Related Insights

Explore related documents that you might be interested in.

Read Online

What is Professional Learning and Development (PLD)?

All registered teachers in New Zealand hold a teaching qualification, which gives them the skills and knowledge to begin teaching. However, this is just the starting point. Ongoing teacher development helps teachers develop their expertise, knowledge, stay up-to-date with new evidence, and keep improving their practice.

Teacher development can take a variety of forms. For example, teachers participate in in-house sessions led by school leaders or expert teachers (internal PLD), or programmes and courses delivered by specialist providers from outside the school (external PLD).

Some PLD is decided and funded centrally by the Ministry of Education, for example, the recent nationwide PLD to support structured maths, and PLD to support the structured literacy approaches. Other PLD is funded by the school.

For this report, in February and March 2025, ERO looked at all PLD for teachers in primary and secondary schools (English-medium). This coincided with the nationwide rollout of English curriculum changes for teachers of Years 0-6. Just over four in 10 (44 percent) primary school teachers told us about external PLD that was focussed on English.

All registered teachers in New Zealand hold a teaching qualification, which gives them the skills and knowledge to begin teaching. However, this is just the starting point. Ongoing teacher development helps teachers develop their expertise, knowledge, stay up-to-date with new evidence, and keep improving their practice.

Teacher development can take a variety of forms. For example, teachers participate in in-house sessions led by school leaders or expert teachers (internal PLD), or programmes and courses delivered by specialist providers from outside the school (external PLD).

Some PLD is decided and funded centrally by the Ministry of Education, for example, the recent nationwide PLD to support structured maths, and PLD to support the structured literacy approaches. Other PLD is funded by the school.

For this report, in February and March 2025, ERO looked at all PLD for teachers in primary and secondary schools (English-medium). This coincided with the nationwide rollout of English curriculum changes for teachers of Years 0-6. Just over four in 10 (44 percent) primary school teachers told us about external PLD that was focussed on English.

Why does teacher development matter?

Finding 1: Quality teaching is critical for student outcomes. Developing our teachers is one of the biggest levers for raising student achievement.

- Quality teaching is the biggest driver of student success. It is more impactful than other

- things, including prior student achievement and class size, on students’ outcomes.

- PLD has a strong impact on improving the quality of teaching practice and enhancing student achievement.

Finding 1: Quality teaching is critical for student outcomes. Developing our teachers is one of the biggest levers for raising student achievement.

- Quality teaching is the biggest driver of student success. It is more impactful than other

- things, including prior student achievement and class size, on students’ outcomes.

- PLD has a strong impact on improving the quality of teaching practice and enhancing student achievement.

How much do we invest in developing our teachers?

Finding 2: We invest substantially in teacher development, both centrally and in schools. In New Zealand, formal PLD is not a requirement for teachers, unlike similar professions and some other countries.

- The Ministry of Education funded $138 million for PLD in the last financial year (2024 to 2025).

- This funding includes $40.7 million for literacy/ Te Reo Matatini, and $1.3 million for maths/ Pāngarau.

- Schools are also making a significant contribution – just over two-thirds of schools funded half or more of their PLD from their operational funds.

- On average, teachers complete about two days of internal PLD a year. In most cases, this adds up throughout the year during smaller topic-focussed activities.

- Teachers most commonly (55 percent) complete one to two external development programmes (which can range from a stand-alone session, to a comprehensive multi-month course) per year. Another quarter (28 percent) attend three to four external development programmes per year.

- Teachers also participate in informal and ad hoc professional learning activities, such as classroom observations and mentoring, or self-paced online modules.

- Teachers’ participation in development also has a time cost, and teachers report they need to see a benefit from their participation to feel it is worth it.

- Unlike similar professions in New Zealand, or teachers in some other countries, there is no mandatory requirement for teachers to complete a set number of development hours to maintain their registration. For example, teachers in Australia are required to engage in teacher development, with the number of hours varying by state.

Finding 2: We invest substantially in teacher development, both centrally and in schools. In New Zealand, formal PLD is not a requirement for teachers, unlike similar professions and some other countries.

- The Ministry of Education funded $138 million for PLD in the last financial year (2024 to 2025).

- This funding includes $40.7 million for literacy/ Te Reo Matatini, and $1.3 million for maths/ Pāngarau.

- Schools are also making a significant contribution – just over two-thirds of schools funded half or more of their PLD from their operational funds.

- On average, teachers complete about two days of internal PLD a year. In most cases, this adds up throughout the year during smaller topic-focussed activities.

- Teachers most commonly (55 percent) complete one to two external development programmes (which can range from a stand-alone session, to a comprehensive multi-month course) per year. Another quarter (28 percent) attend three to four external development programmes per year.

- Teachers also participate in informal and ad hoc professional learning activities, such as classroom observations and mentoring, or self-paced online modules.

- Teachers’ participation in development also has a time cost, and teachers report they need to see a benefit from their participation to feel it is worth it.

- Unlike similar professions in New Zealand, or teachers in some other countries, there is no mandatory requirement for teachers to complete a set number of development hours to maintain their registration. For example, teachers in Australia are required to engage in teacher development, with the number of hours varying by state.

What is good teacher development?

Finding 3: The international evidence shows why quality PLD has the biggest impact – teachers’ development needs to be well-designed (so it is based on the best evidence) and well-selected (so it meets teachers’ needs) and well-embedded (so it sticks).

- Well-designed PLD focusses on building teachers’ knowledge, developing teaching techniques, providing practical tools, and motivating teachers.

- Well-selected PLD meets a school’s identified needs. Leaders make data-driven, evidence backed decisions about where to focus PLD, ensuring that it is focussed on teacher needs and improving student outcomes.

Well-embedded PLD is actively supported by school leaders. They use plans, processes, and professional supports, as well as revisiting and recapping new learning with teachers. Good support is in place for monitoring the impact of changes on teacher practice and student outcomes.

Finding 4: In New Zealand, we found external PLD that provides stepped-out teaching techniques and tools (like maths and English PLD), makes the biggest difference.

- Teachers are over five times more likely to report an improvement in their practice when external PLD motivates them to use what they have learnt.

- Teachers are four times more likely to report an improvement when external PLD develops teaching techniques.

- Teachers are over four times more likely to report an improvement when external PLD gives teachers practical tools they can use.

“I like PLD where you can come away with something solid and tangible that you can apply the next day.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHER

“Just getting your hands dirty – something that isn’t too theoretical. Probably something that feels like I can do this exact activity in class, as opposed to this is probably going to influence how I might start planning for something else…”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL TEACHER

Finding 5: Internal PLD provided by schools can also improve practice if it builds on what teachers know and they are motivated to use it.

- Internal PLD that supports external PLD and embeds it can be some of the most effective.

- Teachers are over four times more likely to report improved practice when internal PLD helps them build off what they know.

- Teachers are nearly five times more likely to report improved practice when they are motivated to use the internal PLD.

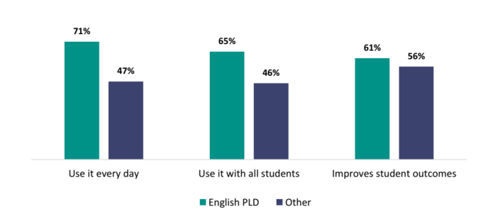

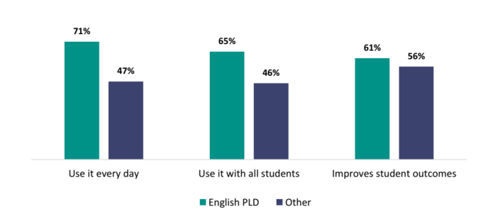

Finding 6: The recent English PLD in primary schools has been very impactful. Most teachers are using what they have learnt, using it often, and seeing improvement in student outcomes.

- Teachers whose most recent external PLD was on English report that they:

-

- use it often in the classroom. Nearly three-quarters (71 percent) use it every day

- use what they have learnt widely in the classroom. Two-thirds (65 percent) use it with all students

- see improvement in student outcomes. Six in 10 (61 percent) report improvements in student outcomes.

- In all these areas, the recent English PLD in primary schools has had more impact than other PLD.

Figure 1: Primary school teachers whose most recent external PLD was on English, compared to others.

Teachers report they value the evidence base of structured literacy approaches and feel confident in their ability to have an impact. This, combined with ready-to-use resources and built-in mechanisms to monitor student progress, enables teachers to make immediate changes to their classroom practice and see their impacts – with a motivating effect. The nationwide rollout of the refreshed English curriculum this year added urgency and timeliness, supporting the uptake, embedding, and therefore the impact, of PLD in English.

“Structured literacy programme explicitly taught us how to use the resources, how to go through the entire book and the speed word, fun ways of teaching. Understanding why it works, how it goes through all the letters, and being able to read independently and confidently...”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL BEGINNING TEACHER

“I know the scope and sequence for teaching structured literacy. My students are learning more effectively and efficiently, and my priority learners are beginning to move faster than ever before.”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL TEACHER

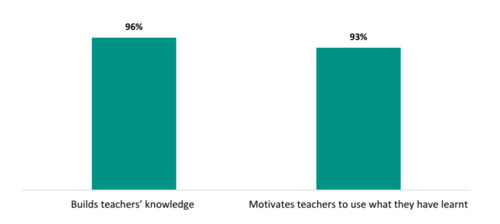

Finding 7: In New Zealand, school leaders and PLD providers are good at ensuring a strong focus on building teachers’ knowledge, motivating teachers to use PLD, and making sure it is relevant.

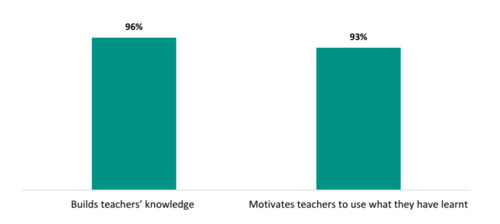

- More than nine out of 10 PLD providers (96 percent) focus on designing development programmes that build teachers’ knowledge and motivate teachers to use what they have learnt (93 percent).

Figure 2: Factors PLD providers consider when designing programmes for teachers.

- When school leaders select external PLD or design their own teacher development, they focus most on making sure it’s relevant to their schools’ needs. Nearly all leaders (97 percent) focus a lot on how the programme features align with their school priorities.

- We heard from school leaders that making sure teachers’ development is relevant is a key factor in their planning. Ensuring teacher development aligns with school-wide goals and strategic priorities allows it to be responsive to their school context. This makes it easier for teachers to apply what they’ve learnt and use new tools to build their expertise.

Finding 3: The international evidence shows why quality PLD has the biggest impact – teachers’ development needs to be well-designed (so it is based on the best evidence) and well-selected (so it meets teachers’ needs) and well-embedded (so it sticks).

- Well-designed PLD focusses on building teachers’ knowledge, developing teaching techniques, providing practical tools, and motivating teachers.

- Well-selected PLD meets a school’s identified needs. Leaders make data-driven, evidence backed decisions about where to focus PLD, ensuring that it is focussed on teacher needs and improving student outcomes.

Well-embedded PLD is actively supported by school leaders. They use plans, processes, and professional supports, as well as revisiting and recapping new learning with teachers. Good support is in place for monitoring the impact of changes on teacher practice and student outcomes.

Finding 4: In New Zealand, we found external PLD that provides stepped-out teaching techniques and tools (like maths and English PLD), makes the biggest difference.

- Teachers are over five times more likely to report an improvement in their practice when external PLD motivates them to use what they have learnt.

- Teachers are four times more likely to report an improvement when external PLD develops teaching techniques.

- Teachers are over four times more likely to report an improvement when external PLD gives teachers practical tools they can use.

“I like PLD where you can come away with something solid and tangible that you can apply the next day.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHER

“Just getting your hands dirty – something that isn’t too theoretical. Probably something that feels like I can do this exact activity in class, as opposed to this is probably going to influence how I might start planning for something else…”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL TEACHER

Finding 5: Internal PLD provided by schools can also improve practice if it builds on what teachers know and they are motivated to use it.

- Internal PLD that supports external PLD and embeds it can be some of the most effective.

- Teachers are over four times more likely to report improved practice when internal PLD helps them build off what they know.

- Teachers are nearly five times more likely to report improved practice when they are motivated to use the internal PLD.

Finding 6: The recent English PLD in primary schools has been very impactful. Most teachers are using what they have learnt, using it often, and seeing improvement in student outcomes.

- Teachers whose most recent external PLD was on English report that they:

-

- use it often in the classroom. Nearly three-quarters (71 percent) use it every day

- use what they have learnt widely in the classroom. Two-thirds (65 percent) use it with all students

- see improvement in student outcomes. Six in 10 (61 percent) report improvements in student outcomes.

- In all these areas, the recent English PLD in primary schools has had more impact than other PLD.

Figure 1: Primary school teachers whose most recent external PLD was on English, compared to others.

Teachers report they value the evidence base of structured literacy approaches and feel confident in their ability to have an impact. This, combined with ready-to-use resources and built-in mechanisms to monitor student progress, enables teachers to make immediate changes to their classroom practice and see their impacts – with a motivating effect. The nationwide rollout of the refreshed English curriculum this year added urgency and timeliness, supporting the uptake, embedding, and therefore the impact, of PLD in English.

“Structured literacy programme explicitly taught us how to use the resources, how to go through the entire book and the speed word, fun ways of teaching. Understanding why it works, how it goes through all the letters, and being able to read independently and confidently...”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL BEGINNING TEACHER

“I know the scope and sequence for teaching structured literacy. My students are learning more effectively and efficiently, and my priority learners are beginning to move faster than ever before.”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL TEACHER

Finding 7: In New Zealand, school leaders and PLD providers are good at ensuring a strong focus on building teachers’ knowledge, motivating teachers to use PLD, and making sure it is relevant.

- More than nine out of 10 PLD providers (96 percent) focus on designing development programmes that build teachers’ knowledge and motivate teachers to use what they have learnt (93 percent).

Figure 2: Factors PLD providers consider when designing programmes for teachers.

- When school leaders select external PLD or design their own teacher development, they focus most on making sure it’s relevant to their schools’ needs. Nearly all leaders (97 percent) focus a lot on how the programme features align with their school priorities.

- We heard from school leaders that making sure teachers’ development is relevant is a key factor in their planning. Ensuring teacher development aligns with school-wide goals and strategic priorities allows it to be responsive to their school context. This makes it easier for teachers to apply what they’ve learnt and use new tools to build their expertise.

How can we strengthen development for New Zealand’s teachers?

Despite the substantial investment and the value teachers and leaders place in PLD, ERO found that not all PLD is as impactful as recent English PLD. There are key improvements that can be made.

Finding 8: We need teacher development to have more impact for teachers and a stronger return on investment. Too much PLD does not shift teacher practice.

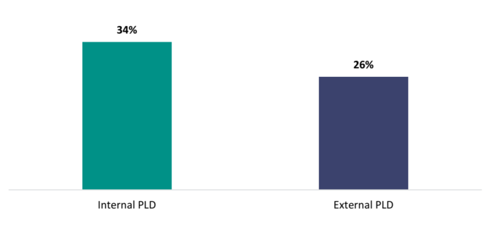

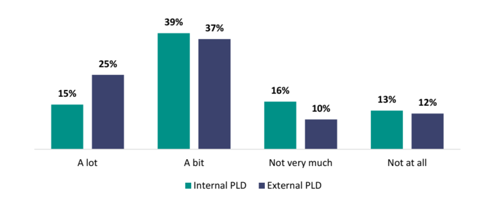

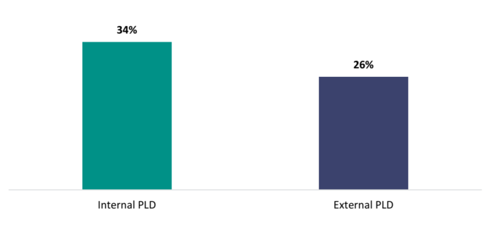

- Many teachers report little or no improvement in their teaching practice following their engagement in PLD. Just over a quarter of teachers (26 percent) report that their most recent external PLD did not improve their practice ‘very much’ or ‘at all’. This was even more for internal PLD, with just over a third (34 percent) of teachers reporting little or no improvement in their practice.

Figure 3: Proportion of teachers who say their most recent PLD didn’t improve their teaching practice very much or at all.

- We heard from teachers that external PLD does not always improve practice as much as intended. Often this is because the techniques being taught are not always clearly transferrable into their classrooms.

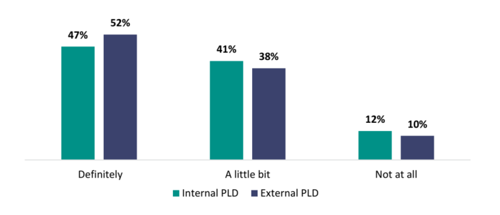

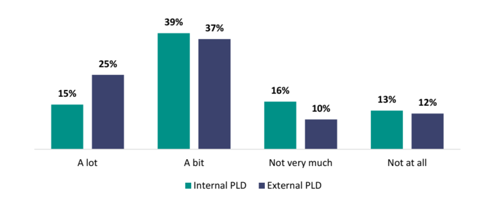

Finding 9: We need teacher development that shifts student outcomes. Around a quarter of teachers report PLD does not improve student outcomes much or at all.

- Nearly a quarter (22 percent) of teachers report external PLD did not improve student outcomes either ‘very much’ or ‘at all’. For internal PLD, three in 10 teachers (29 percent) report student outcomes did not improve ‘very much’ or ‘at all’.

- In secondary school, internal PLD is particularly weak. Thirty-five percent of secondary teachers report it does not improve student outcomes.

Figure 4: Proportion of teachers who report improvements in student outcomes following their most recent PLD.

Finding 10: We need to improve the design and selection of PLD, as currently it is focussed least on what matters the most.

- Although developing teaching techniques is one of the most impactful things to improve teaching practice, PLD providers and leaders do not focus on this a lot. Just under twothirds of providers (65 percent) report they do this, and even fewer leaders, with under half (48 percent) always focussing on this when selecting development opportunities.

Figure 5: Proportion of PLD providers and school leaders who report they focus on developing existing teaching techniques.

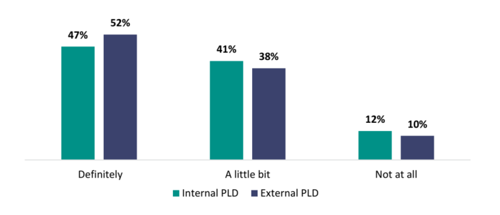

Finding 11: We need development for teachers to be better embedded, particularly in secondary schools.

- Teachers are too often not clear on how to use what they learn from teacher development in their classroom. Half of teachers are not completely clear about how to use what they have learnt from their development in their classroom (53 percent internal PLD, 48 percent external PLD).

- We heard from teachers that teacher development often lacks practical guidance and focusses too much on theory. This leaves teachers unsure about how to apply their learning in their classroom.

“All the theory, not the practical. I can go read that in my own time – I want to know practically how that works in my classroom.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHING LEADER

- Many teachers, especially in secondary schools, are not supported to embed what they have learnt (from both external and internal PLD). In primary schools, one in five leaders (20 percent) infrequently follow up with teachers about what they have learnt, and just over a half of secondary school leaders infrequently follow up (51 percent).

Figure 6: Proportion of teachers who report being clear on how to use and adapt their learning from internal and external PLD.

Finding 12: We need teacher development to be planned and developed over years to sustain change. Currently, it does not always build on previous learning, but instead, shifts with changing school leaders and changing priorities.

- We found that schools’ development priorities change when key personnel change.

- Approximately a third of schools have new principals each year, so this can have a significant impact. School leaders often select teacher development based on immediate priorities, rather than plan a coherent programme of teacher development that builds over time to develop teachers’ skills.

“[I’m] feeling a need to shift the way people are thinking about PLD, in this school specifically – there has previously been [the] attitude of, ‘Ooh something new and shiny, I want to do that,’ where things are done sporadically and not seen all the way through.”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL LEADER

Finding 13: We need to remove the burden on leaders who find that selecting or applying for teacher development is often time-consuming and inefficient.

- Leaders report finding it difficult and time-consuming to sort through the high volume of development offerings to identify and select quality teacher development. They report juggling multiple factors when selecting programmes, often without clear guidance. For small schools, this can be a particular challenge.

- Nearly a third of leaders (31 percent) think that the PLD available isn’t a good fit for their needs, and they are concerned about committing to PLD that is not helpful. We heard from leaders that the quality of PLD varies significantly. Leaders told us there is a lack of reliable information about PLD offerings and it is difficult to assess their quality before actually engaging in it themselves.

“We don’t have the time to find out what’s out there.”

- RURAL SCHOOL PRINCIPAL

“What would be quite nice [is] if the Ministry actually consolidated the offering a little bit, as providers are doing the same thing.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL DEPUTY PRINCIPAL

Finding 14: We need to do more to ensure PLD supports schools with the greatest challenges. Schools in low socioeconomic communities do not have more teacher development, despite having greater challenges. Teachers in rural or isolated schools also struggle to access development opportunities.

- Teachers in schools from both high and low socioeconomic communities receive the same amount of both internal and external PLD, despite schools in low socioeconomic communities having greater challenges.

- Teachers in small schools receive a similar amount of external PLD to teachers in large schools. For internal PLD, teachers in small schools are covering fewer topics than teachers in large schools, and there is an indication they may be receiving fewer hours.

- Although rural teachers attend external PLD as frequently as their peers, the nature of the PLD may differ, as there are higher costs for them attending and it is more likely to be online.

- We heard that teachers in rural and isolated schools often face long travel times for teacher development, increasing pressure on classroom practice and over-reliance on online delivery. However, much of this online teacher development lacks interactivity and engagement that impacts how effective it is.

“Zoom is inferior to face-to-face PLD. This means it’s inequitable, in terms of the mode of delivery that rural schools get. Access might be equitable with digital, but the mode of delivery isn’t.”

- RURAL SCHOOL PRINCIPAL

Finding 15: There is an opportunity for PLD to have the most impact in schools with more challenges.

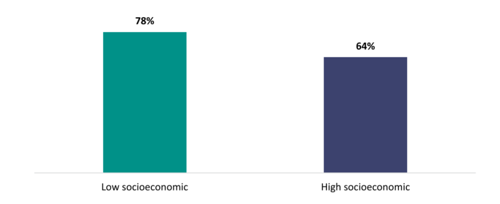

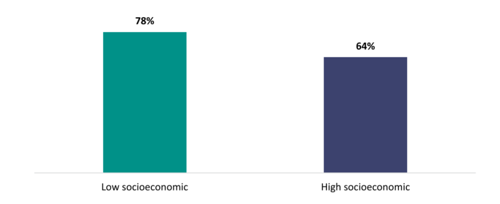

- For schools in low socioeconomic communities, teachers report that internal PLD improves practice more (78 percent), compared to teachers from schools in high socioeconomic communities (64 percent).

- Small schools often have big challenges and PLD is more impactful in small school settings. Seven in 10 teachers (69 percent) from small schools use the external PLD they learnt once a week or more, compared to 57 percent of teachers from large schools.

Figure 7: Proportion of teachers from low and high socioeconomic communities who say their most recent internal PLD improved their teaching practice.

Despite the substantial investment and the value teachers and leaders place in PLD, ERO found that not all PLD is as impactful as recent English PLD. There are key improvements that can be made.

Finding 8: We need teacher development to have more impact for teachers and a stronger return on investment. Too much PLD does not shift teacher practice.

- Many teachers report little or no improvement in their teaching practice following their engagement in PLD. Just over a quarter of teachers (26 percent) report that their most recent external PLD did not improve their practice ‘very much’ or ‘at all’. This was even more for internal PLD, with just over a third (34 percent) of teachers reporting little or no improvement in their practice.

Figure 3: Proportion of teachers who say their most recent PLD didn’t improve their teaching practice very much or at all.

- We heard from teachers that external PLD does not always improve practice as much as intended. Often this is because the techniques being taught are not always clearly transferrable into their classrooms.

Finding 9: We need teacher development that shifts student outcomes. Around a quarter of teachers report PLD does not improve student outcomes much or at all.

- Nearly a quarter (22 percent) of teachers report external PLD did not improve student outcomes either ‘very much’ or ‘at all’. For internal PLD, three in 10 teachers (29 percent) report student outcomes did not improve ‘very much’ or ‘at all’.

- In secondary school, internal PLD is particularly weak. Thirty-five percent of secondary teachers report it does not improve student outcomes.

Figure 4: Proportion of teachers who report improvements in student outcomes following their most recent PLD.

Finding 10: We need to improve the design and selection of PLD, as currently it is focussed least on what matters the most.

- Although developing teaching techniques is one of the most impactful things to improve teaching practice, PLD providers and leaders do not focus on this a lot. Just under twothirds of providers (65 percent) report they do this, and even fewer leaders, with under half (48 percent) always focussing on this when selecting development opportunities.

Figure 5: Proportion of PLD providers and school leaders who report they focus on developing existing teaching techniques.

Finding 11: We need development for teachers to be better embedded, particularly in secondary schools.

- Teachers are too often not clear on how to use what they learn from teacher development in their classroom. Half of teachers are not completely clear about how to use what they have learnt from their development in their classroom (53 percent internal PLD, 48 percent external PLD).

- We heard from teachers that teacher development often lacks practical guidance and focusses too much on theory. This leaves teachers unsure about how to apply their learning in their classroom.

“All the theory, not the practical. I can go read that in my own time – I want to know practically how that works in my classroom.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHING LEADER

- Many teachers, especially in secondary schools, are not supported to embed what they have learnt (from both external and internal PLD). In primary schools, one in five leaders (20 percent) infrequently follow up with teachers about what they have learnt, and just over a half of secondary school leaders infrequently follow up (51 percent).

Figure 6: Proportion of teachers who report being clear on how to use and adapt their learning from internal and external PLD.

Finding 12: We need teacher development to be planned and developed over years to sustain change. Currently, it does not always build on previous learning, but instead, shifts with changing school leaders and changing priorities.

- We found that schools’ development priorities change when key personnel change.

- Approximately a third of schools have new principals each year, so this can have a significant impact. School leaders often select teacher development based on immediate priorities, rather than plan a coherent programme of teacher development that builds over time to develop teachers’ skills.

“[I’m] feeling a need to shift the way people are thinking about PLD, in this school specifically – there has previously been [the] attitude of, ‘Ooh something new and shiny, I want to do that,’ where things are done sporadically and not seen all the way through.”

- PRIMARY SCHOOL LEADER

Finding 13: We need to remove the burden on leaders who find that selecting or applying for teacher development is often time-consuming and inefficient.

- Leaders report finding it difficult and time-consuming to sort through the high volume of development offerings to identify and select quality teacher development. They report juggling multiple factors when selecting programmes, often without clear guidance. For small schools, this can be a particular challenge.

- Nearly a third of leaders (31 percent) think that the PLD available isn’t a good fit for their needs, and they are concerned about committing to PLD that is not helpful. We heard from leaders that the quality of PLD varies significantly. Leaders told us there is a lack of reliable information about PLD offerings and it is difficult to assess their quality before actually engaging in it themselves.

“We don’t have the time to find out what’s out there.”

- RURAL SCHOOL PRINCIPAL

“What would be quite nice [is] if the Ministry actually consolidated the offering a little bit, as providers are doing the same thing.”

- SECONDARY SCHOOL DEPUTY PRINCIPAL

Finding 14: We need to do more to ensure PLD supports schools with the greatest challenges. Schools in low socioeconomic communities do not have more teacher development, despite having greater challenges. Teachers in rural or isolated schools also struggle to access development opportunities.

- Teachers in schools from both high and low socioeconomic communities receive the same amount of both internal and external PLD, despite schools in low socioeconomic communities having greater challenges.

- Teachers in small schools receive a similar amount of external PLD to teachers in large schools. For internal PLD, teachers in small schools are covering fewer topics than teachers in large schools, and there is an indication they may be receiving fewer hours.

- Although rural teachers attend external PLD as frequently as their peers, the nature of the PLD may differ, as there are higher costs for them attending and it is more likely to be online.

- We heard that teachers in rural and isolated schools often face long travel times for teacher development, increasing pressure on classroom practice and over-reliance on online delivery. However, much of this online teacher development lacks interactivity and engagement that impacts how effective it is.

“Zoom is inferior to face-to-face PLD. This means it’s inequitable, in terms of the mode of delivery that rural schools get. Access might be equitable with digital, but the mode of delivery isn’t.”

- RURAL SCHOOL PRINCIPAL

Finding 15: There is an opportunity for PLD to have the most impact in schools with more challenges.

- For schools in low socioeconomic communities, teachers report that internal PLD improves practice more (78 percent), compared to teachers from schools in high socioeconomic communities (64 percent).

- Small schools often have big challenges and PLD is more impactful in small school settings. Seven in 10 teachers (69 percent) from small schools use the external PLD they learnt once a week or more, compared to 57 percent of teachers from large schools.

Figure 7: Proportion of teachers from low and high socioeconomic communities who say their most recent internal PLD improved their teaching practice.

Recommendations

We need to build on the success of effective PLD, such as English and maths, by improving how it is designed and selected, ensuring all PLD is high quality, and making sure that it reaches the schools and teachers that need it most.

Based on these key findings, ERO has identified three priority areas for action to improve the design, selection, and embedding of quality development for teachers. Our recommendations are set out below.

Area 1: Improve the selection of teachers’ PLD

To improve the selection of teachers PLD, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 1: Continue investing in centralised PLD, like English and maths, that supports deliberate and sustained improvement in critical areas for improvement.

Recommendation 2: For locally developed PLD, school leaders use ERO’s clear guidance on how to select quality external PLD and design quality internal PLD.

Area 2: Ensure all PLD is high-quality

To ensure all PLD is quality, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 3: The Ministry of Education continues to track and record the impact of all nationally-funded PLD and where PLD is not having sufficient impact, stops funding.

Recommendation 4: ERO is resourced to review any PLD provider where there are consistent concerns about the quality of PLD provided.

Recommendation 5: The Ministry of Education or ERO explore options that make it easier for leaders to select quality PLD, including considering introducing a ‘quality marking’ scheme.

Area 3: Ensure PLD reaches the schools and teachers that most need support

To better ensure all schools, teachers, and students are able to benefit from teacher practice improvements, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 6: The Ministry of Education streamlines processes for applying for centrally funded PLD to make it less burdensome.

Recommendation 7: The Ministry of Education strengthens approaches to enable small schools and rural schools to more easily access PLD.

Recommendation 8: The Ministry of Education prioritises access to Ministry-funded PLD for schools with highest need, including schools identified by ERO as needing support.

Recommendation 9: The Ministry of Education examines options to make PLD in key areas a requirement for teachers.

We need to build on the success of effective PLD, such as English and maths, by improving how it is designed and selected, ensuring all PLD is high quality, and making sure that it reaches the schools and teachers that need it most.

Based on these key findings, ERO has identified three priority areas for action to improve the design, selection, and embedding of quality development for teachers. Our recommendations are set out below.

Area 1: Improve the selection of teachers’ PLD

To improve the selection of teachers PLD, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 1: Continue investing in centralised PLD, like English and maths, that supports deliberate and sustained improvement in critical areas for improvement.

Recommendation 2: For locally developed PLD, school leaders use ERO’s clear guidance on how to select quality external PLD and design quality internal PLD.

Area 2: Ensure all PLD is high-quality

To ensure all PLD is quality, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 3: The Ministry of Education continues to track and record the impact of all nationally-funded PLD and where PLD is not having sufficient impact, stops funding.

Recommendation 4: ERO is resourced to review any PLD provider where there are consistent concerns about the quality of PLD provided.

Recommendation 5: The Ministry of Education or ERO explore options that make it easier for leaders to select quality PLD, including considering introducing a ‘quality marking’ scheme.

Area 3: Ensure PLD reaches the schools and teachers that most need support

To better ensure all schools, teachers, and students are able to benefit from teacher practice improvements, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 6: The Ministry of Education streamlines processes for applying for centrally funded PLD to make it less burdensome.

Recommendation 7: The Ministry of Education strengthens approaches to enable small schools and rural schools to more easily access PLD.

Recommendation 8: The Ministry of Education prioritises access to Ministry-funded PLD for schools with highest need, including schools identified by ERO as needing support.

Recommendation 9: The Ministry of Education examines options to make PLD in key areas a requirement for teachers.

Want to know more?

To learn more about PLD in New Zealand, and what makes it effective in supporting teachers and improving student outcomes, check out our full national review report, good practice report, and short insights guides for primary and secondary school leaders.

ERO also developed a framework tool that outlines key actions and considerations for leaders. The framework is designed to be a practical tool to support school leaders to make good decisions around PLD for teachers, through planning and embedding – to make sure it’s worth it.

These can be downloaded for free from ERO’s Evidence and Insights website, www.evidence.ero.govt.nz.

To learn more about PLD in New Zealand, and what makes it effective in supporting teachers and improving student outcomes, check out our full national review report, good practice report, and short insights guides for primary and secondary school leaders.

ERO also developed a framework tool that outlines key actions and considerations for leaders. The framework is designed to be a practical tool to support school leaders to make good decisions around PLD for teachers, through planning and embedding – to make sure it’s worth it.

These can be downloaded for free from ERO’s Evidence and Insights website, www.evidence.ero.govt.nz.

ERO’s suite of professional learning and development review, practice, and support resources.

| Title | What’s it about? | Who is it for? |

| Teaching our teachers: How effective is professional learning and development? |

The review report shares what ERO found out about the PLD practices for teachers happening in our country.

|

School leaders, board members, PLD providers, experts, and the wider education sector |

| School leaders’ good practice: Professional learning and development |

The good practice report sets out how school leaders can choose, design, and embed PLD effectively.

|

School leaders, board members, PLD providers, experts, and the wider education sector |

| Insights for primary school leaders: Teachers’ professional learning and development |

This guide sets out our key findings and areas for action. It also shares examples of good practice for primary school leaders.

|

Primary school leaders, board members |

| Insights for secondary school leaders: Teachers’ professional learning and development |

This guide sets out our key findings and areas for action. It also shares examples of good practice for secondary school leaders.

|

Secondary school leaders, board members |

| Framework for school leaders – Teachers’ PLD: Making sure it’s worth it | The framework is a practical tool to support school leaders to make good decisions around PLD for teachers, through planning and embedding. | School leaders |

| Title | What’s it about? | Who is it for? |

| Teaching our teachers: How effective is professional learning and development? |

The review report shares what ERO found out about the PLD practices for teachers happening in our country.

|

School leaders, board members, PLD providers, experts, and the wider education sector |

| School leaders’ good practice: Professional learning and development |

The good practice report sets out how school leaders can choose, design, and embed PLD effectively.

|

School leaders, board members, PLD providers, experts, and the wider education sector |

| Insights for primary school leaders: Teachers’ professional learning and development |

This guide sets out our key findings and areas for action. It also shares examples of good practice for primary school leaders.

|

Primary school leaders, board members |

| Insights for secondary school leaders: Teachers’ professional learning and development |

This guide sets out our key findings and areas for action. It also shares examples of good practice for secondary school leaders.

|

Secondary school leaders, board members |

| Framework for school leaders – Teachers’ PLD: Making sure it’s worth it | The framework is a practical tool to support school leaders to make good decisions around PLD for teachers, through planning and embedding. | School leaders |

What ERO did

Data collected for this report includes:

| Who | Action |

| Over 2000 survey responses from: |

→ 667 school leaders (556 unique schools) → 818 teachers (354 unique schools) → 1005 school board members (669 unique schools) → 79 PLD providers |

| Interviews with over 140 participants, including: |

→ 42 school leaders → 87 school teachers → 4 board members → PLD providers covering more than 10 organisations |

| Site visits at: | → 20 English-medium schools |

| Observations of: |

→ One internal PLD session in practice → One external PLD session in practice |

| Data from: |

→ An in-depth review of local and international literature → Administrative data from the Ministry of Education |

We appreciate the work of those who supported this research, particularly school leaders, teachers, board members, PLD providers, and experts who have shared with us.

Their experience and insights are at the heart of what we learnt.

Data collected for this report includes:

| Who | Action |

| Over 2000 survey responses from: |

→ 667 school leaders (556 unique schools) → 818 teachers (354 unique schools) → 1005 school board members (669 unique schools) → 79 PLD providers |

| Interviews with over 140 participants, including: |

→ 42 school leaders → 87 school teachers → 4 board members → PLD providers covering more than 10 organisations |

| Site visits at: | → 20 English-medium schools |

| Observations of: |

→ One internal PLD session in practice → One external PLD session in practice |

| Data from: |

→ An in-depth review of local and international literature → Administrative data from the Ministry of Education |

We appreciate the work of those who supported this research, particularly school leaders, teachers, board members, PLD providers, and experts who have shared with us.

Their experience and insights are at the heart of what we learnt.