Related Insights

Explore related documents that you might be interested in.

Read Online

About this report

Oral language is foundational for children’s ongoing learning, through and beyond their early years.

ERO looked at how teachers and service leaders support children’s oral language in Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood services, and what good teaching practice looks like for supporting oral language development.

This report is focused on good practice for early childhood teachers and leaders. It uses robust evidence to clarify ‘what good looks like’ for supporting oral language, and how teachers and service leaders can implement good practices in their own service.

The Education Review Office (ERO) is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early childhood services, kura, and schools. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports early childhood services to provide quality education for children. In this case, we looked at how oral language in the early years is going currently, and what good practice for supporting oral language looks like.

|

This report is part of a set of two reports |

|

This good practice report is focused on what we found out about good practice for early childhood teachersa and service leaders. It is designed to be a practical resource. There is also a companion evaluation report which details what ERO found out about how oral language is currently going in Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood services. In Chapter 1, we give a brief overview of the findings of the evaluation report. |

What is oral language?

Language is key to human connection and communication. It is essential for people to navigate through the world effectively. People communicate in a variety of ways, ranging from gestures to written and oral language. Oral language includes:

→ listening (receptive language) skills: the ability to hear, process, and understand information

→ speaking (expressive language) skills: the ability to respond and make meaning with sounds, words, gestures, or signing.

Through listening and speaking, children learn to communicate their views, understand others, and make and share their discoveries. In Te Whāriki, Aotearoa New Zealand’s Early Childhood Education curriculum, oral language includes any method of communication the child uses in their first language.

|

Why is oral language important? |

|

Oral language is the foundation of literacy. Before children can read and write, they need to be able to understand language. Children’s early reading, writing, and comprehension skills all build on their oral language. Oral language development links to better outcomes in reading comprehension, articulation of thoughts and ideas, vocabulary, and grammar. Oral language helps children succeed at school. Oral language development in the early years makes a big difference to educational achievement later. It predicts academic success and retention rates at secondary school. Early measures of language, such as vocabulary at 2 years of age, predict academic achievement at 12 years of age and in secondary school. Oral language helps children collaborate and problem-solve. Oral language is used for sharing thoughts and transmitting knowledge. It is needed for conversational skills in small groups, including being able to initiate, join, and end conversations. It also helps children learn more effectively, apply their learning through problem-solving, and address challenges. Oral language skills help children communicate their needs and wants. Poor social communication skills in childhood relate to behavioural problems when children have difficulty communicating what they need and want, and get frustrated, which is estimated to affect up to 10 percent of children in Aotearoa New Zealand. |

What did ERO look at?

In ERO’s companion evaluation report, we explore a range of questions about what is happening with oral language in English-medium early childhood services in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Within this good practice report, our investigation explores:

→ what the existing research evidence says about good practice in supporting oral language in early childhood services

→ what the existing research evidence says about good support for teachers and service leaders

→ what these practices and supports look like in our Aotearoa New Zealand context, and across a range of early childhood service types and regions

→ what insights, strategies, and stories we could gather that could be useful for the sector – teachers, service leaders, parents and whānau, and early intervention services.

|

How does oral language fit in to Te Whāriki? |

|

Te Whāriki includes specific goals and outcomes related to oral language – such as developing non-verbal communication skills for a range of purposes (goal), and understanding oral language and using it for a range of purposes (learning outcome). The Mana Reo | Communication strand focuses on children’s communication skills, both spoken and non-spoken. As of May 2024, the principles, strands, goals, and learning outcomes of Te Whāriki are gazetted - which means that all licensed early childhood services are required to implement them. |

Where did ERO look?

We have taken a mixed-methods approach to deliver breadth and depth in this research. We built our understanding of the current state of oral language and what is good practice through literature review, surveys, interviews, and site visits.

We took a deep dive into the literature on good practice for supporting oral language. This covered both the national and international literature base.

To check our understanding and establish our supports, practice areas, and key practices, we worked closely with an Expert Advisory Group. The group included Aotearoa New Zealand academics, teachers, practitioners, and sector experts. We also worked with speech-language therapists over the course of this study.

In our fieldwork, we focused our investigation on the experiences of early childhood service leaders, teachers, and parents and whānau across Aotearoa New Zealand, in primarily English-medium settings. We also looked at some new entrant school classrooms in primary schools to further broaden our understanding. Our 16 site visits included a wide range of English-medium, teacher-led ECE services, including two Pacific services, one Steiner kindergarten and one Montessori preschool. In total, we heard from:

→ 43 early childhood service staff (including eight service leaders)

→ 25 school staff (including eight school leaders)

→ 15 parents and whānau.

As part of these conversations, we asked teachers and service leaders about ways that they bring evidence-based practices to life in their early childhood service.

We wanted to know about the particular strategies that have worked well in their experience. You can find their ideas in the ‘real-life strategies’ throughout Chapters 3 and 4 of this report. It is important to think about which of these strategies will be the right fit for each early childhood service, and how they might be adapted for particular communities of children and parents and whānau.

|

This report is not just about English language learning |

|

This evaluation draws on examples of practice from a range of ECE services, including education and care, home-based early childhood services, and kindergartens from rural areas, small towns, and cities in Aotearoa New Zealand. Our site visits took place in ‘English-medium’ (or ‘non-Māori medium’) services. (For resources specific to Māori-medium services, see the box below.) Some of our visits occurred in Pacific bilingual services, many of which ‘phase in’ English language learning over time. In Aotearoa New Zealand, all licensed ECE services are expected to provide opportunities for children to build their understanding of te reo Māori as well as English (and/or other languages relevant to the community), as part of the everyday experiences and learning that happen there. Ensuring children are able to access te reo Māori, and reflecting the cultures and languages of children and families, is required and affirmed by our guiding curriculum and regulatory frameworks. This is the rich oral language environment that children benefit from in ECE settings. While many of our examples of practice use the English language, it’s important to note that the key practices and supports that underpin our examples are from the international evidence base about oral language development. These draw on studies across a range of language contexts. The practices and supports have also been reviewed by Aotearoa New Zealand experts to ensure that they are relevant and useful for our bicultural context and diverse communities, and align to our curriculum and licensing requirements. |

|

ERO has additional resources that are specific to te reo Māori language learning |

|

As of 2020, over ten thousand children were undertaking their early learning education through te reo Māori most of the time. In these Māori-medium and Māori-immersion settings, children will learn through te reo Māori between 51 percent and 100 percent of the time. In kōhanga reo services, language acquisition and cultural acquisition are interlinked. Language acquisition within these settings is framed around whānau working to revitalise and strengthen te reo Māori me ōna tikanga – culture and language. A similar focus can be found within puna kōhungahunga, where language acquisition is part of a broader kaupapa Māori approach. In these spaces teachers and whānau work together to deliver culturally centred learning with te reo Māori as a key focus. ERO’s 2021 report, ‘Āhuru mōwai, Evaluation report for Te Kōhanga Reo’, examines how the Kōhanga Reo language approach supports the learning aspirations of children and their whānau. ERO’s 2016 report ‘Tuia te here tangata: Making meaningful connections’, explores Puna Reo practice, including language learning strategies and their impacts. ECE teachers may also find some value in ERO’s ‘Poutama Reo self-review framework’, which is designed for schools around supporting improvement in te reo Māori provision. These resources are linked in the ‘Useful Resources’ section of this report, as well as on our evidence website evidence.ero.govt.nz |

|

What about bilingual or multilingual children? |

|

It’s well-established in research that speaking more than one language has many learning advantages for young children, as well as ongoing life benefits. Around 200 languages are spoken in homes around Aotearoa New Zealand, and 18 percent of children between 0-14 years of age speak more than one language. Young children who are learning English as an additional language benefit cognitively from building their skills across multiple languages at the same time; it is a positive and useful process. The practices and supports highlighted in this report are relevant for teachers of all children, whether or not they have one, two, or more languages. It’s important for teachers to work in partnership with families and whānau to support children’s home languages. In the short term, it’s important for teachers to be aware that children learning more than one language might take longer than their single-language peers to grow their English word bank, combine words, build sentences, and speak clearly compared to children who have one language. This is normal and expected. They might also have stronger oral language skills or confidence in one language than the other, so teachers shouldn’t make assumptions about multilingual children’s oral language capability based on one language alone. |

ERO identified five key areas of practice and four supports

Below are the five evidence-based areas of practice and four evidence-based supports that we focus on in Chapters 3 and 4.

|

Good teaching practice areas |

Practice area 1 |

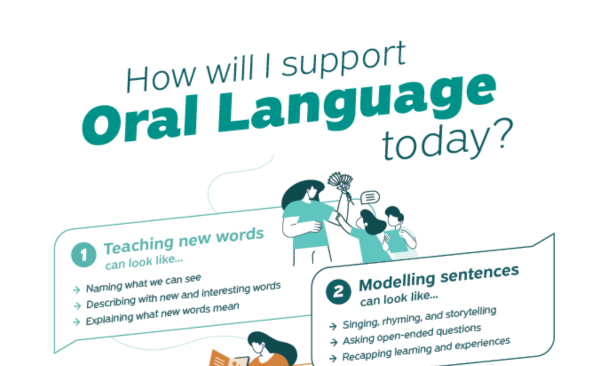

Teaching new words and how to use them This practice area includes intentionally using words to build a child’s understanding of words (their receptive vocabulary) and encouraging them to use and apply words in the right context (expressive vocabulary). |

|

Practice area 2 |

Modelling how words make sentences This practice area includes intentionally using language to show how words are put together to make sentences (grammar) and providing opportunities for children to use this in their own speech. |

|

|

Practice area 3 |

Reading interactively with children This practice area includes encouraging children to be active participants during book-reading. Teachers use prompts to encourage interactions between children and the person reading the book. |

|

|

Practice area 4 |

Using conversations to extend language This practice area includes intentionally using language to engage children in activities that are challenging for them. It encourages them to hear and use language to understand and share ideas, as well as reason with others. |

|

|

Practice area 5 |

Developing positive social communication This practice area includes providing opportunities for children to learn social norms and rules of communication – both verbal and non-verbal – so they can change the words they use, how quietly/loudly they speak, and how they position themselves when they listen and communicate with others, to understand and share ideas, as well as reason with others. |

|

Supports for good teaching practice |

Support 1 |

Early childhood service leadership and priorities This support is about early childhood service leaders providing teachers with the conditions and resources required for quality oral language support. |

|

Support 2 |

Teacher knowledge and assessment This support is about teachers’ professional knowledge about how children’s oral language is developed, taught, assessed, and supported. |

|

|

Support 3 |

Partnership with parents and whānau This support is about the partnerships that need to be in place with parents and whānau, to support oral language development at the early childhood service and at home. |

|

|

Support 4 |

Working with specialists This support is about teachers having a good understanding of when and how to work with specialists around oral language support. |

Report structure

This report is divided into four sections.

→ Chapter 1 sets out our key findings from our companion evaluation report, about the current state of oral language in Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood services.

→ Chapter 2 gives a brief overview of ERO’s recommended areas for action across Aotearoa New Zealand.

→ Chapter 3 is one of the main parts of the report. It sets out five areas of evidence-based teacher practice for supporting oral language development.

→ Chapter 4 is one of the main parts of the report. It sets out four evidence-based supports for oral language support that should be fostered in early childhood services.

As well as our companion evaluation report, ERO has also produced short practical guides for ECE teachers, ECE leaders, new entrant teachers, and parents and whānau, with guidance that is specific to their roles. These can all be downloaded from our website, evidence.ero.govt.nz

We appreciate the work of all those who supported this research, particularly the teachers, service leaders, parents and whānau, and experts who shared with us. Their experiences and insights are at the heart of what we have learnt.

Oral language is foundational for children’s ongoing learning, through and beyond their early years.

ERO looked at how teachers and service leaders support children’s oral language in Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood services, and what good teaching practice looks like for supporting oral language development.

This report is focused on good practice for early childhood teachers and leaders. It uses robust evidence to clarify ‘what good looks like’ for supporting oral language, and how teachers and service leaders can implement good practices in their own service.

The Education Review Office (ERO) is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early childhood services, kura, and schools. As part of this role, ERO looks at how the education system supports early childhood services to provide quality education for children. In this case, we looked at how oral language in the early years is going currently, and what good practice for supporting oral language looks like.

|

This report is part of a set of two reports |

|

This good practice report is focused on what we found out about good practice for early childhood teachersa and service leaders. It is designed to be a practical resource. There is also a companion evaluation report which details what ERO found out about how oral language is currently going in Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood services. In Chapter 1, we give a brief overview of the findings of the evaluation report. |

What is oral language?

Language is key to human connection and communication. It is essential for people to navigate through the world effectively. People communicate in a variety of ways, ranging from gestures to written and oral language. Oral language includes:

→ listening (receptive language) skills: the ability to hear, process, and understand information

→ speaking (expressive language) skills: the ability to respond and make meaning with sounds, words, gestures, or signing.

Through listening and speaking, children learn to communicate their views, understand others, and make and share their discoveries. In Te Whāriki, Aotearoa New Zealand’s Early Childhood Education curriculum, oral language includes any method of communication the child uses in their first language.

|

Why is oral language important? |

|

Oral language is the foundation of literacy. Before children can read and write, they need to be able to understand language. Children’s early reading, writing, and comprehension skills all build on their oral language. Oral language development links to better outcomes in reading comprehension, articulation of thoughts and ideas, vocabulary, and grammar. Oral language helps children succeed at school. Oral language development in the early years makes a big difference to educational achievement later. It predicts academic success and retention rates at secondary school. Early measures of language, such as vocabulary at 2 years of age, predict academic achievement at 12 years of age and in secondary school. Oral language helps children collaborate and problem-solve. Oral language is used for sharing thoughts and transmitting knowledge. It is needed for conversational skills in small groups, including being able to initiate, join, and end conversations. It also helps children learn more effectively, apply their learning through problem-solving, and address challenges. Oral language skills help children communicate their needs and wants. Poor social communication skills in childhood relate to behavioural problems when children have difficulty communicating what they need and want, and get frustrated, which is estimated to affect up to 10 percent of children in Aotearoa New Zealand. |

What did ERO look at?

In ERO’s companion evaluation report, we explore a range of questions about what is happening with oral language in English-medium early childhood services in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Within this good practice report, our investigation explores:

→ what the existing research evidence says about good practice in supporting oral language in early childhood services

→ what the existing research evidence says about good support for teachers and service leaders

→ what these practices and supports look like in our Aotearoa New Zealand context, and across a range of early childhood service types and regions

→ what insights, strategies, and stories we could gather that could be useful for the sector – teachers, service leaders, parents and whānau, and early intervention services.

|

How does oral language fit in to Te Whāriki? |

|

Te Whāriki includes specific goals and outcomes related to oral language – such as developing non-verbal communication skills for a range of purposes (goal), and understanding oral language and using it for a range of purposes (learning outcome). The Mana Reo | Communication strand focuses on children’s communication skills, both spoken and non-spoken. As of May 2024, the principles, strands, goals, and learning outcomes of Te Whāriki are gazetted - which means that all licensed early childhood services are required to implement them. |

Where did ERO look?

We have taken a mixed-methods approach to deliver breadth and depth in this research. We built our understanding of the current state of oral language and what is good practice through literature review, surveys, interviews, and site visits.

We took a deep dive into the literature on good practice for supporting oral language. This covered both the national and international literature base.

To check our understanding and establish our supports, practice areas, and key practices, we worked closely with an Expert Advisory Group. The group included Aotearoa New Zealand academics, teachers, practitioners, and sector experts. We also worked with speech-language therapists over the course of this study.

In our fieldwork, we focused our investigation on the experiences of early childhood service leaders, teachers, and parents and whānau across Aotearoa New Zealand, in primarily English-medium settings. We also looked at some new entrant school classrooms in primary schools to further broaden our understanding. Our 16 site visits included a wide range of English-medium, teacher-led ECE services, including two Pacific services, one Steiner kindergarten and one Montessori preschool. In total, we heard from:

→ 43 early childhood service staff (including eight service leaders)

→ 25 school staff (including eight school leaders)

→ 15 parents and whānau.

As part of these conversations, we asked teachers and service leaders about ways that they bring evidence-based practices to life in their early childhood service.

We wanted to know about the particular strategies that have worked well in their experience. You can find their ideas in the ‘real-life strategies’ throughout Chapters 3 and 4 of this report. It is important to think about which of these strategies will be the right fit for each early childhood service, and how they might be adapted for particular communities of children and parents and whānau.

|

This report is not just about English language learning |

|

This evaluation draws on examples of practice from a range of ECE services, including education and care, home-based early childhood services, and kindergartens from rural areas, small towns, and cities in Aotearoa New Zealand. Our site visits took place in ‘English-medium’ (or ‘non-Māori medium’) services. (For resources specific to Māori-medium services, see the box below.) Some of our visits occurred in Pacific bilingual services, many of which ‘phase in’ English language learning over time. In Aotearoa New Zealand, all licensed ECE services are expected to provide opportunities for children to build their understanding of te reo Māori as well as English (and/or other languages relevant to the community), as part of the everyday experiences and learning that happen there. Ensuring children are able to access te reo Māori, and reflecting the cultures and languages of children and families, is required and affirmed by our guiding curriculum and regulatory frameworks. This is the rich oral language environment that children benefit from in ECE settings. While many of our examples of practice use the English language, it’s important to note that the key practices and supports that underpin our examples are from the international evidence base about oral language development. These draw on studies across a range of language contexts. The practices and supports have also been reviewed by Aotearoa New Zealand experts to ensure that they are relevant and useful for our bicultural context and diverse communities, and align to our curriculum and licensing requirements. |

|

ERO has additional resources that are specific to te reo Māori language learning |

|

As of 2020, over ten thousand children were undertaking their early learning education through te reo Māori most of the time. In these Māori-medium and Māori-immersion settings, children will learn through te reo Māori between 51 percent and 100 percent of the time. In kōhanga reo services, language acquisition and cultural acquisition are interlinked. Language acquisition within these settings is framed around whānau working to revitalise and strengthen te reo Māori me ōna tikanga – culture and language. A similar focus can be found within puna kōhungahunga, where language acquisition is part of a broader kaupapa Māori approach. In these spaces teachers and whānau work together to deliver culturally centred learning with te reo Māori as a key focus. ERO’s 2021 report, ‘Āhuru mōwai, Evaluation report for Te Kōhanga Reo’, examines how the Kōhanga Reo language approach supports the learning aspirations of children and their whānau. ERO’s 2016 report ‘Tuia te here tangata: Making meaningful connections’, explores Puna Reo practice, including language learning strategies and their impacts. ECE teachers may also find some value in ERO’s ‘Poutama Reo self-review framework’, which is designed for schools around supporting improvement in te reo Māori provision. These resources are linked in the ‘Useful Resources’ section of this report, as well as on our evidence website evidence.ero.govt.nz |

|

What about bilingual or multilingual children? |

|

It’s well-established in research that speaking more than one language has many learning advantages for young children, as well as ongoing life benefits. Around 200 languages are spoken in homes around Aotearoa New Zealand, and 18 percent of children between 0-14 years of age speak more than one language. Young children who are learning English as an additional language benefit cognitively from building their skills across multiple languages at the same time; it is a positive and useful process. The practices and supports highlighted in this report are relevant for teachers of all children, whether or not they have one, two, or more languages. It’s important for teachers to work in partnership with families and whānau to support children’s home languages. In the short term, it’s important for teachers to be aware that children learning more than one language might take longer than their single-language peers to grow their English word bank, combine words, build sentences, and speak clearly compared to children who have one language. This is normal and expected. They might also have stronger oral language skills or confidence in one language than the other, so teachers shouldn’t make assumptions about multilingual children’s oral language capability based on one language alone. |

ERO identified five key areas of practice and four supports

Below are the five evidence-based areas of practice and four evidence-based supports that we focus on in Chapters 3 and 4.

|

Good teaching practice areas |

Practice area 1 |

Teaching new words and how to use them This practice area includes intentionally using words to build a child’s understanding of words (their receptive vocabulary) and encouraging them to use and apply words in the right context (expressive vocabulary). |

|

Practice area 2 |

Modelling how words make sentences This practice area includes intentionally using language to show how words are put together to make sentences (grammar) and providing opportunities for children to use this in their own speech. |

|

|

Practice area 3 |

Reading interactively with children This practice area includes encouraging children to be active participants during book-reading. Teachers use prompts to encourage interactions between children and the person reading the book. |

|

|

Practice area 4 |

Using conversations to extend language This practice area includes intentionally using language to engage children in activities that are challenging for them. It encourages them to hear and use language to understand and share ideas, as well as reason with others. |

|

|

Practice area 5 |

Developing positive social communication This practice area includes providing opportunities for children to learn social norms and rules of communication – both verbal and non-verbal – so they can change the words they use, how quietly/loudly they speak, and how they position themselves when they listen and communicate with others, to understand and share ideas, as well as reason with others. |

|

Supports for good teaching practice |

Support 1 |

Early childhood service leadership and priorities This support is about early childhood service leaders providing teachers with the conditions and resources required for quality oral language support. |

|

Support 2 |

Teacher knowledge and assessment This support is about teachers’ professional knowledge about how children’s oral language is developed, taught, assessed, and supported. |

|

|

Support 3 |

Partnership with parents and whānau This support is about the partnerships that need to be in place with parents and whānau, to support oral language development at the early childhood service and at home. |

|

|

Support 4 |

Working with specialists This support is about teachers having a good understanding of when and how to work with specialists around oral language support. |

Report structure

This report is divided into four sections.

→ Chapter 1 sets out our key findings from our companion evaluation report, about the current state of oral language in Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood services.

→ Chapter 2 gives a brief overview of ERO’s recommended areas for action across Aotearoa New Zealand.

→ Chapter 3 is one of the main parts of the report. It sets out five areas of evidence-based teacher practice for supporting oral language development.

→ Chapter 4 is one of the main parts of the report. It sets out four evidence-based supports for oral language support that should be fostered in early childhood services.

As well as our companion evaluation report, ERO has also produced short practical guides for ECE teachers, ECE leaders, new entrant teachers, and parents and whānau, with guidance that is specific to their roles. These can all be downloaded from our website, evidence.ero.govt.nz

We appreciate the work of all those who supported this research, particularly the teachers, service leaders, parents and whānau, and experts who shared with us. Their experiences and insights are at the heart of what we have learnt.

Chapter 1: What do we know about oral language in our early childhood services?

ERO looked at how well oral language learning is going in Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood services. These findings are set out in more detail in our companion evaluation report, Let’s keep talking: Oral language development in the early years.

This chapter gives a brief overview of our 18 key findings.

ERO identified 18 key findings about the state of oral language in Aotearoa

New Zealand early childhood services. For more detail and additional findings, see our companion evaluation report: Let’s keep talking: Oral language development in the early years.

Key findings

Oral language is critical for achieving the Government’s literacy ambitions.

Finding 1: Oral language is critical for later literacy and education outcomes. It also plays a key role in developing key social-emotional skills that support behaviour. Children’s vocabulary at age 2 is strongly linked to their literacy and numeracy achievement at age 12, and delays in oral language in the early years are reflected in poor reading comprehension at school.

Most children’s oral language is developing well, but there is a significant group of children who are behind and Covid-19 has made this worse.

Finding 2: A large Aotearoa New Zealand study found 80 percent of children at age 5 are doing well, but 20 percent are struggling with oral language. ECE and new entrant teachers also report that a group of children are struggling and half of parents and whānau report their child has some difficulty with oral language in the early years.

Finding 3: Covid-19 has had a significant impact. Nearly two-thirds of teachers (59 percent of ECE teachers and 65 percent of new entrant teachers) report that Covid-19 has impacted children’s language development. Teachers told us that social communication was particularly impacted by Covid-19, particularly language skills for social communication. International studies confirm the significant impact of Covid-19 on language development.

Figure 1: Percentage of teachers reporting Covid-19 had an impact on children’s oral language development

"A lot of children are not able to communicate their needs. They are difficult to understand when they speak. They are not used to having conversations." (Teacher)

Children from low socio-economic backgrounds and boys are struggling the most.

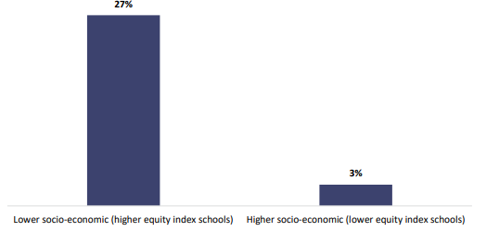

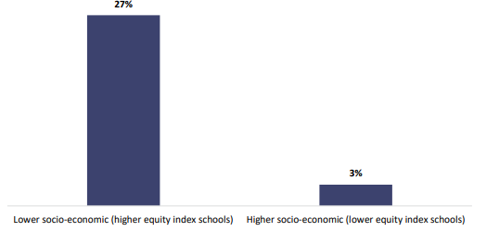

Finding 4: Evidence both in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally is clear that children from lower socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to struggle with oral language skills. We found that new entrant teachers we surveyed in schools in low socio-economic communities were nine times more likely to report children being below expected levels of oral language. Parents and whānau with lower qualifications were also more likely to report that their child has difficulty with oral language.

Figure 2: New entrant teachers reporting that most children they work with are below the expected level of oral language, by socio-economic community

Finding 5: Both in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally, boys have more difficulty developing oral language than girls. Parents and whānau we surveyed reported 70 percent of boys are not at the expected development level, compared with 56 percent of girls.

Figure 3: Proportion of parents and whānau that report their child has some difficulty in oral language

Difficulties with oral language emerge as children develop and oral language becomes more complex.

Finding 6: Teachers and parents and whānau report more concerns about children being behind as they become older and start school. For example, 56 percent of parents and whānau report their child has difficulty as a toddler (aged 18 months to three years old), compared to over two-thirds of parents and whānau (70 percent) reporting that their child has difficulty as a preschooler (aged three to five).

Finding 7: Teachers and parents and whānau report that children who are behind most often struggle with constructing sentences, telling stories, and using social communication to talk about their thoughts and feelings. For example, 43 percent of parents and whānau report their child has some difficulty with oral grammar, but only 13 percent report difficulty with gestures.

Figure 4: Proportion of parents and whānau who report their toddler or preschooler has difficulty with oral language

Quality ECE makes a difference, particularly to children in low socio-economic communities, but they attend ECE less often.

Finding 8: International studies find that quality ECE supports language development and can accelerate literacy by up to a year (particularly for children in low socio-economic communities), and that quality ECE leads to better academic achievement at age 16 for children from low socio-economic communities.

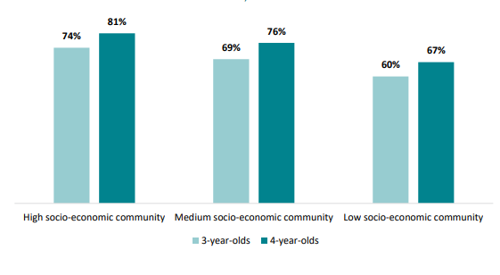

Finding 9: Children from low socio-economic communities attend ECE for fewer hours than children in high socio-economic areas, which can be due to a range of factors.

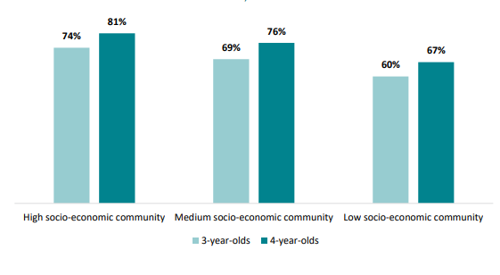

Figure 5: Intensity of ECE participation of 3- and 4-year-olds in 2023, by socio-economic community

The evidence is clear about the practices that matter for language development, and most teachers report using them frequently.

Finding 10: International and Aotearoa New Zealand evidence is clear that the practices that best support the development of oral language skills are:

|

Practice area 1 |

Teaching new words and how to use them |

|

Practice area 2 |

Modelling how words make sentences |

|

Practice area 3 |

Reading interactively with children |

|

Practice area 4 |

Using conversation to extend language |

|

Practice area 5 |

Developing positive social communication |

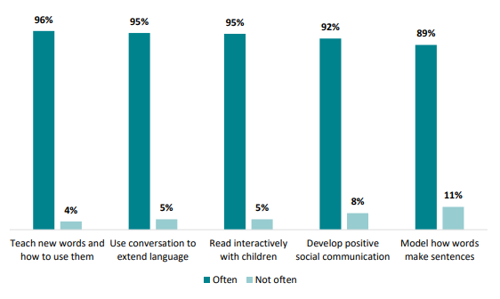

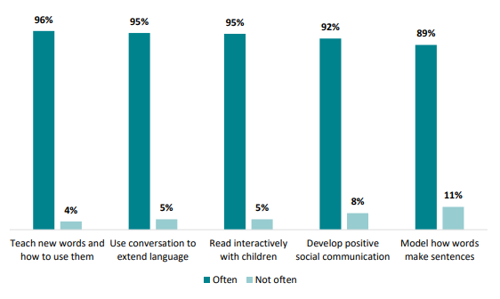

Finding 11: ECE and new entrant teachers we surveyed reported they use these evidence-based practices often. ECE teachers reported that they most often teach new words and how to use them (96 percent), use conversation to extend language (95 percent), and read interactively with children (95 percent). New entrant teachers we surveyed reported they most frequently read interactively with children (99 percent), teach new words and how to use them (96 percent), and model how words make sentences (95 percent).

Figure 6: ECE teachers’ reported frequency of using teaching practices

Teachers’ practices to develop social communication are weaker.

Finding 12: ECE and new entrant teachers we surveyed both reported to us they develop social communication skills least frequently.

Professional knowledge is the strongest driver of teachers using evidence- based good practices. Qualified ECE teachers reported being almost twice as confident in their knowledge about oral language.

Finding 13: Qualified ECE teachers we surveyed reported being almost twice as confident in their knowledge about how oral language develops than non-qualified teachers. Most qualified ECE teachers (94 percent) reported being confident, but only two-thirds (64 percent) of non-qualified teachers reported being confident.

Finding 14: Qualified teachers reported more frequently using key practices, for example, using conversation to extend language (96 percent compared with 92 percent of non-qualified teachers).

Finding 15: ECE teachers who reported being extremely confident in their professional knowledge of how children’s language develops were up to seven times more likely to report using effective teaching practices regularly.

Figure 7: ECE teachers’ reported confidence in their professional knowledge of how oral language develops, qualified compared with non-qualified teachers

“We got the [provider] to come in and talk to us about the science, and the brain, and the neuroscience behind basically play-based learning.” (Teacher)

“You know that you are using this strategy that is researched and proven to work.” (Teacher)

Teachers and parents often do not know how well their children are developing and this matters as timely support can prevent problems later.

Finding 16: Not all ECE and new entrant teachers are confident to assess oral language progress. Of the new entrant teachers we surveyed, a quarter reported not being confident to assess and report on progress. The lack of clear development expectations and milestones, and lack of alignment between Te Whāriki and the New Zealand Curriculum, makes this difficult. Half of parents (53 percent) do not get information from their service about their child’s oral language progress.

Finding 17: Being able to assess children’s oral language progress and identify potential difficulties is an important part of teaching young children. However, not all ECE and new entrant teachers are confident to identify difficulties in oral language (15 percent of ECE teachers and 24 percent of new entrant teachers surveyed report not being confident).

Figure 8: ECE teachers' and new entrant teachers' reported confidence to identify difficulties in children's oral language development

Finding 18: For children who are struggling, support from specialists, such as speech-language therapists, who can help with oral language development is key. But not all teachers are confident to work with these specialists, with 12 percent of ECE teachers and 17 percent of new entrant teachers reporting not being confident.

“Many are attending ECE, but not being referred early enough once the delay in oral language is noticed. Then when trying to get intervention, the wait times are too long and the support is inconsistent.” (New entrant teacher)

Conclusion

Oral language in our Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood services is a significant problem, and it has been getting worse. We know that oral language in the early years predicts outcomes later in life. More needs to be done to ensure that oral language support is effective, well-supported, and embedded across our early childhood services.

In the next sections of this report, we set out what actions ERO is recommending at the higher level to support services (Chapter 2), and what teachers (Chapter 3) and service leaders (Chapter 4) and can do to improve oral language teaching.

ERO looked at how well oral language learning is going in Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood services. These findings are set out in more detail in our companion evaluation report, Let’s keep talking: Oral language development in the early years.

This chapter gives a brief overview of our 18 key findings.

ERO identified 18 key findings about the state of oral language in Aotearoa

New Zealand early childhood services. For more detail and additional findings, see our companion evaluation report: Let’s keep talking: Oral language development in the early years.

Key findings

Oral language is critical for achieving the Government’s literacy ambitions.

Finding 1: Oral language is critical for later literacy and education outcomes. It also plays a key role in developing key social-emotional skills that support behaviour. Children’s vocabulary at age 2 is strongly linked to their literacy and numeracy achievement at age 12, and delays in oral language in the early years are reflected in poor reading comprehension at school.

Most children’s oral language is developing well, but there is a significant group of children who are behind and Covid-19 has made this worse.

Finding 2: A large Aotearoa New Zealand study found 80 percent of children at age 5 are doing well, but 20 percent are struggling with oral language. ECE and new entrant teachers also report that a group of children are struggling and half of parents and whānau report their child has some difficulty with oral language in the early years.

Finding 3: Covid-19 has had a significant impact. Nearly two-thirds of teachers (59 percent of ECE teachers and 65 percent of new entrant teachers) report that Covid-19 has impacted children’s language development. Teachers told us that social communication was particularly impacted by Covid-19, particularly language skills for social communication. International studies confirm the significant impact of Covid-19 on language development.

Figure 1: Percentage of teachers reporting Covid-19 had an impact on children’s oral language development

"A lot of children are not able to communicate their needs. They are difficult to understand when they speak. They are not used to having conversations." (Teacher)

Children from low socio-economic backgrounds and boys are struggling the most.

Finding 4: Evidence both in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally is clear that children from lower socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to struggle with oral language skills. We found that new entrant teachers we surveyed in schools in low socio-economic communities were nine times more likely to report children being below expected levels of oral language. Parents and whānau with lower qualifications were also more likely to report that their child has difficulty with oral language.

Figure 2: New entrant teachers reporting that most children they work with are below the expected level of oral language, by socio-economic community

Finding 5: Both in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally, boys have more difficulty developing oral language than girls. Parents and whānau we surveyed reported 70 percent of boys are not at the expected development level, compared with 56 percent of girls.

Figure 3: Proportion of parents and whānau that report their child has some difficulty in oral language

Difficulties with oral language emerge as children develop and oral language becomes more complex.

Finding 6: Teachers and parents and whānau report more concerns about children being behind as they become older and start school. For example, 56 percent of parents and whānau report their child has difficulty as a toddler (aged 18 months to three years old), compared to over two-thirds of parents and whānau (70 percent) reporting that their child has difficulty as a preschooler (aged three to five).

Finding 7: Teachers and parents and whānau report that children who are behind most often struggle with constructing sentences, telling stories, and using social communication to talk about their thoughts and feelings. For example, 43 percent of parents and whānau report their child has some difficulty with oral grammar, but only 13 percent report difficulty with gestures.

Figure 4: Proportion of parents and whānau who report their toddler or preschooler has difficulty with oral language

Quality ECE makes a difference, particularly to children in low socio-economic communities, but they attend ECE less often.

Finding 8: International studies find that quality ECE supports language development and can accelerate literacy by up to a year (particularly for children in low socio-economic communities), and that quality ECE leads to better academic achievement at age 16 for children from low socio-economic communities.

Finding 9: Children from low socio-economic communities attend ECE for fewer hours than children in high socio-economic areas, which can be due to a range of factors.

Figure 5: Intensity of ECE participation of 3- and 4-year-olds in 2023, by socio-economic community

The evidence is clear about the practices that matter for language development, and most teachers report using them frequently.

Finding 10: International and Aotearoa New Zealand evidence is clear that the practices that best support the development of oral language skills are:

|

Practice area 1 |

Teaching new words and how to use them |

|

Practice area 2 |

Modelling how words make sentences |

|

Practice area 3 |

Reading interactively with children |

|

Practice area 4 |

Using conversation to extend language |

|

Practice area 5 |

Developing positive social communication |

Finding 11: ECE and new entrant teachers we surveyed reported they use these evidence-based practices often. ECE teachers reported that they most often teach new words and how to use them (96 percent), use conversation to extend language (95 percent), and read interactively with children (95 percent). New entrant teachers we surveyed reported they most frequently read interactively with children (99 percent), teach new words and how to use them (96 percent), and model how words make sentences (95 percent).

Figure 6: ECE teachers’ reported frequency of using teaching practices

Teachers’ practices to develop social communication are weaker.

Finding 12: ECE and new entrant teachers we surveyed both reported to us they develop social communication skills least frequently.

Professional knowledge is the strongest driver of teachers using evidence- based good practices. Qualified ECE teachers reported being almost twice as confident in their knowledge about oral language.

Finding 13: Qualified ECE teachers we surveyed reported being almost twice as confident in their knowledge about how oral language develops than non-qualified teachers. Most qualified ECE teachers (94 percent) reported being confident, but only two-thirds (64 percent) of non-qualified teachers reported being confident.

Finding 14: Qualified teachers reported more frequently using key practices, for example, using conversation to extend language (96 percent compared with 92 percent of non-qualified teachers).

Finding 15: ECE teachers who reported being extremely confident in their professional knowledge of how children’s language develops were up to seven times more likely to report using effective teaching practices regularly.

Figure 7: ECE teachers’ reported confidence in their professional knowledge of how oral language develops, qualified compared with non-qualified teachers

“We got the [provider] to come in and talk to us about the science, and the brain, and the neuroscience behind basically play-based learning.” (Teacher)

“You know that you are using this strategy that is researched and proven to work.” (Teacher)

Teachers and parents often do not know how well their children are developing and this matters as timely support can prevent problems later.

Finding 16: Not all ECE and new entrant teachers are confident to assess oral language progress. Of the new entrant teachers we surveyed, a quarter reported not being confident to assess and report on progress. The lack of clear development expectations and milestones, and lack of alignment between Te Whāriki and the New Zealand Curriculum, makes this difficult. Half of parents (53 percent) do not get information from their service about their child’s oral language progress.

Finding 17: Being able to assess children’s oral language progress and identify potential difficulties is an important part of teaching young children. However, not all ECE and new entrant teachers are confident to identify difficulties in oral language (15 percent of ECE teachers and 24 percent of new entrant teachers surveyed report not being confident).

Figure 8: ECE teachers' and new entrant teachers' reported confidence to identify difficulties in children's oral language development

Finding 18: For children who are struggling, support from specialists, such as speech-language therapists, who can help with oral language development is key. But not all teachers are confident to work with these specialists, with 12 percent of ECE teachers and 17 percent of new entrant teachers reporting not being confident.

“Many are attending ECE, but not being referred early enough once the delay in oral language is noticed. Then when trying to get intervention, the wait times are too long and the support is inconsistent.” (New entrant teacher)

Conclusion

Oral language in our Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood services is a significant problem, and it has been getting worse. We know that oral language in the early years predicts outcomes later in life. More needs to be done to ensure that oral language support is effective, well-supported, and embedded across our early childhood services.

In the next sections of this report, we set out what actions ERO is recommending at the higher level to support services (Chapter 2), and what teachers (Chapter 3) and service leaders (Chapter 4) and can do to improve oral language teaching.

Chapter 2: What does ERO recommend for change?

This good practice report is focused on what ECE leaders and teachers can do to impact children’s oral language development within their early childhood services. However, we know that improving oral language isn’t just up to early childhood services – it requires shared responsibility and deliberate, joint actions.

Based on what we found out about the state of oral language across Aotearoa New Zealand, ERO is recommending changes to the supports and structures available to services. In this section, we outline the five areas that require action across agencies, to ensure all ECE services are well set up to support oral language – and to be able to focus on great teaching and learning.

ECE teachers and service leaders can make a big difference through their everyday practices and priorities. The most powerful service-level practices for supporting children’s oral language are set out in Chapters 3 and 4 of this report.

However, the significance of the oral language challenges that ERO identified (detailed in our companion evaluation report and summarised in Chapter 1 of this report) need strong and decisive actions to enable ECE services to do their best work in supporting children’s oral language. In this chapter, we outline the five action areas that ERO is putting forward as recommendations for a cross-agency response.

ERO’s recommendations

ERO has identified five areas for action, and 10 recommendations, to support children’s oral language development.

|

Area 1: Increase participation in quality ECE for children from low socio-economic communities |

|

1) Increase participation in quality ECE for children from low socio-economic communities through removing barriers. 2) Raise the quality of ECE for children in low socio-economic communities – including through ERO reviews and Ministry of Education interventions. |

|

Area 2: Put in place clear and consistent expectations and track children’s progress |

|

3) Review how the New Zealand Curriculum at the start of school and Te Whāriki work together to provide clear and consistent progress indicators for oral language. 4) Make sure there are good tools that are used by ECE teachers to track progress and identify difficulties in children’s language development. 5) Assess children’s oral language at the start of school to help teachers to identify any tailored support or approaches they may need. |

|

Area 3: Increase teachers’ use of effective practices |

|

6) In initial teacher education for ECE and new entrant teachers, have a clear focus on the evidence-based practices that support oral language development. 7) Increase professional knowledge of oral language development, in particular for non-qualified ECE teachers, through effective professional learning and development. |

|

Area 4: Support parents and whānau to develop language at home |

|

8) Support ECE services to provide regular updates on children’s oral language development to parents and whānau. 9) Support ECE services in low socio-economic communities to provide resources to parents and whānau to use with their children. |

|

Area 5: Increase targeted support |

|

10) Invest in targeted programmes and approaches that prevent and address delays in language development (e.g., Oral Language and Literacy Initiative and Better Start Literacy Approach). |

Conclusion

Oral language is a critical building block for all children and essential to setting them up to succeed at school and beyond. More needs to be done to ensure that oral language support is effective, well-supported, and embedded across our early childhood services. Quality ECE can make a difference.

We have identified five key areas of action to support children’s oral language development. Together, these areas of action can help address the oral language challenges children face.

In the next sections of this report, we set out practical guidance for teachers (Chapter 3) and service leaders (Chapter 4) to take their own actions to improve oral language support.

This good practice report is focused on what ECE leaders and teachers can do to impact children’s oral language development within their early childhood services. However, we know that improving oral language isn’t just up to early childhood services – it requires shared responsibility and deliberate, joint actions.

Based on what we found out about the state of oral language across Aotearoa New Zealand, ERO is recommending changes to the supports and structures available to services. In this section, we outline the five areas that require action across agencies, to ensure all ECE services are well set up to support oral language – and to be able to focus on great teaching and learning.

ECE teachers and service leaders can make a big difference through their everyday practices and priorities. The most powerful service-level practices for supporting children’s oral language are set out in Chapters 3 and 4 of this report.

However, the significance of the oral language challenges that ERO identified (detailed in our companion evaluation report and summarised in Chapter 1 of this report) need strong and decisive actions to enable ECE services to do their best work in supporting children’s oral language. In this chapter, we outline the five action areas that ERO is putting forward as recommendations for a cross-agency response.

ERO’s recommendations

ERO has identified five areas for action, and 10 recommendations, to support children’s oral language development.

|

Area 1: Increase participation in quality ECE for children from low socio-economic communities |

|

1) Increase participation in quality ECE for children from low socio-economic communities through removing barriers. 2) Raise the quality of ECE for children in low socio-economic communities – including through ERO reviews and Ministry of Education interventions. |

|

Area 2: Put in place clear and consistent expectations and track children’s progress |

|

3) Review how the New Zealand Curriculum at the start of school and Te Whāriki work together to provide clear and consistent progress indicators for oral language. 4) Make sure there are good tools that are used by ECE teachers to track progress and identify difficulties in children’s language development. 5) Assess children’s oral language at the start of school to help teachers to identify any tailored support or approaches they may need. |

|

Area 3: Increase teachers’ use of effective practices |

|

6) In initial teacher education for ECE and new entrant teachers, have a clear focus on the evidence-based practices that support oral language development. 7) Increase professional knowledge of oral language development, in particular for non-qualified ECE teachers, through effective professional learning and development. |

|

Area 4: Support parents and whānau to develop language at home |

|

8) Support ECE services to provide regular updates on children’s oral language development to parents and whānau. 9) Support ECE services in low socio-economic communities to provide resources to parents and whānau to use with their children. |

|

Area 5: Increase targeted support |

|

10) Invest in targeted programmes and approaches that prevent and address delays in language development (e.g., Oral Language and Literacy Initiative and Better Start Literacy Approach). |

Conclusion

Oral language is a critical building block for all children and essential to setting them up to succeed at school and beyond. More needs to be done to ensure that oral language support is effective, well-supported, and embedded across our early childhood services. Quality ECE can make a difference.

We have identified five key areas of action to support children’s oral language development. Together, these areas of action can help address the oral language challenges children face.

In the next sections of this report, we set out practical guidance for teachers (Chapter 3) and service leaders (Chapter 4) to take their own actions to improve oral language support.

Chapter 3: How can teachers support children's oral language development?

Oral language is foundational for children’s ongoing learning, through and beyond their early years. ERO reviewed international and local evidence to find the most powerful practices that teachers can use to support children’s oral language development. Then we visited early childhood services across Aotearoa New Zealand and gathered examples of how teachers bring these evidence-based practices to life.

This part of the report provides practical guidance for teachers to reflect on and build their practice. Each practice area is unpacked into key practices, with real-life examples of what we saw and heard in early childhood services. We encourage teachers to use the examples of practice to help them consider how they can apply these in their own service.

Overview of this section

This section sets out:

- how we found out about good practice

- five key practice areas.

1) How we found out about good practice

We looked at the evidence base, talked to early childhood services and experts

ERO looked at good practice in supporting oral language in Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood services and classrooms.

We took a deep dive into the literature on good practice for supporting oral language development. This covered both the national and international literature base, and then we checked our understandings with Aotearoa New Zealand experts.

In our fieldwork, we asked teachers about the practical ways that they bring evidence-based oral language practices to life in their early childhood service. We wanted to know about the particular strategies that have worked well in their experience. You can find their ideas in the ‘real-life examples’ boxes throughout this chapter of the report.

|

Which teachers will find these practices useful? |

|

This chapter of the report is focused on early childhood teaching practice – we draw from evidence and fieldwork around teaching and learning for children aged 0-6 years old in early learning contexts. However, new entrant teachers, and other school teachers who work with students within Level 1 of the New Zealand Curriculum, may also find some of the practices outlined in this chapter useful for their practice. |

2) Five key practice areas

Practice areas are ways that teachers can actively support children’s oral language development in early childhood education. These are drawn from the established evidence base.

We have broken down each of the five practice areas into specific ‘key practices’ that make the most difference for children. These are illustrated by real-life stories, strategies, insights, and ideas from early childhood services, including education and care, home-based early childhood services, and kindergartens from rural areas, small towns, and cities in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The five practice areas are:

|

Practice area 1 |

Teaching new words and how to use them This practice area includes intentionally using words to build a child’s understanding of words (their receptive vocabulary) and encouraging them to use and apply words in the right context (expressive vocabulary). |

|

Practice area 2 |

Modelling how words make sentences This practice area includes intentionally using language to show how words are put together to make sentences (grammar) and providing opportunities for children to use this in their own speech. |

|

Practice area 3 |

Reading interactively with children This practice area includes encouraging children to be active participants during book-reading. Teachers use prompts to encourage interactions between children and the person reading the book. |

|

Practice area 4 |

Using conversations to extend language This practice area includes intentionally using language to engage children in activities that are challenging for them. It encourages them to hear and use language to understand and share ideas, as well as reason with others. |

|

Practice area 5 |

Developing positive social communication This practice area includes providing opportunities for children to learn social norms and rules of communication – both verbal and non-verbal – so they can change the words they use, how quietly/loudly they speak, and how they position themselves when they listen and communicate with others. |

Oral language is foundational for children’s ongoing learning, through and beyond their early years. ERO reviewed international and local evidence to find the most powerful practices that teachers can use to support children’s oral language development. Then we visited early childhood services across Aotearoa New Zealand and gathered examples of how teachers bring these evidence-based practices to life.

This part of the report provides practical guidance for teachers to reflect on and build their practice. Each practice area is unpacked into key practices, with real-life examples of what we saw and heard in early childhood services. We encourage teachers to use the examples of practice to help them consider how they can apply these in their own service.

Overview of this section

This section sets out:

- how we found out about good practice

- five key practice areas.

1) How we found out about good practice

We looked at the evidence base, talked to early childhood services and experts

ERO looked at good practice in supporting oral language in Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood services and classrooms.

We took a deep dive into the literature on good practice for supporting oral language development. This covered both the national and international literature base, and then we checked our understandings with Aotearoa New Zealand experts.

In our fieldwork, we asked teachers about the practical ways that they bring evidence-based oral language practices to life in their early childhood service. We wanted to know about the particular strategies that have worked well in their experience. You can find their ideas in the ‘real-life examples’ boxes throughout this chapter of the report.

|

Which teachers will find these practices useful? |

|

This chapter of the report is focused on early childhood teaching practice – we draw from evidence and fieldwork around teaching and learning for children aged 0-6 years old in early learning contexts. However, new entrant teachers, and other school teachers who work with students within Level 1 of the New Zealand Curriculum, may also find some of the practices outlined in this chapter useful for their practice. |

2) Five key practice areas

Practice areas are ways that teachers can actively support children’s oral language development in early childhood education. These are drawn from the established evidence base.

We have broken down each of the five practice areas into specific ‘key practices’ that make the most difference for children. These are illustrated by real-life stories, strategies, insights, and ideas from early childhood services, including education and care, home-based early childhood services, and kindergartens from rural areas, small towns, and cities in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The five practice areas are:

|

Practice area 1 |

Teaching new words and how to use them This practice area includes intentionally using words to build a child’s understanding of words (their receptive vocabulary) and encouraging them to use and apply words in the right context (expressive vocabulary). |

|

Practice area 2 |

Modelling how words make sentences This practice area includes intentionally using language to show how words are put together to make sentences (grammar) and providing opportunities for children to use this in their own speech. |

|

Practice area 3 |

Reading interactively with children This practice area includes encouraging children to be active participants during book-reading. Teachers use prompts to encourage interactions between children and the person reading the book. |

|

Practice area 4 |

Using conversations to extend language This practice area includes intentionally using language to engage children in activities that are challenging for them. It encourages them to hear and use language to understand and share ideas, as well as reason with others. |

|

Practice area 5 |

Developing positive social communication This practice area includes providing opportunities for children to learn social norms and rules of communication – both verbal and non-verbal – so they can change the words they use, how quietly/loudly they speak, and how they position themselves when they listen and communicate with others. |

Practice area 1: Teaching new words and how to use them

This practice area is about teaching and modelling a wide range of words and their meanings to children.

When this is going well, teachers use a range of strategies to build children’s vocabulary, including naming, labelling, explaining, showing, repetition, and extending.

In this section, we set out why teaching and modelling new words is so important for supporting children’s oral language development. We also offer practical guidance on how teachers can build this area of their own practice.

Overview of this section

This part of the report sets out useful information about teaching new words and how to use them. It includes:

- what this practice area is

- why this is important

- what good practice looks like in real life

- a good practice example

- reflective questions for teachers.

1) What is this practice area?

This practice area is about deliberately teaching and modelling words to children through everyday interactions. This includes intentionally using words to build a child’s understanding of words (their ‘receptive vocabulary’) and encouraging them to use and apply words in the right context (‘expressive vocabulary’). To support children, teachers use strategies like naming, labelling, explaining, showing, repetition, and extending.

2) Why is this important?

Adults teaching and modelling different words for children is necessary for children to be able build and use a larger vocabulary themselves. This means children are increasingly able to comment on and describe things around them, interpret their world, and use more specific words (rather than general terms). Repeatedly naming and labelling the things children take an interest in helps them understand new words and store them in their memory. It also helps children understand that words can mean different things in different contexts.

3) What does good practice look like in real life?

The key evidence-based practices that we focus on are:

|

a) Naming |

|

b) Labelling |

|

c) Explaining |

|

d) Showing |

|

e) Repeating |

|

f) Extending |

As part of this study, we talked to teachers and service leaders about strategies that have worked well in their experience. We’ve collected their ideas and strategies here. It is important to think carefully about which of these will be the right fit for the unique context and community of each early childhood service – no strategy is one-size-fits-all.

a) Naming

This key practice involves supporting children to use the words for objects, people, and ideas in their environment. Teachers do this by tuning in to the things that children are experiencing or gesturing towards, so they can provide children with the right words to match what they see, play with, and think about.

For example, ‘ball’, ‘cat’, or ‘funny’. Teachers might use a ‘sportscasting’ strategy with infants and non-speaking children, where they narrate activities and describe things and events in the child’s view.

Teachers can also support multilingual children by affirming their use of home language words to name things, and then explaining what the word is in English, te reo Māori, or relevant Pacific or other languages that are used at the service. This privileges children’s capabilities as well as growing their word bank in the language(s) used most at the service.

“If it's a play-based learning environment, they get used to working with other children and they hear other vocabulary. So that's a gifting of vocabulary and practising their oral language skills.” (Teacher)

“We expand their emotions and identify key words that they can use to express themselves.” (Teacher)

Real-life strategies

|

We heard from teachers and service leaders that the following strategies work well |

|

Pointing at objects while naming them. Teachers shared how they would support children to name objects within ‘serve and return’ interactions, pointing to clarify what they are naming and “making sure that we give the vocabulary to what the children are trying to express.” (Teacher) |

|

Naming feelings and emotions. We heard that during conflict resolution conversations, teachers would name and repeat the feelings involved for the children, supporting them to build their vocabulary in a key area of their social learning. |

b) Labelling

This key practice involves using words to identify objects, people, and ideas across different mediums – such as relating something learnt from a screen to something seen in real life, or pointing to something in the ECE environment that is also being labelled in a story book.

Real-life strategies

|

We heard from teachers and service leaders that the following strategies work well |

|

Talking about what’s in the environment during daily activities with children. We saw teachers intentionally use care routines and mealtimes as opportunities to label things in the child’s view and talk about how they relate to other contexts. |

|

Modelling correct words after children make errors. Teachers told us how they support children to use a more appropriate word when they made a labelling error. Teachers emphasise the correct word when they reply to children – for example, “That’s right, you’re going to the library this afternoon”. |

c) Explaining

This key practice involves explaining the meanings of words to help children express ideas. Children benefit from teachers clarifying and unpacking words to gain a deeper understanding of new vocabulary.

“They can generally talk about it. Even if they can't give you specific names, they can tell you what it looks like or feels like.” (Teacher)

“We see a change in our playground behaviours. We've seen a change in children's wellbeing. They're actually expressing their feelings and needs…[they’re] actually able to articulate and feel okay about going and articulating to people.” (Leader)

Real-life strategies

|

We heard from teachers and service leaders that the following strategies work well |

|

Making it a habit to explain the meaning of new words. When teachers describe new words to children, it helps children to not only know a word, but also know how to use it. “They’re then using that vocab that they’ve heard, but they understand the vocab because we’ve explained it – we’ve broken it down. And then they might be using it in different tenses.” (Teacher) |

|

Using different words to explain the same concept or idea. Teachers shared that through such modelling, they’ve noticed children become more articulate because they’ve heard multiple ways to express a concept or idea. |

d) Showing

This key practice involves being clear about the mouth and tongue movements used when saying particular words, to help children get used to the sound as well as the feeling of saying the word. Teachers might say parts of new words extra clearly, loudly, or slowly, or talk with children about what the mouth movements look like or feel like. However, teachers should be cautious about over-exaggerating their mouth movements, as this can distort sounds.

Real-life strategies

|

We heard from teachers and service leaders that the following strategies work well |

|

Focusing on speech sounds that tend to be trickier. We heard that teachers occasionally emphasise sounds or parts of words, to prompt discussion with children. “You can pick up how they might pronounce certain things, like the ‘th’ is really hard. So, we really stick our tongues out for that one.” (Teacher) |

|

Pointing towards the mouth when saying a new word. We saw teachers gesture towards the shape their mouth was making when introducing new vocabulary. This draws the children’s attention, and they imitate the movement. |

e) Repeating

This key practice involves intentionally repeating certain words to help children gain a deeper understanding of the meaning of a word, and how the word is used in context.

“Always repeat the words as well, and what you want them to do.” (Teacher)

Real-life strategies

|

We heard from teachers and service leaders that the following strategies work well |

|

Using call-and-response to get children speaking. We saw teachers say a word, then prompt children to repeat it together. This can be done with individuals or groups of children. |

|

Encouraging children to repeat new words. This can help children consolidate new vocabulary. “I said, ‘Well, you can use your words. How could you say it?’ So, if she hasn’t got the word, I give her the words and I let her repeat the words.” (Teacher) |

f) Extending

This key practice involves adding extra words, for example, adjectives or adverbs, to descriptions (e.g., ‘big red ball’). This helps children to extend and expand their knowledge, by giving them the words to do so. Teachers can also encourage sustained shared thinking by responding to questions that children ask and helping them to articulate and extend their ideas by modelling new vocabulary. For infants and children who are not yet speaking, ‘serve and return’ interactions which involve teachers responding to gestures, eye contact etc., with spoken words, are another useful form of extending.

Real-life strategies

|

We heard from teachers and service leaders that the following strategies work well |

|

Actively listening to children and adding on to what they say. For example, we saw teachers verbally engaging with children as they arrive in the morning. When children share about their morning or family experiences, teachers build on their words, relating to what they already know about the children and their families. |

|