Related insights

Explore related documents that you might be interested in.

Read Online

Introduction

Good classroom behaviour is critical for creating learning environments in which students can learn and achieve, and teachers can be most effective. But ensuring positive behaviour isn’t just up to schools – it requires shared responsibility and deliberate, joint actions.

This report describes the challenging behaviours students and teachers face in schools, the impact of those behaviours, and recommendations for action. Our companion good practice report also shares examples of how teachers and schools can effectively manage behaviour.

Behaviour in schools impacts on learning

Classroom behaviour impacts the learning of all students. Maintaining good behaviour in school classrooms is crucial for creating an environment where students can learn and achieve. In classes with positive behaviour, teachers are able to better use their time teaching, and less time reacting to and managing behaviours. This places far less strain on their health and enjoyment of the job, allowing them to teach at their best. For students, better behaviour in classrooms means less disruptions, allowing them to focus on learning.

ERO has looked at the behaviour in classrooms in Aotearoa New Zealand and how this is changing

This evaluation report sets out what ERO has found about behaviour in classrooms and the impact of behaviour on students and teachers. The companion good practice report shares practical strategies for teachers and leaders to support improvements in managing challenging behaviour in their schools.

Good classroom behaviour is critical for creating learning environments in which students can learn and achieve, and teachers can be most effective. But ensuring positive behaviour isn’t just up to schools – it requires shared responsibility and deliberate, joint actions.

This report describes the challenging behaviours students and teachers face in schools, the impact of those behaviours, and recommendations for action. Our companion good practice report also shares examples of how teachers and schools can effectively manage behaviour.

Behaviour in schools impacts on learning

Classroom behaviour impacts the learning of all students. Maintaining good behaviour in school classrooms is crucial for creating an environment where students can learn and achieve. In classes with positive behaviour, teachers are able to better use their time teaching, and less time reacting to and managing behaviours. This places far less strain on their health and enjoyment of the job, allowing them to teach at their best. For students, better behaviour in classrooms means less disruptions, allowing them to focus on learning.

ERO has looked at the behaviour in classrooms in Aotearoa New Zealand and how this is changing

This evaluation report sets out what ERO has found about behaviour in classrooms and the impact of behaviour on students and teachers. The companion good practice report shares practical strategies for teachers and leaders to support improvements in managing challenging behaviour in their schools.

Key findings

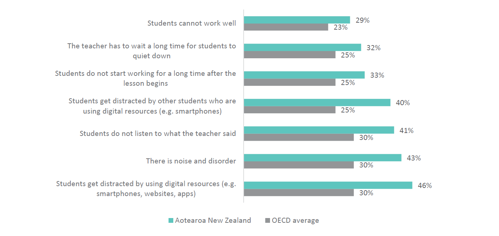

1. Behaviour is a major problem in Aotearoa New Zealand schools, and it is worse than other countries.

-

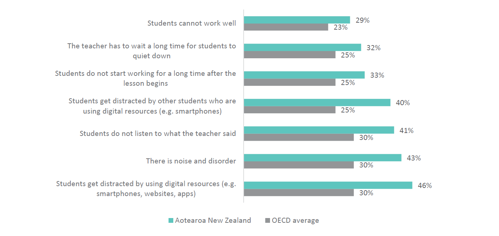

- Half of teachers have to deal with students calling out and distracting others in every lesson.

- A quarter of principals see students physically harming others and damaging or taking property every day.

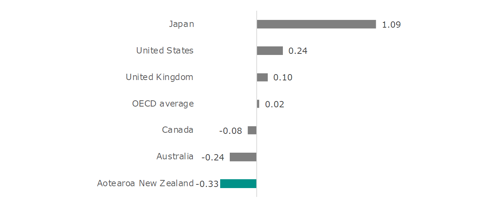

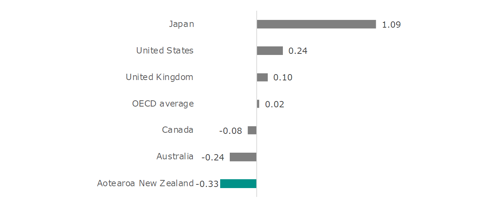

- PISA results over the last 20 years show that Aotearoa New Zealand’s classrooms have consistently had worse behaviour compared to most other OECD countries. For example, Aotearoa New Zealand is lowest among OECD for behaviour in maths classes and in the bottom quarter of PISA countries for behaviour in English classes.

Figure 1: Proportion of students reporting ‘every lesson’ or ‘most lessons’ in maths classes 2022

Figure 2: Index of disciplinary climate in maths class across some OECD countries 2022 (higher numbers are better disciplinary climates, lower numbers are worse disciplinary climates)

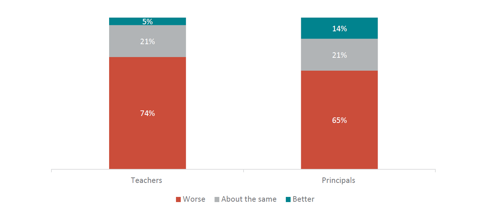

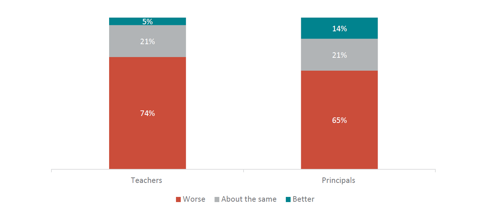

2. Student behaviour has become worse in the last two years.

Over half of teachers report all types of behaviour have become worse. In particular, they report a greater number of students displaying challenging behaviour.

Figure 3: Teachers’ and principals' view of behaviour change overall in the last two years

3. Behaviour is significantly damaging student learning and achievement.

Almost half (47 percent) of teachers spend 40-50 mins a day or more responding to challenging behaviour. This limits the time available to teach.

Three-quarters of teachers believe student behaviour is impacting on students’ progress.

International evidence (PISA) links behaviour and achievement, finding students in the most well-behaved maths classes scored significantly higher than all other students, and students in the worst-behaved classes scored the lowest.

“It could impact us pretty badly… especially around this time. Like for the seniors, especially when we're trying to learn as much as we can for our externals and all that. So, if we miss one bit of information, that may decide if we get a pass or not a pass.” (Student)

4. Behaviour is significantly impacting student enjoyment of school and therefore attendance.

Two-thirds of teachers (68 percent) and principals (63 percent) find that challenging behaviour in the classroom has a large impact on student enjoyment. Enjoyment of school is a key driver of attendance.

“Some kids in my class were not doing their work and being silly and it annoyed me because they were sitting at my desk and they were getting me distracted.” (Student)

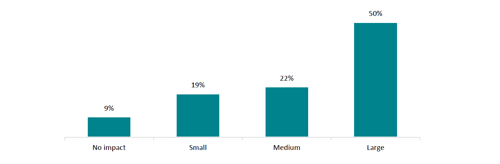

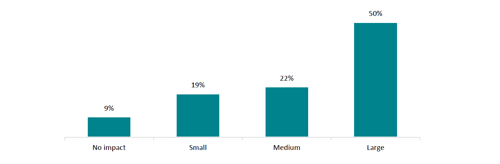

5. Behaviour is a key driver of teachers leaving teaching.

Behaviour impacts on teacher wellbeing through mental health, physical health, and stress.

Half of teachers (50 percent) say this has a large impact on their intention to stay in the profession.

“I think it certainly takes its toll on teacher morale. I think there's a level of frustration for teachers that they are here because they want to do absolutely the best by their students… and they question their practice all the time.” (Principal)

Figure 4: Impact on teachers' intention to stay in the profession: teacher’s view

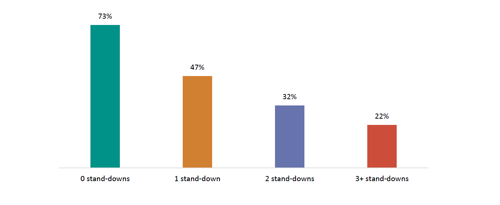

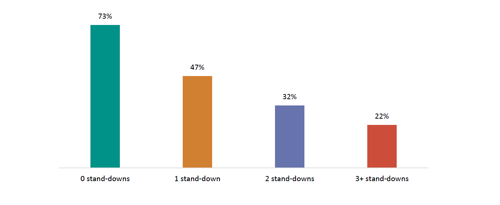

6. Behaviour is associated with negative life outcomes.

Student behaviour is sometimes managed through being stood-down (not allowed to attend school). These students have worse life outcomes.

Students with three or more stand-downs are less than a third as likely to leave school with NCEA Level 2 (22 percent) than those with no stand-downs (73 percent).

Experiencing stand-downs is linked to other longer-term outcomes such as unemployment, offending, and poor health.

The younger a student’s first stand-down, suspension, or exclusion, the more likely they are to receive a benefit, have lower income, have a greater number of admissions to emergency departments, offend, or receive a custodial sentence.

Figure 5: Attainment of NCEA Level 2+ at age 20 by number of stand-downs

7. Behaviour issues are particularly severe in large schools and schools in low socioeconomic communities.

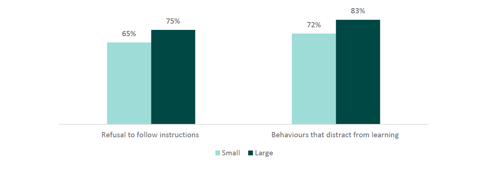

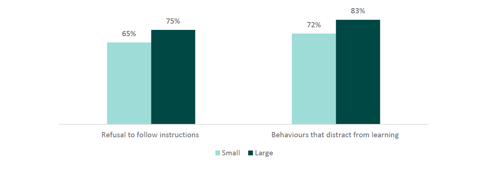

Teachers at larger schools see challenging behaviour more often, such as refusal to follow instructions (75 percent of teachers at large schools see this every day, compared with 65 percent of teachers at small schools).

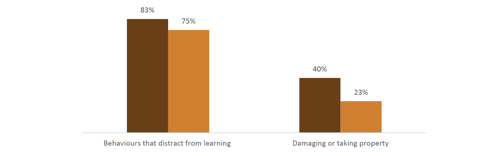

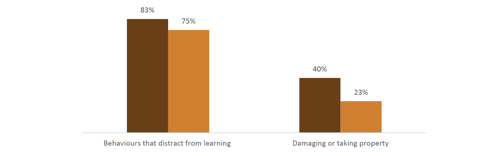

Teachers from schools in low socioeconomic communities also see challenging behaviour more often, such as damaging or taking property (40 percent see this at least every day, compared to 23 percent from schools in high socioeconomic communities), reflecting the additional challenges in these communities.

Figure 6: Percent of teachers seeing behaviours every day or more by school size

Figure 7: Differences across socioeconomic status in percent of teachers seeing behaviours every day or more

8. Teachers are not all well prepared to manage behaviour.

Less than half (45 percent) of new teachers report being capable of managing behaviours in the classroom in their first term.

Older new teachers (aged 36 and above) are more prepared to manage behaviour in their first term teaching then teachers aged 35 or younger.

9. Many teachers and principals struggle to access the expert support they need, particularly in secondary schools and schools in low socioeconomic communities.

Half of teachers (54 percent) and three-quarters of principals (72 percent) find timely advice from experts to be an important support, yet four in 10 (39 percent) teachers and half of principals (49 percent) find it difficult to access.

Teachers at secondary school feel the least supported, and that their behavioural policies and procedures are the least effective and applied the least consistently.

10. Teachers struggle to find the time to respond to behaviour.

Over half of teachers (53 percent) and principals (60 percent) find it difficult to access the time they need to tackle behaviour issues.

“There's a lot more time that is being needed to address all the various issues, and that puts a huge pressure on schools.” (Student support director)

11. There are inconsistencies in behaviour management within schools and between schools.

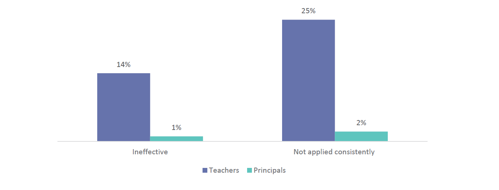

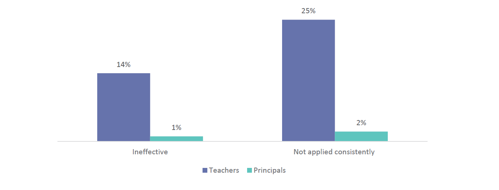

One in four teachers (25 percent) report that their school’s behaviour policies and procedures are not applied consistently at their school. But just 2 percent of principals think they are not applied consistently.

Figure 8: Teachers and principals reporting that their behaviour policies and procedures are ineffective and not applied consistently

1. Behaviour is a major problem in Aotearoa New Zealand schools, and it is worse than other countries.

-

- Half of teachers have to deal with students calling out and distracting others in every lesson.

- A quarter of principals see students physically harming others and damaging or taking property every day.

- PISA results over the last 20 years show that Aotearoa New Zealand’s classrooms have consistently had worse behaviour compared to most other OECD countries. For example, Aotearoa New Zealand is lowest among OECD for behaviour in maths classes and in the bottom quarter of PISA countries for behaviour in English classes.

Figure 1: Proportion of students reporting ‘every lesson’ or ‘most lessons’ in maths classes 2022

Figure 2: Index of disciplinary climate in maths class across some OECD countries 2022 (higher numbers are better disciplinary climates, lower numbers are worse disciplinary climates)

2. Student behaviour has become worse in the last two years.

Over half of teachers report all types of behaviour have become worse. In particular, they report a greater number of students displaying challenging behaviour.

Figure 3: Teachers’ and principals' view of behaviour change overall in the last two years

3. Behaviour is significantly damaging student learning and achievement.

Almost half (47 percent) of teachers spend 40-50 mins a day or more responding to challenging behaviour. This limits the time available to teach.

Three-quarters of teachers believe student behaviour is impacting on students’ progress.

International evidence (PISA) links behaviour and achievement, finding students in the most well-behaved maths classes scored significantly higher than all other students, and students in the worst-behaved classes scored the lowest.

“It could impact us pretty badly… especially around this time. Like for the seniors, especially when we're trying to learn as much as we can for our externals and all that. So, if we miss one bit of information, that may decide if we get a pass or not a pass.” (Student)

4. Behaviour is significantly impacting student enjoyment of school and therefore attendance.

Two-thirds of teachers (68 percent) and principals (63 percent) find that challenging behaviour in the classroom has a large impact on student enjoyment. Enjoyment of school is a key driver of attendance.

“Some kids in my class were not doing their work and being silly and it annoyed me because they were sitting at my desk and they were getting me distracted.” (Student)

5. Behaviour is a key driver of teachers leaving teaching.

Behaviour impacts on teacher wellbeing through mental health, physical health, and stress.

Half of teachers (50 percent) say this has a large impact on their intention to stay in the profession.

“I think it certainly takes its toll on teacher morale. I think there's a level of frustration for teachers that they are here because they want to do absolutely the best by their students… and they question their practice all the time.” (Principal)

Figure 4: Impact on teachers' intention to stay in the profession: teacher’s view

6. Behaviour is associated with negative life outcomes.

Student behaviour is sometimes managed through being stood-down (not allowed to attend school). These students have worse life outcomes.

Students with three or more stand-downs are less than a third as likely to leave school with NCEA Level 2 (22 percent) than those with no stand-downs (73 percent).

Experiencing stand-downs is linked to other longer-term outcomes such as unemployment, offending, and poor health.

The younger a student’s first stand-down, suspension, or exclusion, the more likely they are to receive a benefit, have lower income, have a greater number of admissions to emergency departments, offend, or receive a custodial sentence.

Figure 5: Attainment of NCEA Level 2+ at age 20 by number of stand-downs

7. Behaviour issues are particularly severe in large schools and schools in low socioeconomic communities.

Teachers at larger schools see challenging behaviour more often, such as refusal to follow instructions (75 percent of teachers at large schools see this every day, compared with 65 percent of teachers at small schools).

Teachers from schools in low socioeconomic communities also see challenging behaviour more often, such as damaging or taking property (40 percent see this at least every day, compared to 23 percent from schools in high socioeconomic communities), reflecting the additional challenges in these communities.

Figure 6: Percent of teachers seeing behaviours every day or more by school size

Figure 7: Differences across socioeconomic status in percent of teachers seeing behaviours every day or more

8. Teachers are not all well prepared to manage behaviour.

Less than half (45 percent) of new teachers report being capable of managing behaviours in the classroom in their first term.

Older new teachers (aged 36 and above) are more prepared to manage behaviour in their first term teaching then teachers aged 35 or younger.

9. Many teachers and principals struggle to access the expert support they need, particularly in secondary schools and schools in low socioeconomic communities.

Half of teachers (54 percent) and three-quarters of principals (72 percent) find timely advice from experts to be an important support, yet four in 10 (39 percent) teachers and half of principals (49 percent) find it difficult to access.

Teachers at secondary school feel the least supported, and that their behavioural policies and procedures are the least effective and applied the least consistently.

10. Teachers struggle to find the time to respond to behaviour.

Over half of teachers (53 percent) and principals (60 percent) find it difficult to access the time they need to tackle behaviour issues.

“There's a lot more time that is being needed to address all the various issues, and that puts a huge pressure on schools.” (Student support director)

11. There are inconsistencies in behaviour management within schools and between schools.

One in four teachers (25 percent) report that their school’s behaviour policies and procedures are not applied consistently at their school. But just 2 percent of principals think they are not applied consistently.

Figure 8: Teachers and principals reporting that their behaviour policies and procedures are ineffective and not applied consistently

Evidence-based practice

Effective behaviour management uses a combination of ‘proactive’ and ‘reactive’ strategies.

We reviewed international and local evidence to find the most effective practices for managing challenging behaviour in schools. These evidence-based strategies are a combination of ‘proactive’ (preventing challenging behaviour) and ‘reactive’ (responding to challenging behaviour) approaches.

Table 1: Evidence-based practice areas

|

Proactive |

Practice area 1 |

Know and understand students and what influences their behaviour This involves teachers sourcing information about the range of factors that influence student behaviour. These include past behaviours and incidents, attendance and achievement information, individual needs, and family or wider community contexts. Knowing about these influences equips teachers to understand classroom behaviours and choose effective strategies. |

|

|

Practice area 2 |

Use a consistent approach across the school to prevent and manage challenging behaviour A whole-school approach to behaviour management means all staff and students have shared understandings and clear expectations around behaviour. A whole-school approach includes training on how to implement agreed behaviour management strategies, and careful monitoring across the school through systematically tracking behaviour data. |

|

|

|

Practice area 3 |

Use strategies in the classroom to support expected behaviour Classroom strategies for managing behaviour start with setting high behavioural expectations and clear, logical consequences for challenging behaviour. These are developed and implemented with students, documented, discussed often, and consistently applied. The classroom layout (e.g. seating arrangements, visual displays) aligns with these expectations. |

||

|

Practice area 4 |

Teach learning behaviours alongside managing challenging behaviour This involves explicitly teaching students positive classroom behaviours like listening to instructions, working well with classmates, monitoring their own behaviour, and persisting with classroom tasks. Setting students up with positive learning behaviours reduces the need to manage challenging behaviour. |

||

|

Reactive |

|||

|

Practice area 5 |

Respond effectively to challenging behaviour This involves teachers being confident in a range of effective responses to challenging behaviour. Strategies include clear and immediate feedback to correct minor challenging behaviours like talking at inappropriate times, as well as logical consequences for more serious or recurring behaviours. |

||

|

Practice area 6 |

Use targeted approaches to meet the individual needs of students Targeted approaches are intended for students with the most challenging behaviour. Leaders and teachers work with experts and parents and whānau to plan and implement specific strategies for individual students, that align with the whole-school behaviour management approach. |

Effective behaviour management uses a combination of ‘proactive’ and ‘reactive’ strategies.

We reviewed international and local evidence to find the most effective practices for managing challenging behaviour in schools. These evidence-based strategies are a combination of ‘proactive’ (preventing challenging behaviour) and ‘reactive’ (responding to challenging behaviour) approaches.

Table 1: Evidence-based practice areas

|

Proactive |

Practice area 1 |

Know and understand students and what influences their behaviour This involves teachers sourcing information about the range of factors that influence student behaviour. These include past behaviours and incidents, attendance and achievement information, individual needs, and family or wider community contexts. Knowing about these influences equips teachers to understand classroom behaviours and choose effective strategies. |

|

|

Practice area 2 |

Use a consistent approach across the school to prevent and manage challenging behaviour A whole-school approach to behaviour management means all staff and students have shared understandings and clear expectations around behaviour. A whole-school approach includes training on how to implement agreed behaviour management strategies, and careful monitoring across the school through systematically tracking behaviour data. |

|

|

|

Practice area 3 |

Use strategies in the classroom to support expected behaviour Classroom strategies for managing behaviour start with setting high behavioural expectations and clear, logical consequences for challenging behaviour. These are developed and implemented with students, documented, discussed often, and consistently applied. The classroom layout (e.g. seating arrangements, visual displays) aligns with these expectations. |

||

|

Practice area 4 |

Teach learning behaviours alongside managing challenging behaviour This involves explicitly teaching students positive classroom behaviours like listening to instructions, working well with classmates, monitoring their own behaviour, and persisting with classroom tasks. Setting students up with positive learning behaviours reduces the need to manage challenging behaviour. |

||

|

Reactive |

|||

|

Practice area 5 |

Respond effectively to challenging behaviour This involves teachers being confident in a range of effective responses to challenging behaviour. Strategies include clear and immediate feedback to correct minor challenging behaviours like talking at inappropriate times, as well as logical consequences for more serious or recurring behaviours. |

||

|

Practice area 6 |

Use targeted approaches to meet the individual needs of students Targeted approaches are intended for students with the most challenging behaviour. Leaders and teachers work with experts and parents and whānau to plan and implement specific strategies for individual students, that align with the whole-school behaviour management approach. |

We need to change the trend of worsening behaviour in our classrooms

ERO’s recommendations are:

Cross-cutting: Moving to a national approach.

Recommendation 1: Prioritise classroom behaviour and move to a more national approach to support all schools to prevent, notice, and respond to challenging behaviours effectively. This needs to include a more consistent set of expert supports and programmes for schools, based off a stronger evidence base of what is effective.

Area 1: Increase accountability and set clear expectations

Recommendation 2: ERO to include a sharper focus in its reviews of schools on schools’ behavioural climate, policies, and plans for managing behaviour.

Recommendation 3: Provide national guidance to school boards on clear minimum expectations of the behaviour climate, and for boards to set clear expectations for behaviour across their schools and ensure that these are understood by teachers and parents and whānau.

Area 2: Greater prevention

Recommendation 4: Increase in-school and out-of-school support that identifies and addresses underlying causes of behaviour, e.g. intensive parenting support, access to counselling to reduce anxiety, and support to develop individualised behaviour plans.

Recommendation 5: Examine school size and structures within larger schools – noting that behaviour in large schools is more of a problem than in smaller schools.

Recommendation 6: Support schools to monitor behaviour, identify issues early, and ensure information on prior behaviour is passed between settings (e.g. early learning to schools, primary to secondary).

Recommendation 7: Support schools to adopt evidence-based practices that promote positive behaviour and increase consistency of how behaviour is managed within the school.

Area 3: Raising teachers’ capability

Recommendation 8: Increase the focus on managing behaviour as part of Initial Teacher Education (building on the practice of the Initial Teacher Education providers who do this well) and within the first two years of induction of beginning teachers, and within the Teaching Standards (Teaching Council).

Recommendation 9: Increase recruitment of more mature Initial Teacher Education students who are better able to manage behaviour.

Recommendation 10: Prioritise evidence-based professional learning and development for teachers on effective approaches to managing behaviour and consider nationally accredited professional learning and development.

Area 4: Greater investment in effective support

Recommendation 11: Increase availability of specialist support for students (e.g. educational psychologists, this will require increasing supply).

Recommendation 12: Identify and grow the most effective (and value for money) supports and programmes and embed these consistently in all schools, including evaluating the effectiveness of current programmes (such as Positive Behaviour for Learning).

Recommendation 13: Review the learning support workforce and funding models to ensure schools and teachers can access the right supports at the right time.

Recommendation 14: Prioritise support for schools with the largest behavioural issues, including larger schools and schools in low socioeconomic communities.

Area 5: Effective consequences

Recommendation 15: Provide clear guidance to schools on what the most effective consequences for challenging behaviour are and how to use them to achieve the best outcomes for students.

Recommendation 16: Ensure suspensions remain a last resort and that they trigger individual behaviour plans and the support needed for successful changes of behaviour.

ERO’s recommendations are:

Cross-cutting: Moving to a national approach.

Recommendation 1: Prioritise classroom behaviour and move to a more national approach to support all schools to prevent, notice, and respond to challenging behaviours effectively. This needs to include a more consistent set of expert supports and programmes for schools, based off a stronger evidence base of what is effective.

Area 1: Increase accountability and set clear expectations

Recommendation 2: ERO to include a sharper focus in its reviews of schools on schools’ behavioural climate, policies, and plans for managing behaviour.

Recommendation 3: Provide national guidance to school boards on clear minimum expectations of the behaviour climate, and for boards to set clear expectations for behaviour across their schools and ensure that these are understood by teachers and parents and whānau.

Area 2: Greater prevention

Recommendation 4: Increase in-school and out-of-school support that identifies and addresses underlying causes of behaviour, e.g. intensive parenting support, access to counselling to reduce anxiety, and support to develop individualised behaviour plans.

Recommendation 5: Examine school size and structures within larger schools – noting that behaviour in large schools is more of a problem than in smaller schools.

Recommendation 6: Support schools to monitor behaviour, identify issues early, and ensure information on prior behaviour is passed between settings (e.g. early learning to schools, primary to secondary).

Recommendation 7: Support schools to adopt evidence-based practices that promote positive behaviour and increase consistency of how behaviour is managed within the school.

Area 3: Raising teachers’ capability

Recommendation 8: Increase the focus on managing behaviour as part of Initial Teacher Education (building on the practice of the Initial Teacher Education providers who do this well) and within the first two years of induction of beginning teachers, and within the Teaching Standards (Teaching Council).

Recommendation 9: Increase recruitment of more mature Initial Teacher Education students who are better able to manage behaviour.

Recommendation 10: Prioritise evidence-based professional learning and development for teachers on effective approaches to managing behaviour and consider nationally accredited professional learning and development.

Area 4: Greater investment in effective support

Recommendation 11: Increase availability of specialist support for students (e.g. educational psychologists, this will require increasing supply).

Recommendation 12: Identify and grow the most effective (and value for money) supports and programmes and embed these consistently in all schools, including evaluating the effectiveness of current programmes (such as Positive Behaviour for Learning).

Recommendation 13: Review the learning support workforce and funding models to ensure schools and teachers can access the right supports at the right time.

Recommendation 14: Prioritise support for schools with the largest behavioural issues, including larger schools and schools in low socioeconomic communities.

Area 5: Effective consequences

Recommendation 15: Provide clear guidance to schools on what the most effective consequences for challenging behaviour are and how to use them to achieve the best outcomes for students.

Recommendation 16: Ensure suspensions remain a last resort and that they trigger individual behaviour plans and the support needed for successful changes of behaviour.

What next?

To find out more about behaviour in Aotearoa New Zealand classrooms, and good practice and support strategies for managing classroom behaviour, check out our main evaluation report, good practice report, and practical guides for leaders, teachers, and school boards. These can be downloaded for free from ERO’s Evidence and Insights website, www.evidence.ero.govt.nz. These resources have been designed to be practical and useful, to help schools with manageable shifts in practice that will make a real difference for students and staff.

ERO’s suite of classroom behaviour evaluation, practice and support resources

|

Link |

What’s it about? |

Who is it for? |

|

Time to Focus: Behaviour in our Classrooms |

The evaluation report shares what ERO found out about the behaviours happening in our classrooms. |

Teachers, leaders, parents and whānau, learning support staff, specialists, and the wider education sector |

|

Good Practice: Behaviour in our Classrooms |

The good practice report sets out how schools can manage classroom behaviour. |

Teachers, leaders, parents and whānau, learning support staff, specialists, and the wider education sector |

|

Guide for Teachers: Behaviour in our Classrooms |

This guide sets out practical actions for teachers. |

Primary and secondary school teachers |

|

Guide for School Leaders: Behaviour in our Classrooms |

This guide sets out practical actions for school leaders. |

Principals, and other school leaders at primary and secondary schools |

|

Insights for School Boards: Behaviour in our Classrooms |

This brief guide for school boards explains how they can help their school focus on behaviour. |

Board members at primary and secondary schools |

What ERO did

Data collected for this report included:

- surveys of 1557 teachers

- surveys of 547 principals

- focus groups with:

- school staff

- students

- parents and whānau

- Resource Teachers: Learning and Behaviour (RTLBs) from two clusters

- site visits and online sessions with 10 schools

- an in-depth review of literature, including Education Endowment Foundation research

- Ministry of Education statistics on the frequency of stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions and, expulsions

- data from the Integrated Data Infrastructure describing outcomes of people who experienced stand-downs, suspensions, and exclusions, analysed by The Social Wellbeing Agency.

We appreciate the work of all those who supported this research, particularly the teachers, school leaders, students, parents and whānau, and experts who shared with us. Their experiences and insights are at the heart of what we have learnt.

To find out more about behaviour in Aotearoa New Zealand classrooms, and good practice and support strategies for managing classroom behaviour, check out our main evaluation report, good practice report, and practical guides for leaders, teachers, and school boards. These can be downloaded for free from ERO’s Evidence and Insights website, www.evidence.ero.govt.nz. These resources have been designed to be practical and useful, to help schools with manageable shifts in practice that will make a real difference for students and staff.

ERO’s suite of classroom behaviour evaluation, practice and support resources

|

Link |

What’s it about? |

Who is it for? |

|

Time to Focus: Behaviour in our Classrooms |

The evaluation report shares what ERO found out about the behaviours happening in our classrooms. |

Teachers, leaders, parents and whānau, learning support staff, specialists, and the wider education sector |

|

Good Practice: Behaviour in our Classrooms |

The good practice report sets out how schools can manage classroom behaviour. |

Teachers, leaders, parents and whānau, learning support staff, specialists, and the wider education sector |

|

Guide for Teachers: Behaviour in our Classrooms |

This guide sets out practical actions for teachers. |

Primary and secondary school teachers |

|

Guide for School Leaders: Behaviour in our Classrooms |

This guide sets out practical actions for school leaders. |

Principals, and other school leaders at primary and secondary schools |

|

Insights for School Boards: Behaviour in our Classrooms |

This brief guide for school boards explains how they can help their school focus on behaviour. |

Board members at primary and secondary schools |

What ERO did

Data collected for this report included:

- surveys of 1557 teachers

- surveys of 547 principals

- focus groups with:

- school staff

- students

- parents and whānau

- Resource Teachers: Learning and Behaviour (RTLBs) from two clusters

- site visits and online sessions with 10 schools

- an in-depth review of literature, including Education Endowment Foundation research

- Ministry of Education statistics on the frequency of stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions and, expulsions

- data from the Integrated Data Infrastructure describing outcomes of people who experienced stand-downs, suspensions, and exclusions, analysed by The Social Wellbeing Agency.

We appreciate the work of all those who supported this research, particularly the teachers, school leaders, students, parents and whānau, and experts who shared with us. Their experiences and insights are at the heart of what we have learnt.