured literacy approaches. |

An information session on the new English learning area. |

|

A series of online webinars delivered by an external provider on how to teach maths. |

An email from the principal on how compliance with the one hour a day reading, writing, and maths will be monitored. |

PLD can be internal, meaning it is designed and delivered by members of a school to either individuals, groups, or as a whole-school activity. Internal PLD can be run:

- within a school, where colleagues learn from each other

- between schools, where teachers learn from teachers in other schools.

PLD can also be external, where it is run by outside facilitators, like an expert coming into the school to share a new teaching technique, or teachers attending a course. External PLD typically involves a school engaging an expert PLD provider, who facilitates a PLD programme for a whole-school or group of teachers from a school. This might take place at the school itself, or in an off-site location. It can include teachers from just one school, or from a range of schools. External PLD programmes are often focussed on a particular topic, such as Maths, or Restorative Practice. External PLD can be anything from a short, standalone seminar to multiple days spread over several months.

English PLD

Since Term 3, 2024, the Ministry of Education (the Ministry) has provided PLD to support primary school teachers in adopting structured literacy approaches. This PLD was widely promoted by the Ministry as part of mandatory curriculum changes and supported by allocated teacher-only day time, guidance, and resources. This PLD helps teachers understand well-defined teaching principles, evidence-based techniques, and use aligned assessment tools. Schools can apply to join and choose from approved providers. The PLD spans three school terms and includes at least three full-day workshops, four peer-learning sessions (called ‘communities of practice’), and ongoing support for these sessions over two additional terms.

2) Why is PLD important?

Quality teaching practice is critical for improving student outcomes. Developing our teachers is one of the biggest levers for raising student achievement.

Student achievement in New Zealand is a concern. Fewer than one in four Year 8 students (22 percent) achieve at the expected level in maths and student achievement is declining.

To improve student achievement, we need good teachers. High-quality teaching is the biggest driver of student success. It is more impactful than other areas including prior student achievement and reducing class size, on students’ outcomes.

Once teachers have completed their initial teaching qualification, ongoing PLD is one of the most effective ways to enhance quality teaching practice.

PLD enables teachers to keep up to date with important changes and developments in the profession, such as curriculum changes, and to have greater impact on student achievement. Research shows that good quality PLD has a strong impact on improving the quality of teaching practice and enhancing student achievement.

Effective PLD supports teachers to use evidence-based teaching methods, strengthens their subject knowledge, and improves the effectiveness of their teaching, leading to significant improvements in student outcomes. It is especially important for beginning teachers, as they start using what they have learnt in classrooms.

Effective PLD can also be useful for motivating teachers and supporting their career progression, which helps retain teachers in the workforce.

3) What is the system for developing teachers in New Zealand?

There are several steps to becoming a teacher in New Zealand.

There are four steps to becoming a teacher in New Zealand. To become a fully certified teacher, aspiring teachers must:

- complete an Initial Teacher Education qualification from an approved provider

- register as a teacher, and attain provisional practising certification

- complete two years of induction and mentoring

- attain full practising certification.

The Teaching Council of Aotearoa New Zealand (the Teaching Council) is the professional body for teachers. It is responsible for registering teachers and issuing provisional or full practising certificates.

The Teaching Council strongly encourages teacher to participate in ongoing learning.

While provisionally certified, beginning teachers are required to participate in induction and mentoring programmes. Once they are fully certified, there is flexibility in what teachers’ ongoing learning might look like.

Requirements for teachers are governed by the need to renew their practising certificate every three years. To do this, the Teaching Council considers evidence that teachers have: engaged in professional learning (see discussion below) within the last three years and apply that learning in practice along with other factors.

The Teaching Council does not specify what ‘satisfactory’ professional learning must look like, how structured the learning should be, or how much PLD teachers need to participate in to be considered satisfactory. Teachers must show how they are engaging in learning as part of a ‘Professional Growth Cycle’, which is a tool from the Teaching Council where teachers are expected to reflect on their practice, set clear goals, and take action to improve. Teachers meet this condition by providing an endorsement from their professional leader that they have engaged in professional learning designed to upskill their practice. This action can, but does not have to, include participating in formal PLD.

Teachers identify their learning needs and school leaders play a key role in identifying development needs across the school.

While school boards are the employer for teachers in their school, school leaders are responsible for supporting teachers’ development. This includes ensuring all teachers, including provisionally-certified and overseas-trained teachers have the skills and resources they need to succeed.

Teachers, along with school leaders, are responsible for managing their own professional development, including outlining their professional goals and identifying areas for development. They are also responsible for maintaining their teaching certification, including meeting the requirement to have completed satisfactory professional development in the last three years.

PLD is funded in a variety of ways.

Centrally-funded PLD

The Ministry funds teachers’ participation in PLD with specialist providers, focussed on specific priorities. The way this funding works has recently undergone changes. Before Term 1 2024, schools applied for PLD through a regionally-allocated PLD fund. Providers that were accredited to deliver regionally-allocated PLD often covered a range of priorities, and were responsible for the quality of facilitation themselves.

Currently, there is a shift to centrally-funded PLD. To access funding for either topic, school leaders now go through the following process:

- Apply for funding.

- If approved, enrol with an approved provider.

- Wait for the provider to confirm their enrolment with the Ministry.

- Support their staff to attend the PLD.

To become an approved provider and receive Ministry funding, PLD providers are required to demonstrate they have the experience, capacity and capability to meet the Ministry’s needs. An evaluation panel reviews submissions from providers to ensure they meet all requirements. Depending on demand, the Ministry may limit the number of providers who are approved.

Other external PLD

Schools also use their operational funding to access PLD opportunities for their staff. Operational funding is calculated based on a variety of factors, including the number of students a school has enrolled and the level of need in the school community. School boards are responsible for deciding how operational funds are spent.

Some iwi and charity groups also offer PLD for teachers, for example on local history and landmarks, or environmental initiatives.

There is currently no system for quality assurance for who is able to offer or charge for PLD. This means there is no way to know how many PLD providers there are, what they offer, or the quality of their programmes. School boards and leaders are responsible for deciding for themselves whether the offering is suitable.

Professional Learning Association New Zealand

The Professional Learning Association New Zealand (PLANZ) is the voluntary representative body for PLD providers in schools. PLANZ was established in 2016 and has a membership of around 20 PLD providers, including most, if not all, the large PLD providers in New Zealand as well as a number of the medium-sized and sole provider organisations working in both Māori – and English-medium settings. Within these organisations PLANZ represents around 300 facilitators.

Internal or peer-to-peer PLD

Many schools have significant expertise amongst their staff. School leaders often use these in-house experts to facilitate PLD within their school, at low or no cost. Schools often share this expertise with others in their community. This kind of PLD has the added advantage of the opportunity to contextualise learning to the school or specific students.