What is it?

Oral language interventions (also known as oracy or speaking and listening interventions) refer to approaches that emphasise the importance of spoken language and verbal interaction in the classroom. They include dialogic activities.

Oral language interventions are based on the idea that comprehension and reading skills benefit from explicit discussion of either content or processes of learning, or both, oral language interventions aim to support students’ use of vocabulary, articulation of ideas and spoken expression.

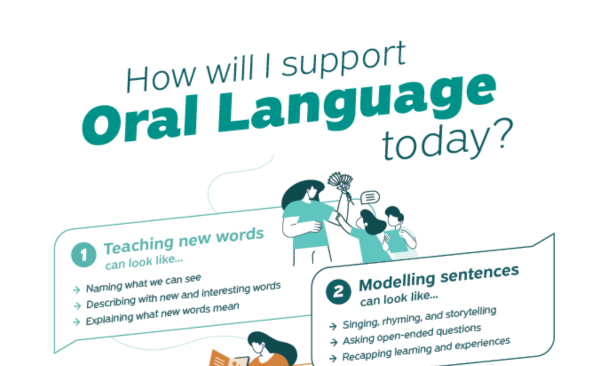

Oral language approaches might include:

- targeted reading aloud and book discussion with young children;

- explicitly extending students’ spoken vocabulary;

- the use of structured questioning to develop reading comprehension; and

- the use of purposeful, curriculum-focused, dialogue and interaction.

Oral language interventions have some similarity to approaches based on Metacognition (which make talk about learning explicit in classrooms), and to Collaborative learning approaches which promote students’ interaction in groups.

When considering oral language interventions, schools should also consider and respond to the diversity of languages represented in the school (for example, home or heritage languages), and how this might influence their intervention strategies.

Research report | 60 min read

Research report | 60 min read Good practice report | 30 min read

Good practice report | 30 min read Research summary | 5 min read

Research summary | 5 min read Good practice guide | 10 min read

Good practice guide | 10 min read Good practice guide | 10 min read

Good practice guide | 10 min read Sector insights | 5 min read

Sector insights | 5 min read Sector insights | 5 min read

Sector insights | 5 min read Good practice guide | 1 min read

Good practice guide | 1 min read Good practice guide | 0 min read

Good practice guide | 0 min read