Related insights

Explore related documents that might be interested in.

Read Online

Executive summary

Chronic absence has doubled in the last decade. Last term over 80,000 students missed more than three weeks of school. These chronically absent students (at school 70 percent or less of the time) are often struggling and are at high risk of poor education and lifetime outcomes. The Education Review office (ERO) looked at how good the education system and supports are for chronic absence in Aotearoa New Zealand and found that we do not have a strong enough system or effective supports to address chronic absence.

Attendance is crucial for learning and thriving at school. Students are expected to be in school learning every day. If a student misses more than 30 percent of school a term then they are chronically absent. This means they are missing more than three days a fortnight.

Key findings

What has happened to chronic absence rates in Aotearoa New Zealand?

Finding 1: Aotearoa New Zealand is experiencing a crisis of chronic absence. Chronic absence doubled from 2015 to 2023 and is now 10 percent.

One in 10 students (10 percent) were chronically absent in Term 2, 2024. Chronic absence rates have doubled in secondary schools, and nearly tripled in primary schools since 2015.

Why do students become chronically absent?

Finding 2: There is a range of risk factors that make it more likely a student will be chronically absent. The most predictive factors are previous poor attendance, offending, and being in social or emergency housing.

Students who are chronically absent are:

- five times more likely to be chronically absent if they were chronically absent in the previous year - 25 percent of students who are chronically absent were chronically absent a year ago

- four times as likely to have a recent history of offending - 4 percent of students who are chronically absent have a recent history of offending (compared to less than 1 percent of all students)

- four times as likely to live in social housing - just over one in 10 (12 percent) of chronically absent students live in social housing, compared to 3 percent of all students.

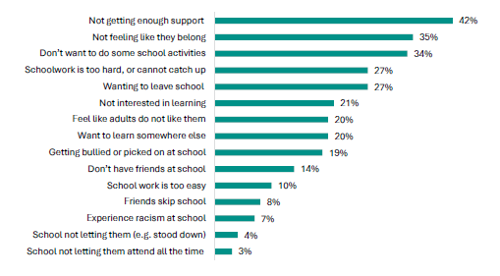

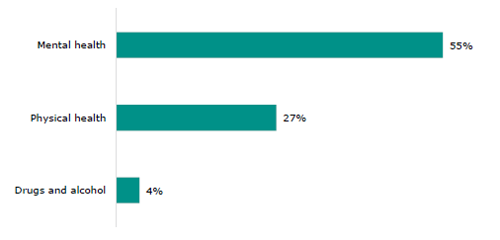

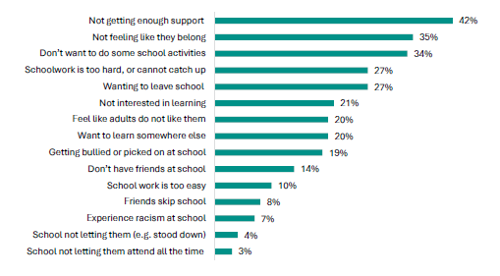

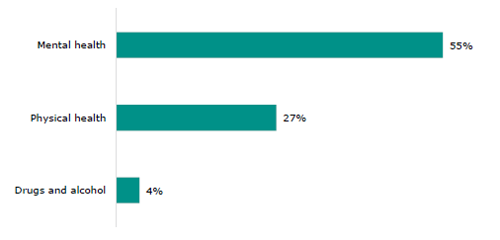

Finding 3: Students’ attitudes to school and challenges they face are drivers of chronic absence. Wanting to leave school, physical health issues, finding it hard to get up in the morning, and mental health issues are key drivers.

Nearly a quarter of students who are chronically absent report wanting to leave school as a reason for being absent. Over half (55 percent) identified mental health and a quarter (27 percent) identified physical health as reasons for being chronically absent.

What happens to students who have been chronically absent?

Finding 4: Attendance matters. Students who were chronically absent are significantly more likely to leave school without qualifications and then, when they are adults, they are more likely to be charged with an offence, or live in social or emergency housing.

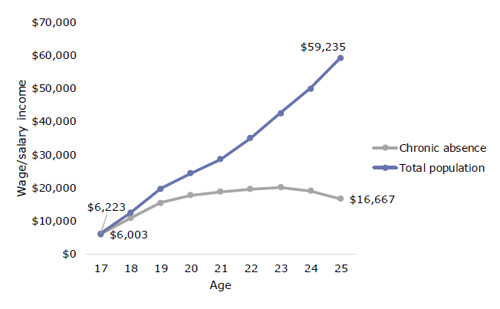

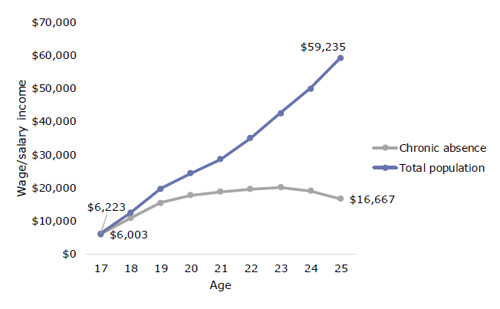

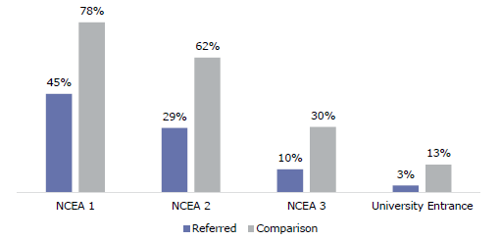

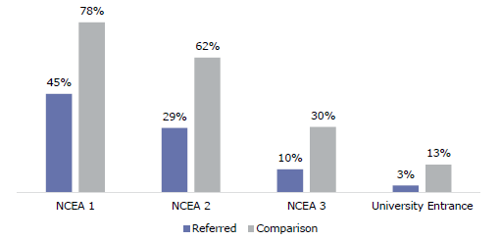

Attendance is critical for life outcomes; students with chronic absence have worse outcomes. At age 20, over half (55 percent) have not achieved NCEA Level 2, and almost all (92 percent) have not achieved University Entrance. This leads to having significantly worse employment outcomes. At age 25, nearly half are not earning wages and almost half are receiving a benefit.

Finding 5: Chronically absent young people cost the Government nearly three times as much.

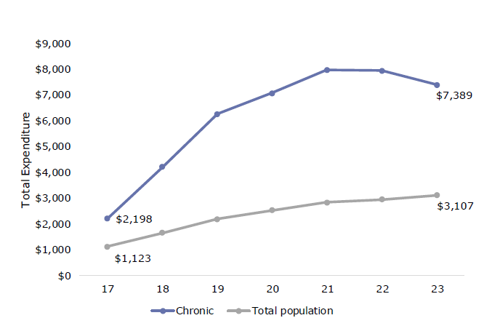

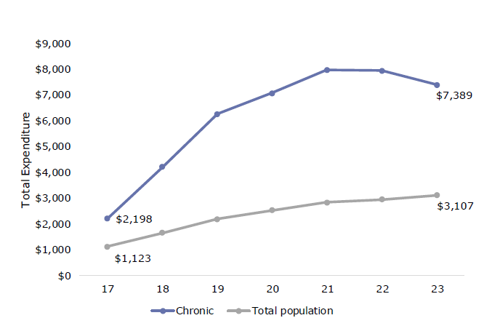

We know that being chronically absent has large individual costs in terms of income, health, and social outcomes. The poor outcomes of young adults who were chronically absent from school also pose a sizeable cost to the Government. At age 23, young adults who were chronically absent cost $4,000 more than other young people. They are particularly costly in corrections, hospital admissions, and receiving benefits.

What works to address chronic absence?

Finding 6: Reducing chronic absence requires both good prevention and an effective system for addressing it.

The evidence is clear about the key components of an effective system for addressing chronic absence.

- There are clear expectations for attendance, and everyone knows what these are.

- There is a clear definition of what ‘poor attendance’ is, students are identified as their attendance starts to decline, and action is taken early to address their attendance.

- Students who are persistently absent from school are found, and they and their parents are engaged.

- The students, parents and whānau, schools, and other services develop a plan to get the students to attend school regularly.

- The barriers to attendance are removed, and compliance with the plan by students, parents and whānau, schools, and other parties is enforced.

- The student is returned to regularly attending school, and additional supports are scaled back.

- Schools monitor attendance, any issues are immediately acted on, and students receive the education and support that meets their needs.

- There are clear roles and responsibilities for improving attendance. Accountability across the roles is clear, and the functions are adequately resourced.

How good is the education system at addressing chronic absence?

Finding 7: ERO’s review has found weaknesses in each element of the system.

To understand how effective the model for attendance in Aotearoa New Zealand is, we compared the current practice with the key components of an effective system and found weaknesses in each element.

a) Schools are setting expectations for attendance, but parents do not understand the implications of non-attendance.

When students, and parents and whānau do not understand the implications of absence, chronic absence rates increase from 7 percent to 9 percent.

b) Action is too slow, and students fall through the gaps.

Schools have tools in place to identify when students are chronically absent, but often wait too long to intervene. Only 43 percent of parents and whānau with a child who is chronically absent have met with school staff about their child’s attendance. One in five school leaders (18 percent) only refer students after more than 21 consecutive days absent. Just over two-thirds of Attendance Service staff report schools never, or only sometimes, refer students at the right time (68 percent). Approximately half of schools do not make referrals to Attendance Services.

c) Finding students who are not attending is inefficient and time consuming.

There is inadequate information sharing between different agencies, schools, and Attendance Services. Attendance Services have to spend too much time trying to find students. Almost half of Attendance Services (52 percent) report information is only sometimes, or never shared, across agencies, schools, and Attendance Services.

d) Schools and Attendance Services are not well set up to enforce attendance.

Just over half of school leaders (54 percent) and just over three in five Attendance Service staff (62 percent) do not think there are good options to enforce attendance and hold people accountable. Schools that have tried to prosecute have found the process complex and costly.

e) Students are not set up to succeed on return to school.

The quality of plans for returning students to school is variable, and students are not set up to succeed on return to school. While many schools welcome students back to school, there is not a sufficient focus on working with the students to help them ‘catch up’ and reintegrate.

f) Improvements in school attendance are often short-lived as barriers remain. The education on offer often does not meet students’ needs, so attendance is not sustained.

Attendance rates improve over the two months after referral to the Attendance Service, but six months after referral students remain, on average, chronically absent (attending only 62 percent of the time).

Although nearly four in five students who are chronically absent (79 percent) find learning at school a barrier to their attendance, but under half (44 percent) of school leaders report they have changed schoolwork to better suit students on their return. Over half of school leaders (59 percent) and Attendance Services (58 percent) report there are not opportunities for young people to learn in other settings.

g) Accountability in the system is weak.

There is a lack of clarity around where roles and responsibilities begin and end. Just over one in five school leaders (21 percent) and two in five Attendance Service providers (40 percent) want more clarity about the roles and responsibilities.

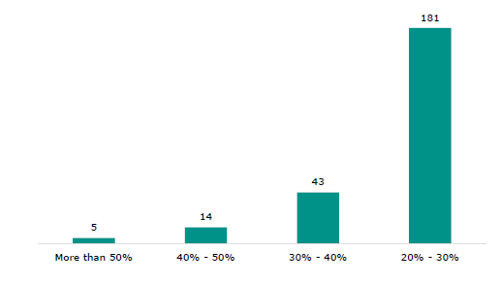

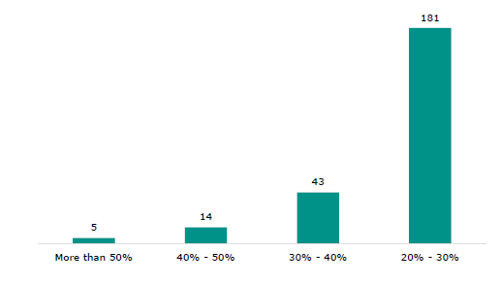

h) Resourcing is inequitably distributed and does not match the level of need.

Funding has not increased to match the increase in demand. Caseloads for advisers in the Attendance Services that ERO visited vary from 30 to more than 500 cases. Funding does not reflect need. Contracts vary in size (from around $20,000 to $1.4m) and in how much funding is allocated per eligible student – from $61 to $1,160 per eligible student.

Finding 8: The model does not set up Attendance Services to succeed and is not delivering outcomes.

The contracting model leads to wide variation in the delivery of services. There is no agreed operating model or consistent guidance on effective practice and the funding is inadequate for the current level of need.

- Attendance Service staff are exceptionally passionate and dedicated to improving student outcomes but this alone is not enough to achieve good outcomes.

- Attendance Services are not leading to sustained improvements in attendance in the long-term. Only two in five students who were supported by an Attendance Service (41 percent) agreed that Attendance Service staff helped them go to school more.

- Attendance Services do not consistently have strong relationships with schools - only half of schools and Attendance Services meet regularly to share information about students (48 percent).

- Attendance Services are not always able to act quickly with their initial engagement in a case - only 50 percent always act quickly when they receive a referral.

- Despite being confident in their knowledge and skills, Attendance Service staff are not consistently drawing from an evidence-base to remove barriers.

- Attendance Services work with a range of agencies, but they do not fully understand others' roles and get drawn away from attendance into providing other support.

Lifetime outcomes for students who are referred to Attendance Services are poor. Students who are referred to Attendance Services have consistently worse life-time outcomes than students with the same characteristics who were never referred to an Attendance Service. This may be due to unobserved factors (e.g., attitudes to education or bullying), but it does show that Attendance Services are not overcoming these barriers.

Finding 9: Schools play a critical role and need to be supported to do more to prevent chronic absence, coordinate with Attendance Services, and then support students return to sustained attendance.

a) Some schools have exceptionally poor attendance.

Only 22 schools make up 10 percent of the total chronic absence nationally.

b) Schools in lower socio-economic areas and secondary schools have greater challenges and higher levels of chronic absence.

Students in schools in lower socio-economic areas are six times more likely to be chronically absent.

c) Not all schools in low socio-economic communities have high rates of chronic absence.

There are 95 schools in low socio-economic communities with less than a 10 percent rate of chronic absence.

d) Schools that are successful at reducing chronic absence do three things.

- They work in close coordination with Attendance Services.

- They do what they are responsible for.

- They hold students, parents and whānau, and Attendance Service staff accountable.

e) When schools do not manage chronic absence well, there are key themes.

- They do not escalate early enough when students are showing signs of increased non-attendance and do not share information with Attendance Services.

- They do not identify the same barriers to attendance that students themselves identify, or work with the Attendance Service providers to coordinate responses and stay connected.

Recommendations

To reduce chronic absence, we need an end-to-end effective system and supports. Our current system for addressing chronic absence does not deliver this. We need to transform the system by building stronger functions (what happens) and reforming the model (how it happens).

1. We need to strengthen how we prevent students becoming chronically absent

Strengthening how we prevent students becoming chronically absent will require social agencies to address the barriers to attendance that sit outside of the education sector.

|

Who |

Action |

|

Agencies |

Government agencies prioritise education and school attendance and take all possible action to address the largest risk factors for chronic absence, which could include:

|

|

Schools, and parents and whānau |

Take all possible steps to support the habit of regular attendance, including acting early when attendance issues arise. |

|

Schools and Ministry of Education |

Schools have planned responses for different levels of non-attendance, with guidance provided by the Ministry of Education on what is effective for returning students to regular attendance. |

|

Schools |

Find and act on learning needs quickly, so that students remain engaged. Address bullying and social isolation, so that students are safe and connected. Provide access to school-based counselling services to address mental health needs. |

|

All |

Increase understanding of the importance of attendance, providing focused messages for parents and whānau of students most at risk of chronic absence. |

|

Schools and agencies |

Identify earlier students with attendance issues, through higher quality recording of attendance, data sharing between agencies who come in contact with them/their parents and whānau and acting to prevent chronic absence. |

2. We need to have effective targeted supports in place to address chronic absence

|

Who |

Action |

|

All |

Put in place clearer roles and responsibilities for chronic absence (for schools, Attendance Services, parents and whānau, and other agencies). |

|

Ministry of Education and ERO |

Use their roles and powers to identify, report, and intervene in schools with high levels of chronic absence. |

|

Schools, Ministry of Education, and agencies |

Increase use of enforcement measures with parents and whānau, including more consistent prosecutions, wider agencies more actively using attendance obligations, and learning from other countries’ models (including those who tie qualification attainment to minimum attendance). |

|

Services |

Ensure that there are expert, dedicated people working with the chronically absent students and their parents and whānau, using the evidence-based key practices that work, including:

|

|

Schools |

Work with services to address chronic absence, including:

|

3. We need to increase the focus on retaining students on their return

|

Who |

Action |

|

Schools |

Put in place a deliberate plan to support returning students to reintegrate, be safe, and catch up. |

|

Schools |

Actively monitor attendance of students who have previously been chronically absent and act early if their attendance declines. |

|

Ministry of Education and schools |

Increase the availability of high-quality vocational and alternative education (either in schools or through secondary-tertiary pathways), building on effective examples of flexible learning and tailored programmes from here and abroad. |

4. We need to put in place an efficient and effective model

|

Where |

Action |

|

Centralise |

Centralise key functions that can be more effectively and efficiently provided nationally, including:

|

|

Localise |

Make sure schools have the resources and the support they need to carry out the functions that most effectively happen locally, including:

Consider giving schools/clusters of schools the responsibility, accountability, and funding for the delivery of the key function of working with chronically absent students and their families, to address education barriers, while drawing on the support of the centralised function to address broader social barriers. |

|

Funding |

Increase funding for those responsible for finding students and returning them to school, reflecting that chronic absence rates have doubled since 2015. Reform how funding is allocated to ensure it matches need. |

Conclusion

ERO found that the number of students who are chronically absent from school is at crisis point, and it is affecting students’ lives. Students who have a history of chronic absence are unlikely to achieve NCEA, have higher rates of offending, are more likely to be victims of crime, and are more likely to be living in social and emergency housing. By age 20, they cost the Government almost three times as much as students who go to school.

The system that is set up to get these students back to school is not effective. It needs substantial reform, and it will take parents and whānau, schools, and Government agencies all working together to fix it and get chronically absent students back to school.

Chronic absence has doubled in the last decade. Last term over 80,000 students missed more than three weeks of school. These chronically absent students (at school 70 percent or less of the time) are often struggling and are at high risk of poor education and lifetime outcomes. The Education Review office (ERO) looked at how good the education system and supports are for chronic absence in Aotearoa New Zealand and found that we do not have a strong enough system or effective supports to address chronic absence.

Attendance is crucial for learning and thriving at school. Students are expected to be in school learning every day. If a student misses more than 30 percent of school a term then they are chronically absent. This means they are missing more than three days a fortnight.

Key findings

What has happened to chronic absence rates in Aotearoa New Zealand?

Finding 1: Aotearoa New Zealand is experiencing a crisis of chronic absence. Chronic absence doubled from 2015 to 2023 and is now 10 percent.

One in 10 students (10 percent) were chronically absent in Term 2, 2024. Chronic absence rates have doubled in secondary schools, and nearly tripled in primary schools since 2015.

Why do students become chronically absent?

Finding 2: There is a range of risk factors that make it more likely a student will be chronically absent. The most predictive factors are previous poor attendance, offending, and being in social or emergency housing.

Students who are chronically absent are:

- five times more likely to be chronically absent if they were chronically absent in the previous year - 25 percent of students who are chronically absent were chronically absent a year ago

- four times as likely to have a recent history of offending - 4 percent of students who are chronically absent have a recent history of offending (compared to less than 1 percent of all students)

- four times as likely to live in social housing - just over one in 10 (12 percent) of chronically absent students live in social housing, compared to 3 percent of all students.

Finding 3: Students’ attitudes to school and challenges they face are drivers of chronic absence. Wanting to leave school, physical health issues, finding it hard to get up in the morning, and mental health issues are key drivers.

Nearly a quarter of students who are chronically absent report wanting to leave school as a reason for being absent. Over half (55 percent) identified mental health and a quarter (27 percent) identified physical health as reasons for being chronically absent.

What happens to students who have been chronically absent?

Finding 4: Attendance matters. Students who were chronically absent are significantly more likely to leave school without qualifications and then, when they are adults, they are more likely to be charged with an offence, or live in social or emergency housing.

Attendance is critical for life outcomes; students with chronic absence have worse outcomes. At age 20, over half (55 percent) have not achieved NCEA Level 2, and almost all (92 percent) have not achieved University Entrance. This leads to having significantly worse employment outcomes. At age 25, nearly half are not earning wages and almost half are receiving a benefit.

Finding 5: Chronically absent young people cost the Government nearly three times as much.

We know that being chronically absent has large individual costs in terms of income, health, and social outcomes. The poor outcomes of young adults who were chronically absent from school also pose a sizeable cost to the Government. At age 23, young adults who were chronically absent cost $4,000 more than other young people. They are particularly costly in corrections, hospital admissions, and receiving benefits.

What works to address chronic absence?

Finding 6: Reducing chronic absence requires both good prevention and an effective system for addressing it.

The evidence is clear about the key components of an effective system for addressing chronic absence.

- There are clear expectations for attendance, and everyone knows what these are.

- There is a clear definition of what ‘poor attendance’ is, students are identified as their attendance starts to decline, and action is taken early to address their attendance.

- Students who are persistently absent from school are found, and they and their parents are engaged.

- The students, parents and whānau, schools, and other services develop a plan to get the students to attend school regularly.

- The barriers to attendance are removed, and compliance with the plan by students, parents and whānau, schools, and other parties is enforced.

- The student is returned to regularly attending school, and additional supports are scaled back.

- Schools monitor attendance, any issues are immediately acted on, and students receive the education and support that meets their needs.

- There are clear roles and responsibilities for improving attendance. Accountability across the roles is clear, and the functions are adequately resourced.

How good is the education system at addressing chronic absence?

Finding 7: ERO’s review has found weaknesses in each element of the system.

To understand how effective the model for attendance in Aotearoa New Zealand is, we compared the current practice with the key components of an effective system and found weaknesses in each element.

a) Schools are setting expectations for attendance, but parents do not understand the implications of non-attendance.

When students, and parents and whānau do not understand the implications of absence, chronic absence rates increase from 7 percent to 9 percent.

b) Action is too slow, and students fall through the gaps.

Schools have tools in place to identify when students are chronically absent, but often wait too long to intervene. Only 43 percent of parents and whānau with a child who is chronically absent have met with school staff about their child’s attendance. One in five school leaders (18 percent) only refer students after more than 21 consecutive days absent. Just over two-thirds of Attendance Service staff report schools never, or only sometimes, refer students at the right time (68 percent). Approximately half of schools do not make referrals to Attendance Services.

c) Finding students who are not attending is inefficient and time consuming.

There is inadequate information sharing between different agencies, schools, and Attendance Services. Attendance Services have to spend too much time trying to find students. Almost half of Attendance Services (52 percent) report information is only sometimes, or never shared, across agencies, schools, and Attendance Services.

d) Schools and Attendance Services are not well set up to enforce attendance.

Just over half of school leaders (54 percent) and just over three in five Attendance Service staff (62 percent) do not think there are good options to enforce attendance and hold people accountable. Schools that have tried to prosecute have found the process complex and costly.

e) Students are not set up to succeed on return to school.

The quality of plans for returning students to school is variable, and students are not set up to succeed on return to school. While many schools welcome students back to school, there is not a sufficient focus on working with the students to help them ‘catch up’ and reintegrate.

f) Improvements in school attendance are often short-lived as barriers remain. The education on offer often does not meet students’ needs, so attendance is not sustained.

Attendance rates improve over the two months after referral to the Attendance Service, but six months after referral students remain, on average, chronically absent (attending only 62 percent of the time).

Although nearly four in five students who are chronically absent (79 percent) find learning at school a barrier to their attendance, but under half (44 percent) of school leaders report they have changed schoolwork to better suit students on their return. Over half of school leaders (59 percent) and Attendance Services (58 percent) report there are not opportunities for young people to learn in other settings.

g) Accountability in the system is weak.

There is a lack of clarity around where roles and responsibilities begin and end. Just over one in five school leaders (21 percent) and two in five Attendance Service providers (40 percent) want more clarity about the roles and responsibilities.

h) Resourcing is inequitably distributed and does not match the level of need.

Funding has not increased to match the increase in demand. Caseloads for advisers in the Attendance Services that ERO visited vary from 30 to more than 500 cases. Funding does not reflect need. Contracts vary in size (from around $20,000 to $1.4m) and in how much funding is allocated per eligible student – from $61 to $1,160 per eligible student.

Finding 8: The model does not set up Attendance Services to succeed and is not delivering outcomes.

The contracting model leads to wide variation in the delivery of services. There is no agreed operating model or consistent guidance on effective practice and the funding is inadequate for the current level of need.

- Attendance Service staff are exceptionally passionate and dedicated to improving student outcomes but this alone is not enough to achieve good outcomes.

- Attendance Services are not leading to sustained improvements in attendance in the long-term. Only two in five students who were supported by an Attendance Service (41 percent) agreed that Attendance Service staff helped them go to school more.

- Attendance Services do not consistently have strong relationships with schools - only half of schools and Attendance Services meet regularly to share information about students (48 percent).

- Attendance Services are not always able to act quickly with their initial engagement in a case - only 50 percent always act quickly when they receive a referral.

- Despite being confident in their knowledge and skills, Attendance Service staff are not consistently drawing from an evidence-base to remove barriers.

- Attendance Services work with a range of agencies, but they do not fully understand others' roles and get drawn away from attendance into providing other support.

Lifetime outcomes for students who are referred to Attendance Services are poor. Students who are referred to Attendance Services have consistently worse life-time outcomes than students with the same characteristics who were never referred to an Attendance Service. This may be due to unobserved factors (e.g., attitudes to education or bullying), but it does show that Attendance Services are not overcoming these barriers.

Finding 9: Schools play a critical role and need to be supported to do more to prevent chronic absence, coordinate with Attendance Services, and then support students return to sustained attendance.

a) Some schools have exceptionally poor attendance.

Only 22 schools make up 10 percent of the total chronic absence nationally.

b) Schools in lower socio-economic areas and secondary schools have greater challenges and higher levels of chronic absence.

Students in schools in lower socio-economic areas are six times more likely to be chronically absent.

c) Not all schools in low socio-economic communities have high rates of chronic absence.

There are 95 schools in low socio-economic communities with less than a 10 percent rate of chronic absence.

d) Schools that are successful at reducing chronic absence do three things.

- They work in close coordination with Attendance Services.

- They do what they are responsible for.

- They hold students, parents and whānau, and Attendance Service staff accountable.

e) When schools do not manage chronic absence well, there are key themes.

- They do not escalate early enough when students are showing signs of increased non-attendance and do not share information with Attendance Services.

- They do not identify the same barriers to attendance that students themselves identify, or work with the Attendance Service providers to coordinate responses and stay connected.

Recommendations

To reduce chronic absence, we need an end-to-end effective system and supports. Our current system for addressing chronic absence does not deliver this. We need to transform the system by building stronger functions (what happens) and reforming the model (how it happens).

1. We need to strengthen how we prevent students becoming chronically absent

Strengthening how we prevent students becoming chronically absent will require social agencies to address the barriers to attendance that sit outside of the education sector.

|

Who |

Action |

|

Agencies |

Government agencies prioritise education and school attendance and take all possible action to address the largest risk factors for chronic absence, which could include:

|

|

Schools, and parents and whānau |

Take all possible steps to support the habit of regular attendance, including acting early when attendance issues arise. |

|

Schools and Ministry of Education |

Schools have planned responses for different levels of non-attendance, with guidance provided by the Ministry of Education on what is effective for returning students to regular attendance. |

|

Schools |

Find and act on learning needs quickly, so that students remain engaged. Address bullying and social isolation, so that students are safe and connected. Provide access to school-based counselling services to address mental health needs. |

|

All |

Increase understanding of the importance of attendance, providing focused messages for parents and whānau of students most at risk of chronic absence. |

|

Schools and agencies |

Identify earlier students with attendance issues, through higher quality recording of attendance, data sharing between agencies who come in contact with them/their parents and whānau and acting to prevent chronic absence. |

2. We need to have effective targeted supports in place to address chronic absence

|

Who |

Action |

|

All |

Put in place clearer roles and responsibilities for chronic absence (for schools, Attendance Services, parents and whānau, and other agencies). |

|

Ministry of Education and ERO |

Use their roles and powers to identify, report, and intervene in schools with high levels of chronic absence. |

|

Schools, Ministry of Education, and agencies |

Increase use of enforcement measures with parents and whānau, including more consistent prosecutions, wider agencies more actively using attendance obligations, and learning from other countries’ models (including those who tie qualification attainment to minimum attendance). |

|

Services |

Ensure that there are expert, dedicated people working with the chronically absent students and their parents and whānau, using the evidence-based key practices that work, including:

|

|

Schools |

Work with services to address chronic absence, including:

|

3. We need to increase the focus on retaining students on their return

|

Who |

Action |

|

Schools |

Put in place a deliberate plan to support returning students to reintegrate, be safe, and catch up. |

|

Schools |

Actively monitor attendance of students who have previously been chronically absent and act early if their attendance declines. |

|

Ministry of Education and schools |

Increase the availability of high-quality vocational and alternative education (either in schools or through secondary-tertiary pathways), building on effective examples of flexible learning and tailored programmes from here and abroad. |

4. We need to put in place an efficient and effective model

|

Where |

Action |

|

Centralise |

Centralise key functions that can be more effectively and efficiently provided nationally, including:

|

|

Localise |

Make sure schools have the resources and the support they need to carry out the functions that most effectively happen locally, including:

Consider giving schools/clusters of schools the responsibility, accountability, and funding for the delivery of the key function of working with chronically absent students and their families, to address education barriers, while drawing on the support of the centralised function to address broader social barriers. |

|

Funding |

Increase funding for those responsible for finding students and returning them to school, reflecting that chronic absence rates have doubled since 2015. Reform how funding is allocated to ensure it matches need. |

Conclusion

ERO found that the number of students who are chronically absent from school is at crisis point, and it is affecting students’ lives. Students who have a history of chronic absence are unlikely to achieve NCEA, have higher rates of offending, are more likely to be victims of crime, and are more likely to be living in social and emergency housing. By age 20, they cost the Government almost three times as much as students who go to school.

The system that is set up to get these students back to school is not effective. It needs substantial reform, and it will take parents and whānau, schools, and Government agencies all working together to fix it and get chronically absent students back to school.

About this report

In Term 2 this year, over 80,000 students missed more than three weeks of school. These students who are chronically absent are often struggling, at high risk of poor education outcomes, and poor lifetime outcomes.

This report looks at how good the system and supports are for chronic absence in Aotearoa New Zealand. It explores the reasons for chronic student absence, and the outcomes for students who miss significant portions of their schooling.

The Education Review Office (ERO) worked with the Social Investment Agency (SIA) and the Ministry of Education to produce this report. It looks at how well the education system identifies the students who are chronically absent or not enrolled, and how well it works with them and their parents and whānau to get them attending school regularly.

- The Education Review Office is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early learning services, kura, and schools. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports young people’s outcomes.

- The Social Investment Agency is responsible for leading the implementation of social investment and providing cross-sector insights to decision makers.

- The Ministry of Education is responsible for managing policy and performance for the education system, and delivering services and support locally, regionally, and nationally. It does this to ‘shape an education system that delivers excellent and equitable outcomes.’

We also worked closely with an Expert Advisory Group with a range of expertise, including academics, school leaders, Attendance Service staff, and staff from agencies that work to improve student attendance.

ERO’s related evaluation reports

This evaluation builds on our previous work on regular attendance, and a programme of work looking at disengaged students:

- An Alternative Education? Support for our most disengaged young people

- Learning in residential care: They knew I wanted to learn

A key finding from this work is that students who are chronically absent from school are either disengaged or at risk of disengaging from their learning.

What ERO looked at

This evaluation looks at the effectiveness and value for money of interventions aimed at getting chronically absent students back to school and keeping them there. We answer five key questions.

- Who are the students who are chronically absent from school?

- Why are they absent?

- What are the outcomes for students who are chronically absent from school and what are the costs of those outcomes?

- How effective are the supports and interventions for students who are chronically absent at getting students back into school and keeping them in school? Are different models more or less effective?

- What needs to change so that the supports and interventions for students who are chronically absent from school achieve better results and are cost-effective?

This report looks at students who are chronically absent, which means they miss three weeks or more a term (attending school for 70 percent or less of the time).

How we evaluated education provision

We have taken a robust, mixed-methods approach, using an evidence-based rubric to assess how well the system, schools and Attendance Services carry out the practices that are known to successfully return chronically absent students to school. To understand how effective the supports and interventions are at increasing attendance for students who are chronically absent, we used multiple sources of information, set out below.

|

Surveys of: |

Two-thirds of Attendance Services |

|

773 students with a history of chronic absence, 256 of which were chronically absent in the last week |

|

|

1,131 parents and whānau of students with attendance issues, 311 of which were parents of students who were chronically absent in the last week |

|

|

Nearly 300 school leaders |

|

|

Interviews and focus groups with: |

Attendance Service staff |

|

Students |

|

|

Parents and whānau |

|

|

School leaders |

|

|

Site-visits at: |

One-quarter of Attendance Services |

|

28 English medium schools |

|

Data from: |

Integrated Data Infrastructure analysis |

|

Ministry of Education data and statistics on attendance, and administrative data from Attendance Services |

|

|

Findings from the Ministry of Education’s internal review of the management and support of the Attendance Service |

|

|

International evidence on effective practice in addressing chronic absence, including models from other jurisdictions |

Analysing data in the Integrated Data Infrastructure

The Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) is a large research database of people in Aotearoa New Zealand, that brings together administrative data from Government agencies, StatsNZ surveys, and non-government organisations (NGOs). Education data including school attendance, referrals to the Attendance Service, and qualifications, are all captured in the IDI.

We worked with SIA who used the IDI to provide analyses on:

- the characteristics and prior experiences of students who are referred to the Attendance Service, and the predictors and drivers of being referred

- the characteristics and prior experiences of students who are chronically absent, and the predictors and drivers of being chronically absent

- the longer-term outcomes of students who are referred to the Attendance Service

- the longer-term outcomes of students who are chronically absent

- the effectiveness of the Attendance Service, in terms of longer-term outcomes

- costs to the Government of students with chronic absence, compared to other groups.

Further details of how we evaluated provision, including the work done in the IDI, can be found in our companion technical report [LINK].

Who is missing?

Data from the IDI and administrative data is comprehensive. However, the voices of young people who are not enrolled in school or do not attend school regularly are difficult to access. While we have captured some of their voices, the majority of students in our sample either attend school some of the time or have been successfully returned to education.

Students and their parents and whānau from primary schools, kura Kaupapa Māori, and rural schools are under-represented in our sample. School leaders from schools that serve low socio-economic communities and primary schools are also under-represented in our surveys.

Report structure

This report has nine parts.

- Part 1 sets out the system for attendance in Aotearoa New Zealand.

- Part 2 describes how well attendance is going in Aotearoa New Zealand.

- Part 3 explores what is driving chronic absence from school.

- Part 4 shares the outcomes for students who are chronically absent.

- Part 5 sets out what the evidence says is key to reducing chronic absence.

- Part 6 describes how effective the Aotearoa New Zealand model is against that evidence.

- Part 7 describes how effective Attendance Services are.

- Part 8 describes how effective schools are at addressing chronic absence.

- Part 9 sets out our key findings, and the areas for action to drive improvement in student attendance.

In Term 2 this year, over 80,000 students missed more than three weeks of school. These students who are chronically absent are often struggling, at high risk of poor education outcomes, and poor lifetime outcomes.

This report looks at how good the system and supports are for chronic absence in Aotearoa New Zealand. It explores the reasons for chronic student absence, and the outcomes for students who miss significant portions of their schooling.

The Education Review Office (ERO) worked with the Social Investment Agency (SIA) and the Ministry of Education to produce this report. It looks at how well the education system identifies the students who are chronically absent or not enrolled, and how well it works with them and their parents and whānau to get them attending school regularly.

- The Education Review Office is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early learning services, kura, and schools. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports young people’s outcomes.

- The Social Investment Agency is responsible for leading the implementation of social investment and providing cross-sector insights to decision makers.

- The Ministry of Education is responsible for managing policy and performance for the education system, and delivering services and support locally, regionally, and nationally. It does this to ‘shape an education system that delivers excellent and equitable outcomes.’

We also worked closely with an Expert Advisory Group with a range of expertise, including academics, school leaders, Attendance Service staff, and staff from agencies that work to improve student attendance.

ERO’s related evaluation reports

This evaluation builds on our previous work on regular attendance, and a programme of work looking at disengaged students:

- An Alternative Education? Support for our most disengaged young people

- Learning in residential care: They knew I wanted to learn

A key finding from this work is that students who are chronically absent from school are either disengaged or at risk of disengaging from their learning.

What ERO looked at

This evaluation looks at the effectiveness and value for money of interventions aimed at getting chronically absent students back to school and keeping them there. We answer five key questions.

- Who are the students who are chronically absent from school?

- Why are they absent?

- What are the outcomes for students who are chronically absent from school and what are the costs of those outcomes?

- How effective are the supports and interventions for students who are chronically absent at getting students back into school and keeping them in school? Are different models more or less effective?

- What needs to change so that the supports and interventions for students who are chronically absent from school achieve better results and are cost-effective?

This report looks at students who are chronically absent, which means they miss three weeks or more a term (attending school for 70 percent or less of the time).

How we evaluated education provision

We have taken a robust, mixed-methods approach, using an evidence-based rubric to assess how well the system, schools and Attendance Services carry out the practices that are known to successfully return chronically absent students to school. To understand how effective the supports and interventions are at increasing attendance for students who are chronically absent, we used multiple sources of information, set out below.

|

Surveys of: |

Two-thirds of Attendance Services |

|

773 students with a history of chronic absence, 256 of which were chronically absent in the last week |

|

|

1,131 parents and whānau of students with attendance issues, 311 of which were parents of students who were chronically absent in the last week |

|

|

Nearly 300 school leaders |

|

|

Interviews and focus groups with: |

Attendance Service staff |

|

Students |

|

|

Parents and whānau |

|

|

School leaders |

|

|

Site-visits at: |

One-quarter of Attendance Services |

|

28 English medium schools |

|

Data from: |

Integrated Data Infrastructure analysis |

|

Ministry of Education data and statistics on attendance, and administrative data from Attendance Services |

|

|

Findings from the Ministry of Education’s internal review of the management and support of the Attendance Service |

|

|

International evidence on effective practice in addressing chronic absence, including models from other jurisdictions |

Analysing data in the Integrated Data Infrastructure

The Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) is a large research database of people in Aotearoa New Zealand, that brings together administrative data from Government agencies, StatsNZ surveys, and non-government organisations (NGOs). Education data including school attendance, referrals to the Attendance Service, and qualifications, are all captured in the IDI.

We worked with SIA who used the IDI to provide analyses on:

- the characteristics and prior experiences of students who are referred to the Attendance Service, and the predictors and drivers of being referred

- the characteristics and prior experiences of students who are chronically absent, and the predictors and drivers of being chronically absent

- the longer-term outcomes of students who are referred to the Attendance Service

- the longer-term outcomes of students who are chronically absent

- the effectiveness of the Attendance Service, in terms of longer-term outcomes

- costs to the Government of students with chronic absence, compared to other groups.

Further details of how we evaluated provision, including the work done in the IDI, can be found in our companion technical report [LINK].

Who is missing?

Data from the IDI and administrative data is comprehensive. However, the voices of young people who are not enrolled in school or do not attend school regularly are difficult to access. While we have captured some of their voices, the majority of students in our sample either attend school some of the time or have been successfully returned to education.

Students and their parents and whānau from primary schools, kura Kaupapa Māori, and rural schools are under-represented in our sample. School leaders from schools that serve low socio-economic communities and primary schools are also under-represented in our surveys.

Report structure

This report has nine parts.

- Part 1 sets out the system for attendance in Aotearoa New Zealand.

- Part 2 describes how well attendance is going in Aotearoa New Zealand.

- Part 3 explores what is driving chronic absence from school.

- Part 4 shares the outcomes for students who are chronically absent.

- Part 5 sets out what the evidence says is key to reducing chronic absence.

- Part 6 describes how effective the Aotearoa New Zealand model is against that evidence.

- Part 7 describes how effective Attendance Services are.

- Part 8 describes how effective schools are at addressing chronic absence.

- Part 9 sets out our key findings, and the areas for action to drive improvement in student attendance.

Part 1: What is the system for attendance in Aotearoa New Zealand?

Attendance is crucial for children to learn. Students are expected to be in school learning every day. All children aged between six and 16 years old are required to be enrolled in a school in Aotearoa New Zealand. Once they are enrolled, children must attend school if it is open. If a student misses more than 30 percent of school a term, or three weeks, they are chronically absent. Schools must take all reasonable steps to make students attend school, while the Attendance Service works with the students who are chronically absent, or not enrolled. Police and statutory attendance officers can return students to school or home.

Schools, Attendance Services, parents and whānau, and students all have responsibilities for ensuring attendance.

This section sets out:

- the expectations for going to school

- what counts as ‘going to school’

- who is responsible for what

- how this works in practice.

1. What are the expectations for going to school?

All students in Aotearoa New Zealand are expected to be enrolled in school and they must attend school if it is open.

Attendance is critical for learning and thriving at school.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the law requires all children aged six to 16 to be enrolled in a registered school, unless they have an exemption by the Ministry of Education. The Ministry of Education may issue an exemption for reasons such as:

- the student being homeschooled

- the student being in Oranga Tamariki residential care

- the student living too far away from a school.

All students under the age of 16 who are enrolled in a school must attend the school if it is open.

2. What counts as ‘going to school’?

Schools must record student attendance every day, and student attendance is reported in ‘half days’. Primary schools typically record attendance first thing in the morning, and again after lunch. Secondary schools typically record attendance for each class or lesson.

Students are present at school when they are in class (see Appendix 2 for a list of cases where students are counted as ‘present’).

There are four different categories of attendance, depending on how many half-days a student attends in a school term. This report focuses on chronically absent students, who are those that attend for 70 percent or less of a term (missing 15 days or more of a 10-week term).

All types of absence contribute to chronic absence, but some reasons for missing school are considered reasonable or ‘justified’. There are guidelines for schools, but what counts as a justified absence depends on each school’s policy. Justified absences are for things like illness or bereavement. School policies also determine what counts as an ‘unjustified absence’. Unjustified absences are when the school does not receive an explanation for an absence, or they decide an explanation is not a sufficient reason for not attending school. See Appendix 2 for more detail on the different types of absences.

3. Who is responsible for what?

a) Schools

Schools must take all reasonable steps to make sure students attend school when the school is open.

Schools are required to keep accurate records of who is enrolled and their attendance. They are expected to provide attendance data to the Ministry of Education.

If a student is expected at school and does not turn up, schools must notify the student’s parent or caregiver, and take action. What action schools take, and when, depends on each school’s attendance policies and procedures.

School boards must take ‘all reasonable steps’ to make sure students attend school when the school is open. These reasonable steps are expected to be set out in each school’s attendance management policy. Attendance management policies should also set out the school’s rules for attendance, how the school records attendance, and how the school will respond to student absences. School boards may also appoint a statutory attendance officer (see section below on statutory attendance officers).

b) Attendance Services

Attendance Services work with students who are chronically absent from school or not enrolled to return them to school.

Attendance Services are contracted by the Ministry of Education to help schools manage attendance by working with students and their parents and whānau. They work to address the root causes of absence or non-enrolment. Attendance Services are expected to:

- work with schools, students, and their parents and whānau, to identify why students are not going to school, and work out how to get them back to regular attendance at school

- respond to all referrals, which are made through the Attendance Services Application system (ASA)

- tailor their approach based on what works in their community

- work with other agencies, like Oranga Tamariki, Whānau Ora, the Ministry of Social Development or NZ Police, iwi, and services in their community, to help make sure students are able to return to school and sustain their attendance

- get students back to school.

Each year, the Ministry of Education spends $22.8 million on contracts with 78 different Attendance Service providers, covering 84 service areas, and employing around 210 full-time equivalent staff. These providers are a mix of schools, iwi providers, and NGOs.

Attendance Services are accountable through their contracts to deliver a set of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs, see the companion technical report for more detail). The Attendance Service managers report to, and meet regularly with, the Ministry of Education.

Attendance Officers work with schools and parents and whānau to address moderate or irregular absence.

Attendance Officers are employed by Attendance Services. They work with schools and communities to address moderate and irregular absence patterns for students in Years 1 to 12. They are expected to focus on helping schools to analyse their attendance data, identify patterns of attendance, and develop and implement processes to improve attendance for students who are not yet chronically absent, but have unsatisfactory attendance.

In 2023, the Government allocated an additional $9 million per year to fund 82 full-time equivalent Attendance Officer roles. 76 FTE roles are allocated across Attendance Service providers and may be called different things in each community.

There are also Attendance Officers with statutory powers who are appointed by school boards to help them manage student attendance. School boards can appoint these Attendance Officers from Attendance Services staff or someone outside of it, and these roles are funded through school operations grants.

c) Parents and whānau

Parents and guardians (along with schools) are responsible for sending their children to school and making sure they are attending regularly. If they fail to do so and their child is prosecuted for chronic absence they will be charged. Parents and guardians may be charged and fined up to $30 for every day their child is absent or not enrolled in a school. For a first offence, they can be fined a maximum of $300; subsequent offenses are limited to $3,000.

d) Other services

Police and statutory attendance officers can return students to school or home.

There are two roles with statutory powers to enforce school attendance: the Police and statutory attendance officers. Attendance officers with statutory powers (statutory attendance officers) are people appointed by school boards to help them manage student attendance. They are, confusingly, not the same as Attendance Officers in Attendance Services, who do not have statutory powers unless the school board also appoints them as a statutory attendance officer.

Statutory attendance officers are allowed to detain students who appear to be aged between five and 16, and take them home or to their school. They have to show some sort of proof they have been appointed by a school board as a statutory attendance officer.

4. How does this work in practice?

Firstly, a teacher will notice, or schools will use attendance data to identify, when students have missed a lot of school. The monitoring of the attendance data may be carried out at the school, or by an Attendance Officer that works with school. Sometimes other people contact the school reporting a concern that a child is not at school.

Once schools have identified that a student has a high rate of absence, they reach out to the student, and their parents and whānau, to understand why. The school will then work directly with the student’s parents or whānau to address any barriers and get them attending more frequently.

For students that do not return, one of two things can happen:

- the school refers the student to an Attendance Service

- the school provides more intensive support, often through school based social services like Social Workers in Schools, or school-based Attendance Officers.

For students referred to the Attendance Service, the service will contact their parents and whānau, and work with them and the student to address barriers to attendance and get them back to school.

Once the student is returned to school, the Attendance Service hands the case back to the school and closes the case.

If the student does not return after intervention by schools and Attendance Services, the parents or guardians may be fined or prosecuted.

In some cases, students stop attending completely. If a student misses 20 days of school in a row without communicating properly with the school, the school may remove them from their roll.

Conclusion

Attendance matters, and in Aotearoa New Zealand, all children aged six to 16 are legally required to be enrolled in a registered school, unless they have an exemption by the Ministry of Education.

Schools must take all ‘reasonable steps’ to make sure students attend school when the school is open, and Attendance Services work with students who are chronically absent from school or not enrolled, to return them to school.

In the next chapter, we examine the extent of the chronic absence problem in Aotearoa New Zealand, and how effective our system is for getting children back to school.

Attendance is crucial for children to learn. Students are expected to be in school learning every day. All children aged between six and 16 years old are required to be enrolled in a school in Aotearoa New Zealand. Once they are enrolled, children must attend school if it is open. If a student misses more than 30 percent of school a term, or three weeks, they are chronically absent. Schools must take all reasonable steps to make students attend school, while the Attendance Service works with the students who are chronically absent, or not enrolled. Police and statutory attendance officers can return students to school or home.

Schools, Attendance Services, parents and whānau, and students all have responsibilities for ensuring attendance.

This section sets out:

- the expectations for going to school

- what counts as ‘going to school’

- who is responsible for what

- how this works in practice.

1. What are the expectations for going to school?

All students in Aotearoa New Zealand are expected to be enrolled in school and they must attend school if it is open.

Attendance is critical for learning and thriving at school.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the law requires all children aged six to 16 to be enrolled in a registered school, unless they have an exemption by the Ministry of Education. The Ministry of Education may issue an exemption for reasons such as:

- the student being homeschooled

- the student being in Oranga Tamariki residential care

- the student living too far away from a school.

All students under the age of 16 who are enrolled in a school must attend the school if it is open.

2. What counts as ‘going to school’?

Schools must record student attendance every day, and student attendance is reported in ‘half days’. Primary schools typically record attendance first thing in the morning, and again after lunch. Secondary schools typically record attendance for each class or lesson.

Students are present at school when they are in class (see Appendix 2 for a list of cases where students are counted as ‘present’).

There are four different categories of attendance, depending on how many half-days a student attends in a school term. This report focuses on chronically absent students, who are those that attend for 70 percent or less of a term (missing 15 days or more of a 10-week term).

All types of absence contribute to chronic absence, but some reasons for missing school are considered reasonable or ‘justified’. There are guidelines for schools, but what counts as a justified absence depends on each school’s policy. Justified absences are for things like illness or bereavement. School policies also determine what counts as an ‘unjustified absence’. Unjustified absences are when the school does not receive an explanation for an absence, or they decide an explanation is not a sufficient reason for not attending school. See Appendix 2 for more detail on the different types of absences.

3. Who is responsible for what?

a) Schools

Schools must take all reasonable steps to make sure students attend school when the school is open.

Schools are required to keep accurate records of who is enrolled and their attendance. They are expected to provide attendance data to the Ministry of Education.

If a student is expected at school and does not turn up, schools must notify the student’s parent or caregiver, and take action. What action schools take, and when, depends on each school’s attendance policies and procedures.

School boards must take ‘all reasonable steps’ to make sure students attend school when the school is open. These reasonable steps are expected to be set out in each school’s attendance management policy. Attendance management policies should also set out the school’s rules for attendance, how the school records attendance, and how the school will respond to student absences. School boards may also appoint a statutory attendance officer (see section below on statutory attendance officers).

b) Attendance Services

Attendance Services work with students who are chronically absent from school or not enrolled to return them to school.

Attendance Services are contracted by the Ministry of Education to help schools manage attendance by working with students and their parents and whānau. They work to address the root causes of absence or non-enrolment. Attendance Services are expected to:

- work with schools, students, and their parents and whānau, to identify why students are not going to school, and work out how to get them back to regular attendance at school

- respond to all referrals, which are made through the Attendance Services Application system (ASA)

- tailor their approach based on what works in their community

- work with other agencies, like Oranga Tamariki, Whānau Ora, the Ministry of Social Development or NZ Police, iwi, and services in their community, to help make sure students are able to return to school and sustain their attendance

- get students back to school.

Each year, the Ministry of Education spends $22.8 million on contracts with 78 different Attendance Service providers, covering 84 service areas, and employing around 210 full-time equivalent staff. These providers are a mix of schools, iwi providers, and NGOs.

Attendance Services are accountable through their contracts to deliver a set of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs, see the companion technical report for more detail). The Attendance Service managers report to, and meet regularly with, the Ministry of Education.

Attendance Officers work with schools and parents and whānau to address moderate or irregular absence.

Attendance Officers are employed by Attendance Services. They work with schools and communities to address moderate and irregular absence patterns for students in Years 1 to 12. They are expected to focus on helping schools to analyse their attendance data, identify patterns of attendance, and develop and implement processes to improve attendance for students who are not yet chronically absent, but have unsatisfactory attendance.

In 2023, the Government allocated an additional $9 million per year to fund 82 full-time equivalent Attendance Officer roles. 76 FTE roles are allocated across Attendance Service providers and may be called different things in each community.

There are also Attendance Officers with statutory powers who are appointed by school boards to help them manage student attendance. School boards can appoint these Attendance Officers from Attendance Services staff or someone outside of it, and these roles are funded through school operations grants.

c) Parents and whānau

Parents and guardians (along with schools) are responsible for sending their children to school and making sure they are attending regularly. If they fail to do so and their child is prosecuted for chronic absence they will be charged. Parents and guardians may be charged and fined up to $30 for every day their child is absent or not enrolled in a school. For a first offence, they can be fined a maximum of $300; subsequent offenses are limited to $3,000.

d) Other services

Police and statutory attendance officers can return students to school or home.

There are two roles with statutory powers to enforce school attendance: the Police and statutory attendance officers. Attendance officers with statutory powers (statutory attendance officers) are people appointed by school boards to help them manage student attendance. They are, confusingly, not the same as Attendance Officers in Attendance Services, who do not have statutory powers unless the school board also appoints them as a statutory attendance officer.

Statutory attendance officers are allowed to detain students who appear to be aged between five and 16, and take them home or to their school. They have to show some sort of proof they have been appointed by a school board as a statutory attendance officer.

4. How does this work in practice?

Firstly, a teacher will notice, or schools will use attendance data to identify, when students have missed a lot of school. The monitoring of the attendance data may be carried out at the school, or by an Attendance Officer that works with school. Sometimes other people contact the school reporting a concern that a child is not at school.

Once schools have identified that a student has a high rate of absence, they reach out to the student, and their parents and whānau, to understand why. The school will then work directly with the student’s parents or whānau to address any barriers and get them attending more frequently.

For students that do not return, one of two things can happen:

- the school refers the student to an Attendance Service

- the school provides more intensive support, often through school based social services like Social Workers in Schools, or school-based Attendance Officers.

For students referred to the Attendance Service, the service will contact their parents and whānau, and work with them and the student to address barriers to attendance and get them back to school.

Once the student is returned to school, the Attendance Service hands the case back to the school and closes the case.

If the student does not return after intervention by schools and Attendance Services, the parents or guardians may be fined or prosecuted.

In some cases, students stop attending completely. If a student misses 20 days of school in a row without communicating properly with the school, the school may remove them from their roll.

Conclusion

Attendance matters, and in Aotearoa New Zealand, all children aged six to 16 are legally required to be enrolled in a registered school, unless they have an exemption by the Ministry of Education.

Schools must take all ‘reasonable steps’ to make sure students attend school when the school is open, and Attendance Services work with students who are chronically absent from school or not enrolled, to return them to school.

In the next chapter, we examine the extent of the chronic absence problem in Aotearoa New Zealand, and how effective our system is for getting children back to school.

Part 2: How big is the problem of chronic absence in Aotearoa New Zealand?

Aotearoa New Zealand is experiencing a crisis of chronic absence. Chronic absence has doubled since 2015 and is now at 10 percent. This means one in 10 students are missing three weeks or more a term.

In this chapter we set out how much students are attending school, and how chronic absence varies for different students and schools.

What we did to understand how big the problem of chronic absence is

We used Ministry of Education administrative data to understand how big the problem of chronic absence is, and who the students are who miss more than 30 percent of school.

This section sets out what we found out about:

- how many students are not attending school

- how chronic absence is different for different students

- how attendance varies by school.

What we found: an overview

Chronic absence has doubled since 2015.

One in 10 students (10 percent) were chronically absent in Term 2, 2024. Over 80,000 students were attending school less than 70 percent of the term.

Senior secondary school students are most likely to be chronically absent.

One in seven (15 percent) senior secondary school students (Years 11-13) were chronically absent in Term 2 of 2024.

Chronic absence rates are higher in low socio-economic areas.

Students from schools in low socio-economic areas are six times as likely to be chronically absent (18 percent compared to 3 percent).

1. How many students are chronically absent from school?

Chronic absence is currently at 10 percent.

In Term 2 this year (2024), 80,569 students (10 percent of all students) were recorded as chronically absent, missing more than three weeks of a school term.

Figure 1: Percentage of students by the proportion of absence in Term 2 2024

Data Source: Ministry of Education

Chronic absence is on the rise and has doubled since 2015.

Five percent of students were chronically absent in Term 2 in 2015. Chronic absence started to increase in 2016, and in Term 2 2024, 10 percent of students were chronically absent.

Figure 2: Percentage of chronic absence in 2015 and 2024 Term 2

Data Source: Ministry of Education

2. How is chronic absence different for different students?

Most chronically absent students are away for three weeks in a term, but some miss a whole term.

In Term 2 of 2024, just under half of chronically absent students were away for four weeks. But there were over one percent of chronically absent students who missed the whole term (nine or more weeks).

Māori and Pacific students are more at risk of chronic absence.

In Term 2 of 2024, 18 percent of Māori students and 17 percent of Pacific students were chronically absent. This is compared to 8 percent of NZ European/Pākehā students and 6 percent of Asian students.3 Concerningly, the gap in rate of chronic absence between NZ European/Pākehā students and Māori and Pacific students has increased from pre-Covid-19 levels. The gap for Māori students has increased from 8 percentage points in 2019 to 10 percentage points in 2024. Whereas for Pacific students, chronic absence has increased from 7 percentage points in 2019 to 9 percentage points in 2024.

Figure 3: Percentage of chronically absent students by ethnicity in Term 2 2024

Data Source: Ministry of Education

There is no difference in chronic absence for gender.

Boys and girls are equally likely to be chronically absent. In Term 2 of 2024, 10 percent of both girls and boys had chronic absence.

Chronic absence rates are higher for older students.

Chronic absence is a problem in both primary and secondary school. Senior secondary school students have nearly double the rate of chronic absence as primary school students. In primary school (Years 1-8) chronic absence is 10 percent, in secondary school (Years 9-10) it is 13 percent, and in senior secondary school (Years 11-13) it is 15 percent.

Figure 4: Chronic absence rates across different year levels in Term 2 2024

Data Source: Ministry of Education

3. How is chronic absence different for different schools?

More students are becoming chronically absent at younger ages.

Chronic absence rates have doubled in secondary schools and nearly tripled in primary schools since 2015. Rates of chronic absence in secondary schools started to increase in 2015. In primary schools, rates of chronic absence started to increase in 2016. Chronic absence rates have improved since the peak of the pandemic (2022), but they remain higher than before the pandemic.

Figure 5: Rates of chronic absence in primary and secondary schools

Data Source: Ministry of Education

Attendance in primary school matters. Students who do not have a history of regular attendance are more likely to continue being chronically absent.

We found from our analysis that for students who have a history of regular attendance, their likelihood of attending school regularly increases by 221 percent. ERO’s previous work also tells us that there is a greater impact on learning the more days of school students missed. Having healthy attendance patterns in primary school helps students maintain attendance habits in secondary school.

Chronic absence rates are higher in schools in low socio-economic communities, and in the Northland | Te Tai Tokerau region.

Students from schools in low socio-economic communities4 are six times as likely to be chronically absent from school (18 percent) than students in schools in high socio-economic communities (3 percent).

Figure 6: Percentage of chronic absence by schools in socio-economic areas in 2024 Term 2

Data Source: Ministry of Education

Despite absence rates being higher in schools in low socio-economic areas, there are schools in low socio-economic communities that have low chronic absence rates and schools in high socio-economic communities that have high chronic absence rates (more about this can be found in Chapter 8).

Regionally, Northland | Te Tai Tokerau (15 percent) and Southwest Auckland | Tāmaki Herenga Waka South (15 percent) has the highest percentage of chronically absent students in Aotearoa New Zealand, followed by Hawkes Bay | Tairāwhiti, Waikato and Bay of Plenty, Waiariki (12 percent).

Figure 7: Percentage of chronic absence by regions in Term 2 2024

Data Source: Ministry of Education

Conclusion

Chronic absence in Aotearoa New Zealand has reached crisis levels, doubling since 2015. Over 80,000 students (10 percent) were chronically absent in Term 2, 2024. This has serious impacts for students. Senior secondary school students, Māori students, Pacific students, and students in schools in low socio-economic areas are at a greater risk of chronic absence.

The next section looks at the drivers for students’ absence from school, and the reasons for Aotearoa New Zealand’s high rates of chronic absence.

Aotearoa New Zealand is experiencing a crisis of chronic absence. Chronic absence has doubled since 2015 and is now at 10 percent. This means one in 10 students are missing three weeks or more a term.

In this chapter we set out how much students are attending school, and how chronic absence varies for different students and schools.

What we did to understand how big the problem of chronic absence is

We used Ministry of Education administrative data to understand how big the problem of chronic absence is, and who the students are who miss more than 30 percent of school.

This section sets out what we found out about:

- how many students are not attending school