Related insights

Explore related documents that might be interested in.

Read Online

Overview

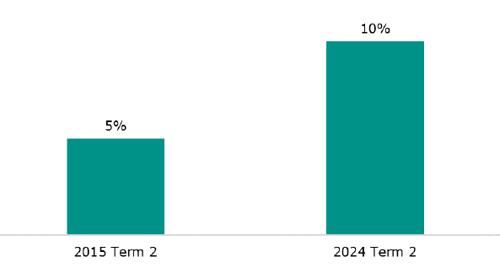

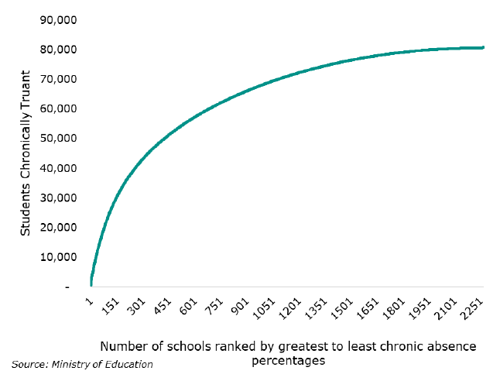

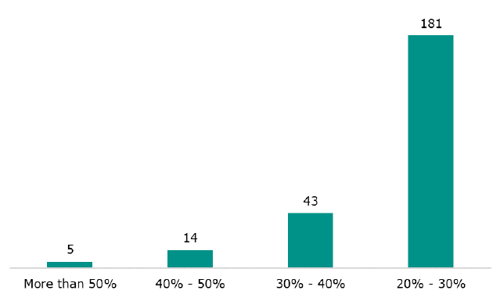

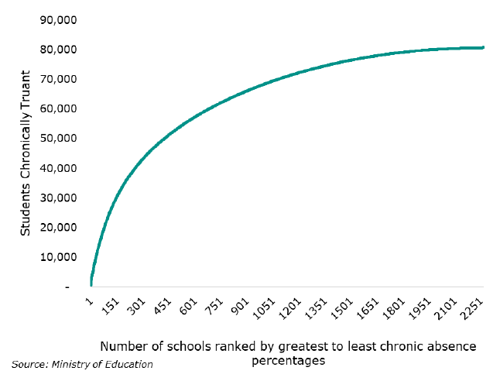

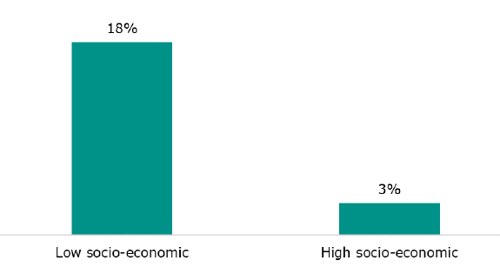

In Term 2 this year, over 80,000 students missed more than three weeks of school. These students who are chronically absent are often struggling, are at high risk of poor education outcomes, and have poor lifetime outcomes.

This technical report describes what we did to look at how good the system and supports are for chronic absence in Aotearoa New Zealand. It sets out how we explored the reasons for chronic student absence, and the outcomes for students who miss significant portions of their schooling.

Download the PDF to read the technical report.

In Term 2 this year, over 80,000 students missed more than three weeks of school. These students who are chronically absent are often struggling, are at high risk of poor education outcomes, and have poor lifetime outcomes.

This technical report describes what we did to look at how good the system and supports are for chronic absence in Aotearoa New Zealand. It sets out how we explored the reasons for chronic student absence, and the outcomes for students who miss significant portions of their schooling.

Download the PDF to read the technical report.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the extensive support from the Ministry of Education and Social Investment Agency in this work throughout the project. We also appreciate the support from an Expert Advisory Group, made up of experts and practitioners in the education and attendance fields. We acknowledge support from members of the Steering Group who provided overall guidance and support for the project.

We are grateful for the extensive support from the Ministry of Education and Social Investment Agency in this work throughout the project. We also appreciate the support from an Expert Advisory Group, made up of experts and practitioners in the education and attendance fields. We acknowledge support from members of the Steering Group who provided overall guidance and support for the project.

Chapter 1: Evaluation design

This chapter discusses how we designed the evaluation, including:

- what we looked at

- who we worked with

- how we decided what we would do

- the overall approach

- caveats

- terminology

- report structure.

1. What we looks at

Purpose of the evaluation

The Associate Minister of Education commissioned this evaluation to better understand the students who are chronically absent (70 percent or less attendance in a term) and to assess the effectiveness of Attendance Services in bringing those students back to school.

Evaluation questions

This evaluation looks at the effectiveness and value for money of interventions aimed at getting chronically absent students back to school and keeping them there. We answer five key questions.

- Who are the students who are chronically absent from school?

- Why are they absent?

- What are the outcomes for students who are chronically absent from school and what are the costs of those outcomes?

- How effective are the supports and interventions for students who are chronically absent at getting students back into school and keeping them in school? Are different models more or less effective?

- What needs to change so that the supports and interventions for students who are chronically absent from school achieve better results and are cost-effective?

This report looks at students who are chronically absent, which means they miss three weeks or more a term (attending school for 70 percent of the time or less).

2. Who we worked with

The Education Review Office (ERO) worked with the Social Investment Agency (SIA) and the Ministry of Education (the Ministry) to produce this report. It looks at how well the education system identifies the students who are chronically absent or not enrolled, and how well it works with them and their parents and whānau to get them attending school regularly.

- The Education Review Office is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early learning services, kura, and schools. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports young people’s outcomes.

- The Social Investment Agency is responsible for leading the implementation of social investment and providing cross-sector insights to decision makers.

- The Ministry of Education is responsible for managing policy and performance for the education system, and delivering services and support locally, regionally, and nationally. It does this to ‘shape an education system that delivers excellent and equitable outcomes.’

We also worked closely with an Expert Advisory Group with a range of proficiencies, including academics, school leaders, Attendance Service staff, and staff from agencies that work to improve student attendance.

3. How we decide what we would do

We engaged an Expert Advisory Group to provide specialist expertise and evidence-based perspectives to inform, critique, and support this evaluation. We also drew on the experience of methodology experts at SIA and within ERO to determine which areas to focus our evaluation on.

This evaluation used a mixed-methods approach to ensure that our data is robust and that we are hearing the experiences of students, school leaders, Attendance Service staff, and parents and whānau.

4. The overall approach

Mixed-methods

ERO used a mixed-methods approach, drawing on a wide range of administrative data, site visits, surveys, and interviews. This report draws on the voices of students, school leaders, Attendance Services, parents and whānau, and experts to understand chronic absence and its implications on the students in the long term.

The Ministry provided data on attendance rates in schools, and attendance rates by different demographics and subgroups.

The SIA provided analysis on the outcomes of students who were chronically absent, and those who were referred to Attendance Services. The SIA also provided data on the monetary cost associated with chronically absent students.

Data that informed the evaluation

The table below describes the data we used to inform each question.

|

Key evaluation question |

Data we used to answer this question |

|

Who are the students who are chronically absent from school? |

Ministry administrative data |

|

IDI |

|

|

Why are they absent? |

Surveys of students, parents and whānau, Attendance Service staff, and schools |

|

Interviews with students, parents and whānau, Attendance Service staff, and schools |

|

|

What are the outcomes for students who are chronically absent from school and what are the costs of those outcomes? |

IDI |

|

How effective are the supports and interventions for students who are chronically absent at getting students back into school and keeping them there? Are different models more or less effective?

|

IDI |

|

Surveys of students, parents and whānau, Attendance Service staff, and schools |

|

|

Interviews with students, parents and whānau, Attendance Service staff, and schools |

|

|

What needs to change so that the supports and interventions for students who are chronically absent from school achieve better results and are cost-effective? |

Surveys of students, parents and whānau, Attendance Service staff, and schools |

|

Interviews with students, parents and whānau, Attendance Service staff, and schools |

Ethics

All participants were informed of the purpose of the evaluation before they agreed to participate in an interview. Participants were informed that:

- participation was voluntary and could be withdrawn at any time

- their words may be included in reporting, but no identifying details would be shared

- permission to use their information could be withdrawn at any time

- interviews were not an evaluation of their school, and their school or provider would not be identified in the resulting national report

- their information was confidential and would be kept securely subject to the provisions of the Official Information Act 1982, Privacy Act 1993, and the Public Records Act 2005 on the release and retention of information.

Interviewees consented to take part in an interview via email, or by submitting a written consent form to ERO. Their verbal consent was also sought to record their online interviews. Participants were given opportunities to query the evaluation team if they needed further information about the consent process.

Data collected from interviews, surveys, and administrative data will be stored digitally for a period of six months after the full completion of the evaluation. During this time, all data will be password-protected and have limited accessibility.

Quality assurance

The data in this report was subjected to a rigorous internal review process for both quantitative and qualitative data, which was carried out at multiple stages across the evaluation process. External data provided by the Ministry and SIA was reviewed by them.

5. The caveats for this report

Administrative attendance data

Administrative attendance records are comprehensive. They contain information on the attendance of students who are enrolled at schools in Aotearoa New Zealand.

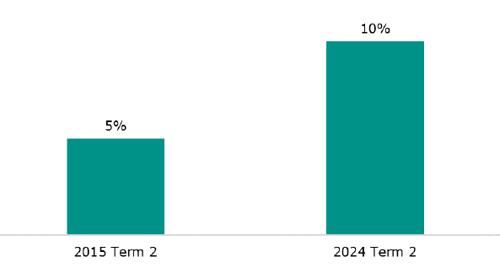

The latest data on attendance used in this report is from Term 2, 2024.

Surveys

The surveys were focused on students who have been chronically absent and their parents and whānau. Responses are representative of chronically absent Māori and Pacific students, but are over representative of chronically absent Pākehā students (respondents were able to select multiple ethnicities). To ensure robustness, the survey results are complemented with administrative data, including Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) analysis, to draw conclusions.

Integrated Data Infrastructure

Data from the IDI is comprehensive. It contains information on attendance of students who are enrolled in Aotearoa New Zealand schools from 2011 onwards. However, the voices of young people who are not enrolled in school or do not attend school regularly are difficult to access. While we have captured some of their voices, the majority of students in our sample either attend school some of the time or have been successfully returned to education.

IDI data disclaimers

These results are not official statistics. They have been created for research purposes from the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) which is carefully managed by Stats NZ. For more information about the IDI please visit: https://www.stats.govt.nz/integrated-data/.

The results are based in part on tax data supplied by Inland Revenue to Stats NZ under the Tax Administration Act 1994 for statistical purposes. Any discussion of data limitations or weaknesses is in the context of using IDI for statistical purposes, and is not related to the data’s ability to support Inland Revenue’s core operational requirements.

6. Terminology

What is chronic absence?

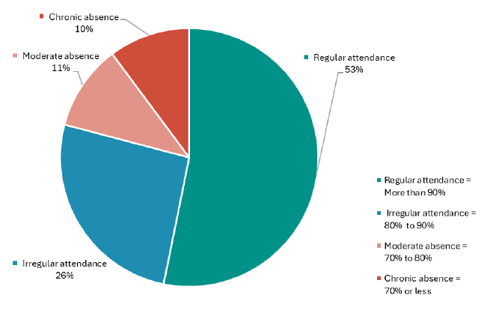

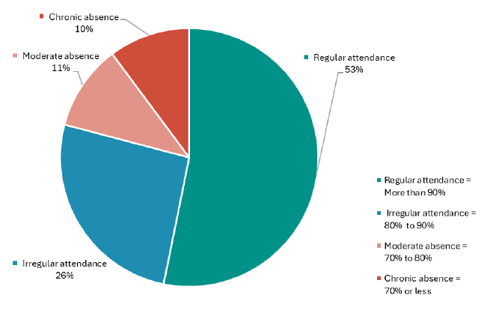

There are four different categories of attendance, depending on how many half-days a student attends in a school term. These are set out below.

- Regular attendance: attend 90 percent or more of a term (missing up to five days of a 10-week term).

- Irregular absence: attend 80 to 90 percent of a term (missing five to 10 days of a 10-week term).

- Moderate absence: attend 70 to 80 percent of a term (missing 10 to 15 days of a 10-week term).

- Chronic absence: attend less than 70 percent of a term (missing 15 days or more of a 10-week term). This report focuses on this group of students.

What counts as ‘going to school’?

Students are present at school when they are in class. They are also considered present when they are:

- late to class (but within school policy for lateness)

- on the school site, doing things like:

- unsupervised study

- sitting an exam

- having an appointment at school (e.g., with a dean, sports coach, or nurse)

- waiting in the sickbay

- in-school isolation (e.g., removed to a different class or in the administration corridor) - away from school, but doing a school-based activity, like

- a sports trip or cultural presentation

- camp - learning somewhere else, as agreed with the school, like:

- Alternative Education, Secondary Tertiary Programme (including Trades Academies), or Activity Centre

- Teen Parent Unit, Health Camp, or Regional Health School

- a course or work experience - at a medical or dental appointment, or attending to Justice Court proceedings.

Different types of absences

Table 1: Justified and unjustified absences

|

Justified absence |

Unjustified absence |

|

Students are marked as having a ‘justified absence’ if they are away from school for:

- representing at a local or national level in a sporting or cultural event - bereavement - unplanned absences like extreme weather

Students are marked as being ‘overseas (justified)’ if they are accompanying or visiting a family member on an overseas posting, for up to 15 weeks. If it is longer than 15 weeks, their absence becomes unjustified. |

Students are marked as having an ‘unjustified absence’ if they:

|

Abbreviations

- IDI: The Integrated Data Infrastructure is a large research database maintained by Stats NZ. It holds de-identified microdata about people and households.

- ERO: Education Review Office

- The Ministry: Ministry of Education

- SIA: Social Investment Agency

- UE: Un-enrolled students

- UA: Unjustified absence

- N: Number of responses

7. Report structure

This report has 10 chapters.

- Chapter 1: Evaluation design

- Chapter 2: Analytical tools – Data and Methodology

- Chapter 3: How well attendance is going in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Chapter 4: What is driving chronic absence from school

- Chapter 5: The outcomes for students who are chronically absent

- Chapter 6: How effective the Aotearoa New Zealand model is against that evidence

- Chapter 7: How effective Attendance Services are

- Chapter 8: How effective schools are at addressing chronic absence

- Chapter 9: Our key findings and the areas for action to drive improvement in student attendance

- Chapter 10: Limitations of this research

Conclusion

ERO was commissioned to look at students who are chronically absent and the effectiveness of Attendance Services in bringing those students back to school. We used a mixed-methods approach, drawing on a wide range of administrative data, site visits, surveys, and interviews.

The next chapter describes the tools and analysis methods we used.

This chapter discusses how we designed the evaluation, including:

- what we looked at

- who we worked with

- how we decided what we would do

- the overall approach

- caveats

- terminology

- report structure.

1. What we looks at

Purpose of the evaluation

The Associate Minister of Education commissioned this evaluation to better understand the students who are chronically absent (70 percent or less attendance in a term) and to assess the effectiveness of Attendance Services in bringing those students back to school.

Evaluation questions

This evaluation looks at the effectiveness and value for money of interventions aimed at getting chronically absent students back to school and keeping them there. We answer five key questions.

- Who are the students who are chronically absent from school?

- Why are they absent?

- What are the outcomes for students who are chronically absent from school and what are the costs of those outcomes?

- How effective are the supports and interventions for students who are chronically absent at getting students back into school and keeping them in school? Are different models more or less effective?

- What needs to change so that the supports and interventions for students who are chronically absent from school achieve better results and are cost-effective?

This report looks at students who are chronically absent, which means they miss three weeks or more a term (attending school for 70 percent of the time or less).

2. Who we worked with

The Education Review Office (ERO) worked with the Social Investment Agency (SIA) and the Ministry of Education (the Ministry) to produce this report. It looks at how well the education system identifies the students who are chronically absent or not enrolled, and how well it works with them and their parents and whānau to get them attending school regularly.

- The Education Review Office is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early learning services, kura, and schools. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports young people’s outcomes.

- The Social Investment Agency is responsible for leading the implementation of social investment and providing cross-sector insights to decision makers.

- The Ministry of Education is responsible for managing policy and performance for the education system, and delivering services and support locally, regionally, and nationally. It does this to ‘shape an education system that delivers excellent and equitable outcomes.’

We also worked closely with an Expert Advisory Group with a range of proficiencies, including academics, school leaders, Attendance Service staff, and staff from agencies that work to improve student attendance.

3. How we decide what we would do

We engaged an Expert Advisory Group to provide specialist expertise and evidence-based perspectives to inform, critique, and support this evaluation. We also drew on the experience of methodology experts at SIA and within ERO to determine which areas to focus our evaluation on.

This evaluation used a mixed-methods approach to ensure that our data is robust and that we are hearing the experiences of students, school leaders, Attendance Service staff, and parents and whānau.

4. The overall approach

Mixed-methods

ERO used a mixed-methods approach, drawing on a wide range of administrative data, site visits, surveys, and interviews. This report draws on the voices of students, school leaders, Attendance Services, parents and whānau, and experts to understand chronic absence and its implications on the students in the long term.

The Ministry provided data on attendance rates in schools, and attendance rates by different demographics and subgroups.

The SIA provided analysis on the outcomes of students who were chronically absent, and those who were referred to Attendance Services. The SIA also provided data on the monetary cost associated with chronically absent students.

Data that informed the evaluation

The table below describes the data we used to inform each question.

|

Key evaluation question |

Data we used to answer this question |

|

Who are the students who are chronically absent from school? |

Ministry administrative data |

|

IDI |

|

|

Why are they absent? |

Surveys of students, parents and whānau, Attendance Service staff, and schools |

|

Interviews with students, parents and whānau, Attendance Service staff, and schools |

|

|

What are the outcomes for students who are chronically absent from school and what are the costs of those outcomes? |

IDI |

|

How effective are the supports and interventions for students who are chronically absent at getting students back into school and keeping them there? Are different models more or less effective?

|

IDI |

|

Surveys of students, parents and whānau, Attendance Service staff, and schools |

|

|

Interviews with students, parents and whānau, Attendance Service staff, and schools |

|

|

What needs to change so that the supports and interventions for students who are chronically absent from school achieve better results and are cost-effective? |

Surveys of students, parents and whānau, Attendance Service staff, and schools |

|

Interviews with students, parents and whānau, Attendance Service staff, and schools |

Ethics

All participants were informed of the purpose of the evaluation before they agreed to participate in an interview. Participants were informed that:

- participation was voluntary and could be withdrawn at any time

- their words may be included in reporting, but no identifying details would be shared

- permission to use their information could be withdrawn at any time

- interviews were not an evaluation of their school, and their school or provider would not be identified in the resulting national report

- their information was confidential and would be kept securely subject to the provisions of the Official Information Act 1982, Privacy Act 1993, and the Public Records Act 2005 on the release and retention of information.

Interviewees consented to take part in an interview via email, or by submitting a written consent form to ERO. Their verbal consent was also sought to record their online interviews. Participants were given opportunities to query the evaluation team if they needed further information about the consent process.

Data collected from interviews, surveys, and administrative data will be stored digitally for a period of six months after the full completion of the evaluation. During this time, all data will be password-protected and have limited accessibility.

Quality assurance

The data in this report was subjected to a rigorous internal review process for both quantitative and qualitative data, which was carried out at multiple stages across the evaluation process. External data provided by the Ministry and SIA was reviewed by them.

5. The caveats for this report

Administrative attendance data

Administrative attendance records are comprehensive. They contain information on the attendance of students who are enrolled at schools in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The latest data on attendance used in this report is from Term 2, 2024.

Surveys

The surveys were focused on students who have been chronically absent and their parents and whānau. Responses are representative of chronically absent Māori and Pacific students, but are over representative of chronically absent Pākehā students (respondents were able to select multiple ethnicities). To ensure robustness, the survey results are complemented with administrative data, including Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) analysis, to draw conclusions.

Integrated Data Infrastructure

Data from the IDI is comprehensive. It contains information on attendance of students who are enrolled in Aotearoa New Zealand schools from 2011 onwards. However, the voices of young people who are not enrolled in school or do not attend school regularly are difficult to access. While we have captured some of their voices, the majority of students in our sample either attend school some of the time or have been successfully returned to education.

IDI data disclaimers

These results are not official statistics. They have been created for research purposes from the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) which is carefully managed by Stats NZ. For more information about the IDI please visit: https://www.stats.govt.nz/integrated-data/.

The results are based in part on tax data supplied by Inland Revenue to Stats NZ under the Tax Administration Act 1994 for statistical purposes. Any discussion of data limitations or weaknesses is in the context of using IDI for statistical purposes, and is not related to the data’s ability to support Inland Revenue’s core operational requirements.

6. Terminology

What is chronic absence?

There are four different categories of attendance, depending on how many half-days a student attends in a school term. These are set out below.

- Regular attendance: attend 90 percent or more of a term (missing up to five days of a 10-week term).

- Irregular absence: attend 80 to 90 percent of a term (missing five to 10 days of a 10-week term).

- Moderate absence: attend 70 to 80 percent of a term (missing 10 to 15 days of a 10-week term).

- Chronic absence: attend less than 70 percent of a term (missing 15 days or more of a 10-week term). This report focuses on this group of students.

What counts as ‘going to school’?

Students are present at school when they are in class. They are also considered present when they are:

- late to class (but within school policy for lateness)

- on the school site, doing things like:

- unsupervised study

- sitting an exam

- having an appointment at school (e.g., with a dean, sports coach, or nurse)

- waiting in the sickbay

- in-school isolation (e.g., removed to a different class or in the administration corridor) - away from school, but doing a school-based activity, like

- a sports trip or cultural presentation

- camp - learning somewhere else, as agreed with the school, like:

- Alternative Education, Secondary Tertiary Programme (including Trades Academies), or Activity Centre

- Teen Parent Unit, Health Camp, or Regional Health School

- a course or work experience - at a medical or dental appointment, or attending to Justice Court proceedings.

Different types of absences

Table 1: Justified and unjustified absences

|

Justified absence |

Unjustified absence |

|

Students are marked as having a ‘justified absence’ if they are away from school for:

- representing at a local or national level in a sporting or cultural event - bereavement - unplanned absences like extreme weather

Students are marked as being ‘overseas (justified)’ if they are accompanying or visiting a family member on an overseas posting, for up to 15 weeks. If it is longer than 15 weeks, their absence becomes unjustified. |

Students are marked as having an ‘unjustified absence’ if they:

|

Abbreviations

- IDI: The Integrated Data Infrastructure is a large research database maintained by Stats NZ. It holds de-identified microdata about people and households.

- ERO: Education Review Office

- The Ministry: Ministry of Education

- SIA: Social Investment Agency

- UE: Un-enrolled students

- UA: Unjustified absence

- N: Number of responses

7. Report structure

This report has 10 chapters.

- Chapter 1: Evaluation design

- Chapter 2: Analytical tools – Data and Methodology

- Chapter 3: How well attendance is going in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Chapter 4: What is driving chronic absence from school

- Chapter 5: The outcomes for students who are chronically absent

- Chapter 6: How effective the Aotearoa New Zealand model is against that evidence

- Chapter 7: How effective Attendance Services are

- Chapter 8: How effective schools are at addressing chronic absence

- Chapter 9: Our key findings and the areas for action to drive improvement in student attendance

- Chapter 10: Limitations of this research

Conclusion

ERO was commissioned to look at students who are chronically absent and the effectiveness of Attendance Services in bringing those students back to school. We used a mixed-methods approach, drawing on a wide range of administrative data, site visits, surveys, and interviews.

The next chapter describes the tools and analysis methods we used.

Chapter 2: Analytical tools - Data and methodology

This evaluation draws on a variety of data collected, using a mixed-methods approach to answer the evaluation questions. Sources of information include the Integrated Data Infrastructure, administrative data on attendance, analysis of chronically absent students, and survey responses from students, school leaders, Attendance Service staff, and parents and whānau.

This chapter sets out information about the tools used to collect this data, and how we brought together the multiple sources of information to assess the quality of the system that works to reduce chronic student absence in Aotearoa New Zealand schools.

This chapter describes our data collection methods, and the analytical techniques used in answering our evaluation questions presented in the previous chapter.

This chapter sets out our:

- overview of the approach

- data collection methods

- analysis methods.

1.Overview of the approach

We used a mixed-methods approach to collect the data to draw our findings. To make sense of our findings and recommendations, we drew on the knowledge of subject matter experts.

a) Mixed-methods approach to data collection

ERO used a mixed-methods approach, drawing on a wide range of administrative data, site visits, surveys, and interviews. This report draws on the voices of students, school leaders, Attendance Services, parents and whānau, and experts to understand chronic absence and its implications on the students in long term.

Our mixed-methods approach integrated quantitative data (IDI, administrative data, and surveys) and qualitative data (surveys, focus groups, and interviews) - triangulating the evidence across these different data sources. We used the triangulation process to test and refine our findings statements, allowing the weight of this collective data to form the conclusions. The rigour of the data and validity of these findings were further tested through iterative sense-making sessions with key stakeholders.

To ensure breadth in providing judgement on the key evaluation questions we used:

|

Surveys of: |

Two-thirds of Attendance Services |

154 |

|

Nearly 800 students with a history of chronic absence |

773, of which 256 were chronically absent in the last week |

|

|

Over 1000 parents and whānau of students with attendance issues |

1131, of which 311 had children who were chronically absent in the last week |

|

|

Nearly 300 school leaders |

276 |

|

|

Data from: |

IDI analysis |

|

|

Ministry data and statistics on attendance, and administrative data from Attendance Services |

||

|

Findings from the Ministry’s internal review of the management and support of the Attendance Service |

||

|

ERO’s evaluations of schools |

||

|

International evidence on effective practice in addressing chronic absence, including models from other jurisdictions |

||

To ensure depth in understanding of what works and what needs to improve we used:

|

Interviews and focus groups with: |

Attendance Service staff |

77 |

|

Students |

21 |

|

|

Parents and whānau |

26 |

|

|

School leaders |

79 |

|

|

Site-visits at: |

One-quarter of Attendance Services |

19 |

|

28 English-medium schools |

28 |

b) Sense-making through expert group discussions

Following analysis of the administrative data, surveys, and interviews, we conducted sense-making discussions to test interpretation of the results, findings, and areas for action with:

- ERO specialists in reviewing school practice

- the project’s Expert Advisory Group, made up of sector experts

- the project’s Steering Group, made up of ERO, the Ministry, and SIA representatives.

All three groups included Māori representation.

We then tested and refined the findings and lessons with the following groups to ensure they were useful and practical.

- Representatives from the Ministry and Social Investment Agency

- The project Steering Group

2. Data collection methods

We used data from existing and new data sources including:

- IDI

- surveys

- administrative attendance data

- interviews and focus groups

- international literature.

a) Use of Integrated Data Infrastructure

We worked with the SIA on this report. The SIA used the data in IDI to analyse:

- characteristics, predictors, and drivers of students who were chronically absent in 2019

- longer-term outcomes of students who are referred to the Attendance Service, compared to a group of similar students

- longer-term outcomes for a group of students with low attendance

- longer-term costs to the Government of students with low attendance.

b. Surveys

For the evaluation of the Attendance Service system, we administered surveys of:

- school leaders

- Attendance Service staff

- students who are chronically absent or have a history of chronic absence

- parents and whānau of chronically absent students.

Survey links for school leaders, students, and parents and whānau, were sent via email to schools to distribute. Survey links for Attendance Service staff, students, and parents and whānau were sent via email to Attendance Service providers to distribute.

Surveys were in the field from mid-June to early August 2024. All surveys were carried out using SurveyMonkey. The parent and whānau survey (with minor adaptions) was also distributed through Dynata.

Full surveys can be found in the appendices (Appendix 2).

Table 2: Sample size

|

Surveys |

Number of responses1 |

Time period |

|

Student |

773 |

16 June – 11 August |

|

School leaders |

276 |

16 June – 28 July |

|

Parents and whānau |

1,131 |

16 June – 22 July |

|

Attendance Services staff |

154 |

16 June – 28 July |

Number of usable, complete responses received and used in our analysis.

Student surveys

Participants were selected if they were chronically absent or had a history of chronic absence.

Links were sent in two tranches.

- Tranche 1: sent to 500 state schools across all regions – 150 secondary and composite, and 350 primary and intermediate. Sent to all Attendance Services.

- Tranche 2: sent to 300 additional schools to ensure there was good representation across characteristics (e.g., size, type, location etc.).

ERO also shared the survey links with the Ministry to share on their networks and through regional hubs, Te Aho o te Kura Pounamu (formerly The Correspondence School), alternative education providers, and other student support organisations. Participants who completed the parent and whānau survey were also invited to pass the survey link on to their children if they had not already completed one.

Attendance Services surveys

Participants for the Attendance Services survey are:

- staff who worked at Attendance Services (including advisors and officers)

- leaders/managers of Attendance Services.

School leader surveys

Participants were selected on the following criteria:

- school leaders and/or staff who dealt with attendance, in schools who had made at least one referral to their Attendance Service (Tranche 1)

- school leaders and/or staff in schools who dealt with attendance, who may or may not have referred students to their Attendance Service (Tranche 2).

We sent links to schools in two tranches.

- Tranche 1: sent to 500 state schools across all regions – 150 secondary and composite, and 350 primary and intermediate.

- Tranche 2: sent to 300 additional schools to ensure there was good representation across characteristics (e.g., size, type, location etc.).

ERO sent information and survey links to schools via email. After one week, ERO identified schools with no responses and re-engaged these schools via email.

Parent and whānau survey

Participants were selected if their child was currently chronically absent or had a history of chronic absence.

ERO sent links to 800 schools and all Attendance Services for them to share with parents and whānau of chronically absent students who they had been working with to increase their attendance.

c) Administrative attendance records data

The Ministry publishes data on student attendance on their website (Education Counts).2 In this report, we used the latest available data from Term 2, 2024. We analysed attendance patterns and trends of chronic absence from 2011 to 2024. A snapshot of this data can be found in Appendix 1. More detail can be found on the Ministry’s Education Counts website.

d) Site visits, interviews, and focus groups

The interviews and focus groups were conducted for students, school leaders, Attendance Service providers, and parents and whānau from April to May 2024. Most interviews were conducted during site visits. Some interviews were conducted online to better suit participants.

All interviews were carried out by members of the project team, which included evaluation partners who work directly with schools. Interviews were semi-structured, developed from domains and indicators developed from international and national literature, and refined through discussions with experts. Most interviews had two project team members. We conducted interviews with:

- twenty-one chronically absent young people who were nominated by schools and Attendance Services

- twenty-six parents and whānau who were nominated by schools and Attendance Services

- seventy-seven Attendance Service staff.

Site visits

We visited 28 schools and 19 Attendance Services, most of whom were selected in partnership with the Ministry from a list of 20 Attendance Services and 84 schools who had made a referral to Attendance Services in each region.

We made clear in all communication that:

- participation was voluntary

- consent is sought and anonymity is assured

- interviews and focus groups with students were undertaken with their agreement and parental consent (if under 16 years)

- interviews/focus groups could happen either online, over the phone, or in person.

e) International literature

We drew on international evidence to understand if the increasing trend in chronic absence is a global phenomenon, after Covid-19. International evidence has also been key in accessing how different other countries address chronic absence in schools, interventions, practices, and systems they have in place to support schools and students to attain high level of attendance.

Key sources of information were from research centres focused on attendance (e.g., Attendance Works, United States of America), and Department of Education resources in New South Wales, Australia, and the United Kingdom.

We also used meta-analyses and reviews of attendance research (e.g., Education Endowment Fund) to develop an understanding of trends, effectiveness of approaches, interventions, and practices.

3. Analysis methods

This chapter sets out how we analysed the data from:

- the IDI

- surveys

- administrative attendance data

- interviews and focus groups

- international literature.

a) Integrated Data Infrastructure Data analysis

We worked with the SIA to determine:

- the characteristics, predictors, and drivers of students who were chronically absent in 2019

- the longer-term outcomes of students who are referred to the Attendance Service, compared to a group of similar students

- longer-term outcomes for a group of students with low attendance

- longer-term costs to the Government of students with low attendance.

The characteristics, predictors, and the drivers of chronically absent students

The analysis looks at the characteristics of students who were chronically absent in Term 2, 2019. The sample included students who had attendance data in both Term 2 2018 and Term 2 2019, and were of compulsory school age (aged 5-15) in 2019.

Characteristics

The characteristics considered in the analysis include:

- whether student had chronic absence in 2018

- student has a record of recent offending of any crime in 2019

- student has a record of being a victim of crime in 2019

- mother/father (measured separately) having custodial or community sentences in 2019student living in social or emergency housing in 2019

- student received mental health and addiction services in 2019

- mother/father (measured separately) received mental health and addiction services in 2019

- student had a diagnosis of Intellectual Disability, Autism Spectrum Disorder, or had evidence (not necessarily diagnosis) of functional impairment

- mother’s highest qualification as of 2019

- student was admitted to the emergency department in 2019

- student had a record of participating in early childhood education in the past

- student was subject of an Oranga Tamariki investigation in 2019

- equivalised income in the household of the student in 2019

- size of the student’s household in 2019

- NZ Deprivation Index associated with the student’s address in 2019.

- The modelling also adjusted for demographic characteristics (gender, ethnicity and whether the student lived in Auckland).

Regression

Logistic regression analyses were used to statistically compare which characteristics are more likely for students with chronic absence, after adjusting for the effects of the other characteristics.

The snapshot of chronically absent students in 2019 in the sample is as shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Number and percentage of students by attendance categories in 2019

|

Category |

Number of students (n) |

Percentage of students (%) |

|

Regular |

379,560 |

60% |

|

Irregular |

156,342 |

25% |

|

Moderate |

54,768 |

9% |

|

Chronic |

42,576 |

7% |

|

All |

633,246 |

100% |

Note that students who did not have attendance records in 2018 and a small number of students who could not be matched to the IDI were not included in this analysis. This means these numbers will differ from the statistics officially reported by the Ministry of Education.

For all tests, results were treated as significant if the p-value was equal to or less than 0.05. All results presented in the report are unweighted.

The regression outputs are in Appendix 3.

The findings from this analysis can be found in Chapter 4.

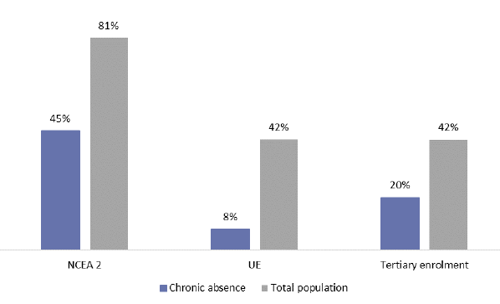

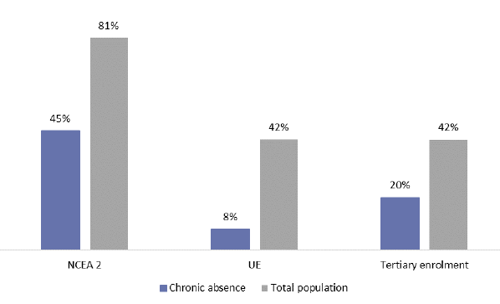

The outcomes for students with chronic absence

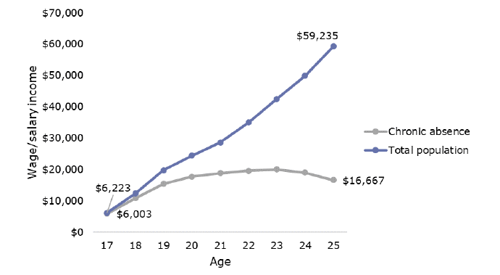

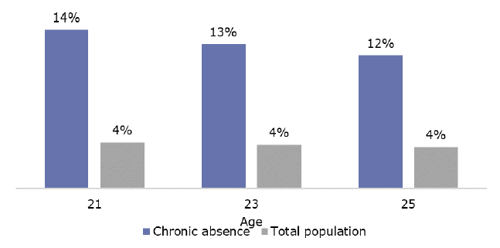

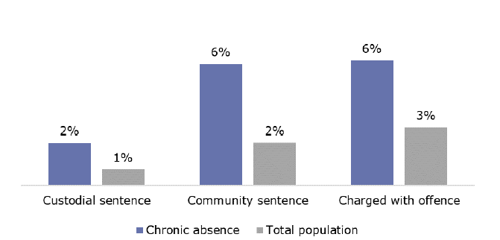

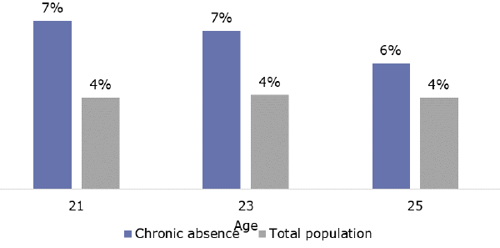

SIA analysed IDI data to identify students with chronic absence in Term 2 2019, born between 1990 and 2015. All students with attendance rates of 70 percent or less, irrespective of their enrollment status, are classified as chronically absent in this analysis. The analysis looks at the outcomes of chronically absent students in 2022.

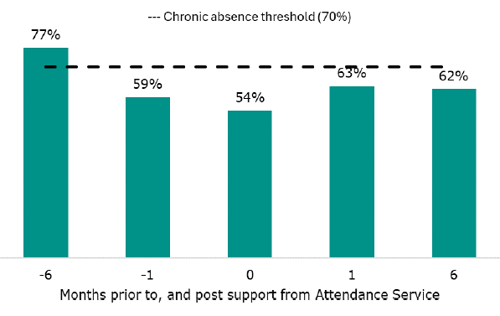

Longer-term outcomes of students who are referred to the Attendance Service

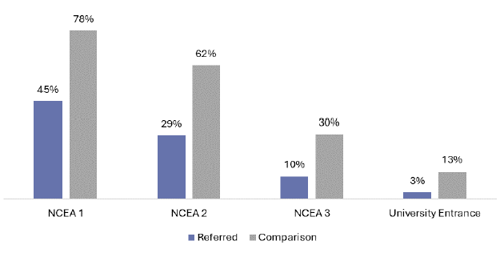

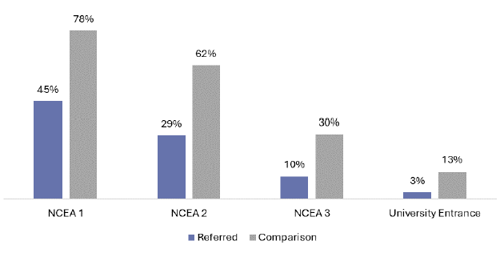

SIA looked at the population of people born between 1990 and 2015, and identified which of these people ever had a record of being referred to the Attendance Service (for chronic absence), and were aged 17 or older in 2022. These referred students were then paired with a comparison group (using Propensity Score Matching – more detail below) of otherwise similar students. Outcomes of both groups were then analysed, up to age 25.

The findings from this analysis can be found in Chapter 7.

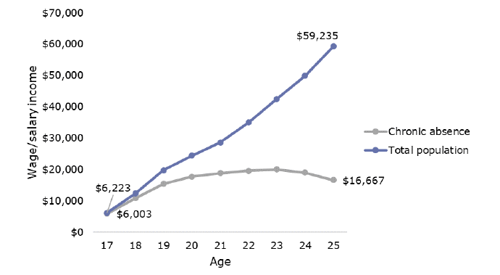

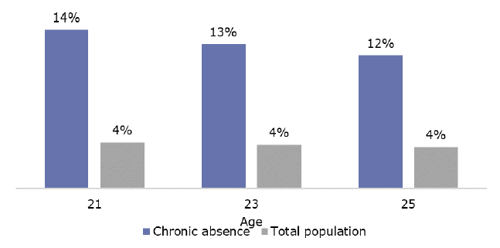

Outcomes

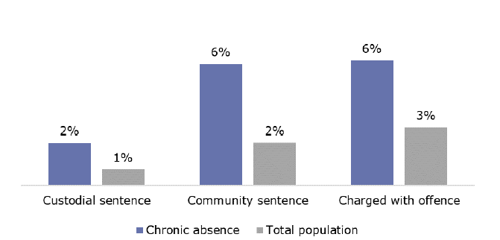

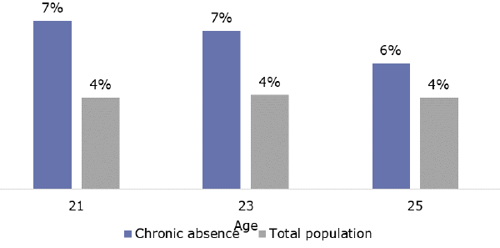

In this report, the outcomes are reported by age. The following outcomes were included for each age:

- education (highest school attainment)

- employment (whether IR recorded wage or salary income for the person)

- income (total income, including benefit income, recorded by IR)

- Government benefits received (whether IR recorded government benefit income)

- living in emergency housing (any spell during the year)

- rates of offending (Police proceeding in year)

- victims of a crime (reported victimisation to Police)

- corrections outcomes (any community or custodial sentence served during the year).

The analysis compares outcomes for chronically absent students and the total population for 17- to 25-year-olds. For example, we compared the proportion of 20-year-olds who were chronically absent who attained University Entrance to the proportion of 20-year-olds in the total population who attained University Entrance in 2022. The attendance data was not collected prior to 2011, therefore SIA could only follow young adults with a history of chronic absence through to age 25.

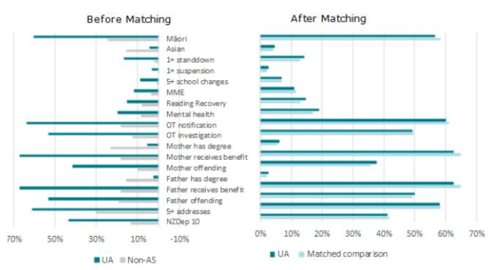

Comparison group and matching process

To carry out a comparative outcome analysis of chronically absent students who are not referred to the Attendance Services, SIA identified a comparative group using propensity score matching. The comparative group had similar circumstances and characteristics as chronically absent young people, but have never been referred to Attendance Services (see Appendix 4).

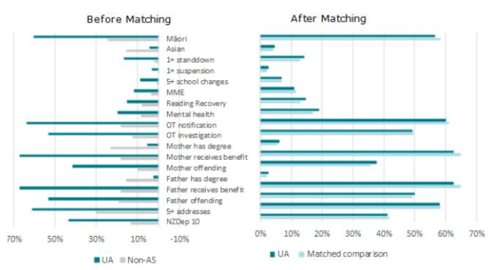

In total, 98 variables were used for matching, including age, ethnicity, stand-downs and suspensions, interactions with Oranga Tamariki and Youth Justice, and prior attendance history (see Appendix 4 for the full list of matching variables). The matching method was 1:1 nearest neighbour matching with replacement, using calipers for the overall propensity score as well as for justified and unjustified absence history. Referred students were exact matched on birth year and age and year of referral.

The matching process resulted in some referred students (for whom there was not a suitable non-referred counterpart) being dropped from the sample. Of the 62,154 students in the sample that were referred to the Attendance Service for chronic absence, 47,769 were included in the analysis. SIA undertook statistical tests comparing outcomes between the groups. All differences discussed in the report were statistically significant at the 5% level of significance.

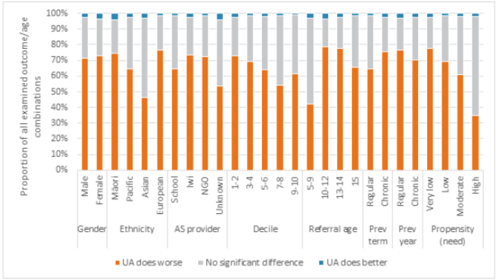

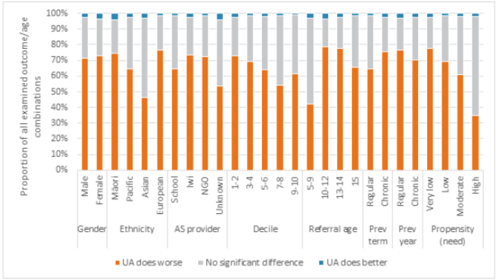

To ensure robustness in our conclusions, SIA also performed the same comparisons (between outcomes across the referred students and their matched comparison groups) for subsets of students of different genders, ethnicities, school deciles, referral ages, prior attendance, and of students attending different providers. There was no subset for which the Attendance Service group had detectably better outcomes than their matched comparison group (see figure 4C in Appendix 4).

There were a few unobserved factors which we could not control for in our analysis (e.g., bullying).

Longer-term outcomes for students with low attendance

For this analysis, SIA grouped the students who were referred to the Attendance Service due to chronic absence with the comparison group of students who were matched to these students. See the description of the previous analysis for more information on the sample used. These two groups combined are likely to represent a subset of the students who are chronically absent in any particular year.

Outcomes for this combined group of students with low attendance were compared with outcomes for the whole student population (matched using birth year but otherwise not adjusted for any other characteristic). No statistical tests were performed in this analysis.

The outcomes described in this section are the same as the outcomes used in the Attendance Service analysis.

The findings from this analysis can be found in Chapter 4.

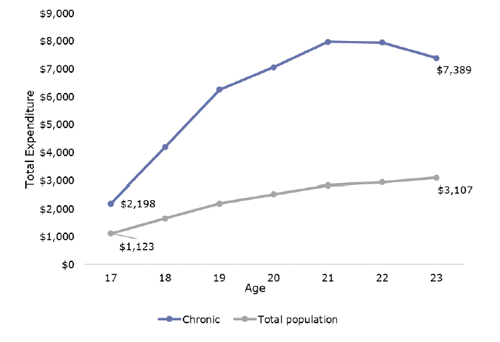

Costs to the Government for students with chronic absence

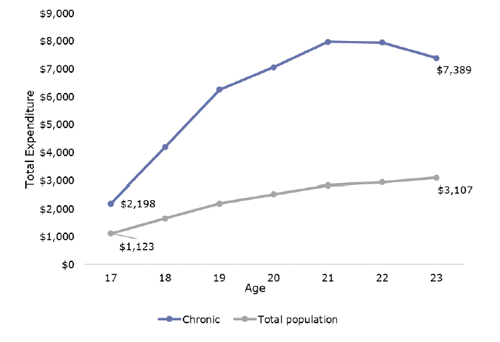

Using the same cohort as the previous analysis (the students who were referred to the Attendance Service due to chronic absence, combined with their counterparts in the matched comparison group), SIA examined the costs incurred through a subset of government services. Because cost data tends to be lagged in the IDI, this analysis tracked students from age 17 to age 23 (instead of age 25 as in the previous analysis).

The total Government expenditure includes expenditure on Ministry of Social Development benefits, costs associated with corrections (custodial and community sentences), public hospital admissions, pharmaceuticals costs, and disability support services expenses. The average Government expenditure was calculated for students with chronic absence by age, for 17- to 23-year-olds.

For comparison with the total population, average Government expenditure was calculated for all students by age 17 to 23 in 2022. The results from the analysis are discussed in Chapter 4: What are the outcomes for chronically absent students? in the section: What is the cost of these outcomes?.

b) Survey analysis

Surveys were given to students who were currently chronically absent and who had a history of chronic absence. The student dataset was used to identify the key reasons why students who are chronically absent miss school. We also used it to understand how students worked with schools and attendance services. Open ended questions were reviewed to see if there were reasons for chronic absence not included in the short answer questions.

Students

From the surveys we identified students who were chronically absent the week before. We used the two groups of students – those who were chronically absent last week and those with a history of chronic absence to look at the key drivers of the students who are currently chronically absent. We reported on the reasons for absence for the students who are currently chronically absent. To ensure our findings reflected current, rather than historical issues.

Parents

Like the students, surveys were given to parents of students who were currently chronically absent and who had a history of chronic absence. The parents dataset was used to identify the key reasons why their child misses school. We also used it to understand how parents worked with schools and attendance services. Open ended questions were reviewed to see if there were reasons for chronic absence not included in the short answer questions.

From the surveys we identified parents of students who were chronically absent the week before. We reported on the reasons for absence for the parents whose students who are currently chronically absent to ensure our findings reflect current, rather than historic issues.

The survey questions were designed to understand:

- why students are absent

- how effective the supports and interventions are for chronically absent students at getting them back to school and keeping them in school

- which model is more effective

- what needs to change so that the supports and interventions for chronically absent students achieve better results while being cost-effective.

Three analytical techniques were employed to analyse survey data:

- descriptive statistics

- regression analysis

- long answer analysis.

The quantitative data from surveys presented in this report is largely descriptive, but two regression analyses were run which assessed:

- what are the most likely reasons for the students to be chronically absent

- how different practices in schools impact levels of chronic absence.

Descriptive statistics

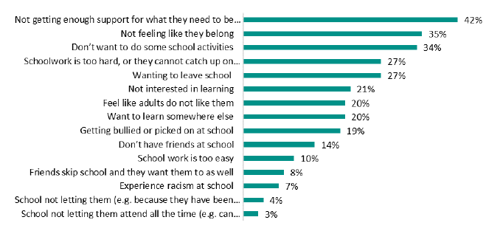

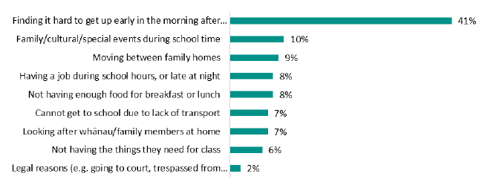

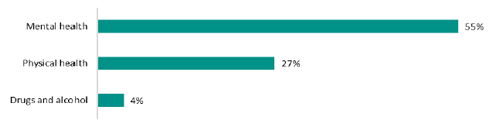

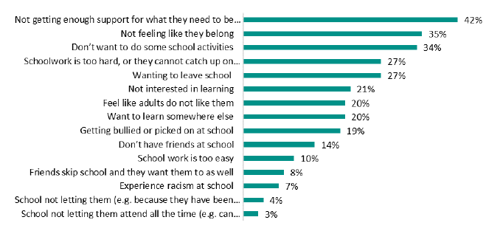

We completed quantitative survey data analysis to identify the key drivers/reasons for chronic absence from the viewpoint of students, school leaders, Attendance Service staff, and parents and whānau. We grouped main drivers into three categories: school factors, family factors, and student factors. We have reported on the proportion of respondents who have identified reasons in those categories as the key drivers for chronic absence.

Table 4: School factors

|

I can’t get enough support for what I need, to be at school |

I didn’t want to do some school activities (e.g. sports, maths etc) |

My schoolwork is too hard, or I can’t catch up on work I have missed |

|

I don’t feel like I belong at school |

My schoolwork is too easy |

I am not interested in learning |

|

I want to leave school |

I want to learn somewhere else |

I feel like adults at school don’t like me |

|

The school does not let me attend all the time (e.g. can only attend school with a support person) |

The school won’t let me (e.g. because I have been stood down or suspended) |

I don’t have friends at school |

|

My friends skip school and want me to as well |

I get bullied or picked on at school |

I feel people at school behave in racist ways towards me |

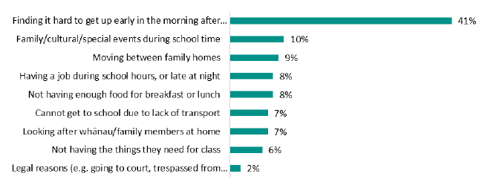

Table 5: Family factors

|

I move between family members or homes |

It is hard to get up early in the morning when I have stayed up late (e.g., playing video games, watching a movie, or my house is too noisy) |

I have a job I work at during school hours, or late at night |

|

I have to look after whānau/family members at home |

I had lots of whānau/family/cultural/special events during school time (e.g. funerals or tangihanga, weddings, overseas travel) |

I can't get to school (no bus, car) |

|

I don’t have enough food for breakfast or lunch |

I don't have the things I need for class (e.g. school uniform, books, device, bag) |

Legal reasons (e.g. I have to go to court, or I’m trespassed from school) |

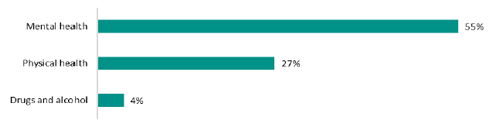

Table 6: Student factors

|

My physical health (including long-term health issues or period pain) |

Using drugs or alcohol gets in the way |

My mental health, including anxiety |

The findings from this analysis are discussed in Chapter 4: What is driving chronic absence?

Regression analysis

We ran two regression analyses looking at reasons chronically absent students do not attend school and effective approaches to reduce chronic absence.

Regression: Reasons for chronic absence

In the first regression analysis, we looked at the most likely reasons for chronically absent students not to attend school when we controlled for the impact of various demographic factors.

Sample

A logistic regression was run using survey data of 624 students.

The outcome variable of interest was the student who had been away from school more than two days in the last two weeks of Term 2.

There were 256 students who had been away for more than two days compared to 279 students who had been away for zero or one day. One hundred and fifty students were excluded from the regression analysis because they did not know or did not answer the question.

Variables

Predictor variables included in the model were:

- demographics: gender, ethnicity, disability, and if they are in the care of Oranga Tamariki

- school classification: whether they attended a primary or secondary school, the size of the school, Equity Index Score of schools, whether the school is in Auckland, the rest of the North Island, or the South Island, and the proportion of their school roll that has Māori or Pacific students

- behaviour and attitudes related survey questions: what school supports the student feel helped them get to school, reasons why they have not gone to school this year, and how important they feel school is for their future

- survey questions: the statements from the student survey on:

- Question 34: “what has helped you go to school more”

- Questions 24-29: “so far this year you did not go to school because…”.

The regression output can be found in appendix 3A.

Regression: Effective practices to reduced chronic absence

In the second regression analysis we looked at the key frameworks/approaches schools use to address chronic absence and the likelihood of those approaches to be successful in reducing chronic absence when we control for the impact of various demographic and socio-economic factors.

Sample

A logistic regression was run on the survey data of 255 school leaders.

The outcome variable of interest was the schools with less than 5 percent of students chronically absent.

In our sample, 142 schools had more than 5 percent of chronic absence and the remaining 113 schools had less than 5 percent of students chronically absent.

Variables

A number of predictor variables were included in the model.

- School classification: Primary or secondary school, the size of the school, Equity Index Score of schools, the proportion of their school roll that had Māori or Pacific students, and isolation index.

- Behaviour and attitudes related questions: How schools work with Attendance Services staff, how schools work with others to address attendance issues, the actions schools take to manage absence, the experience of schools with Attendance Services.

- Survey questions: From the school leader survey, the following questions:

- Question 17: “How do you work with Attendance Services staff”

- Question 32: “How much you agree with the statements, thinking about how you work with others to address attendance issues….”

- Question 33: “How often the school staff do the actions below….”

- Question 38: “How much do you agree with the questions, thinking about the attendance environment and the staff working in it….”

- Question 39: “How often the staff working to support attendance do the actions below….”.

Detail on the regression can be found in appendix 3B.

Long answer questions

We used the open-ended responses from our surveys to understand the effectiveness of Attendance Services, and to find out which approaches are effective in successfully returning chronically absent students to school.

The open-ended questions used in our surveys are outlined below.

For students:

- What has helped you go to school more?

- What did teachers, school leaders and Attendance Service workers/officers do that got in the way of helping you attend school more? Why didn’t it help?

- What would help you go to school more?

For parents and whānau:

- What has helped your child go to school more?

- What did not work well when working with school and Attendance Service staff to help your child go to school more?

- What would help your child go to school more?

For Attendance Service staff:

- In your experience, what does work to increase attendance? Why do you think this does work?

- In your experience, what does not work to increase attendance? Why do you think this does not work?

- Do you have any more comments about student attendance/lack of attendance in NZ schools?

For school leaders:

- What has helped students come to school more?

- In your experience, what does work to increase attendance? Why do you think this does work?

- In your experience, what does not work to increase attendance? Why do you think this does not work?

- Do you have any more comments about student attendance/lack of attendance in NZ schools?

c) Administrative attendance data analysis

The Ministry publishes data on attendance of students for each term (Education Counts). 3 In this report, the latest available data from Term 2, 2024 is used. We looked at attendance patterns and the trend of chronic absence from 2011. We used this data to analyse our evaluation question, “Who are the students who are chronically absent from school?”.

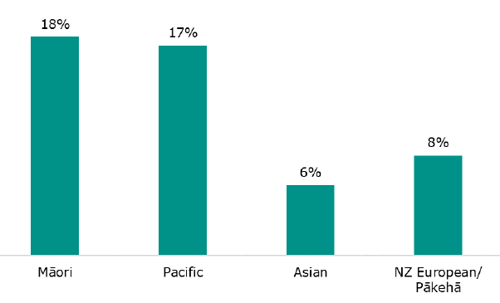

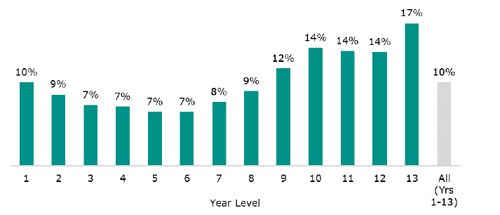

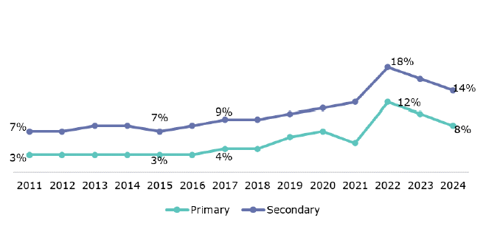

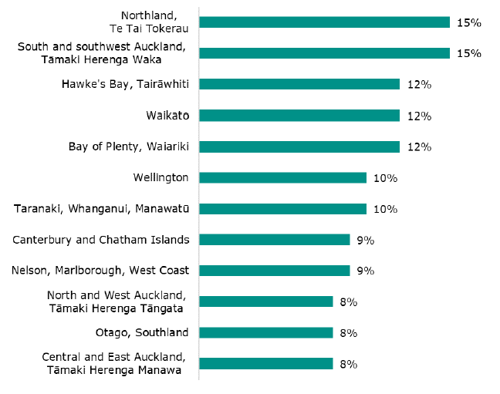

We analysed demographic cuts like gender, ethnicities, region, year-level, and school type. We also used attendance data from the Ministry to look at the patterns of attendance by schools.

The quantitative data presented in this report, using administrative attendance records, is largely descriptive statistics.

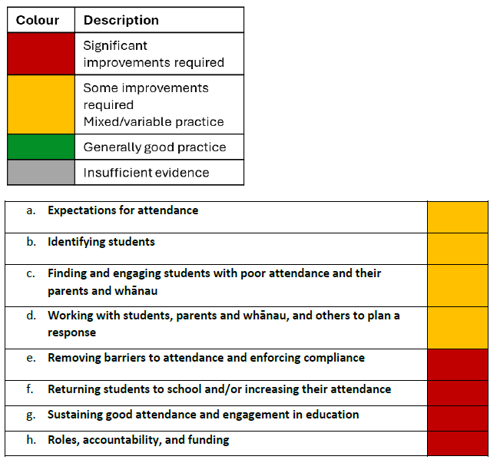

d) Site visits, interviews, and focus groups analysis

The interviews were guided using semi-structured questions that were developed from domains and indicators on good practice in schools and Attendance Services. Based on analysis of key documents and interviews with key staff, the evaluation team assessed the quality of provision against the domains set out in Chapter 6. This assessment led to a description of how the Attendance Service and school was performing on each domain and indicator. This helped the evaluation team identify examples of good practice and to understand what the key contributing factors were. Similarly, the team was able to identify examples of issues and challenges that Attendance Services and schools were facing and understand the main contributing factors.

Questions we asked:

For students:

- Do you think coming to school is important?

- What are some good things about coming to school?

- What are some of the reasons you might not come to school?

- What might help you attend school more often?

- Talk to us through what happened when you did not attend school

- What worked well? What did not?

For parents and whānau:

- Please tell me a bit about yourself.

- Do you think attending school is important?

- What are some of the reasons your child might not come to school?

- What could help your child attend school more often?

- Talk to us through how your child got support when they did not attend school

- What worked well?

For school leaders and staff with attendance responsibilities:

- Talk to us about what your role involves.

- Tell us about attendance patterns or issues at your school.

- How does your school deal with any attendance challenges?

- Considering the last year, what would you say is the percentage of students who:

- returned to school?

- increased their attendance?

- stayed at school?

- Have you accessed the Regional Response Fund (RRF)?

- What could make a difference in helping you to address chronic absence?

For Attendance Services managers/leaders:

- Talk to us about what your role involves .

- Are there any patterns or trends in attendance across the cluster?

- How do you work with students and their families? How do you work with schools?

- Have you been involved with a project resourced from the Regional Response Fund (RRF)? Considering the last year, what would you say is the percentage of students who:

- returned to school?

- increased their attendance?

- stayed at school?

- What could make a difference in helping you to address chronic absence?

Analysis

Data was analysed in two main ways.

- A semi-inductive approach was initially taken, whereby the interviewer notation was coded into previously established themes, which were organised within the key evaluation questions. Cross-interview themes were established during workshops comprising the qualitative analysis team.

- Following substantive analysis of both the qualitative and quantitative data, a deductive approach was taken to establish exemplars that illustrated those analyses with real-world experiences.

The research team held workshops to discuss the survey data and the interview results to identify cross-cutting themes. This also ensured that members of the research team were analysing and interpreting the data consistently, and additional investigation could be undertaken to address gaps or inconsistencies.

We used information from interviews and focus groups to answer our evaluation questions:

- Why are students absent?

- How effective are the supports and interventions for students who are chronically absent at getting students back into school and keeping them in school?

- Are different models more or less effective?

- What needs to change so that the supports and interventions for students who are chronically absent from school achieve better results and are cost-effective?

All quotes were gathered from verbatim records and open-ended survey responses.

Conclusion

This evaluation developed numerous data collection tools and methods of analysis to answer key evaluation questions about chronically absent students and the system of support available to them.

In the next chapter, we describe how we looked at the extent of the problem of chronic absence in Aotearoa New Zealand.

This evaluation draws on a variety of data collected, using a mixed-methods approach to answer the evaluation questions. Sources of information include the Integrated Data Infrastructure, administrative data on attendance, analysis of chronically absent students, and survey responses from students, school leaders, Attendance Service staff, and parents and whānau.

This chapter sets out information about the tools used to collect this data, and how we brought together the multiple sources of information to assess the quality of the system that works to reduce chronic student absence in Aotearoa New Zealand schools.

This chapter describes our data collection methods, and the analytical techniques used in answering our evaluation questions presented in the previous chapter.

This chapter sets out our:

- overview of the approach

- data collection methods

- analysis methods.

1.Overview of the approach

We used a mixed-methods approach to collect the data to draw our findings. To make sense of our findings and recommendations, we drew on the knowledge of subject matter experts.

a) Mixed-methods approach to data collection

ERO used a mixed-methods approach, drawing on a wide range of administrative data, site visits, surveys, and interviews. This report draws on the voices of students, school leaders, Attendance Services, parents and whānau, and experts to understand chronic absence and its implications on the students in long term.

Our mixed-methods approach integrated quantitative data (IDI, administrative data, and surveys) and qualitative data (surveys, focus groups, and interviews) - triangulating the evidence across these different data sources. We used the triangulation process to test and refine our findings statements, allowing the weight of this collective data to form the conclusions. The rigour of the data and validity of these findings were further tested through iterative sense-making sessions with key stakeholders.

To ensure breadth in providing judgement on the key evaluation questions we used:

|

Surveys of: |

Two-thirds of Attendance Services |

154 |

|

Nearly 800 students with a history of chronic absence |

773, of which 256 were chronically absent in the last week |

|

|

Over 1000 parents and whānau of students with attendance issues |

1131, of which 311 had children who were chronically absent in the last week |

|

|

Nearly 300 school leaders |

276 |

|

|

Data from: |

IDI analysis |

|

|

Ministry data and statistics on attendance, and administrative data from Attendance Services |

||

|

Findings from the Ministry’s internal review of the management and support of the Attendance Service |

||

|

ERO’s evaluations of schools |

||

|

International evidence on effective practice in addressing chronic absence, including models from other jurisdictions |

||

To ensure depth in understanding of what works and what needs to improve we used:

|

Interviews and focus groups with: |

Attendance Service staff |

77 |

|

Students |

21 |

|

|

Parents and whānau |

26 |

|

|

School leaders |

79 |

|

|

Site-visits at: |

One-quarter of Attendance Services |

19 |

|

28 English-medium schools |

28 |

b) Sense-making through expert group discussions

Following analysis of the administrative data, surveys, and interviews, we conducted sense-making discussions to test interpretation of the results, findings, and areas for action with:

- ERO specialists in reviewing school practice

- the project’s Expert Advisory Group, made up of sector experts

- the project’s Steering Group, made up of ERO, the Ministry, and SIA representatives.

All three groups included Māori representation.

We then tested and refined the findings and lessons with the following groups to ensure they were useful and practical.

- Representatives from the Ministry and Social Investment Agency

- The project Steering Group

2. Data collection methods

We used data from existing and new data sources including:

- IDI

- surveys

- administrative attendance data

- interviews and focus groups

- international literature.

a) Use of Integrated Data Infrastructure

We worked with the SIA on this report. The SIA used the data in IDI to analyse:

- characteristics, predictors, and drivers of students who were chronically absent in 2019

- longer-term outcomes of students who are referred to the Attendance Service, compared to a group of similar students

- longer-term outcomes for a group of students with low attendance

- longer-term costs to the Government of students with low attendance.

b. Surveys

For the evaluation of the Attendance Service system, we administered surveys of:

- school leaders

- Attendance Service staff

- students who are chronically absent or have a history of chronic absence

- parents and whānau of chronically absent students.

Survey links for school leaders, students, and parents and whānau, were sent via email to schools to distribute. Survey links for Attendance Service staff, students, and parents and whānau were sent via email to Attendance Service providers to distribute.

Surveys were in the field from mid-June to early August 2024. All surveys were carried out using SurveyMonkey. The parent and whānau survey (with minor adaptions) was also distributed through Dynata.

Full surveys can be found in the appendices (Appendix 2).

Table 2: Sample size

|

Surveys |

Number of responses1 |

Time period |

|

Student |

773 |

16 June – 11 August |

|

School leaders |

276 |

16 June – 28 July |

|

Parents and whānau |

1,131 |

16 June – 22 July |

|

Attendance Services staff |

154 |

16 June – 28 July |

Number of usable, complete responses received and used in our analysis.

Student surveys

Participants were selected if they were chronically absent or had a history of chronic absence.

Links were sent in two tranches.

- Tranche 1: sent to 500 state schools across all regions – 150 secondary and composite, and 350 primary and intermediate. Sent to all Attendance Services.

- Tranche 2: sent to 300 additional schools to ensure there was good representation across characteristics (e.g., size, type, location etc.).

ERO also shared the survey links with the Ministry to share on their networks and through regional hubs, Te Aho o te Kura Pounamu (formerly The Correspondence School), alternative education providers, and other student support organisations. Participants who completed the parent and whānau survey were also invited to pass the survey link on to their children if they had not already completed one.

Attendance Services surveys

Participants for the Attendance Services survey are:

- staff who worked at Attendance Services (including advisors and officers)

- leaders/managers of Attendance Services.

School leader surveys

Participants were selected on the following criteria:

- school leaders and/or staff who dealt with attendance, in schools who had made at least one referral to their Attendance Service (Tranche 1)

- school leaders and/or staff in schools who dealt with attendance, who may or may not have referred students to their Attendance Service (Tranche 2).

We sent links to schools in two tranches.

- Tranche 1: sent to 500 state schools across all regions – 150 secondary and composite, and 350 primary and intermediate.

- Tranche 2: sent to 300 additional schools to ensure there was good representation across characteristics (e.g., size, type, location etc.).

ERO sent information and survey links to schools via email. After one week, ERO identified schools with no responses and re-engaged these schools via email.

Parent and whānau survey

Participants were selected if their child was currently chronically absent or had a history of chronic absence.

ERO sent links to 800 schools and all Attendance Services for them to share with parents and whānau of chronically absent students who they had been working with to increase their attendance.

c) Administrative attendance records data

The Ministry publishes data on student attendance on their website (Education Counts).2 In this report, we used the latest available data from Term 2, 2024. We analysed attendance patterns and trends of chronic absence from 2011 to 2024. A snapshot of this data can be found in Appendix 1. More detail can be found on the Ministry’s Education Counts website.

d) Site visits, interviews, and focus groups

The interviews and focus groups were conducted for students, school leaders, Attendance Service providers, and parents and whānau from April to May 2024. Most interviews were conducted during site visits. Some interviews were conducted online to better suit participants.

All interviews were carried out by members of the project team, which included evaluation partners who work directly with schools. Interviews were semi-structured, developed from domains and indicators developed from international and national literature, and refined through discussions with experts. Most interviews had two project team members. We conducted interviews with:

- twenty-one chronically absent young people who were nominated by schools and Attendance Services

- twenty-six parents and whānau who were nominated by schools and Attendance Services

- seventy-seven Attendance Service staff.

Site visits

We visited 28 schools and 19 Attendance Services, most of whom were selected in partnership with the Ministry from a list of 20 Attendance Services and 84 schools who had made a referral to Attendance Services in each region.

We made clear in all communication that:

- participation was voluntary

- consent is sought and anonymity is assured

- interviews and focus groups with students were undertaken with their agreement and parental consent (if under 16 years)

- interviews/focus groups could happen either online, over the phone, or in person.

e) International literature

We drew on international evidence to understand if the increasing trend in chronic absence is a global phenomenon, after Covid-19. International evidence has also been key in accessing how different other countries address chronic absence in schools, interventions, practices, and systems they have in place to support schools and students to attain high level of attendance.

Key sources of information were from research centres focused on attendance (e.g., Attendance Works, United States of America), and Department of Education resources in New South Wales, Australia, and the United Kingdom.

We also used meta-analyses and reviews of attendance research (e.g., Education Endowment Fund) to develop an understanding of trends, effectiveness of approaches, interventions, and practices.

3. Analysis methods

This chapter sets out how we analysed the data from:

- the IDI

- surveys

- administrative attendance data

- interviews and focus groups

- international literature.

a) Integrated Data Infrastructure Data analysis

We worked with the SIA to determine:

- the characteristics, predictors, and drivers of students who were chronically absent in 2019

- the longer-term outcomes of students who are referred to the Attendance Service, compared to a group of similar students

- longer-term outcomes for a group of students with low attendance

- longer-term costs to the Government of students with low attendance.

The characteristics, predictors, and the drivers of chronically absent students

The analysis looks at the characteristics of students who were chronically absent in Term 2, 2019. The sample included students who had attendance data in both Term 2 2018 and Term 2 2019, and were of compulsory school age (aged 5-15) in 2019.

Characteristics

The characteristics considered in the analysis include:

- whether student had chronic absence in 2018

- student has a record of recent offending of any crime in 2019

- student has a record of being a victim of crime in 2019

- mother/father (measured separately) having custodial or community sentences in 2019student living in social or emergency housing in 2019

- student received mental health and addiction services in 2019

- mother/father (measured separately) received mental health and addiction services in 2019

- student had a diagnosis of Intellectual Disability, Autism Spectrum Disorder, or had evidence (not necessarily diagnosis) of functional impairment

- mother’s highest qualification as of 2019

- student was admitted to the emergency department in 2019

- student had a record of participating in early childhood education in the past

- student was subject of an Oranga Tamariki investigation in 2019

- equivalised income in the household of the student in 2019

- size of the student’s household in 2019

- NZ Deprivation Index associated with the student’s address in 2019.

- The modelling also adjusted for demographic characteristics (gender, ethnicity and whether the student lived in Auckland).

Regression

Logistic regression analyses were used to statistically compare which characteristics are more likely for students with chronic absence, after adjusting for the effects of the other characteristics.

The snapshot of chronically absent students in 2019 in the sample is as shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Number and percentage of students by attendance categories in 2019

|

Category |

Number of students (n) |

Percentage of students (%) |

|

Regular |

379,560 |

60% |

|

Irregular |

156,342 |

25% |

|

Moderate |

54,768 |

9% |

|

Chronic |

42,576 |

7% |

|

All |

633,246 |

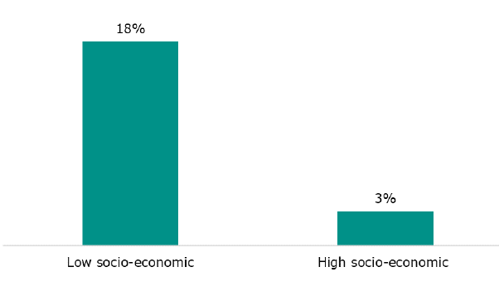

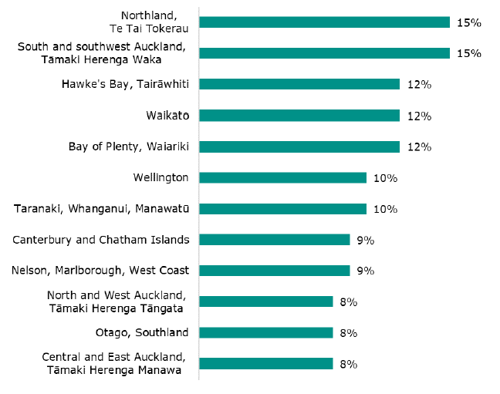

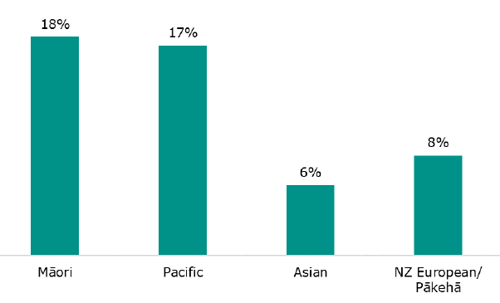

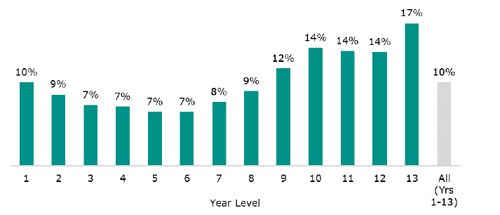

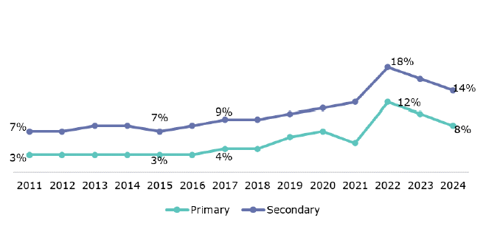

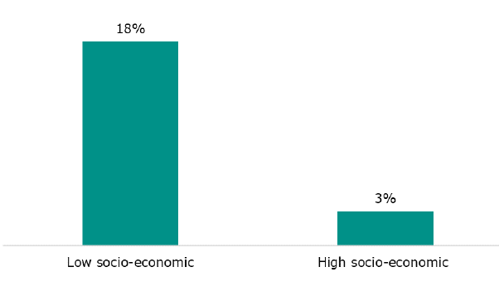

100% |