Related insights

Explore related documents that you might be interested in.

Read Online

Executive summary

Good classroom behaviour is critical for creating learning environments in which students can learn and achieve, and teachers can be most effective. But ensuring positive behaviour isn’t just up to schools – it requires shared responsibility and deliberate, joint actions.

This report describes the challenging behaviours teachers face in schools, the impact of those behaviours, and recommendations for action. Our companion good practice report also shares examples of how teachers and schools can effectively manage behaviour.

Behaviour in schools impacts on learning

Classroom behaviour impacts the learning of all students. Maintaining good behaviour in school classrooms is crucial for creating an environment where students can learn and achieve. In classes with positive behaviour, teachers are able to better use their time teaching, and less time reacting to and managing behaviours. This places far less strain on their health and enjoyment of the job, allowing them to teach at their best. For students, better behaviour in classrooms means less disruptions, allowing them to focus on learning.

ERO has looked at the behaviour in classrooms in Aotearoa New Zealand and how this is changing

This evaluation report sets out what ERO has found about behaviour in classrooms and the impact of behaviour on students and teachers. The companion good practice report shares practical strategies for teachers and leaders to support improvements in managing challenging behaviour in their schools.

Key findings

1. Behaviour is a major problem in Aotearoa New Zealand schools, and it is worse than other countries.

- Half of teachers have to deal with students calling out and distracting others in every lesson.

- A quarter of principals see students physically harming others and damaging or taking property every day.

- PISA results over the last 20 years show that Aotearoa New Zealand’s classrooms have consistently had worse behaviour compared to most other OECD countries. For example, Aotearoa New Zealand is lowest among OECD for behaviour in maths classes and in the bottom quarter of PISA countries for behaviour in English classes.

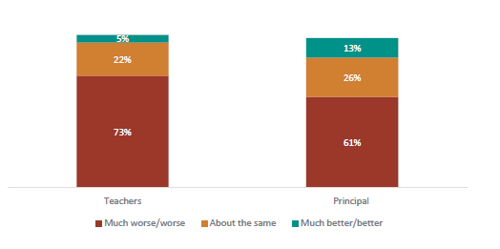

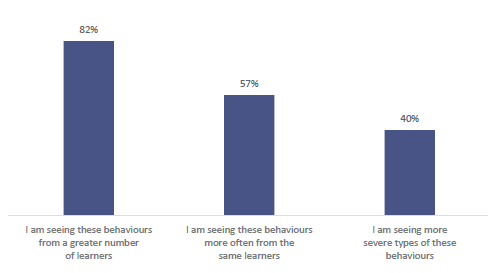

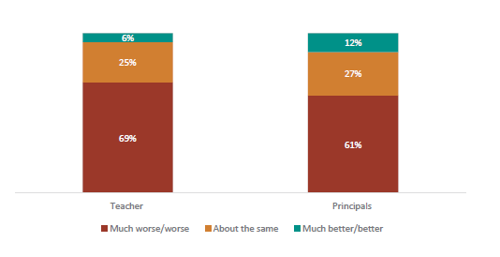

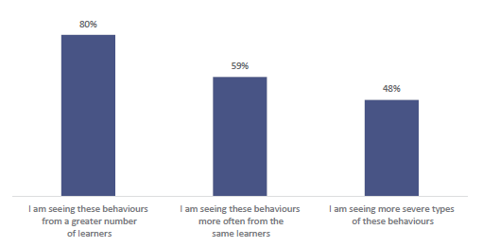

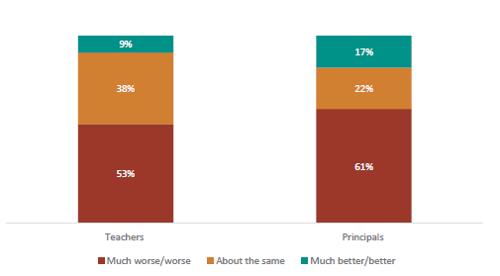

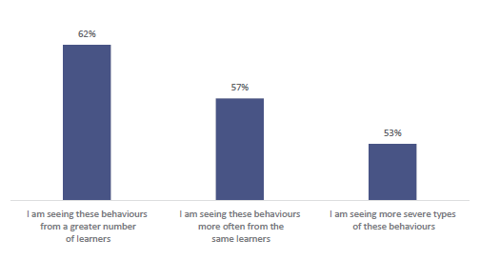

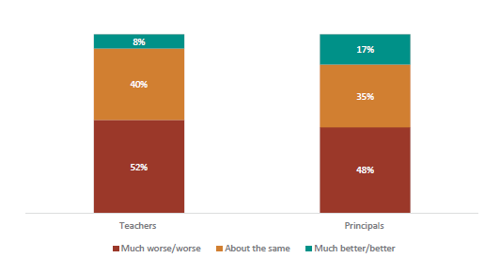

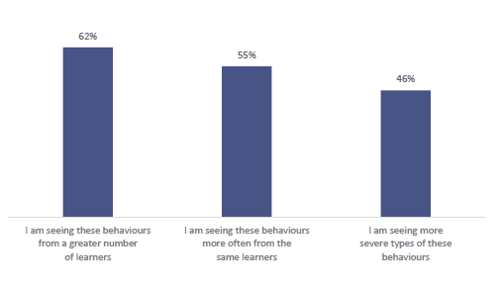

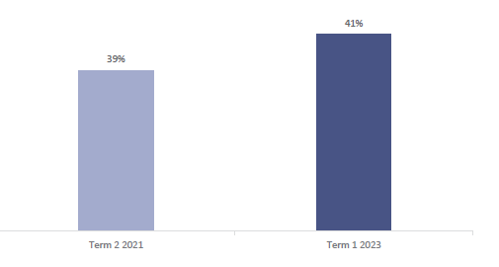

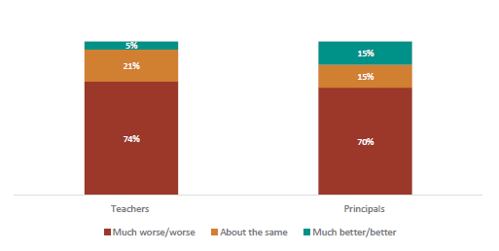

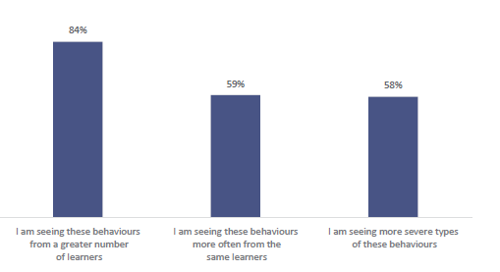

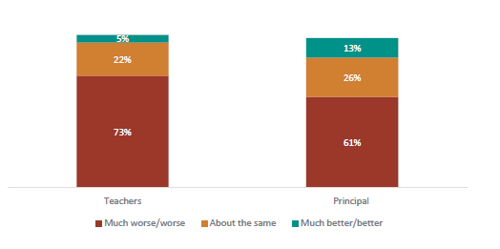

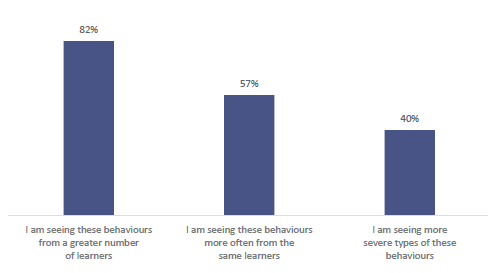

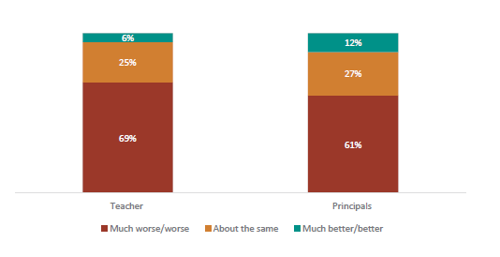

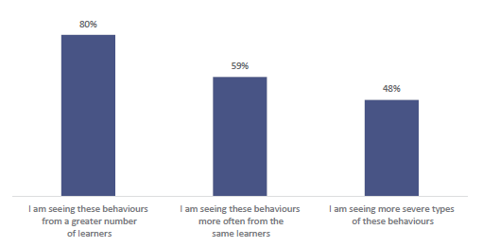

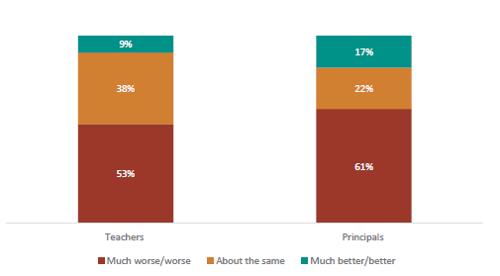

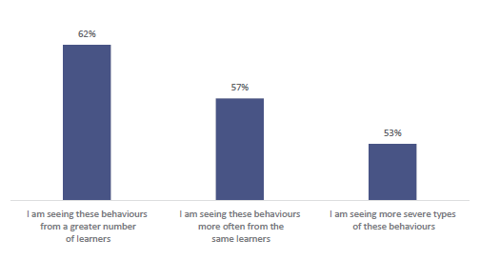

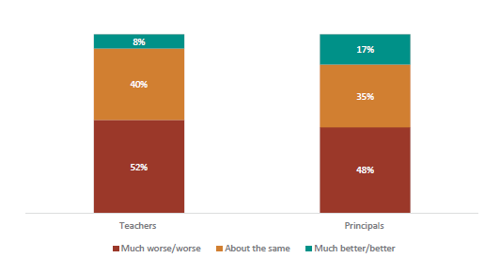

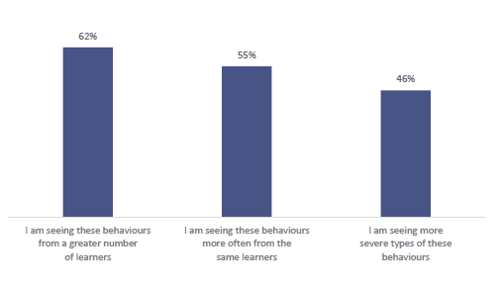

2. Student behaviour has become worse in the last two years.

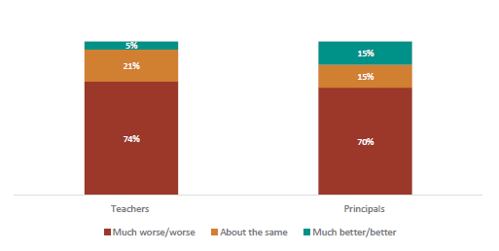

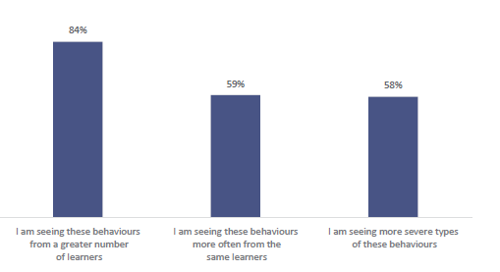

- Over half of teachers report all types of behaviour have become worse. In particular, they report a greater number of students displaying challenging behaviour.

3. Behaviour is significantly damaging student learning and achievement.

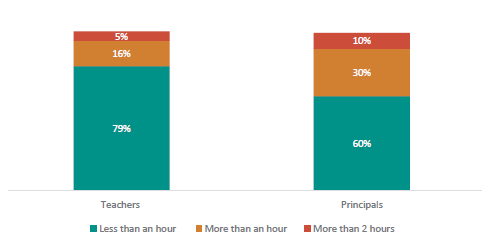

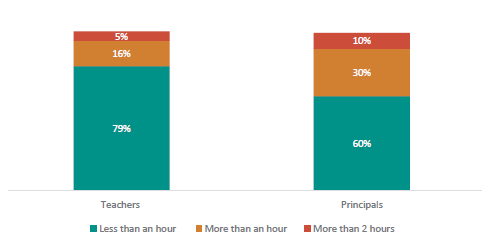

- Almost half (47 percent) of teachers spend 40-50 mins a day or more responding to challenging behaviour. This limits the time available to teach.

- Three-quarters of teachers believe student behaviour is impacting on students’ progress.

- International evidence (PISA) links behaviour and achievement, finding students in the most well-behaved maths classes scored significantly higher than all other students, and students in the worst-behaved classes scored the lowest.

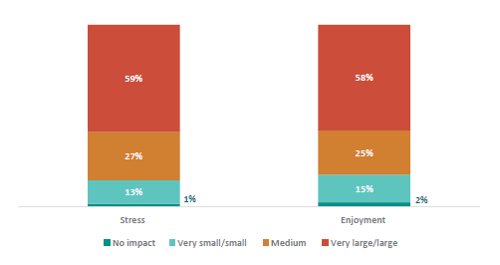

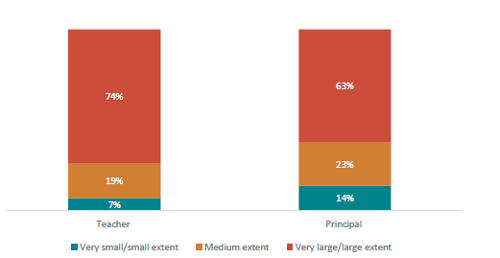

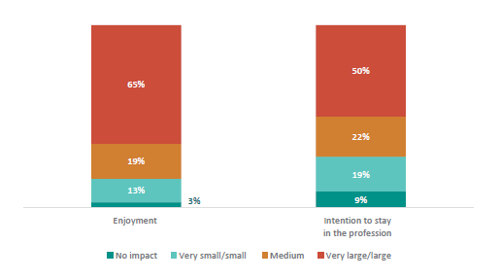

4. Behaviour is significantly impacting student enjoyment of school and therefore attendance.

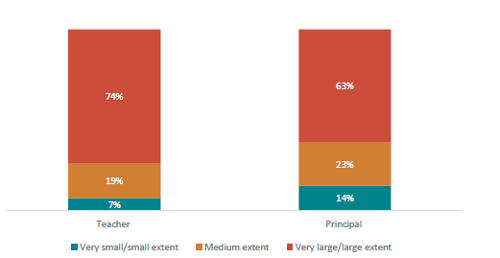

- Two-thirds of teachers (68 percent) and principals (63 percent) find that challenging behaviour in the classroom has a large impact on student enjoyment. Enjoyment of school is a key driver of attendance.

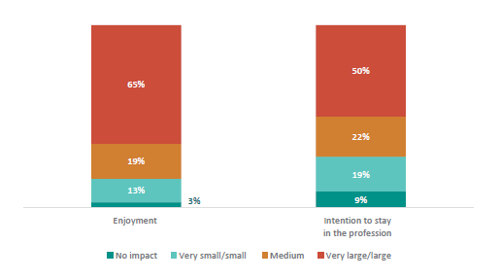

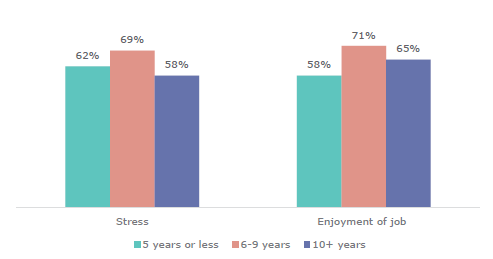

5. Behaviour is a key driver of teachers leaving teaching.

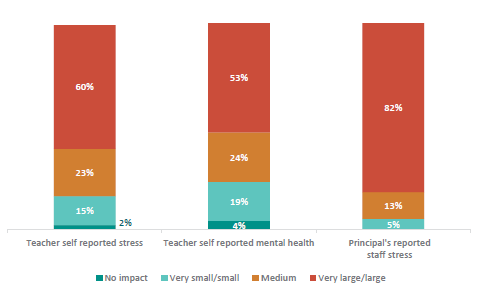

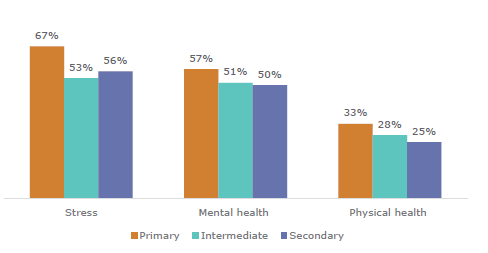

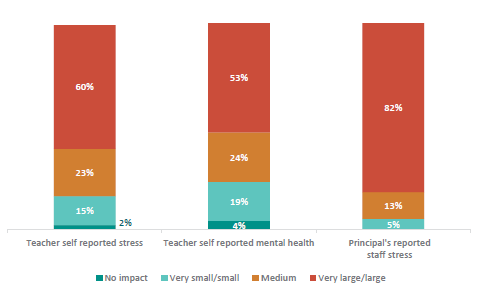

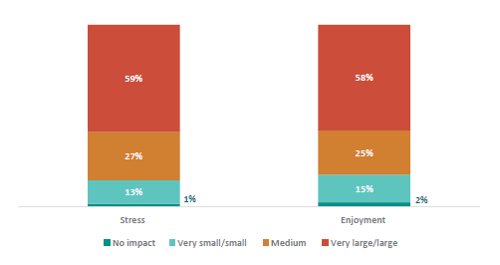

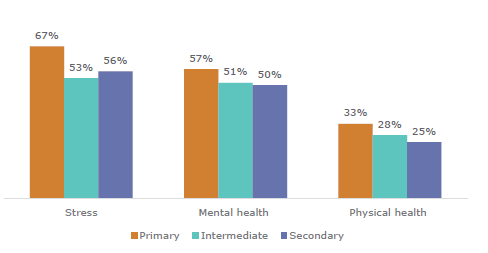

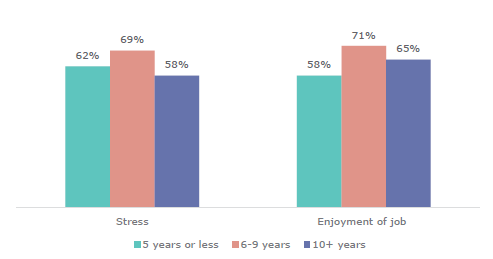

- Behaviour impacts on teacher wellbeing through mental health, physical health, and stress.

- Half of teachers (50 percent) say this has a large impact on their intention to stay in the profession.

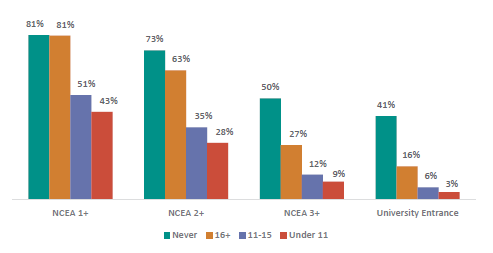

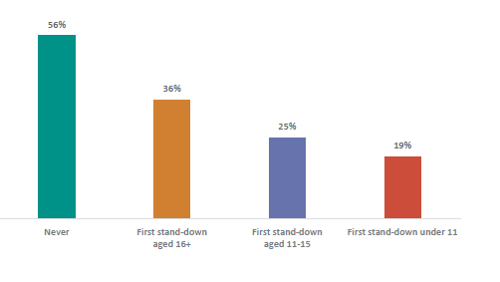

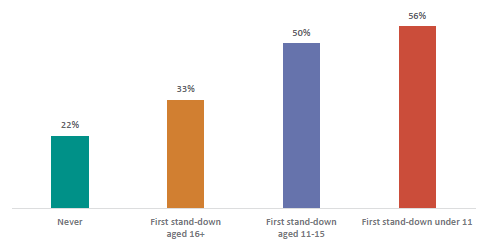

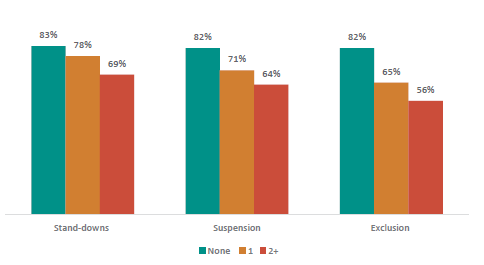

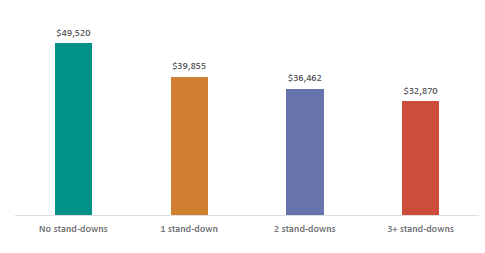

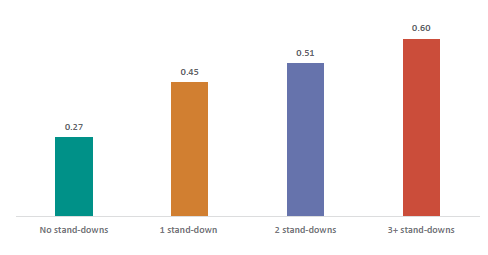

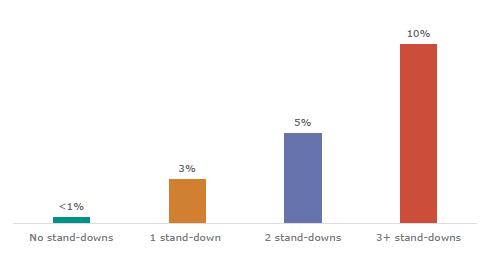

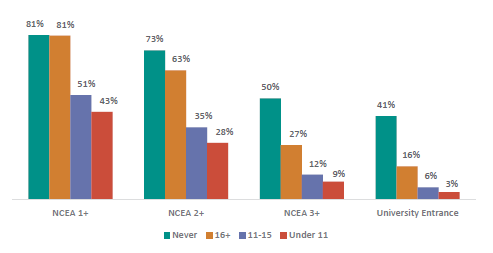

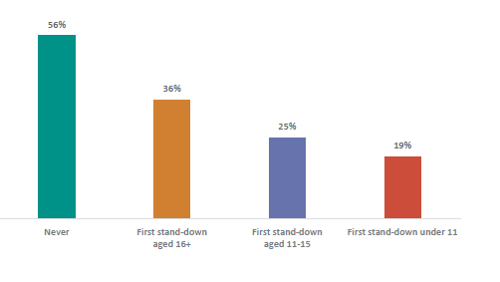

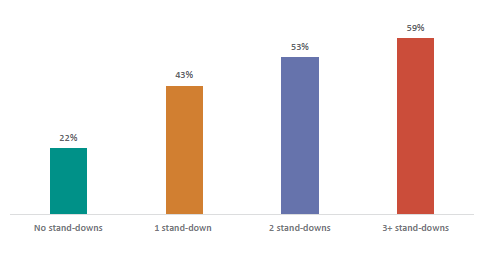

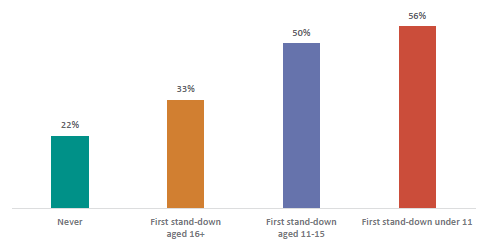

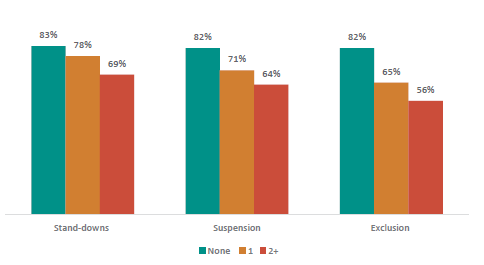

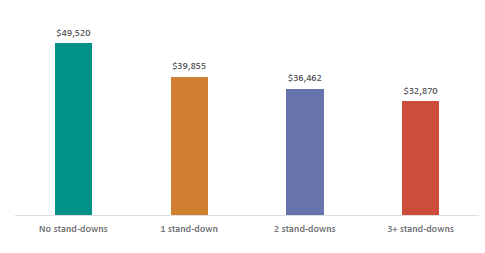

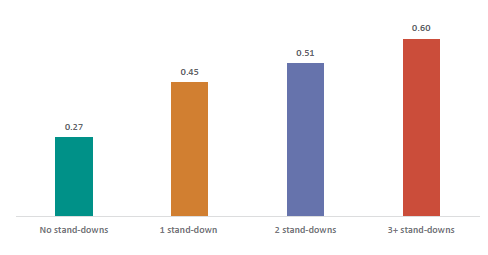

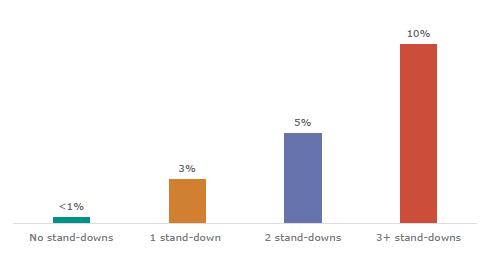

6. Behaviour is associated with negative life outcomes.

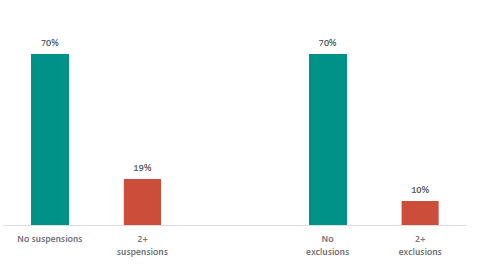

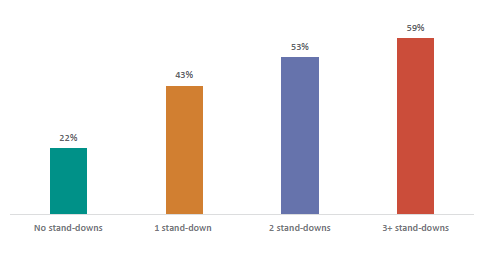

- Student behaviour is sometimes managed through being stood-down (not allowed to attend school). These students have worse life outcomes.

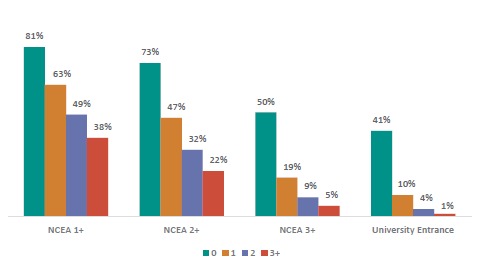

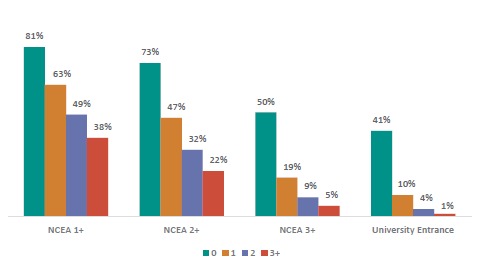

- Students with three or more stand-downs are less than a third as likely to leave school with NCEA Level 2 (22 percent) than those with no stand-downs (73 percent).

- Experiencing stand-downs is linked to other longer-term outcomes such as unemployment, offending, and poor health.

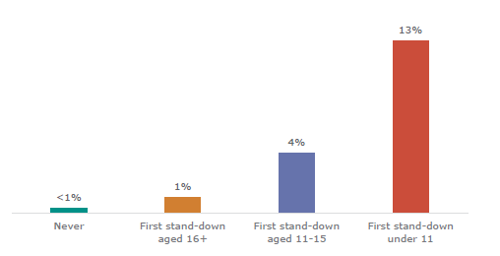

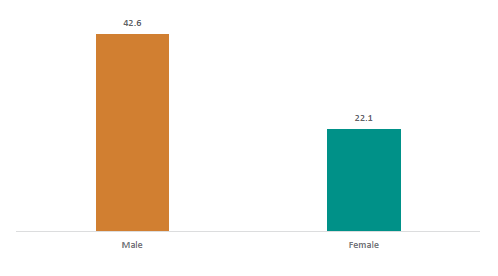

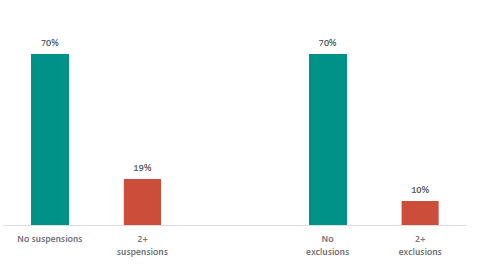

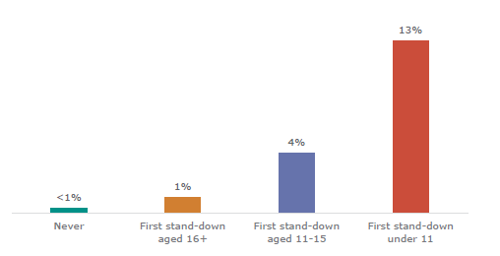

- The younger a student’s first stand-down, suspension, or exclusion, the more likely they are to receive a benefit, have lower income, have a greater number of admissions to emergency departments, offend, or receive a custodial sentence.

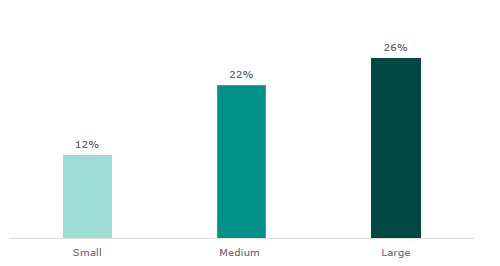

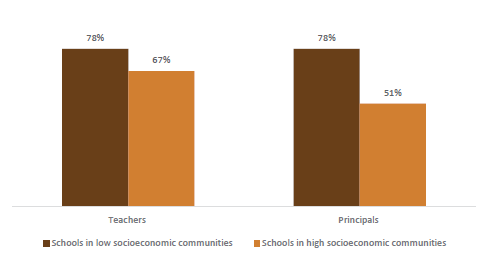

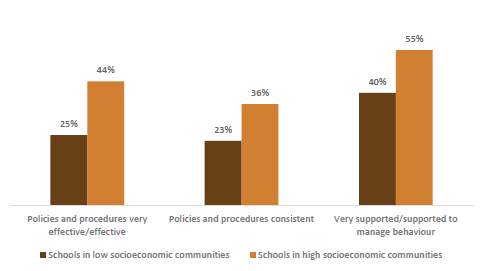

7. Behaviour issues are particularly severe in large schools and schools in low socioeconomic communities.

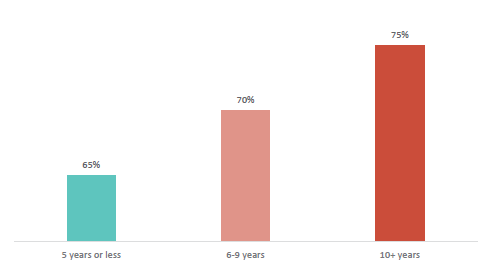

- Teachers at larger schools see challenging behaviour more often, such as refusal to follow instructions (75 percent of teachers at large schools see this every day, compared with 65 percent of teachers at small schools).

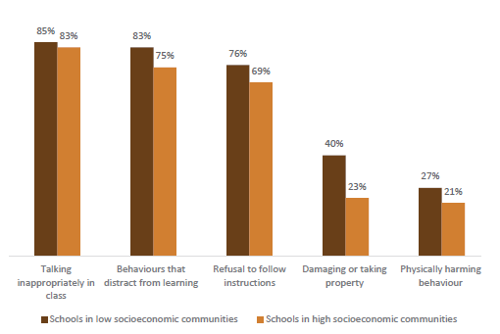

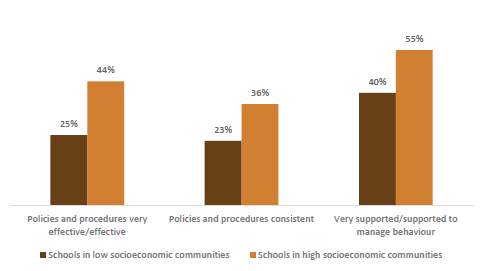

- Teachers from schools in low socioeconomic communities also see challenging behaviour more often, such as damaging or taking property (40 percent see this at least every day, compared to 23 percent from schools in high socioeconomic communities), reflecting the additional challenges in these communities.

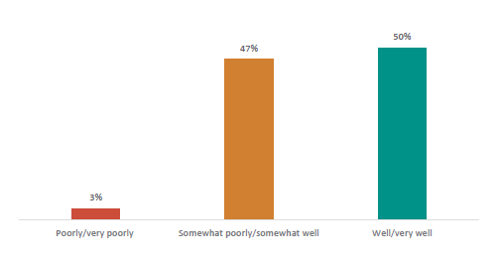

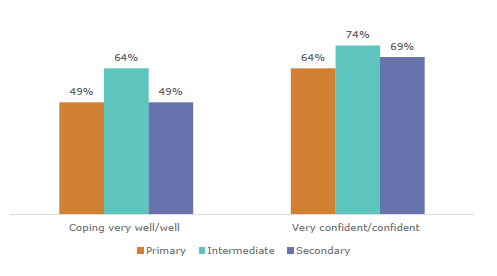

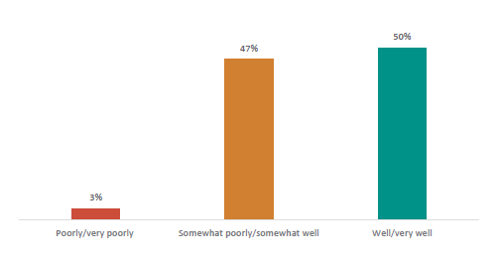

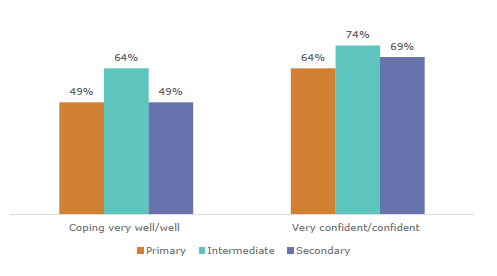

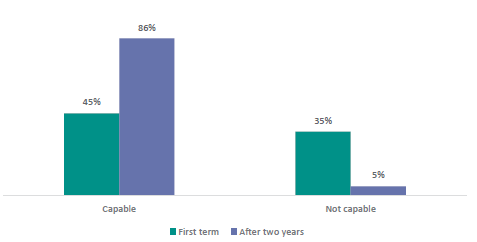

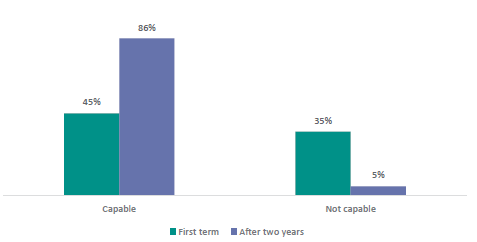

8. Teachers are not all well prepared to manage behaviour.

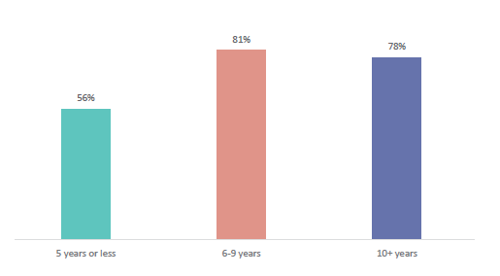

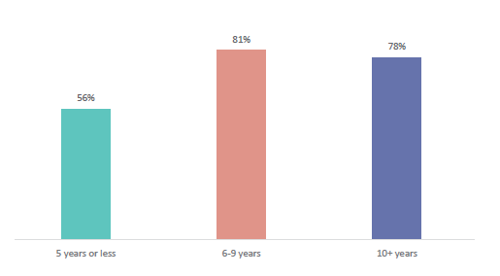

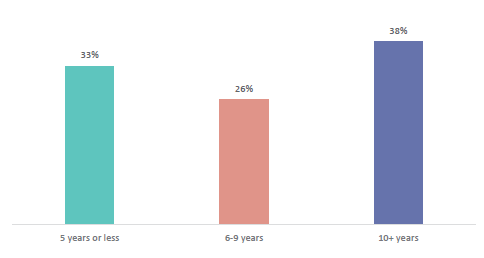

- Less than half (45 percent) of new teachers report being capable of managing behaviours in the classroom in their first term.

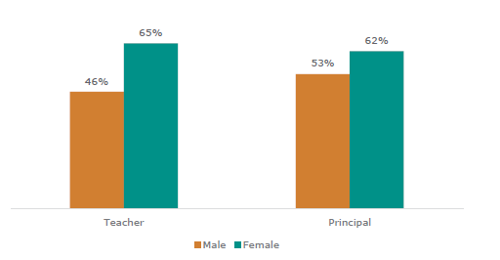

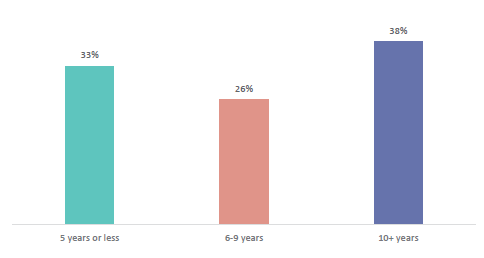

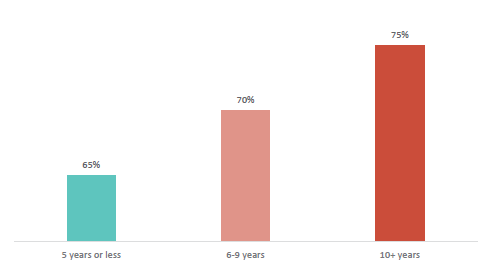

- Older new teachers (aged 36 and above) are more prepared to manage behaviour in their first term teaching than teachers aged 35 or younger.

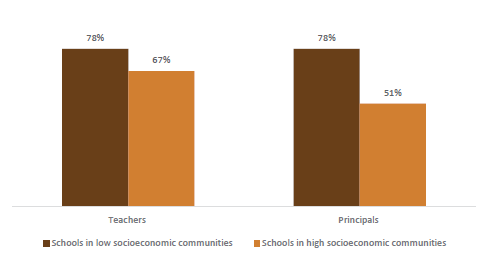

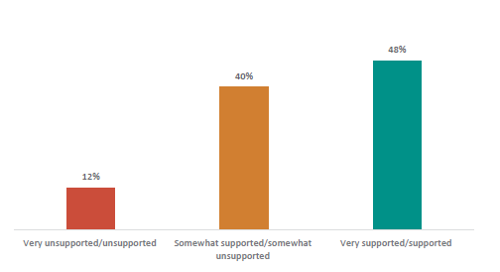

9. Many teachers and principals struggle to access the expert support they need, particularly in secondary schools and schools in low socioeconomic communities.

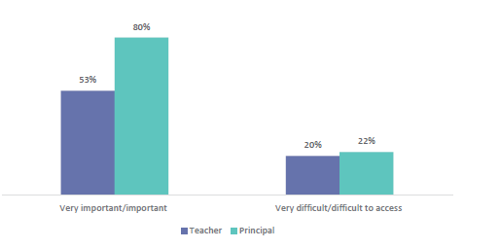

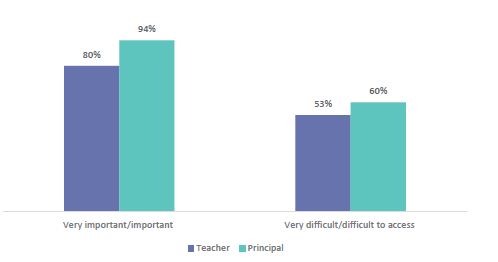

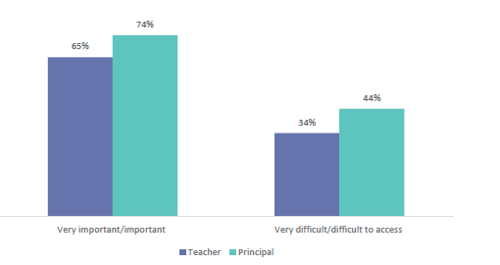

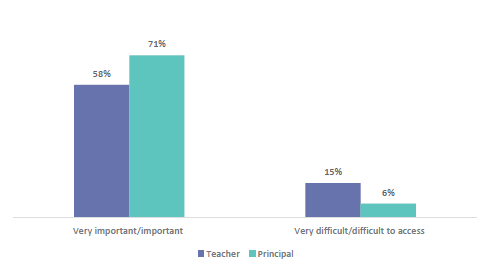

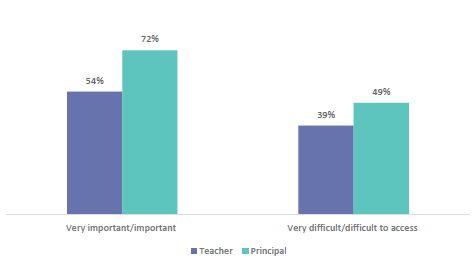

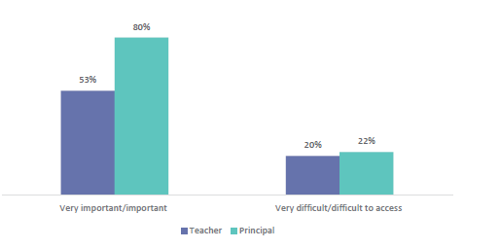

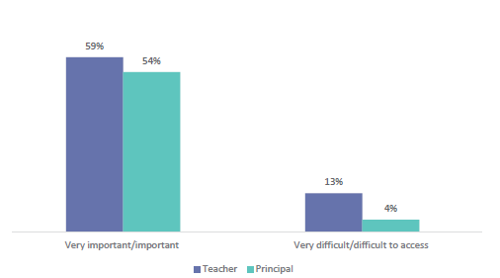

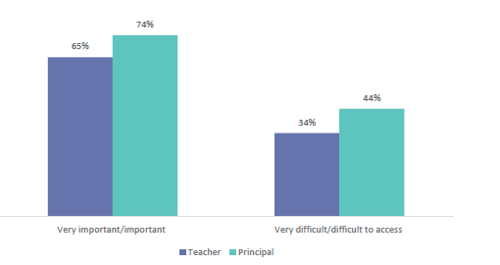

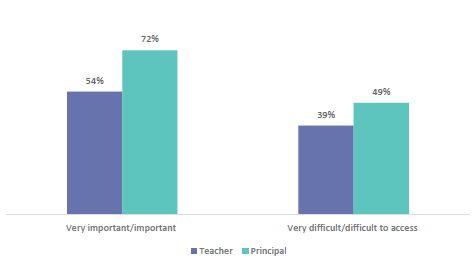

- Half of teachers (54 percent) and three-quarters of principals (72 percent) find timely advice from experts to be an important support, yet four in 10 (39 percent) teachers and half of principals (49 percent) find it difficult to access.

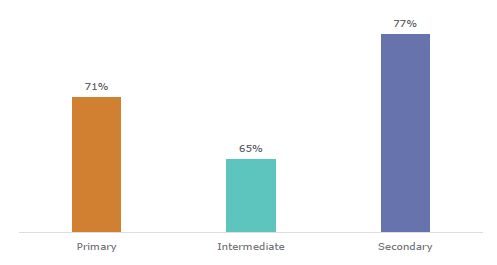

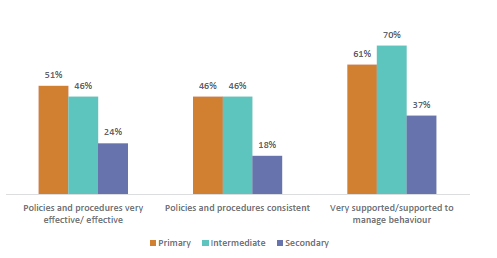

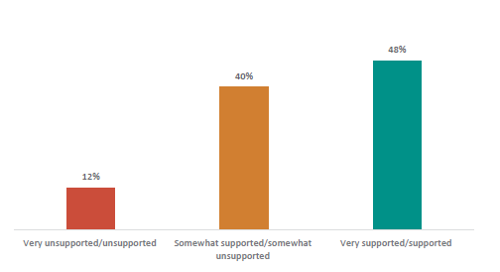

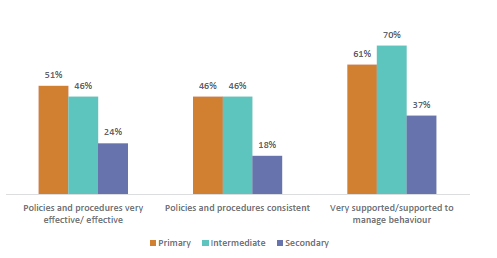

- Teachers at secondary school feel the least supported, and that their behavioural policies and procedures are the least effective and applied the least consistently.

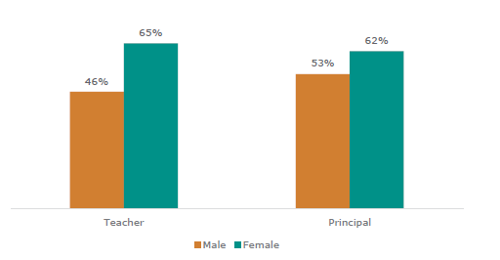

10. Teachers struggle to find the time to respond to behaviour.

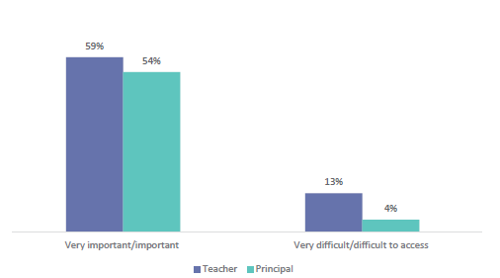

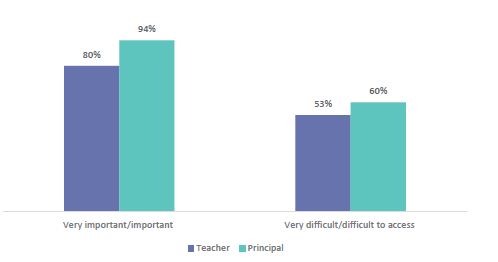

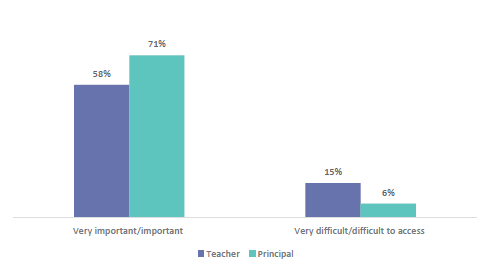

- Over half of teachers (53 percent) and principals (60 percent) find it difficult to access the time they need to tackle behaviour issues.

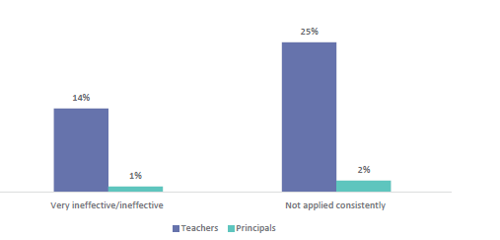

11. There are inconsistencies in behaviour management within schools and between schools.

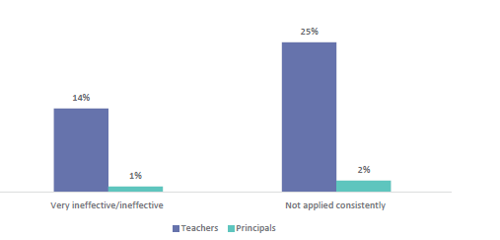

- One in four teachers (25 percent) report that their school’s behaviour policies and procedures are not applied consistently at their school. But just 2 percent of principals think they are not applied consistently.

Evidence-based practice

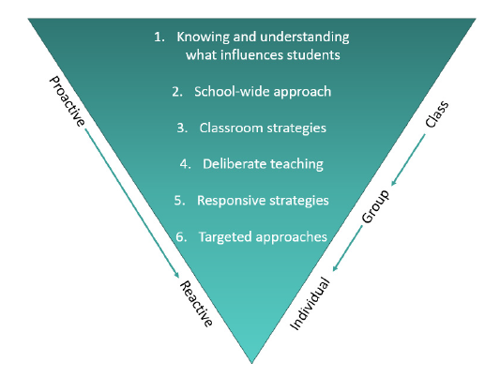

Effective behaviour management uses a combination of ‘proactive’ and ‘reactive’ strategies.

We reviewed international and local evidence to find the most effective practices for managing challenging behaviour in schools. These evidence-based strategies are a combination of ‘proactive’ (preventing challenging behaviour) and ‘reactive’ (responding to challenging behaviour) approaches.

Table 1: Evidence-based practice areas

|

Proactive |

Practice area 1 |

Know and understand students and what influences their behaviour This involves teachers sourcing information about the range of factors that influence student behaviour. These include past behaviours and incidents, attendance and achievement information, individual needs, and family or wider community contexts. Knowing about these influences equips teachers to understand classroom behaviours and choose effective strategies. |

|

|

Practice area 2 |

Use a consistent approach across the school to prevent and manage challenging behaviour A whole-school approach to behaviour management means all staff and students have shared understandings and clear expectations around behaviour. A whole-school approach includes training on how to implement agreed behaviour management strategies, and careful monitoring across the school through systematically tracking behaviour data. |

|

|

|

Practice area 3 |

Use strategies in the classroom to support expected behaviour Classroom strategies for managing behaviour start with setting high behavioural expectations and clear, logical consequences for challenging behaviour. These are developed and implemented with students, documented, discussed often, and consistently applied. The classroom layout (e.g. seating arrangements, visual displays) aligns with these expectations. |

||

|

Practice area 4 |

Teach learning behaviours alongside managing challenging behaviour This involves explicitly teaching students positive classroom behaviours like listening to instructions, working well with classmates, monitoring their own behaviour, and persisting with classroom tasks. Setting students up with positive learning behaviours reduces the need to manage challenging behaviour. |

||

|

Reactive |

|||

|

Practice area 5 |

Respond effectively to challenging behaviour This involves teachers being confident in a range of effective responses to challenging behaviour. Strategies include clear and immediate feedback to correct minor challenging behaviours like talking at inappropriate times, as well as logical consequences for more serious or recurring behaviours. |

||

|

Practice area 6 |

Use targeted approaches to meet the individual needs of students Targeted approaches are intended for students with the most challenging behaviour. Leaders and teachers work with experts and parents and whānau to plan and implement specific strategies for individual students, that align with the whole-school behaviour management approach. |

Recommendations

ERO has 16 recommendations, set out below.

Cross-cutting: Moving to a national approach.

Recommendation 1: Prioritise classroom behaviour and move to a more national approach to support all schools to prevent, notice, and respond to challenging behaviours effectively. This needs to include a more consistent set of expert supports and programmes for schools, based off a stronger evidence base of what is effective.

Area 1: Increase accountability and set clear expectations

Recommendation 2: ERO to include a sharper focus in its reviews of schools on schools’ behavioural climate, policies, and plans for managing behaviour.

Recommendation 3: Provide national guidance to school boards on clear minimum expectations of the behaviour climate, and for boards to set clear expectations for behaviour across their schools and ensure that these are understood by teachers and parents and whānau.

Area 2: Greater prevention

Recommendation 4: Increase in-school and out-of-school support that identifies and addresses underlying causes of behaviour, e.g. intensive parenting support, access to counselling to reduce anxiety, and support to develop individualised behaviour plans.

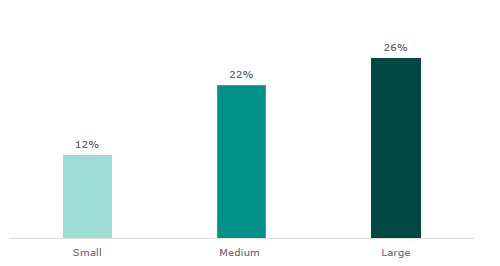

Recommendation 5: Examine school size and structures within larger schools – noting that behaviour in large schools is more of a problem than in smaller schools.

Recommendation 6: Support schools to monitor behaviour, identify issues early, and ensure information on prior behaviour is passed between settings (e.g. early learning to schools, primary to secondary).

Recommendation 7: Support schools to adopt evidence-based practices that promote positive behaviour and increase consistency of how behaviour is managed within the school.

Area 3: Raising teachers’ capability

Recommendation 8: Increase the focus on managing behaviour as part of Initial Teacher Education (building on the practice of the Initial Teacher Education providers who do this well) and within the first two years of induction of beginning teachers, and within the Teaching Standards (Teaching Council).

Recommendation 9: Increase recruitment of more mature Initial Teacher Education students who are better able to manage behaviour.

Recommendation 10: Prioritise evidence-based professional learning and development for teachers on effective approaches to managing behaviour and consider nationally accredited professional learning and development.

Area 4: Greater investment in effective support

Recommendation 11: Increase availability of specialist support for students (e.g. educational psychologists, this will require increasing supply).

Recommendation 12: Identify and grow the most effective (and value for money) supports and programmes and embed these consistently in all schools, including evaluating the effectiveness of current programmes (such as Positive Behaviour for learning).

Recommendation 13: Review the learning support workforce and funding models to ensure schools and teachers can access the right supports at the right time.

Recommendation 14: Prioritise support for schools with the largest behavioural issues, including larger schools and schools in low socioeconomic communities.

Area 5: Effective consequences

Recommendation 15: Provide clear guidance to schools on what the most effective consequences for challenging behaviour are and how to use them to achieve the best outcomes for students.

Recommendation 16: Ensure suspensions remain a last resort and that they trigger individual behaviour plans and the support needed for successful changes of behaviour.

Good classroom behaviour is critical for creating learning environments in which students can learn and achieve, and teachers can be most effective. But ensuring positive behaviour isn’t just up to schools – it requires shared responsibility and deliberate, joint actions.

This report describes the challenging behaviours teachers face in schools, the impact of those behaviours, and recommendations for action. Our companion good practice report also shares examples of how teachers and schools can effectively manage behaviour.

Behaviour in schools impacts on learning

Classroom behaviour impacts the learning of all students. Maintaining good behaviour in school classrooms is crucial for creating an environment where students can learn and achieve. In classes with positive behaviour, teachers are able to better use their time teaching, and less time reacting to and managing behaviours. This places far less strain on their health and enjoyment of the job, allowing them to teach at their best. For students, better behaviour in classrooms means less disruptions, allowing them to focus on learning.

ERO has looked at the behaviour in classrooms in Aotearoa New Zealand and how this is changing

This evaluation report sets out what ERO has found about behaviour in classrooms and the impact of behaviour on students and teachers. The companion good practice report shares practical strategies for teachers and leaders to support improvements in managing challenging behaviour in their schools.

Key findings

1. Behaviour is a major problem in Aotearoa New Zealand schools, and it is worse than other countries.

- Half of teachers have to deal with students calling out and distracting others in every lesson.

- A quarter of principals see students physically harming others and damaging or taking property every day.

- PISA results over the last 20 years show that Aotearoa New Zealand’s classrooms have consistently had worse behaviour compared to most other OECD countries. For example, Aotearoa New Zealand is lowest among OECD for behaviour in maths classes and in the bottom quarter of PISA countries for behaviour in English classes.

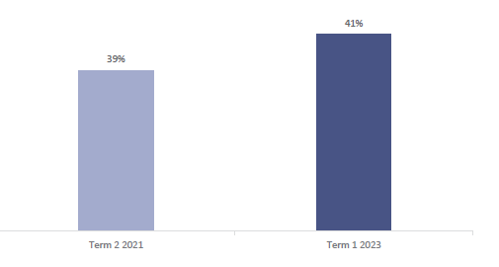

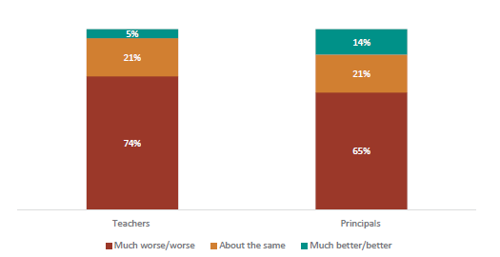

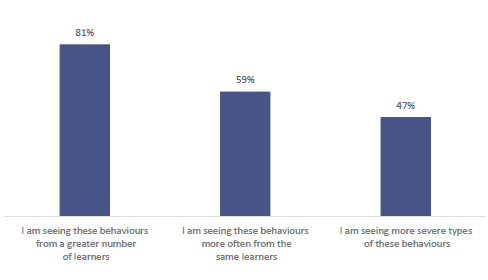

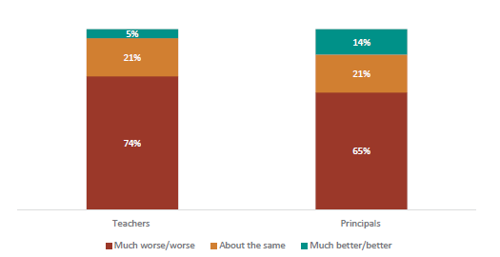

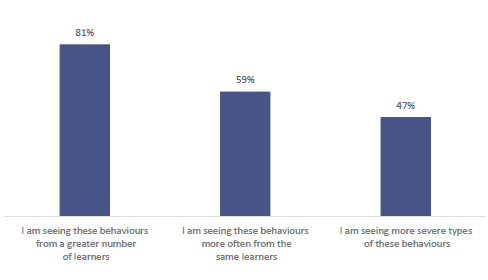

2. Student behaviour has become worse in the last two years.

- Over half of teachers report all types of behaviour have become worse. In particular, they report a greater number of students displaying challenging behaviour.

3. Behaviour is significantly damaging student learning and achievement.

- Almost half (47 percent) of teachers spend 40-50 mins a day or more responding to challenging behaviour. This limits the time available to teach.

- Three-quarters of teachers believe student behaviour is impacting on students’ progress.

- International evidence (PISA) links behaviour and achievement, finding students in the most well-behaved maths classes scored significantly higher than all other students, and students in the worst-behaved classes scored the lowest.

4. Behaviour is significantly impacting student enjoyment of school and therefore attendance.

- Two-thirds of teachers (68 percent) and principals (63 percent) find that challenging behaviour in the classroom has a large impact on student enjoyment. Enjoyment of school is a key driver of attendance.

5. Behaviour is a key driver of teachers leaving teaching.

- Behaviour impacts on teacher wellbeing through mental health, physical health, and stress.

- Half of teachers (50 percent) say this has a large impact on their intention to stay in the profession.

6. Behaviour is associated with negative life outcomes.

- Student behaviour is sometimes managed through being stood-down (not allowed to attend school). These students have worse life outcomes.

- Students with three or more stand-downs are less than a third as likely to leave school with NCEA Level 2 (22 percent) than those with no stand-downs (73 percent).

- Experiencing stand-downs is linked to other longer-term outcomes such as unemployment, offending, and poor health.

- The younger a student’s first stand-down, suspension, or exclusion, the more likely they are to receive a benefit, have lower income, have a greater number of admissions to emergency departments, offend, or receive a custodial sentence.

7. Behaviour issues are particularly severe in large schools and schools in low socioeconomic communities.

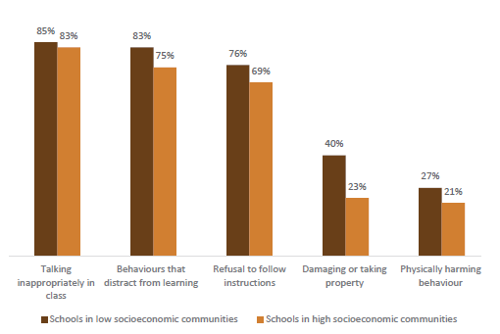

- Teachers at larger schools see challenging behaviour more often, such as refusal to follow instructions (75 percent of teachers at large schools see this every day, compared with 65 percent of teachers at small schools).

- Teachers from schools in low socioeconomic communities also see challenging behaviour more often, such as damaging or taking property (40 percent see this at least every day, compared to 23 percent from schools in high socioeconomic communities), reflecting the additional challenges in these communities.

8. Teachers are not all well prepared to manage behaviour.

- Less than half (45 percent) of new teachers report being capable of managing behaviours in the classroom in their first term.

- Older new teachers (aged 36 and above) are more prepared to manage behaviour in their first term teaching than teachers aged 35 or younger.

9. Many teachers and principals struggle to access the expert support they need, particularly in secondary schools and schools in low socioeconomic communities.

- Half of teachers (54 percent) and three-quarters of principals (72 percent) find timely advice from experts to be an important support, yet four in 10 (39 percent) teachers and half of principals (49 percent) find it difficult to access.

- Teachers at secondary school feel the least supported, and that their behavioural policies and procedures are the least effective and applied the least consistently.

10. Teachers struggle to find the time to respond to behaviour.

- Over half of teachers (53 percent) and principals (60 percent) find it difficult to access the time they need to tackle behaviour issues.

11. There are inconsistencies in behaviour management within schools and between schools.

- One in four teachers (25 percent) report that their school’s behaviour policies and procedures are not applied consistently at their school. But just 2 percent of principals think they are not applied consistently.

Evidence-based practice

Effective behaviour management uses a combination of ‘proactive’ and ‘reactive’ strategies.

We reviewed international and local evidence to find the most effective practices for managing challenging behaviour in schools. These evidence-based strategies are a combination of ‘proactive’ (preventing challenging behaviour) and ‘reactive’ (responding to challenging behaviour) approaches.

Table 1: Evidence-based practice areas

|

Proactive |

Practice area 1 |

Know and understand students and what influences their behaviour This involves teachers sourcing information about the range of factors that influence student behaviour. These include past behaviours and incidents, attendance and achievement information, individual needs, and family or wider community contexts. Knowing about these influences equips teachers to understand classroom behaviours and choose effective strategies. |

|

|

Practice area 2 |

Use a consistent approach across the school to prevent and manage challenging behaviour A whole-school approach to behaviour management means all staff and students have shared understandings and clear expectations around behaviour. A whole-school approach includes training on how to implement agreed behaviour management strategies, and careful monitoring across the school through systematically tracking behaviour data. |

|

|

|

Practice area 3 |

Use strategies in the classroom to support expected behaviour Classroom strategies for managing behaviour start with setting high behavioural expectations and clear, logical consequences for challenging behaviour. These are developed and implemented with students, documented, discussed often, and consistently applied. The classroom layout (e.g. seating arrangements, visual displays) aligns with these expectations. |

||

|

Practice area 4 |

Teach learning behaviours alongside managing challenging behaviour This involves explicitly teaching students positive classroom behaviours like listening to instructions, working well with classmates, monitoring their own behaviour, and persisting with classroom tasks. Setting students up with positive learning behaviours reduces the need to manage challenging behaviour. |

||

|

Reactive |

|||

|

Practice area 5 |

Respond effectively to challenging behaviour This involves teachers being confident in a range of effective responses to challenging behaviour. Strategies include clear and immediate feedback to correct minor challenging behaviours like talking at inappropriate times, as well as logical consequences for more serious or recurring behaviours. |

||

|

Practice area 6 |

Use targeted approaches to meet the individual needs of students Targeted approaches are intended for students with the most challenging behaviour. Leaders and teachers work with experts and parents and whānau to plan and implement specific strategies for individual students, that align with the whole-school behaviour management approach. |

Recommendations

ERO has 16 recommendations, set out below.

Cross-cutting: Moving to a national approach.

Recommendation 1: Prioritise classroom behaviour and move to a more national approach to support all schools to prevent, notice, and respond to challenging behaviours effectively. This needs to include a more consistent set of expert supports and programmes for schools, based off a stronger evidence base of what is effective.

Area 1: Increase accountability and set clear expectations

Recommendation 2: ERO to include a sharper focus in its reviews of schools on schools’ behavioural climate, policies, and plans for managing behaviour.

Recommendation 3: Provide national guidance to school boards on clear minimum expectations of the behaviour climate, and for boards to set clear expectations for behaviour across their schools and ensure that these are understood by teachers and parents and whānau.

Area 2: Greater prevention

Recommendation 4: Increase in-school and out-of-school support that identifies and addresses underlying causes of behaviour, e.g. intensive parenting support, access to counselling to reduce anxiety, and support to develop individualised behaviour plans.

Recommendation 5: Examine school size and structures within larger schools – noting that behaviour in large schools is more of a problem than in smaller schools.

Recommendation 6: Support schools to monitor behaviour, identify issues early, and ensure information on prior behaviour is passed between settings (e.g. early learning to schools, primary to secondary).

Recommendation 7: Support schools to adopt evidence-based practices that promote positive behaviour and increase consistency of how behaviour is managed within the school.

Area 3: Raising teachers’ capability

Recommendation 8: Increase the focus on managing behaviour as part of Initial Teacher Education (building on the practice of the Initial Teacher Education providers who do this well) and within the first two years of induction of beginning teachers, and within the Teaching Standards (Teaching Council).

Recommendation 9: Increase recruitment of more mature Initial Teacher Education students who are better able to manage behaviour.

Recommendation 10: Prioritise evidence-based professional learning and development for teachers on effective approaches to managing behaviour and consider nationally accredited professional learning and development.

Area 4: Greater investment in effective support

Recommendation 11: Increase availability of specialist support for students (e.g. educational psychologists, this will require increasing supply).

Recommendation 12: Identify and grow the most effective (and value for money) supports and programmes and embed these consistently in all schools, including evaluating the effectiveness of current programmes (such as Positive Behaviour for learning).

Recommendation 13: Review the learning support workforce and funding models to ensure schools and teachers can access the right supports at the right time.

Recommendation 14: Prioritise support for schools with the largest behavioural issues, including larger schools and schools in low socioeconomic communities.

Area 5: Effective consequences

Recommendation 15: Provide clear guidance to schools on what the most effective consequences for challenging behaviour are and how to use them to achieve the best outcomes for students.

Recommendation 16: Ensure suspensions remain a last resort and that they trigger individual behaviour plans and the support needed for successful changes of behaviour.

About this report

Teachers in New Zealand schools face significant behaviour challenges, and this has impacts on students. Challenging behaviour in classrooms is linked to lower engagement, achievement, and enjoyment of learning. It also has large impacts on teachers and school staff. Strong school policies and procedures, skilled teachers, and external support are required to address these challenges.

This report describes the behaviour teachers face in schools and the impact of these behaviours, across school staff and students. It is part of a set of two reports – our companion good practice report sets out practices and examples of how teachers and schools can effectively manage behaviour.

The Education Review Office (ERO) is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early learning services, kura, and schools. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports schools to provide quality education for students. In this case, we looked at how classroom behaviour going is currently, and what good practice for behaviour management looks like.

To help us know what good looks like, and know what matters for managing behaviour, we worked closely with an Expert Advisory Group with a range of expertise. The group included academics, educators, practitioners, and sector experts.

This report describes what we found about the current state of behaviour in New Zealand classrooms. To do this, we drew on the experiences of school staff, students, parents and whānau, and key experts. We describe the type, frequency, and severity of classroom behaviour, how this has changed over time, and the impacts on students, school staff, and parents and whānau. We provide examples of good practice in behaviour management, and responses that we heard are working well in classrooms across the country. We also suggest areas for improvement so schools and staff can better manage behaviour in schools, ensuring enhanced learning outcomes for all students.

What we looked at

We wanted to understand the behaviours schools are facing, as well as give them clear guidance in how best to manage these behaviours to better support focused learning.

This evaluation report looks at the current state of behaviour in schools. Our companion good practice report sets out what good practice looks like for managing classroom behaviours. Across this work, we answered five key questions.

- What are the challenging behaviours teachers face in the classroom?

- How has this changed over time?

- What is the impact of these behaviours on:

- teachers and principals?

- students and parents and whānau?

- What are the long-term impacts on students of existing responses? (i.e., stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions)?

- What does the evidence show are the effective practices?

- How does this look at different stages of the school system?

- What does this look like in practice in NZ schools?

- What needs to be in place to enable good practice?

- How are schools and teachers supported to manage challenging behaviour and what would make a difference?

What about bullying?

Bullying is a very specific form of behaviour (it is deliberate, harmful, involves a power imbalance, and has an element of repetition), which is not the focus of this evaluation. For dedicated resources on bullying in Aotearoa New Zealand schools, including a student voice resource, see ERO’s 2019 research: Bullying Prevention and Response in New Zealand Schools May 2019 | Education Review Office (ero.govt.nz)

Where we looked

We focused our investigation on experiences of schools, teachers, students and parents and whānau across Aotearoa New Zealand in English-medium state and state-integrated primary, intermediate, and secondary schools (we did not include specialist schools).

How we found out about the current state of behaviour in classrooms and what effective practice looks like

We have taken a robust, mixed-methods approach to deliver breadth and depth in this evaluation. We built our understanding of the current state of behaviour and what is good practice through:

- surveys of 1557 teachers

- surveys of 547 principals

- focus groups with:

- school staff

- students

- parents and whānau participants

- Resource Teachers: Learning and Behaviour (RTLBs) from two clusters

- site visits and online sessions with 10 schools

- an in-depth review of literature, including Education Endowment Foundation research(2)

- Ministry of Education statistics on the frequency of stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions, and expulsions.

Analysing data in the Integrated Data Infrastructure

The Social Wellbeing Agency use the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) to describe the future outcomes of people who experienced stand-downs, suspensions, and exclusions. We draw on their data and analysis in this report, and worked with them to understand the outcomes associated with these measures.

More details about our methodology are in Appendix 1.

Report structure

This report is divided into eight chapters.

- Chapter 1 sets out the context of how behaviour management works in Aotearoa New Zealand schools.

- Chapter 2 describes the challenging behaviours in classrooms.

- Chapter 3 describes how classroom behaviour is changing.

- Chapter 4 describes the impact of classroom behaviours on students, teachers, and principals.

- Chapter 5 describes longer term outcomes for students who have very challenging behaviours.

- Chapter 6 describes the challenges for teachers managing classroom behaviours.

- Chapter 7 sets out good practice in managing classroom behaviours. (More detail can be found in our companion good practice report.)

- Chapter 8 shares our key findings and areas for action.

|

We appreciate the work of all those who supported this research, particularly the teachers, school leaders, students, parents and whānau, and experts who shared with us. Their experiences and insights are at the heart of what we have learnt. |

Teachers in New Zealand schools face significant behaviour challenges, and this has impacts on students. Challenging behaviour in classrooms is linked to lower engagement, achievement, and enjoyment of learning. It also has large impacts on teachers and school staff. Strong school policies and procedures, skilled teachers, and external support are required to address these challenges.

This report describes the behaviour teachers face in schools and the impact of these behaviours, across school staff and students. It is part of a set of two reports – our companion good practice report sets out practices and examples of how teachers and schools can effectively manage behaviour.

The Education Review Office (ERO) is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early learning services, kura, and schools. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports schools to provide quality education for students. In this case, we looked at how classroom behaviour going is currently, and what good practice for behaviour management looks like.

To help us know what good looks like, and know what matters for managing behaviour, we worked closely with an Expert Advisory Group with a range of expertise. The group included academics, educators, practitioners, and sector experts.

This report describes what we found about the current state of behaviour in New Zealand classrooms. To do this, we drew on the experiences of school staff, students, parents and whānau, and key experts. We describe the type, frequency, and severity of classroom behaviour, how this has changed over time, and the impacts on students, school staff, and parents and whānau. We provide examples of good practice in behaviour management, and responses that we heard are working well in classrooms across the country. We also suggest areas for improvement so schools and staff can better manage behaviour in schools, ensuring enhanced learning outcomes for all students.

What we looked at

We wanted to understand the behaviours schools are facing, as well as give them clear guidance in how best to manage these behaviours to better support focused learning.

This evaluation report looks at the current state of behaviour in schools. Our companion good practice report sets out what good practice looks like for managing classroom behaviours. Across this work, we answered five key questions.

- What are the challenging behaviours teachers face in the classroom?

- How has this changed over time?

- What is the impact of these behaviours on:

- teachers and principals?

- students and parents and whānau?

- What are the long-term impacts on students of existing responses? (i.e., stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions)?

- What does the evidence show are the effective practices?

- How does this look at different stages of the school system?

- What does this look like in practice in NZ schools?

- What needs to be in place to enable good practice?

- How are schools and teachers supported to manage challenging behaviour and what would make a difference?

What about bullying?

Bullying is a very specific form of behaviour (it is deliberate, harmful, involves a power imbalance, and has an element of repetition), which is not the focus of this evaluation. For dedicated resources on bullying in Aotearoa New Zealand schools, including a student voice resource, see ERO’s 2019 research: Bullying Prevention and Response in New Zealand Schools May 2019 | Education Review Office (ero.govt.nz)

Where we looked

We focused our investigation on experiences of schools, teachers, students and parents and whānau across Aotearoa New Zealand in English-medium state and state-integrated primary, intermediate, and secondary schools (we did not include specialist schools).

How we found out about the current state of behaviour in classrooms and what effective practice looks like

We have taken a robust, mixed-methods approach to deliver breadth and depth in this evaluation. We built our understanding of the current state of behaviour and what is good practice through:

- surveys of 1557 teachers

- surveys of 547 principals

- focus groups with:

- school staff

- students

- parents and whānau participants

- Resource Teachers: Learning and Behaviour (RTLBs) from two clusters

- site visits and online sessions with 10 schools

- an in-depth review of literature, including Education Endowment Foundation research(2)

- Ministry of Education statistics on the frequency of stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions, and expulsions.

Analysing data in the Integrated Data Infrastructure

The Social Wellbeing Agency use the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) to describe the future outcomes of people who experienced stand-downs, suspensions, and exclusions. We draw on their data and analysis in this report, and worked with them to understand the outcomes associated with these measures.

More details about our methodology are in Appendix 1.

Report structure

This report is divided into eight chapters.

- Chapter 1 sets out the context of how behaviour management works in Aotearoa New Zealand schools.

- Chapter 2 describes the challenging behaviours in classrooms.

- Chapter 3 describes how classroom behaviour is changing.

- Chapter 4 describes the impact of classroom behaviours on students, teachers, and principals.

- Chapter 5 describes longer term outcomes for students who have very challenging behaviours.

- Chapter 6 describes the challenges for teachers managing classroom behaviours.

- Chapter 7 sets out good practice in managing classroom behaviours. (More detail can be found in our companion good practice report.)

- Chapter 8 shares our key findings and areas for action.

|

We appreciate the work of all those who supported this research, particularly the teachers, school leaders, students, parents and whānau, and experts who shared with us. Their experiences and insights are at the heart of what we have learnt. |

Chapter 1: Context

Good classroom behaviour is a critical factor for creating learning environments in which students can learn and achieve, and where teachers can be most effective. But positive behaviour isn’t just up to the students or even their schools – it requires shared responsibility and joint actions. Managing classroom behaviour involves the whole education system and support structure, as well as the school community, school leadership, staff, and parents and whānau.

There are a range of measures that teachers can take in preventing and managing challenging behaviour in the classroom. These go alongside a range of interventions available to school staff to assist with behaviour management.

This chapter sets out:

- why it is important to have good behaviour in classrooms

- how teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand deal with classroom behaviours

- what stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions, and expulsions are, and when schools use them.

1) Why is good behaviour in classrooms important?

Maintaining good behaviour in school classrooms is crucial for creating a positive and engaging learning environment where students can learn and achieve.(1) When this happens teachers are able to better use their time teaching, and less time reacting to and managing behaviours. As a result, students progress and enjoy their learning more.(2) For teachers, positive classroom behaviour climates place far less strain on their own health and enjoyment of the job, allowing them to teach at their best.(3) For schools, better behaviour in classrooms means less disruptions, allowing staff and students to focus on learning outcomes and foster a greater sense of community and positive school culture.(4)

What influences behaviour?

There is a wide range of research and evidence available about the influences on student behaviour, which can overlap and interact. Behaviour influences include, among other things:

- individual factors like temperament, developmental stage, emotional regulation skills, communication skills, and disability

- family factors such as home environment, family dynamics and parenting, family stress, and mental health of family members

- peer relationships and social dynamics

- trauma and adverse events

- community factors, like safety and availability of support services

- cultural factors, including norms around behaviour and ways to respond to behaviour, and discrimination.

In this evaluation report, our main focus is on how challenging behaviours present within the classroom – rather than the ‘causes’ of those behaviours.

The companion good practice report talks about the importance of knowing and understanding students’ contexts as one of the elements of effective behaviour management.

2) How teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand approach classroom behaviours

Managing behaviour in Aotearoa New Zealand schools begins with school leadership (in collaboration with the school community) setting the culture, values, and behavioural expectations for a school and its students. In many schools this is communicated through documents that describe the expectations, procedures, and methods for implementation. Many also use visual guides to remind all staff, students, parents and whānau, and the wider community of the expectations and policies. These policies are often unique to each school, reflecting the values of the community and school context, but also drawing on the national expectations and legislation set out by the Ministry of Education.

At the classroom level, teachers encourage appropriate behaviour through a range of techniques, such as setting up the classroom effectively with teachers:

- reinforcing expectations and values through explicit teaching and discussion so students are reminded of the behavioural expectations of their school

- taking consideration when designing the physical layout of the classroom, including desk or seating arrangements

- displaying behavioural expectations, values of the school, and other informational materials such as posters showing how to regulate emotions.

Teachers need to be skilled in strategies for response, de-escalation, and general behaviour management. This includes understanding influences on behaviour, and how classroom behaviour functions as a form of communication and interaction between teachers and students. The teacher plays an important role in setting students up for success. High-quality and effective preventative measures can help reduce the time teachers spend responding to behaviour.

When behaviours begin to escalate beyond what the teacher can manage in the classroom, schools explore a range of options. These responses are tailored to the specific student, and often planned by designated school staff or the principal. These responses include things like behaviour management plans, adapting systems and environments, parent and whānau meetings, or counselling.

Alongside expectations sit procedures that guide how behaviour is managed. This may be prescriptive on how each behaviour is responded to and by whom, although this varies by school. Over two-fifths of Aotearoa New Zealand schools use Positive Behaviour for Learning Schoolwide (PB4L), which is a framework for schools to design their behavioural support system and approaches to behaviour from low-level to chronic and severe challenging behaviour, allowing a clear escalation framework. It is based on the Schoolwide Positive Behaviour Support framework from the United States.(5) PB4L is just one of the behavioural initiatives employed by schools in Aotearoa New Zealand and is funded by Ministry of Education. It includes Incredible Years, Mana Tikitiki, Huakina Mai, Check and Connect, and SchoolWide (other commonly used systems can be seen in our good practice report).

3) Stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions, and expulsions

When behaviours become more serious, through consistency, severity, or level of harm, schools and leaders may decide to remove the student from the school. Stand‑downs, suspensions, and exclusions are used by schools as a last resort.(6) Principals stand down or suspend students if they believe the student’s gross misconduct or continual disobedience is a harmful or dangerous example to other students, or if it is likely that the student themselves, or other students at the school will be seriously harmed if the student remains at school. For suspensions, the school board must hold a suspension meeting within seven school days, where they decide how to proceed.(7)

Following the suspension meeting, if the suspension is lifted, the child returns to school the next day. A decision may be made that the child return to school without conditions, or with conditions designed to facilitate the return of the student to school and relate to the behaviour or cause of behaviour that led to the suspension. This may include guidance and counselling, such as drug and alcohol counselling or anger management counselling.

Exclusions (students under 16) and expulsions (students over 16) are the formal removal of students from school. The decision to exclude or expel a student is made by the school board during a student’s suspension, at a suspension meeting. The board can decide to lift the suspension (often with conditions such as a behaviour management course), extend the suspension, or exclude/expel the student. When a child under 16 is excluded, their principal has to arrange their enrolment in another school. For expulsions, the student does not need to find another school and if they wish to do so, this is left up to the parents. Students will often leave the school system upon expulsion. Exclusions and expulsions should only occur at the extreme end of behaviour when all other options have been reasonably considered.(8)

Table 2: Table summarising stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions, and expulsions

|

Intervention |

What is it? |

When/why |

How/what is the process |

Next steps |

|

Stand-down |

Student is removed from school for a short period – no more than five days in a school term or a total of 10 days in a school year. |

Can only be used for: · continual disobedience which is harmful or dangerous · gross misconduct (e.g., serious challenging behaviour which is harmful or dangerous) · potential to cause serious harm to themselves or others. |

Only a principal or acting principal can do this. Takes effect the day after the principal’s decision is made, the student may be made to leave on the same day. |

The student can return to school or kura on the date decided by the principal.

|

|

Suspension |

The formal removal of a student from school or kura by the principal, until the school board meets to decide what to do. |

The principal must determine whether a suspension is warranted on any of the grounds above. The personal circumstances of the child, and in which the incident or behaviour happened are also considered. |

Suspension meeting with the board, principal, and parents - an independent review of the principal’s decision. The principal is not involved in the decision but may attend. |

The board can decide to: - lift the suspension without conditions - lift the suspension with conditions - extend the suspension - exclude the child if under 16 - expel the child if over 16. |

|

Exclusion |

The formal removal of a student from school or kura if they are under 16 years. They must enrol in another school or kura. |

Same reasons as suspension but generally more severe. |

This is one outcome of a suspension meeting. |

The principal has 10 school days to try to arrange for the student to attend another school or kura. If they can’t do this, they must inform MoE who will then help. |

|

Expulsion |

The formal, permanent removal of a student from school or kura if they are 16 years old or older. |

Same reasons as suspension but generally more sever to result in expulsion. |

This is one outcome of a suspension meeting. |

The principal does not have to try to find another school or kura for the student but will inform MoE if the student wants to continue with their schooling. |

Good classroom behaviour is a critical factor for creating learning environments in which students can learn and achieve, and where teachers can be most effective. But positive behaviour isn’t just up to the students or even their schools – it requires shared responsibility and joint actions. Managing classroom behaviour involves the whole education system and support structure, as well as the school community, school leadership, staff, and parents and whānau.

There are a range of measures that teachers can take in preventing and managing challenging behaviour in the classroom. These go alongside a range of interventions available to school staff to assist with behaviour management.

This chapter sets out:

- why it is important to have good behaviour in classrooms

- how teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand deal with classroom behaviours

- what stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions, and expulsions are, and when schools use them.

1) Why is good behaviour in classrooms important?

Maintaining good behaviour in school classrooms is crucial for creating a positive and engaging learning environment where students can learn and achieve.(1) When this happens teachers are able to better use their time teaching, and less time reacting to and managing behaviours. As a result, students progress and enjoy their learning more.(2) For teachers, positive classroom behaviour climates place far less strain on their own health and enjoyment of the job, allowing them to teach at their best.(3) For schools, better behaviour in classrooms means less disruptions, allowing staff and students to focus on learning outcomes and foster a greater sense of community and positive school culture.(4)

What influences behaviour?

There is a wide range of research and evidence available about the influences on student behaviour, which can overlap and interact. Behaviour influences include, among other things:

- individual factors like temperament, developmental stage, emotional regulation skills, communication skills, and disability

- family factors such as home environment, family dynamics and parenting, family stress, and mental health of family members

- peer relationships and social dynamics

- trauma and adverse events

- community factors, like safety and availability of support services

- cultural factors, including norms around behaviour and ways to respond to behaviour, and discrimination.

In this evaluation report, our main focus is on how challenging behaviours present within the classroom – rather than the ‘causes’ of those behaviours.

The companion good practice report talks about the importance of knowing and understanding students’ contexts as one of the elements of effective behaviour management.

2) How teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand approach classroom behaviours

Managing behaviour in Aotearoa New Zealand schools begins with school leadership (in collaboration with the school community) setting the culture, values, and behavioural expectations for a school and its students. In many schools this is communicated through documents that describe the expectations, procedures, and methods for implementation. Many also use visual guides to remind all staff, students, parents and whānau, and the wider community of the expectations and policies. These policies are often unique to each school, reflecting the values of the community and school context, but also drawing on the national expectations and legislation set out by the Ministry of Education.

At the classroom level, teachers encourage appropriate behaviour through a range of techniques, such as setting up the classroom effectively with teachers:

- reinforcing expectations and values through explicit teaching and discussion so students are reminded of the behavioural expectations of their school

- taking consideration when designing the physical layout of the classroom, including desk or seating arrangements

- displaying behavioural expectations, values of the school, and other informational materials such as posters showing how to regulate emotions.

Teachers need to be skilled in strategies for response, de-escalation, and general behaviour management. This includes understanding influences on behaviour, and how classroom behaviour functions as a form of communication and interaction between teachers and students. The teacher plays an important role in setting students up for success. High-quality and effective preventative measures can help reduce the time teachers spend responding to behaviour.

When behaviours begin to escalate beyond what the teacher can manage in the classroom, schools explore a range of options. These responses are tailored to the specific student, and often planned by designated school staff or the principal. These responses include things like behaviour management plans, adapting systems and environments, parent and whānau meetings, or counselling.

Alongside expectations sit procedures that guide how behaviour is managed. This may be prescriptive on how each behaviour is responded to and by whom, although this varies by school. Over two-fifths of Aotearoa New Zealand schools use Positive Behaviour for Learning Schoolwide (PB4L), which is a framework for schools to design their behavioural support system and approaches to behaviour from low-level to chronic and severe challenging behaviour, allowing a clear escalation framework. It is based on the Schoolwide Positive Behaviour Support framework from the United States.(5) PB4L is just one of the behavioural initiatives employed by schools in Aotearoa New Zealand and is funded by Ministry of Education. It includes Incredible Years, Mana Tikitiki, Huakina Mai, Check and Connect, and SchoolWide (other commonly used systems can be seen in our good practice report).

3) Stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions, and expulsions

When behaviours become more serious, through consistency, severity, or level of harm, schools and leaders may decide to remove the student from the school. Stand‑downs, suspensions, and exclusions are used by schools as a last resort.(6) Principals stand down or suspend students if they believe the student’s gross misconduct or continual disobedience is a harmful or dangerous example to other students, or if it is likely that the student themselves, or other students at the school will be seriously harmed if the student remains at school. For suspensions, the school board must hold a suspension meeting within seven school days, where they decide how to proceed.(7)

Following the suspension meeting, if the suspension is lifted, the child returns to school the next day. A decision may be made that the child return to school without conditions, or with conditions designed to facilitate the return of the student to school and relate to the behaviour or cause of behaviour that led to the suspension. This may include guidance and counselling, such as drug and alcohol counselling or anger management counselling.

Exclusions (students under 16) and expulsions (students over 16) are the formal removal of students from school. The decision to exclude or expel a student is made by the school board during a student’s suspension, at a suspension meeting. The board can decide to lift the suspension (often with conditions such as a behaviour management course), extend the suspension, or exclude/expel the student. When a child under 16 is excluded, their principal has to arrange their enrolment in another school. For expulsions, the student does not need to find another school and if they wish to do so, this is left up to the parents. Students will often leave the school system upon expulsion. Exclusions and expulsions should only occur at the extreme end of behaviour when all other options have been reasonably considered.(8)

Table 2: Table summarising stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions, and expulsions

|

Intervention |

What is it? |

When/why |

How/what is the process |

Next steps |

|

Stand-down |

Student is removed from school for a short period – no more than five days in a school term or a total of 10 days in a school year. |

Can only be used for: · continual disobedience which is harmful or dangerous · gross misconduct (e.g., serious challenging behaviour which is harmful or dangerous) · potential to cause serious harm to themselves or others. |

Only a principal or acting principal can do this. Takes effect the day after the principal’s decision is made, the student may be made to leave on the same day. |

The student can return to school or kura on the date decided by the principal.

|

|

Suspension |

The formal removal of a student from school or kura by the principal, until the school board meets to decide what to do. |

The principal must determine whether a suspension is warranted on any of the grounds above. The personal circumstances of the child, and in which the incident or behaviour happened are also considered. |

Suspension meeting with the board, principal, and parents - an independent review of the principal’s decision. The principal is not involved in the decision but may attend. |

The board can decide to: - lift the suspension without conditions - lift the suspension with conditions - extend the suspension - exclude the child if under 16 - expel the child if over 16. |

|

Exclusion |

The formal removal of a student from school or kura if they are under 16 years. They must enrol in another school or kura. |

Same reasons as suspension but generally more severe. |

This is one outcome of a suspension meeting. |

The principal has 10 school days to try to arrange for the student to attend another school or kura. If they can’t do this, they must inform MoE who will then help. |

|

Expulsion |

The formal, permanent removal of a student from school or kura if they are 16 years old or older. |

Same reasons as suspension but generally more sever to result in expulsion. |

This is one outcome of a suspension meeting. |

The principal does not have to try to find another school or kura for the student but will inform MoE if the student wants to continue with their schooling. |

Chapter 2: Challenging behaviours in classrooms

Teachers, principals, and students face a wide range of challenging behaviours in their classrooms extremely frequently. Behaviours such as talking inappropriately are the most common, but even the most concerning behaviour (physically harming others) is seen every day by one in five teachers and principals. Time spent responding and managing behaviour takes away from time spent teaching and learning, impacting all students in the class.

This section sets out the types of challenging behaviours teachers face in the classroom and how often they happen.

Teachers and students face many different behaviours that are challenging in their classrooms, such as disruptions and a lack of student engagement. These behaviours directly impact teachers’ ability to teach, and all students’ progress and enjoyment of learning.

To understand what sorts of behaviour occur in classrooms in Aotearoa New Zealand and how often, we looked at:

- Ministry of Education statistics on the frequency of stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions, and expulsions(9)

- our surveys of teachers and principals

- our interviews with teachers, leaders, parents and whānau

- PISA data over the last decade.

This chapter sets out:

- how Aotearoa New Zealand compares to other countries

- what the challenging behaviours teachers and students face in the classroom are, and how often they are happening

- how classroom behaviour looks across different schools.

What we found: An overview

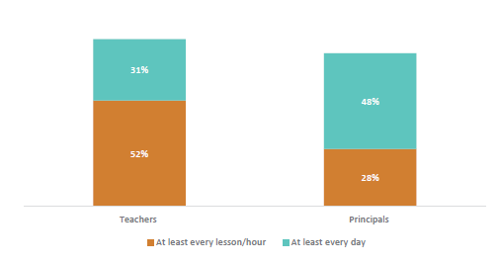

Teachers experience challenging behaviour in the classroom every day, most commonly dealing with students who talk inappropriately in class or distract others. Talking inappropriately in class is the most common form of challenging behaviour seen in the classroom, with over half of teachers (52 percent) dealing with this every lesson or hour. Next most common are distracting others (51 percent seeing every hour) and refusing to follow instructions (40 percent seeing every hour).

One in three teachers see behaviours that involve damaging or taking property every day and one in five see physically harming behaviours every day. One-third of teachers (32 percent) and a quarter of principals (23 percent) experience students damaging or taking property every day. One in five teachers (21 percent) and one in four principals (26 percent) see physically harming behaviours every day.

Challenging behaviours occur at a higher rate in Aotearoa New Zealand than other countries. In 2022, NZ had the worst behavioural climate in maths classes in the OECD. The most common behaviours reported were students being distracted by digital resources (46 percent report this happening in most or every lesson) and noise and disorder (43 percent).(10)

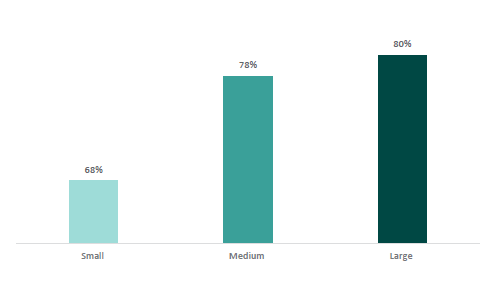

Behaviour is more of a problem at larger schools. Teachers at larger schools see challenging classroom behaviour more often than teachers at smaller schools. Eighty-three percent of teachers at large schools see behaviours that distract from learning at least every day compared to 72 percent of teachers at small schools.

1) How does Aotearoa New Zealand compare to other countries?

PISA results over the last 20 years show that Aotearoa New Zealand has consistently had a worse behaviour climate compared to most other OECD countries.

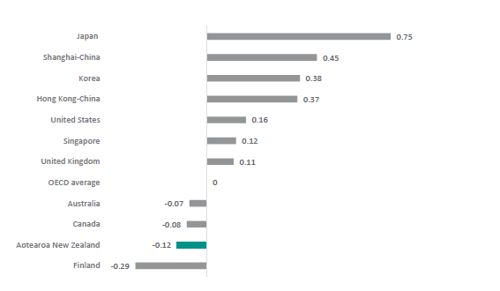

PISA 2000 showed that Aotearoa New Zealand 15-years-olds were sitting below the OECD average for school disciplinary climate and student related behaviours.(11) In addition, when the responses from Aotearoa New Zealand students were compared with other countries, Aotearoa New Zealand students generally reported that disruptive student behaviour hindered learning in their class to a greater extent.(12)

PISA 2003 also had a similar finding that both principals and students in Aotearoa New Zealand felt that the learning climate and discipline were worse in Aotearoa New Zealand than the average expressed across the OECD.(13)

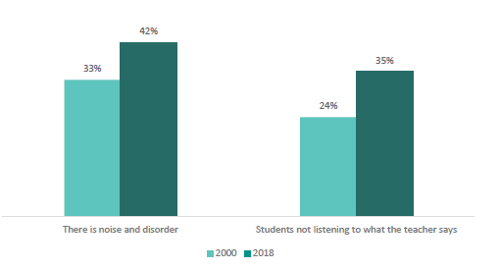

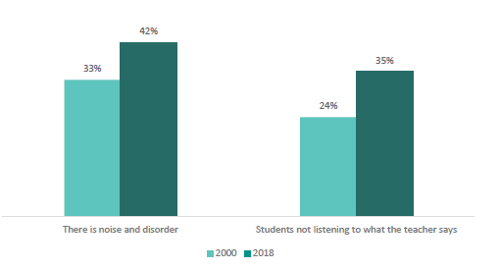

PISA 2009 again found something similar. Around one-third of Aotearoa New Zealand’s 15-year-olds reported that there were disciplinary issues in English classes in relation noise and disorder, teachers having to wait a long time for students to settle down, and students not listening to what teachers say(14). Overall, Aotearoa New Zealand 15-year-olds were more likely than the OECD average to report that there were disciplinary issues in their English classes.(15)

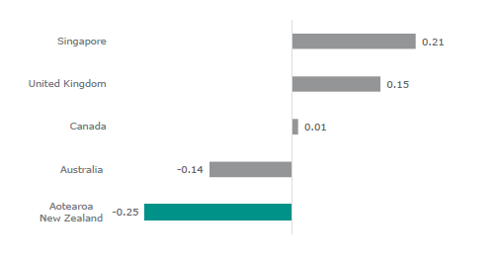

Figure 1: Mean index of disciplinary climate in English classes across some PISA countries 2009

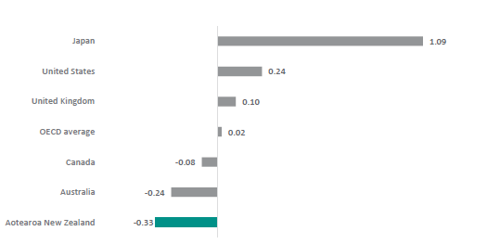

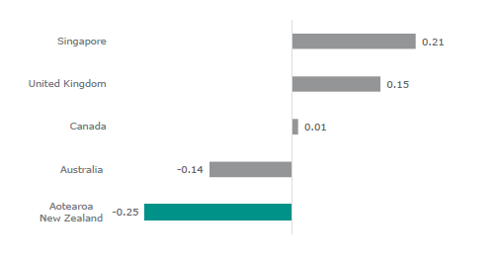

PISA 2012 continued this trend. Aotearoa New Zealand students reported more disruptive behaviour in their maths lessons than students in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Singapore in 2012.(16)

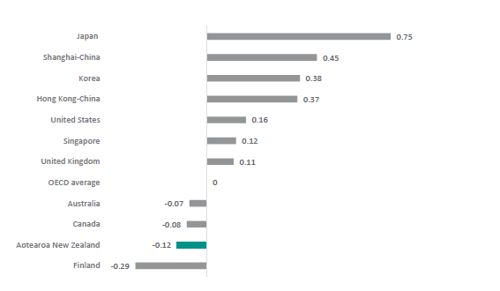

Figure 2: Mean index disciplinary climate score in maths lessons in 2012

PISA 2018 found the same results, with Aotearoa New Zealand sitting below the OECD average for behavioural climate, falling among the bottom quarter (twelfth from the bottom) of PISA countries for frequent behavioural issues in English classes. Relative to other countries, in Aotearoa New Zealand noise and disorder in classrooms is an especially common issue.(17)

Behaviour in Aotearoa New Zealand is still currently more problematic compared to other countries.

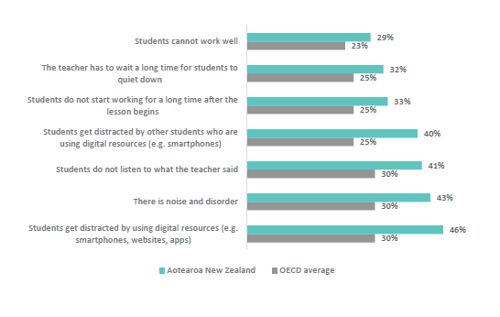

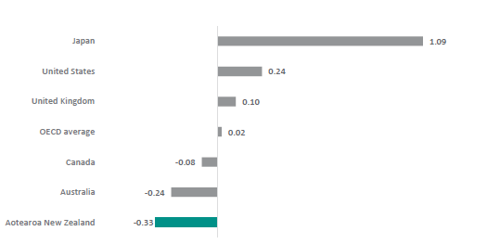

PISA 2022 found Aotearoa New Zealand scores the lowest out of all the OECD countries on the behavioural climate in maths classes, fourth from the bottom compared to all PISA countries.(18)

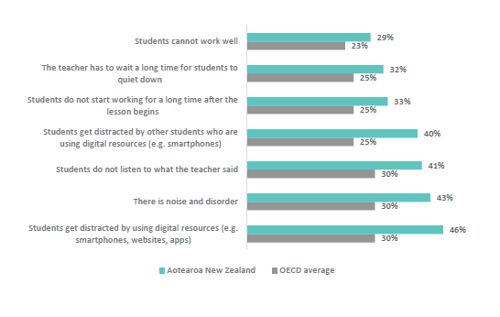

The most common behaviours reported were students being distracted by digital resources (for example smartphones, websites, and apps - 46 percent report this happening in most or every lesson) and noise and disorder (43 percent).

Compared to the OECD average, there was a greater proportion of students in Aotearoa New Zealand reporting all behaviours occurring in every or most maths lessons.

Figure 3: Proportion of students reporting ‘every lesson’ or ‘most lessons’ in maths classes 2022

Figure 4: Index of disciplinary climate in maths class across some OECD countries 2022 (higher numbers are better disciplinary climate, lower numbers are worse disciplinary climates)

2) What are the challenging behaviours teachers face in the classroom, and how often are they happening?

This section sets out what we know about how often students are engaging in five different types of behaviour:

- talking inappropriately in class

- distracting others

- refusing to follow instructions

- damaging or taking property

- physically harming others

- stand-downs, suspension, exclusions, and expulsions.

We asked teachers and principals how often they deal with these challenging behaviours. These five behaviours are set out in greater detail below.

We also looked at how many students are stood down, suspended, excluded, or expelled, and why.

The next sections share what we found about the frequency of each of these sets of challenging behaviours. Many of the behaviours overlap as the behaviours do not occur in isolation. For example, a student talking inappropriately in class may also be doing so in a way that distracts others.

a) Talking inappropriately in class

Taking inappropriately in class can take different forms in the classroom, such as calling out, shouting, and unauthorised talking to other students.

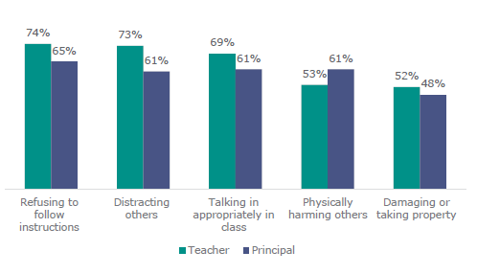

The most common behaviour teachers face is students talking inappropriately in class, with over three-quarters of teachers and principals seeing this every day.

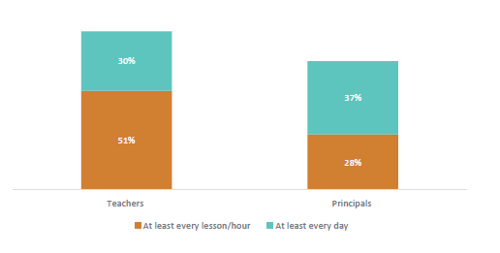

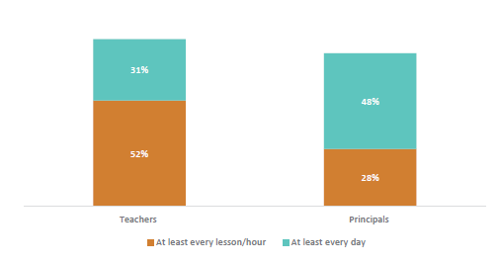

Four out of five teachers (83 percent) and three out of four principals (76 percent) see this behaviour at least every day. In addition to this, half of teachers (52 percent) and over a quarter of principals (28 percent) see this as often as every lesson/hour.

Figure 5: Frequency that talking inappropriately in class is seen by teachers and principals

In focus groups with teachers, students, and parents, we heard many examples of students talking inappropriately in class. Some things we heard about were high levels of students using disrespectful language and being rude to school staff, calling out across the classroom and over other students, and being rude to other students including swearing.

“In my classroom, it's probably my more challenging ones… [who] need to be centre of attention... [It’s] like an impulse control issue... Talking over you. Talking over each other.” (Teacher)

b) Distracting others

Behaviours that distract from learning take a range of forms in the classroom, including unauthorised use of phone/devices, attempting to distract others, and pulling faces.

Behaviours that distract students from their learning is the second most common behaviour, with over four in five teachers and two-thirds of principals experiencing this every day.

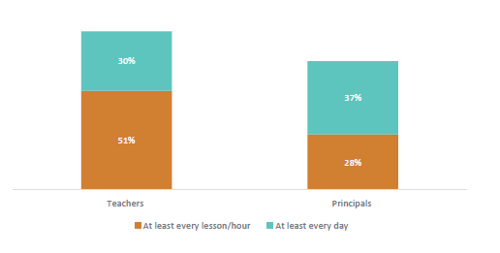

Four out of five teachers (81 percent) and two out of three principals (65 percent) see this behaviour every day. Half of teachers (51 percent) and just over a quarter of principals (28 percent) see this behaviour every lesson/hour.

Figure 6: Frequency that distracting behaviours in class is seen by teachers and principals

In focus groups with teachers, students, and parents, we heard examples of behaviours that distract themselves and others. Some of these examples included being disengaged from work and not being ready for tasks, an increase in students using devices at inappropriate times, an increase in the number of students feeling fatigued and unable to concentrate for long periods, and talking to their friends instead of working.

“Disrupting the learning of others… includes a whole range of things from being off task, falling out, chatting with somebody else near where you are or down the classroom, it could be throwing things. There's a whole variety that fits under that.” (Deputy principal)

“The classroom sizes are quite large and so you do have one or two [students] that can be disruptive to the class and take away from their learning. But I also know that my child also can lose focus and she can be quite disruptive as well.” (Parent)

c) Refusing to follow instructions

Behaviours that involve refusal to follow instructions include students being off task, ignoring requests, and unauthorised moving around the room.

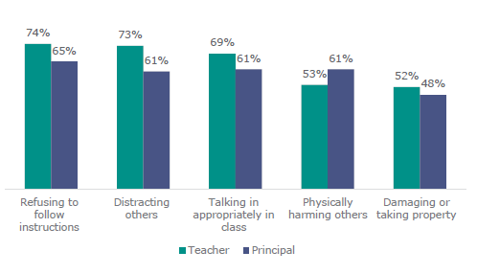

The third most common behaviour that teachers face is students refusing to follow instructions, with just under three-quarters of teachers and two-thirds of principals seeing this behaviour every day.

Three out of four teachers (73 percent) and two out of three principals (65 percent) experience students refusing to follow instructions every day. In addition to this, 40 percent of teachers and a quarter of principals (24 percent) see this behaviour every lesson/hour.

In focus groups with staff, students, and parents, we heard that this often involves students being off task, ignoring or verbally defying the teacher, and even leaving the classroom.

“Refusing to do… what they're told…. defiance… when you ask them to do something, they'll say ‘no’.” (Teacher)

“So one of the things we are noticing a lot with our kids entering in, is an inability to complete tasks and to follow simple instructions. We have a lot of our younger children and some of our older kids as well that opt out [of learning], and can opt out in a very disruptive manner… Refusal in varying ways. For the older children that I'm thinking about, it's often verbal, like, ‘No, I'm not doing it’. For things like our little ones, it will be removing themselves, running off out of the classroom, hiding in spaces, hiding under tables.” (Teacher)

d) Damaging or taking property

Behaviours that involve damaging or taking property include intentionally breaking classroom items, taking other people’s items without consent, and using classroom items without permission.

Damaging or taking others’ property is seen by a third of teachers and a quarter of principals every day.

A third of teachers (32 percent) and a quarter of principals (23 percent) experience students damaging or taking property every day, and one in 10 teachers (8 percent) and 4 percent of principals see this every lesson/hour.

In focus groups with teachers, students, and parents, we heard examples of behaviours that involve damaging or taking property. Teachers raised concerns about students throwing objects in class, such as chairs and kicking tables. Parents sometimes attribute these behaviours to a student’s lack of impulse control.

“My daughter tells me there's a student that goes in there and he will get aggressive, pick up desks and chairs and throw them… that disrupts their afternoon, their learning for the day because they're all talking about that rather than focusing on the actual learning.” (Parent)

e) Physically harming others

Behaviours that involve physically harming others include things such as hitting, kicking, punching, or biting others.

Students that physically harm others is the most extreme behaviour and one in five teachers and a quarter of principals experiencing this every day.

One in five teachers (21 percent) and one in four principals (26 percent) see this every day, while 2 percent of teachers and principals deal with this behaviour every lesson/hour.

In focus groups with teachers, students, and parents, we heard that these behaviours are extremely challenging and involve aggression, physical and extreme violence, and fighting with other students.

“We've had children come in [to school] with extreme violence with no empathy.” (Principal)

f) Stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions, and expulsions

There is variation in how schools choose to use these interventions, and they are not universally or consistently applied.(19) Because of this, these interventions are not a direct measure of extreme behaviour but are an indication of how often schools face student behaviour that is extremely challenging.

The following data comes from the Ministry of Education database on stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions, and expulsions.(20)

Stand-downs

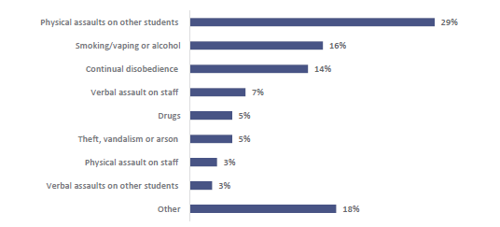

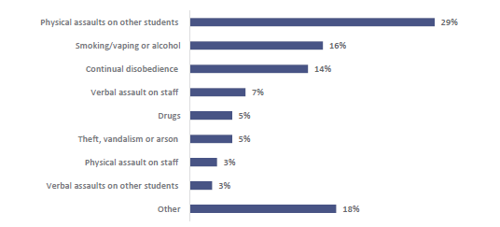

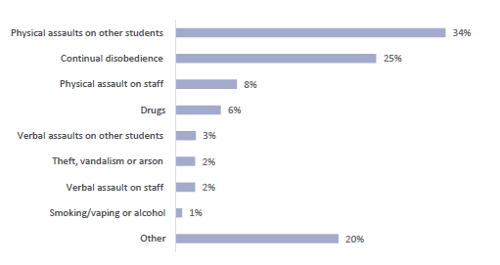

In 2022 there were 32.6 stand-downs per 1,000 students. The reasons for stand-downs are recorded by schools and are broken down by behaviour reason categories here:

- physical assaults on other students (9.6 stand-downs per 1000 students)

- smoking/vaping or alcohol (5.2 stand-downs per 1000 students)

- continual disobedience (4.6 stand-downs per 1000 students)

- verbal assault on staff (2.2 stand-downs per 1000 students)

- drugs (including substance abuse) (1.7 stand-downs per 1000 students)

- theft, vandalism, or arson (1.7 stand-downs per 1000 students)

- physical assault on staff (1.1 stand-downs per 1000 students)

- verbal assaults on other students (0.9 stand-downs per 1000 students)

- other which includes sexual harassment, sexual misconduct, weapons, and other harmful or dangerous behaviour (5.7 stand-downs per 1000 students).

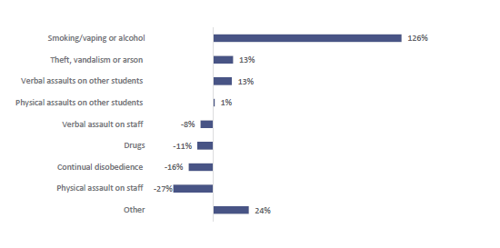

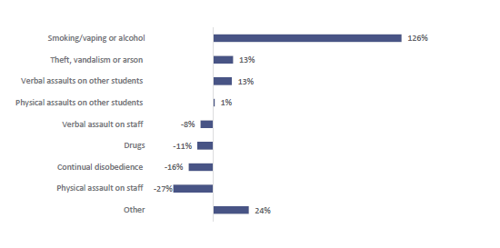

Figure 7: Percentage of students stood-down in 2022 by behaviour category

Suspensions

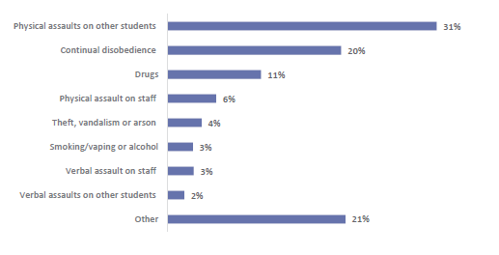

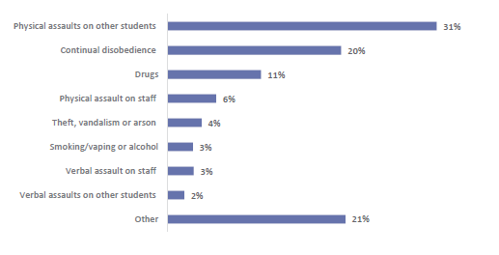

In 2022, there were 3.5 suspensions per 1,000 students. The reasons for suspensions are recorded by schools and are broken down by behaviour reason categories here:

- physical assaults on other students (1.1 suspensions per 1,000 students)

- drugs (0.4 suspensions per 1,000 students)

- continual disobedience (0.7 suspensions per 1,000 students)

- physical assault on staff (0.2 suspensions per 1,000 students)

- verbal assaults on other students (0.1 suspensions per 1,000 students)

- theft, vandalism, or arson (0.1 suspensions per 1,000 students)

- verbal assault on staff (0.1 suspensions per 1,000 students)

- smoking/vaping or alcohol (0.1 suspensions per 1,000 students)

- other (0.7 suspensions per 1,000 students).

Figure 8: Percentage of students suspended in 2022 by behaviour category

Exclusions

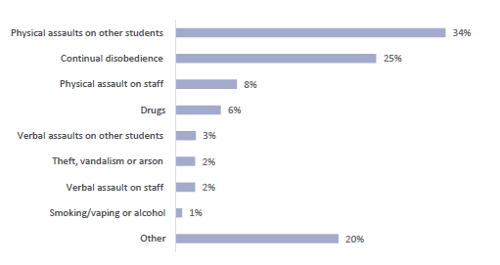

In 2022, there were 1.3 exclusions per 1,000 students. The reasons for exclusions are recorded by schools and are broken down by behaviour reason categories here:

- physical assaults on other students (0.4 exclusions per 1,000 students)

- continual disobedience (0.3 exclusions per 1,000 students)

- physical assault on staff (0.1 exclusions per 1,000 students)

- drugs (0.1 exclusions per 1,000 students)

- verbal assaults on other students (<0.1 exclusions per 1,000 students)

- theft, vandalism, or arson (<0.1 exclusions per 1,000 students)

- verbal assault on staff (<0.1 exclusions per 1,000 students)

- smoking/vaping or alcohol (<0.1 exclusions per 1,000 students)

- other (0.3 exclusions per 1,000 students).

Figure 9: Percentage of students excluded in 2022 by behaviour category

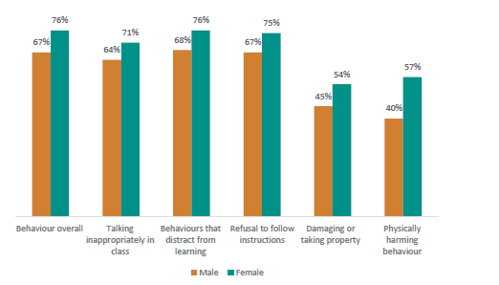

3) How is classroom behaviour different across schools?

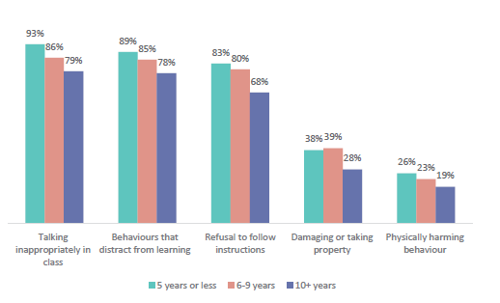

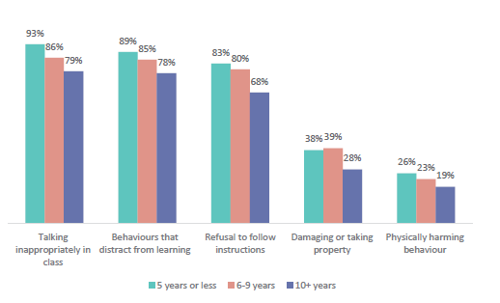

There are differences in the types and frequency that behaviours occur across different school contexts, with physical behaviours most common at primary, distraction most common at secondary, and greater behavioural problems at large schools and schools in low socioeconomic communities. Teachers with less experience also see challenging behaviours more frequently.

This section sets out what we know about the differences in behaviours occurring across:

- school age groups

- school size

- schools in high and low socioeconomic communities

- teachers’ experience.

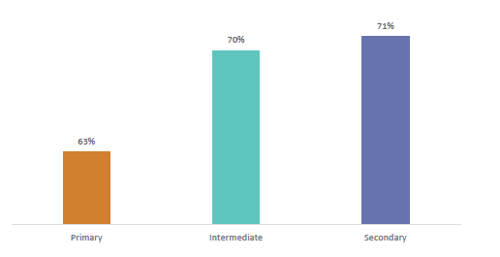

a) School age groups

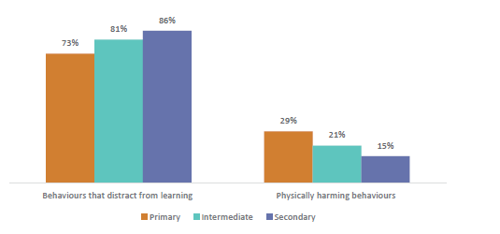

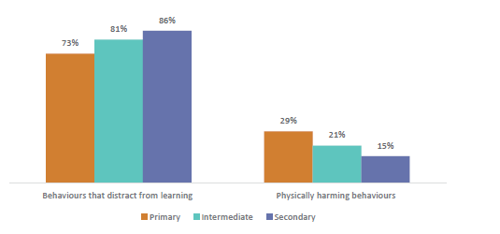

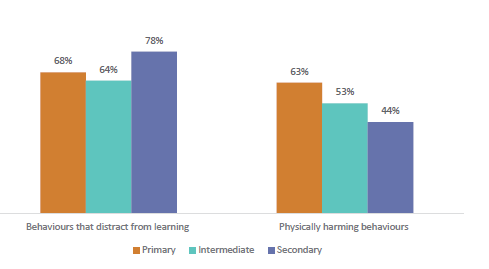

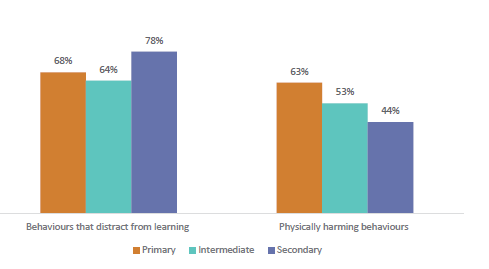

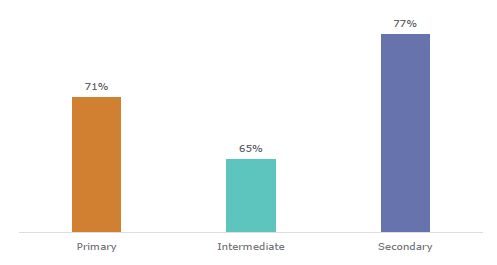

Physically harming behaviours are more common at primary schools.

Twice as many teachers see physically harming behaviours every day or more at primary school (29 percent) compared to secondary (15 percent), while intermediate schools sit in between (21 percent).

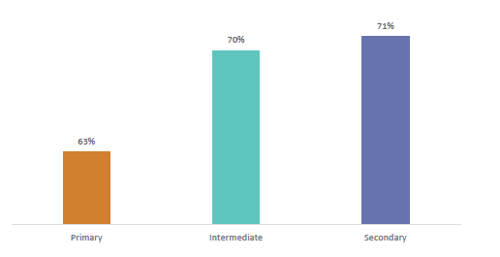

Behaviours that distract from learning are more frequent at secondary schools.

The most common challenging classroom behaviour seen by secondary school teachers are behaviours that distract from learning. Eighty-six percent of secondary teachers, 73 percent of primary, and 81 percent of intermediate teachers see behaviours that distract from learning every day or more. Further, teachers at secondary schools are 1.5 times more likely to see behaviours that distract from learning every hour (58 percent) than teachers at primary (40 percent) or intermediate schools (41 percent).

Behaviours, including behaviour problems, change with students’ age.(21) Physical behaviour is presenting more often in younger students as they are still developing the self-regulation required to control physical displays of behaviour. As they get older, problem behaviours are more likely to present as distracting behaviours.

Figure 10: Percent of teachers seeing behaviours every day or more across school age group

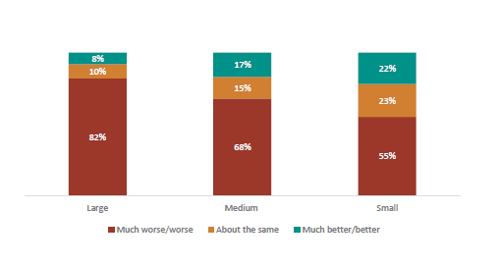

b) School size

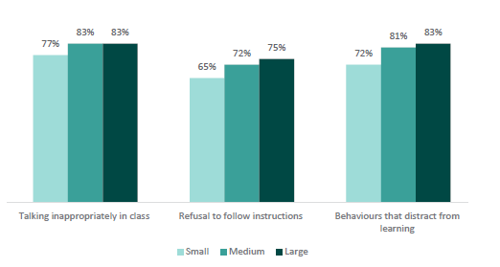

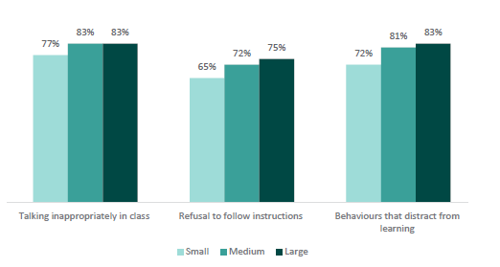

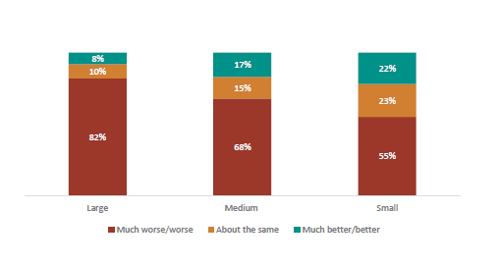

Behaviour is more of a problem at larger schools.

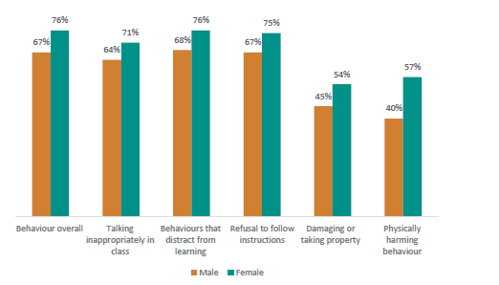

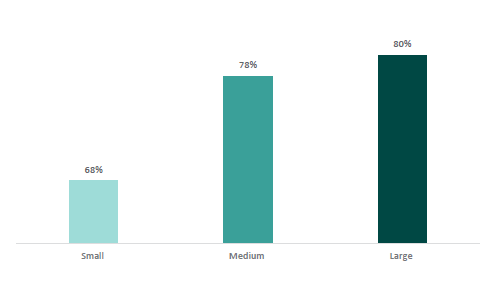

Teachers at larger schools see challenging classroom behaviours more often than teachers in smaller schools. Talking inappropriately in class is seen every day at 83 percent of large schools compared to 77 percent of small schools, as is refusal to follow instructions (75 percent compared to 65 percent), and behaviours that distract from learning (83 percent compared to 72 percent).

Figure 11: Percent of teachers seeing behaviours every day or more across school size